Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 24,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

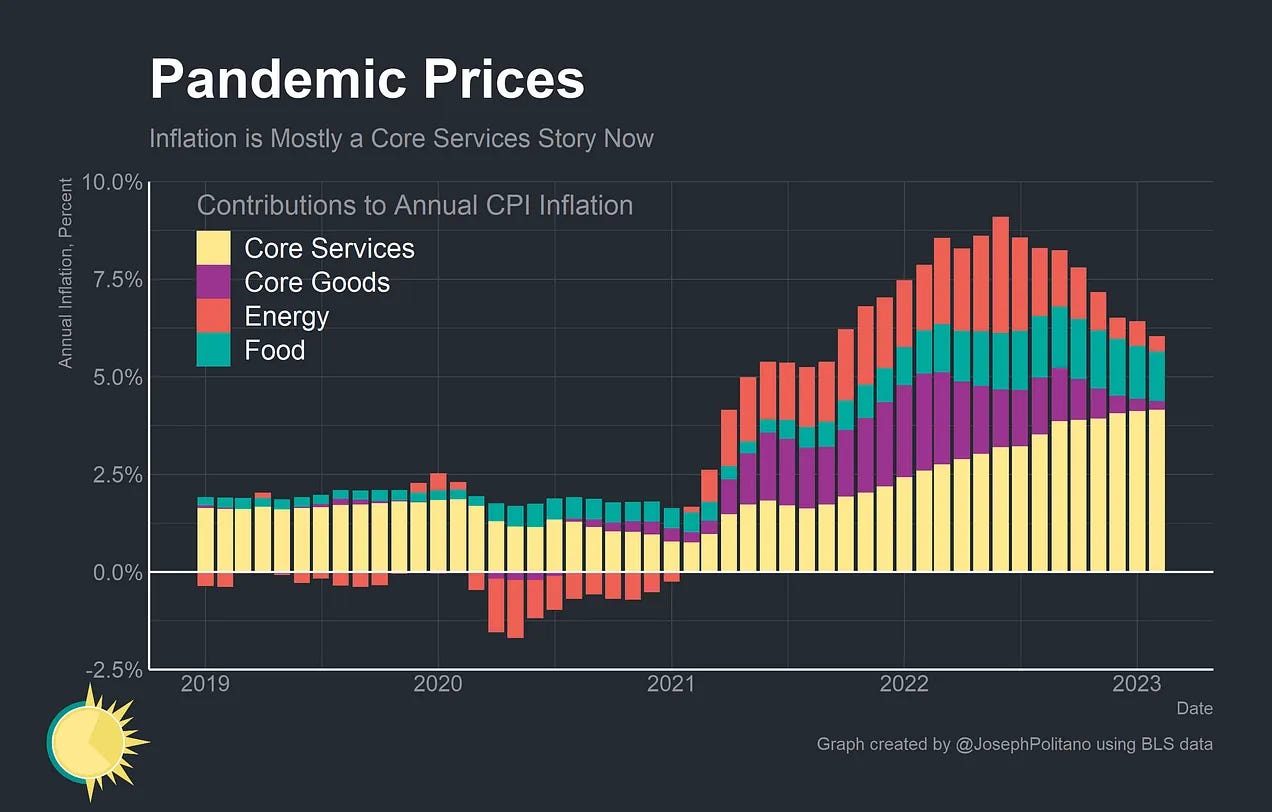

The outright majority of today’s US inflation comes from demand-side pressures. There is too much money chasing too few goods, and cyclical inflation in housing and labor-intensive core services represents a serious problem that the Federal Reserve—and central banks across the world—are looking to address. Plainly, global monetary policymakers (and global financial markets) were operating in highly uncertain times and systematically underestimated the underlying strength of nominal growth and the interest rates necessary to keep inflation on target. Tighter monetary policy is now clearly slowing the economy and making progress in decreasing inflation, especially when you account for the lags associated with measurements of housing prices, but core price growth is still significantly above target.

