Sure Friends Betrayed

Canada & Mexico Wanted to Anchor US "Friendshoring" Efforts. Instead, Trump's Tariffs Risk Throwing Them Into Recessions

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 58,000 people who read Apricitas!

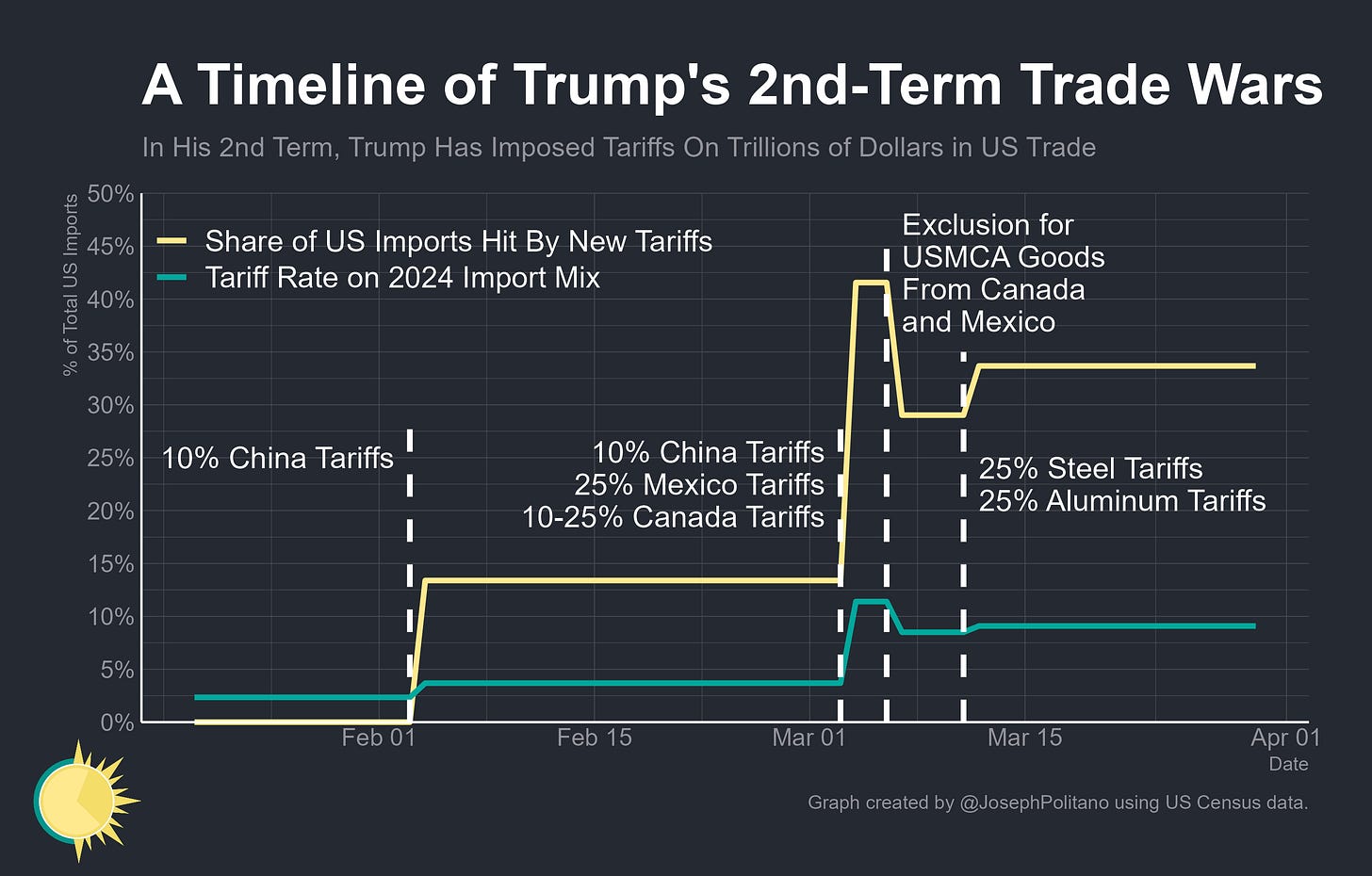

For two months now, Donald Trump has been repeatedly threatening a massive trade war against both of America’s neighbors. In early February he signed an executive order placing 25% tariffs on all goods from Mexico and Canada, but backed down before the implementation date and agreed to a one-month pause after receiving token concessions. In early March he let those tariffs come into force for a few days, only to partially backtrack by announcing the tariffs would exclude all goods imported under the USMCA trade deal’s rules of origin until early April. In the meantime, he implemented 25% tariffs on all steel and aluminum entering the United States, products where Mexico and Canada are both key sources of imports, and he continually promises universal tariffs will actually go into effect starting next week alongside a suite of tariffs on most of America’s largest trading partners. Plus, he’s continually expanding the trade war using additional actions against major Canadian and Mexican exports like the automobile tariffs signed yesterday and upcoming tariffs on lumber, agricultural products, and more.

