Stagflation, Again?

What Makes Today the Same As—and Different From—the 1970s

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 10,800 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

Programming Note: Apricitas has a new official website! You can now visit via apricitas.io, but all old links using apricitas.substack.com should still work!

You will not notice any change to email or in-app content deliveries, I just decided it was time to move to an official website with a unique domain name.

Humans are narrative-driven animals; we evolved to synthesize information through sharing and re-sharing of stories. That applies to economics as well—the first instinct for many commentators is to dust off the history books in order to explain today’s economics. Think tanks compared 2020’s jump in unemployment to the Great Depression, some academics compared the surge in wages last year to the rise in workers’ fortunes in the aftermath of the Bubonic plague, and Biden’s White House Council of Economic Advisors compared the original surge of inflation to the immediate post-WWII period.

With energy prices rising, inflation at a 40-year high, and real output wavering, the go-to macroeconomic comparison for today’s situation is now the “stagflation” era of the 1970s.

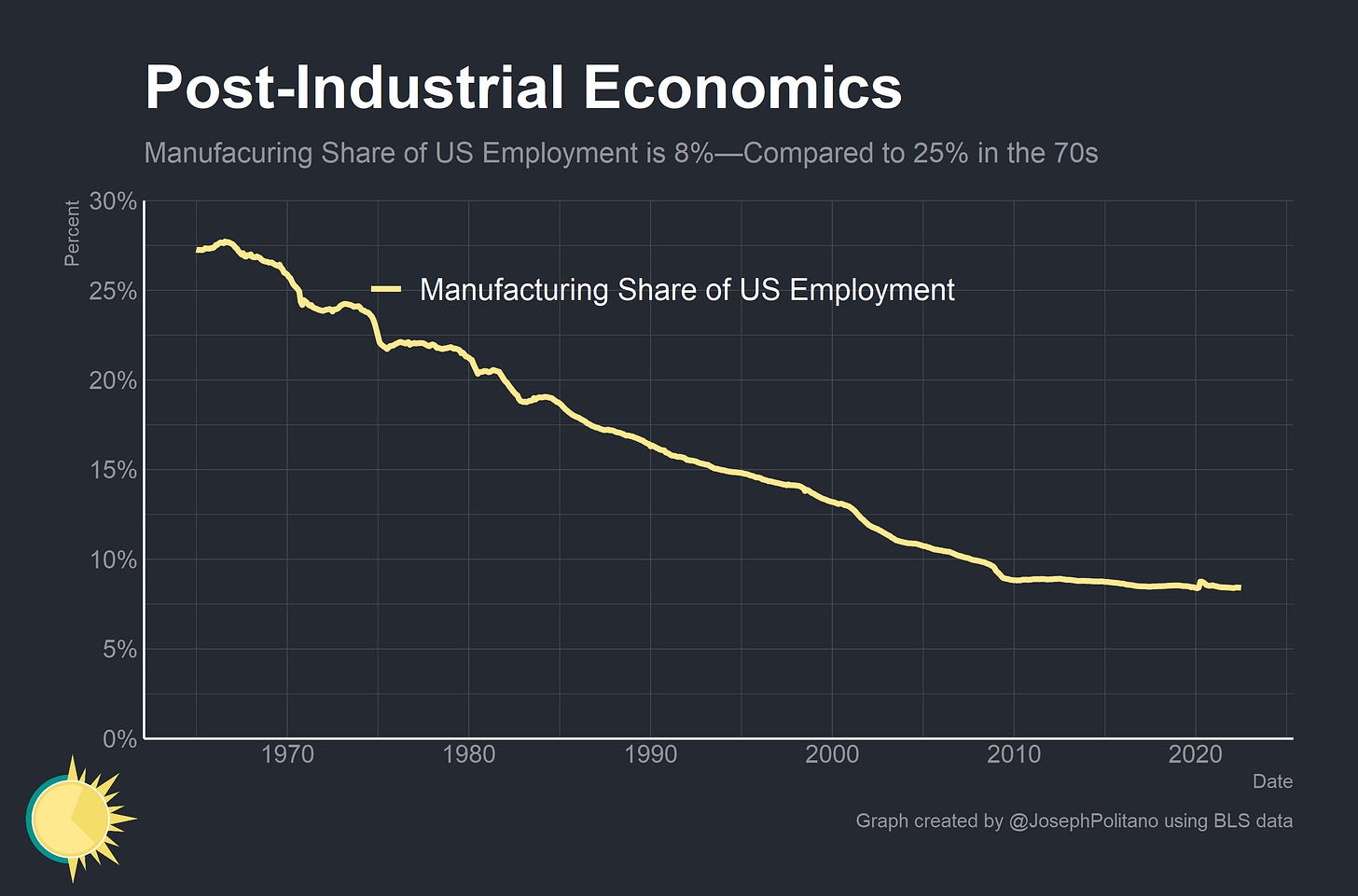

But historical comparisons often obfuscate as much as they reveal. The narratives we form about the past often paper over or ignore some of the more complicated facts, and thinking the future will continually mimic the past is possibly the most common trap in forecasting. The economy of the 1970s was different from the economy of today in important ways—the size of today’s energy shock is smaller than the OPEC embargo, America is a bigger producer of energy than in the past, energy-dependent manufacturing makes up a smaller share of US employment, aggregate employment growth is significantly lower than during the 1970s, the psychology of high inflation is not currently embedded in consumer expectations—and that’s only scratching the surface.

That ‘70s Economy

Perhaps the most immediate difference between today’s economy and the 70s’ is the size and scope of the energy crises. When OPEC imposed an embargo on the US and other countries in response to their support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War, domestic oil prices spiked and American consumption of fossil fuels sank dramatically. Crude oil prices quadrupled during the 1973-74 embargo, though consumer prices were controlled through enforced rationing. The 1979 Iranian revolution and ensuing Iran-Iraq war brought oil prices to more than 10x their 1970 levels by the end of the decade—by contrast, the price of oil is currently “only” about 50% higher than its pre-COVID level and the hit to consumption has been much smaller than during the 1970s.