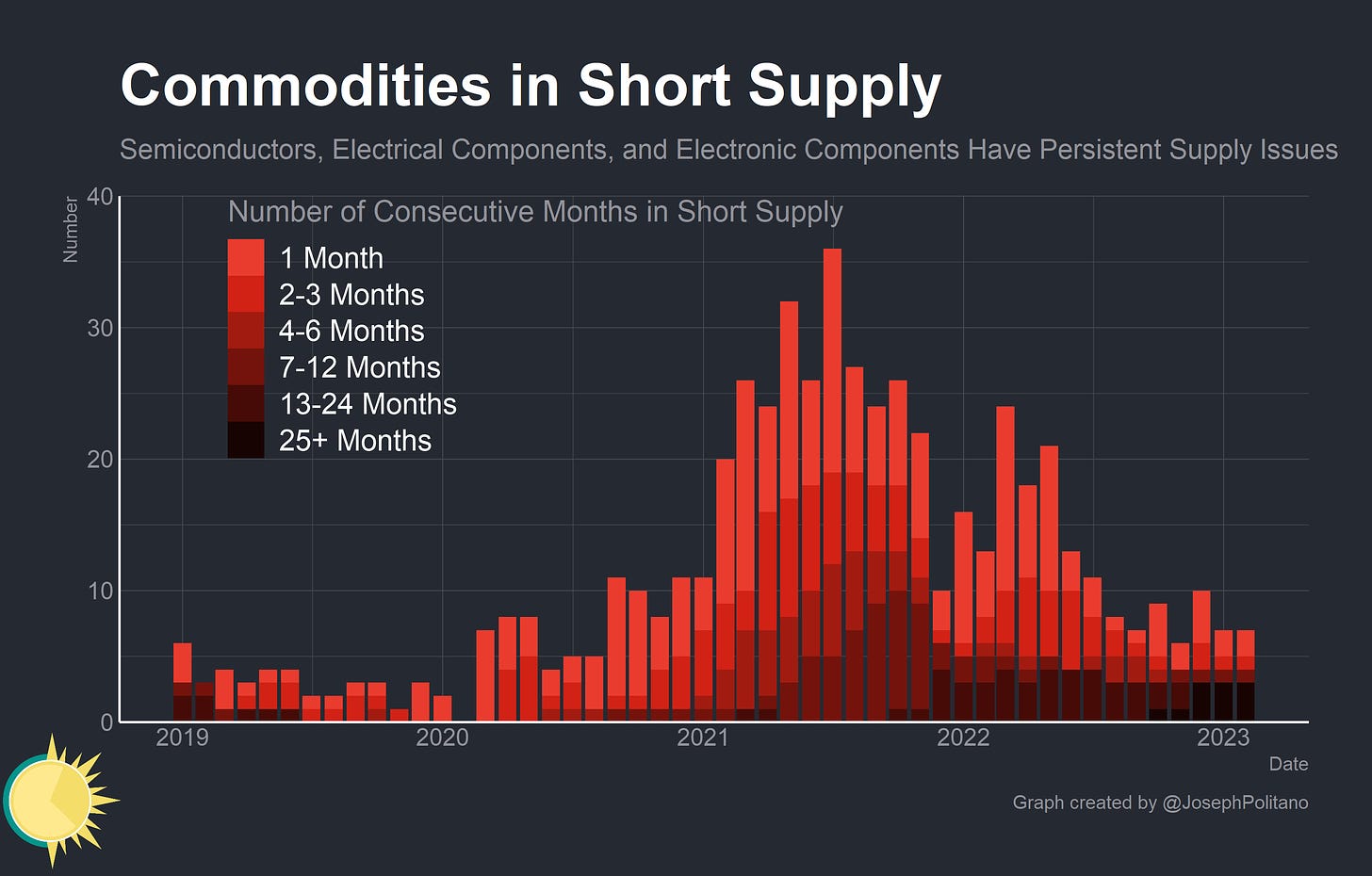

However, I think perhaps people have misunderstood these facts to mean “supply-side inflation doesn’t matter anymore” or “supply-side inflation never mattered.” Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was just over a year ago, and its net effects on US inflation are clearly still positive, especially with regard to food prices. There are still practically unprecedented dislocations in global manufacturing supply chains that are pushing up inflation—with lead times, input shortages, logistics constraints, and unfilled orders at elevated levels. The pandemic has likely killed millions of people in China over the last 3-4 months as the country wound down its COVID-Zero policies while in the US, the pandemic caused the number of American workers out thanks to childcare issues to reach a record high this fall. Large amounts of manufacturers in key industries still cite supply chain constraints as more binding than before the pandemic, especially in the case of semiconductors and other electronic components. All those dislocations are a large part of the reason why US real GDP growth was so weak, especially at the beginning of 2022, and why inflation has been such a persistent and global phenomenon.