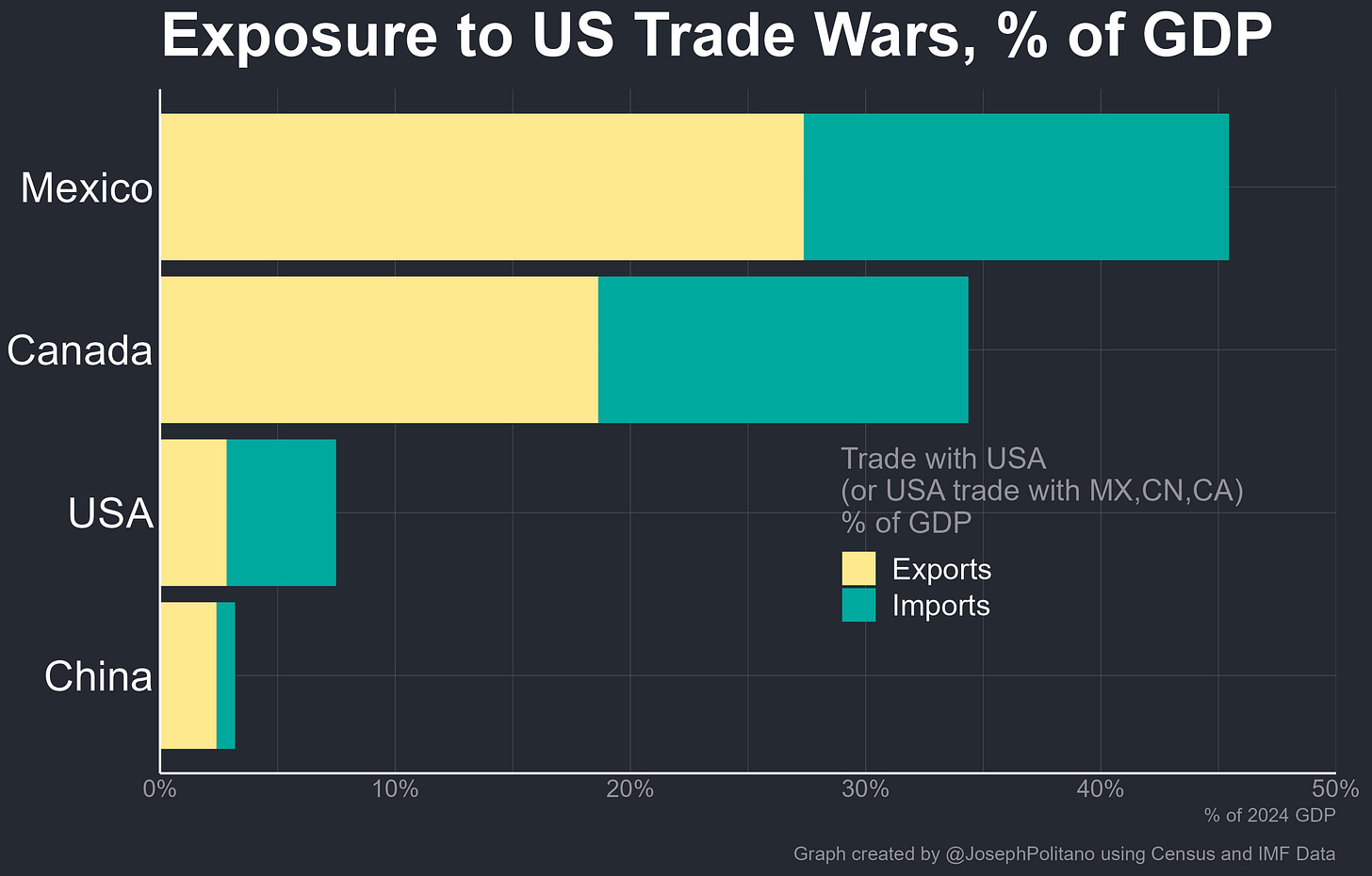

These tariffs’ economic costs will be disproportionately borne by American workers, companies, and businesses, but the US is an extremely large diversified economy with room to absorb shocks that would thoroughly devastate most other countries. By contrast, Canada and Mexico are much smaller by both population & GDP—even though the cost of the trade war is mostly absorbed by Americans, the share that falls on Canada and Mexico is larger relative to their economies. US trade with Canada and Mexico is 7% the size of its GDP, meanwhile Mexico and Canada’s trade with the US is 45% and 34% the size of their GDP, respectively, making them by far the most exposed countries to the effects of a US-led trade war. The Peterson Institute for International Economics thus estimates that the trade war would reduce Mexican and Canadian GDP by 4-5x as much as US GDP and would increase inflation by 3-4x as much. Officials at all levels of the Mexican and Canadian governments are drawing up plans to brace for a possible trade-war-driven recession.

The cruel irony is that both countries have spent the last decade-plus trying to make themselves the centerpiece of US “friend-shoring” efforts to move supply chains towards its close allies. When Trump’s first-term trade war against China erupted, it was factories in Mexico or Canada that worked to replace many Chinese-made goods. When Biden passed the Inflation Reduction Act, North American EVs and batteries could qualify for large tax credits not extended to the Europeans or Japanese. When he signed the CHIPS Act, Canada and Mexico rushed to find ways to partner on the semiconductor supply chain buildout. When the US used tariffs to