The other important difference is that the US is more “energy independent” than during the 1970s—the US is now a net exporter of total crude oil plus petroleum products alongside being a net exporter of natural gas. “Energy independence” is probably marginally overrated as a concept—energy is traded in global markets so prices of domestic energy commodities (especially oil, but to a lesser extent natural gas) are still subject to fluctuations in global supply in demand even if most of US consumption is physically sourced domestically. What is important is that the shale revolution has fundamentally reshaped the US’s ability to respond to price shocks in energy markets—during the 1970s, domestic US production was basically at capacity and could not rapidly make up for declines in OPEC production. Today, though domestic producers are responding slower than in the 2010s, they are still ramping up output much faster than in the 1970s. Though it is cold comfort to Americans dealing with higher energy prices, it is also true that domestic US producers are now better able to benefit from exporting oil and natural gas abroad.

‘Stag’ Hunting

Irrespective of size, today’s energy crisis is affecting the US economy in vastly different ways than the energy crisis of the 1970s. As a high-income post-industrial economy, manufacturing makes up a much smaller share of US employment today (about 8%) than it did in the 1970s (about 20-25%). That’s important because manufacturing output is much more directly dependent on energy consumption than, say, education, healthcare, or food service output. Jumps in energy prices therefore directly negatively affect employment in manufacturing more so than many other sectors, so an economy with more manufacturing employment will be more vulnerable to energy shocks. For good or ill, the US is no longer an economy largely dependent on manufacturing employment—though growing employment sectors like transportation and warehousing are likely to have similar issues with rising energy prices.

However, there are more important differences between the labor market of the 1970s and today. For one, the 1970s were characterized by extremely large working age population growth as the Baby Boomer generation came of age—in direct contrast to today’s essentially zero working age population growth. That’s important because high population growth and younger average ages are thought to drive higher “equilibrium” real interest rates—the interest rate necessary to stabilize inflation. Rising population growth drives higher real output growth directly through an increase in the number of workers while also accelerating the demands for capacity investment to house, clothe, feed, and transport these new adults. Younger people also tend to have higher discount rates—that is, they value current assets higher compared to future assets—all of which push “equilibrium” real interest rates higher. Today’s ageing population, extremely low working age-population growth, low real output growth, and high inequality all tend to push real rates down—hence why rough estimates of 10-year real interest rates were at 7.5% in the early 1980s and are at less than 1% today.