Critically, a lot of those supply shocks have been structural rather than temporary. The idea that inflation would be transitory rested on the assumption that 1) inflation primarily reflected disruptions to supply chains and 2) those disruptions would quickly fade away as the economy recovered, without the need for interest rate increases. The first point became false as inflation broadened from select food, goods, and energy to the vast majority of categories including housing, healthcare, personal services, and more. But that second point also became false as supply chain issues persisted. Several key items—electrical components, electronic components, and semiconductors—have been listed as in short supply by US manufacturers every single month for more than two years consecutively. These physical capacity constraints have been much more widespread and binding than in many past inflationary episodes, and the fact that supply chains are not yet close to something resembling a “pre-pandemic equilibrium” despite significant price increases points to their continued upward pressure on inflation.

Taking an honest look at today’s economy and the factors driving American inflation requires taking into account supply-side issues—while also acknowledging that those components are no longer the primary drivers of price increases.

What Does it Mean When Supply Chains Are Stuck?

In practice, equilibrium is more of a process than a state of being in economics—all businesses could theoretically adjust prices day-by-day and moment-by-moment the way commodities like gasoline operate on financial markets—but instead they make a mix of choices on prices, inventories, delivery times, quality, size, and much more to try to balance market demand with their production capabilities. In most cases, a constantly-adjusting-price-scheme would be undesirable because customers (many of whom are other businesses) place a premium on certainty, because adjusting prices constantly usually introduces more administrative hurdles than adjusting inventory/production, and because one company is often selling several complementary or related products and so takes a more comprehensive pricing strategy. That’s how you end up in a situation where even consumer-facing businesses are willing to endure ongoing shortages rather than jack up prices—two years after its release, it can still be difficult to find a new PlayStation 5 to buy.

That’s all to say that businesses tend to adjust delivery times, inventories, and more alongside adjustments to prices, and the state of nonprice adjustments can give signals to the future direction of price adjustments. With that in mind, it’s clear that nonprice indicators still show large strains in supply chains that will likely keep prices elevated in the short term. Average production material lead times—the amount of time between order placement and delivery for manufacturing inputs—remain significantly elevated above pre-pandemic norms, indicating that suppliers are still struggling to meet demand despite rapid increases in many raw material prices.

The share of American manufacturers citing materials or labor shortages also remains well above pre-pandemic levels, as does the amount struggling with logistics and transportation constraints. Critically, this does not represent firms that are simply paying more for key inputs—these are firms that are being forced to run their facilities below full capacity thanks to ongoing shortages. These constraints have eased significantly throughout 2022, and more recent data from Canada suggests they have eased further since, but still suggest ongoing supply chain issues are putting upward pressure on input prices—an idea corroborated by higher frequency qualitative survey data from the regional Federal Reserve banks.

In several key US manufacturing industries, materials shortages are still extremely acute—in the recently released data for Q4 2022, nearly 60% of American computer and electronic product manufacturers were not able to operate at full capacity thanks to materials shortages alongside nearly half of transportation equipment manufacturers (which mostly represents carmakers and aircraft manufacturers). Although some chip prices have been falling recently and areas of the semiconductor industry now look to be in a supply glut, the complexity of electronics supply chains and the wide variety of chips necessary for many products means that some components remain in short supply and the semiconductor shortage is evidently still binding for many firms.

Indeed, of the key US industries most affected by supply chain issues in 2021 and 2022 it is computers & electronics and transportation equipment manufacturing that have seen the weakest recovery so far. Chemicals, machinery, and electrical equipment have all seen more substantial improvements thanks to being less directly connected to chip shortages.