functionally ban imports of Chinese EVs, it pressured Mexico and Canada to follow suit with tariffs of their own. Now, both countries are instead being treated as economic enemies, significantly worse than dozens of dictatorships where the US still has normal trade relations.

Unlike the first term, this is a Trump administration that believes in on-shoring or nothing, sees its neighbors’ manufacturing industries as undermining rather than assisting their own, and views tariffs as a means to cajole allies just as much as a means to punish enemies. Expanding the trade war like this is going to amplify its costs, undermine US growth, increase business uncertainty, hurt US allies, and make the administration’s stated goal of “strategic decoupling” from China even more difficult. If Trump continues down this path, it’ll be the death knell of the “friend-shoring” era and an incredibly costly move for economies throughout North America.

How a Trade War Could Break Mexico & Canada

Right now, Trump’s tariffs on Canadian & Mexican goods only affect steel, aluminum, and products that do not enter under the rules required for preferential treatment under the USMCA deal signed during Trump’s first term. Roughly 62% of imports from Canada and 51% of imports from Mexico didn’t enter under those zero-tariff USMCA provisions in 2024, either because baseline US tariffs were already zero in that category or because USMCA compliance was too economically or bureaucratically onerous. That means that, at most, tariffs are currently affecting roughly $257B in imports from Canada and $259B from Mexico, bringing the total amount of imports currently affected by Trump’s tariffs on Canada, China, and Mexico down to a maximum of $952B.