It was not just the working-age population that grew, either. The 1970s saw the fastest increase in employment levels in modern American history as larger shares of women entered the workforce alongside the rapidly growing total working-age population. Less than 80 million people were employed in the US at the beginning of the 1970s and nearly 100 million people were employed at the start of the 1980s. The prime-age (25-54) employment-population ratio increased 5% over the decade, with the female prime-age employment-population ratio increasing a full 10%. Unemployment remained high throughout the period—stagflation, after all, was named for the then-unprecedented conundrum of rising inflation and rising unemployment—but that high unemployment is probably best understood as employment levels growing at an exceptional rate that still was not enough to keep up.

Indeed, the “stagflation” moniker has masked a lot of the real growth that occurred in the 1970s. Real GDP, GDP-per capita, income, and consumption all increased at regular or higher-than-regular levels throughout the decade despite the oil shocks, high unemployment, and recessions. Industrial production increased 30%, the US built massive numbers of homes, and real private fixed investment growth was high.

The true driver of the 1970s inflation was massive increases in total nominal spending even in excess of the regular-to-high real output growth. Nominal spending per capita increased at a 10% or higher rate throughout large chunks of the 70s—a number simply too large to avoid high inflation even despite robust real economic growth. Monetary policymakers in the 1970s persistently underestimated the interest rates necessary to bring spending and inflation down, leading to nominal growth levels that were extremely high alongside the oil shocks that dominate the public imagination.

That rising inflation manifested as persistent increases in consumer, business, and worker expectations of inflation throughout the economy. That’s a critical part of the narrative of the 1970s; inflation expectations became unanchored as realized inflation remained high for years until Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker induced a recession to bring both inflation and inflation expectations down.

I’ll have more to say on inflation expectations in a future post, but suffice to say that long-term inflation expectations were higher in the 1970s and individuals had more ability to act on those expectations in ways that entrenched inflation. Unionization rates were much higher in the 70s, allowing workers to bargain aggressively for higher wages and cost-of-living adjustments. Households increasingly bought durable goods out of fear that prices would increase further—which helped buoy inflation by increasing demand. Expanding mortgage credit access allowed households to bid up home prices, further fueling spending growth. Combined, this made inflationary impulses much more entrenched—and much harder to get rid of.

Conclusions

This is, to say the least, only scratching the surface of the differences between today’s economy and the 1970s. The 70s had preexisting fiscal impulses from the expansion of Great Society programs and the money-and-labor drain from the Vietnam war. Wealth inequality was lower, pushing up real interest rates. Global trade was less prevalent, keeping output lower while putting a larger strain on domestic manufacturers to manage capital formation—but avoiding some of the extreme complexities of modern supply chains. Central banks in the US and across the globe were much less politically independent of elected officials.

But perhaps the largest difference is in the wealth of economic knowledge and data modern society has access to. The monetary system of the 1970s was practically brand new—the US ending the dollar’s international gold convertibility severed the last link to the old ways of international finance, and central bankers were forced to plot a new course with no new compass. When their old theories failed them, they struggled to cope. Now policymakers have instant access to orders of magnitude more live data and decades of research into the modern macroeconomy. Call it bad forecasting, panicked decision-making, or data-driven policy, but faced with a rolling series of unprecedented economic situations governments and central banks have pivoted faster than ever before. It is the persistence of inflation throughout the 1970s that made the decade truly unique, and while history is still being written the chances of a decade-long inflationary policy mistake seem much lower.

While I understand the idea that a policy mistake seems much less likely given the seeming advances in understanding and data availability, I fear that by virtue of the fact that the Fed, and basically every major central bank, is focused on backward looking data, the chances are actually still quite high. to me the question is just how long will they continue along the poisoned path.

I hope you are correct, I fear you are not.

Thanks for a very good summary

With regard to the impact of oil prices, isn't a barrel of crude oil delivered to the refinery less expensive from a domestic source than a barrel shipped from the mid east or even South America? We're been told that shipping costs skyrocketed when this inflationary cycle started?.