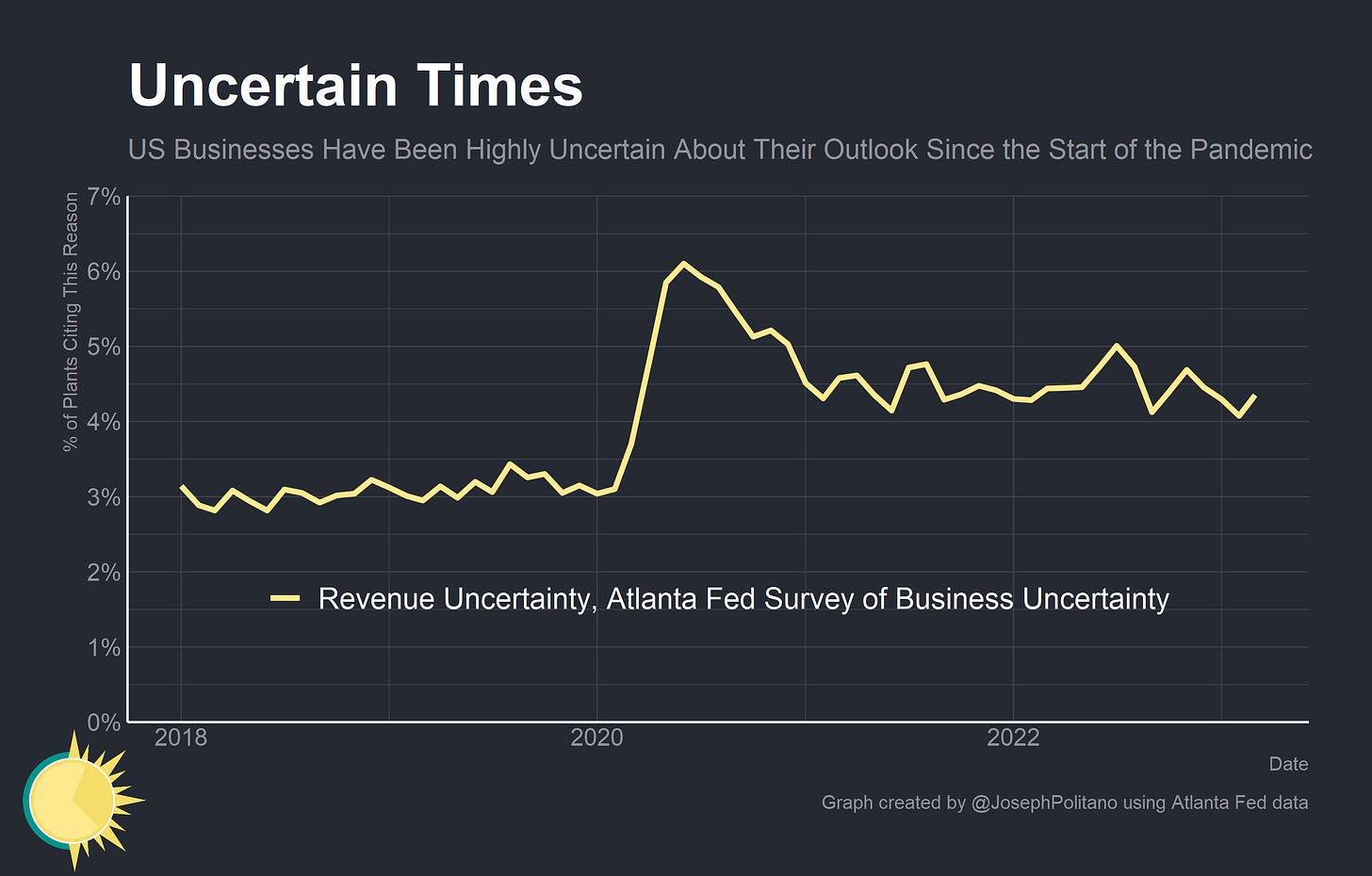

So why the ongoing structural supply shocks—and why haven’t companies been able to fix their supply chains in the three years since the pandemic began? The fundamental answer is that unprecedented things keep happening across the world (COVID, Russia's invasion, China's reopening, etc) and that many supply chain components have limited or difficult-to-spin-up capacity, but the broader point is simply that uncertainty remains highly elevated. As mentioned earlier, businesses don’t just tweak prices daily to balance output and sales, they adjust inventory, build capacity, modify production processes, manage supplier relationships, and more. In other words, businesses do a ton of forward planning—and those plans come under tremendous stress when put under the kinds of shocks the global economy has faced recently. Critically, uncertainty makes formulating accurate plans and executing them well extremely difficult—and US companies have been extremely uncertain about the future since the start of the pandemic.

But there are also ongoing efforts to increase capacity in the wake of those persistent supply shortages—in particular, construction spending by US computer, electronic, and electrical manufacturers has surged to a record high amidst strong demand and heavy investment in semiconductor manufacturing propelled by the recently-passed CHIPS Act. Construction by transportation equipment manufacturers has also picked up significantly, and American carmaking capacity has exceeded pre-pandemic levels even as output remains constrained by the semiconductor shortage.

Demand is (Still) The Bigger Problem

The bigger problem is simply that Americans continue to earn and spend a cumulative amount too large to be consistent with 2% inflation—over the last year, both personal income and outlays have grown by 8.3% and now sit well above pre-pandemic. Even if the US economy was running at full speed compared to 2019 and had no supply-side issues to speak of, it could not sustain that level of income and spending growth without inflation in the range of 4-6% per year. The key task for the Federal Reserve remains to get nominal spending back down to a more manageable level, and the key question remains whether they can do that without throwing the US economy into a recession.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.