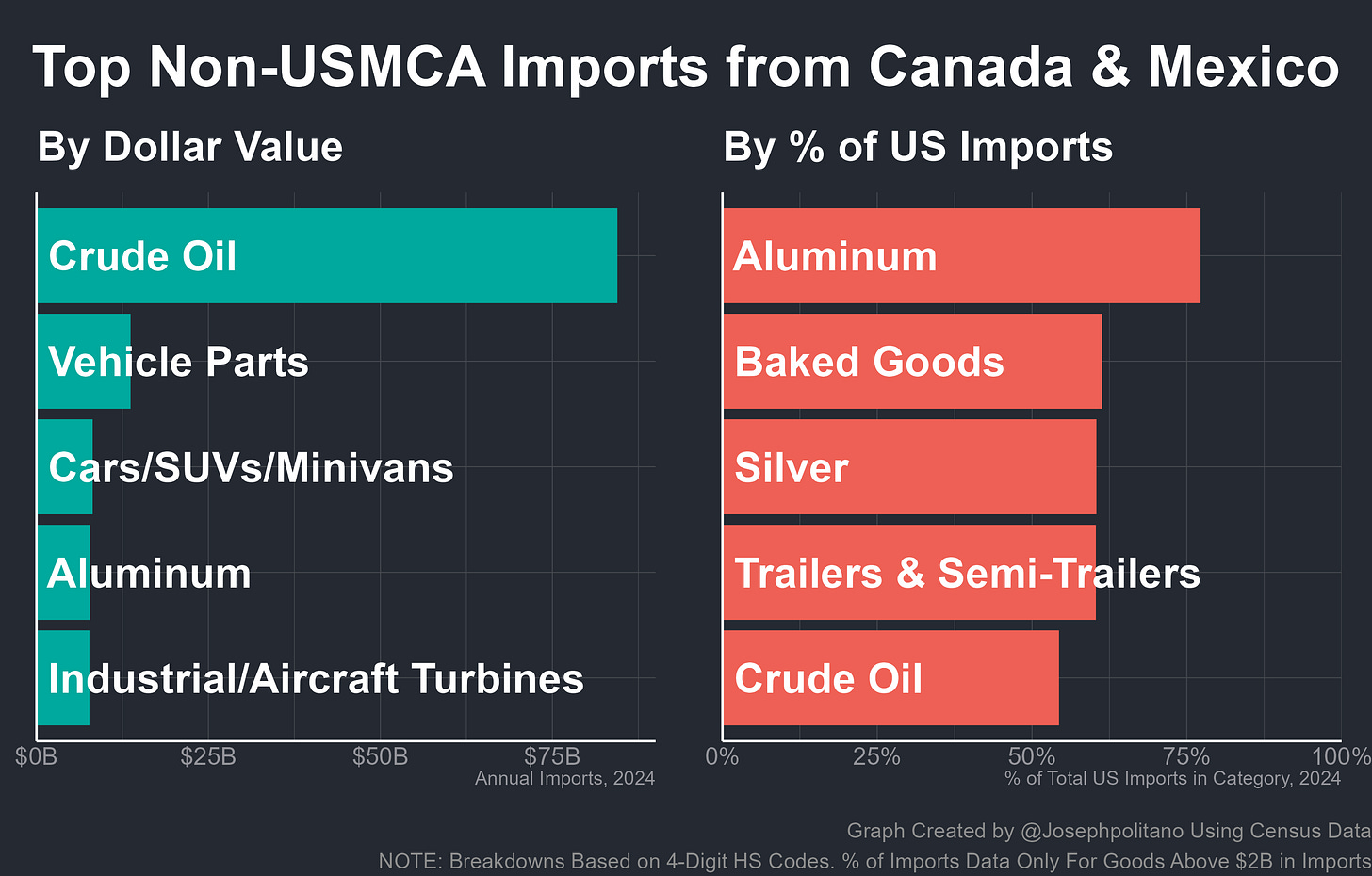

Last year, the single-largest non-USMCA-compliant import was Canadian crude oil, followed by Mexican cars & parts, Canadian aluminum, and then mostly-Canadian industrial/aircraft turbines. Various baked goods, silver, and vehicle trailers could also be hit hard. In practice, however, the large majority of those imports likely just need to fill out paperwork to become USMCA-compliant—the Mexican Secretary of Economy said that 85-90% of total exports could qualify for the exclusion while the Canadian trade minister said that “virtually all” could be eligible. Yet it remains extremely unclear precisely how much is being exempted, and those estimates might be sugar-coated given that the USMCA does not have systems built out to accept many goods or that tens of thousands of corporations would have to move quickly to get a reprieve they will ostensibly lose in only a few days.

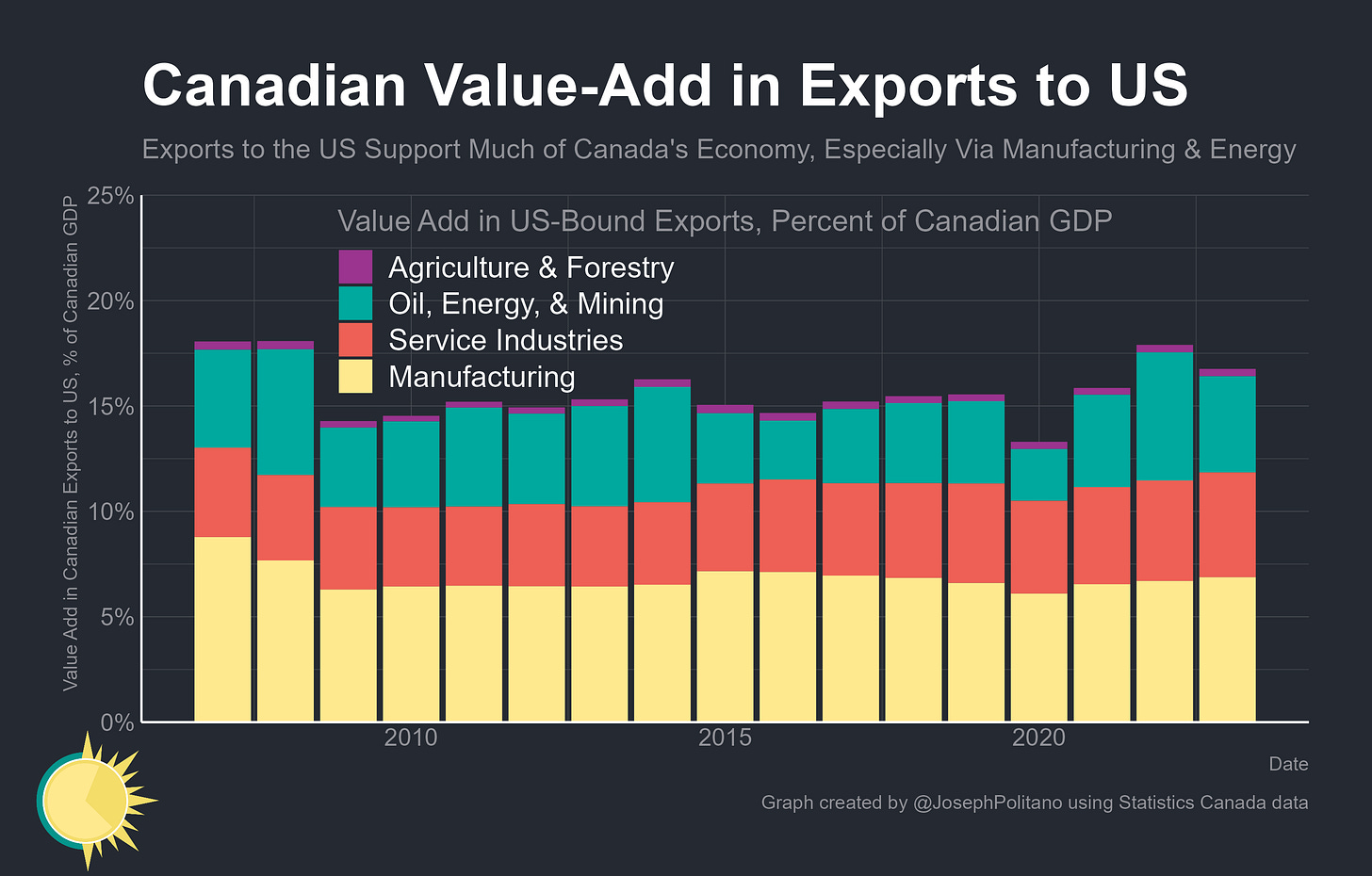

For Canada and Mexico, even these smaller tariffs are the largest trade shock since the pandemic, and the perpetual threat of universal tariffs looms extremely large. Much of the Canadian economy is directly or indirectly built around exports to the United States—as of the latest data available, Canadian value-add in US-bound exports made up roughly 17% of the country’s economy, boosted by the large southern-oriented manufacturing and energy sectors. Within manufacturing, the primary metals, motor vehicles, and wood product sectors were the three largest contributors—all three of which have or are expected to be hit with even higher additional tariffs.

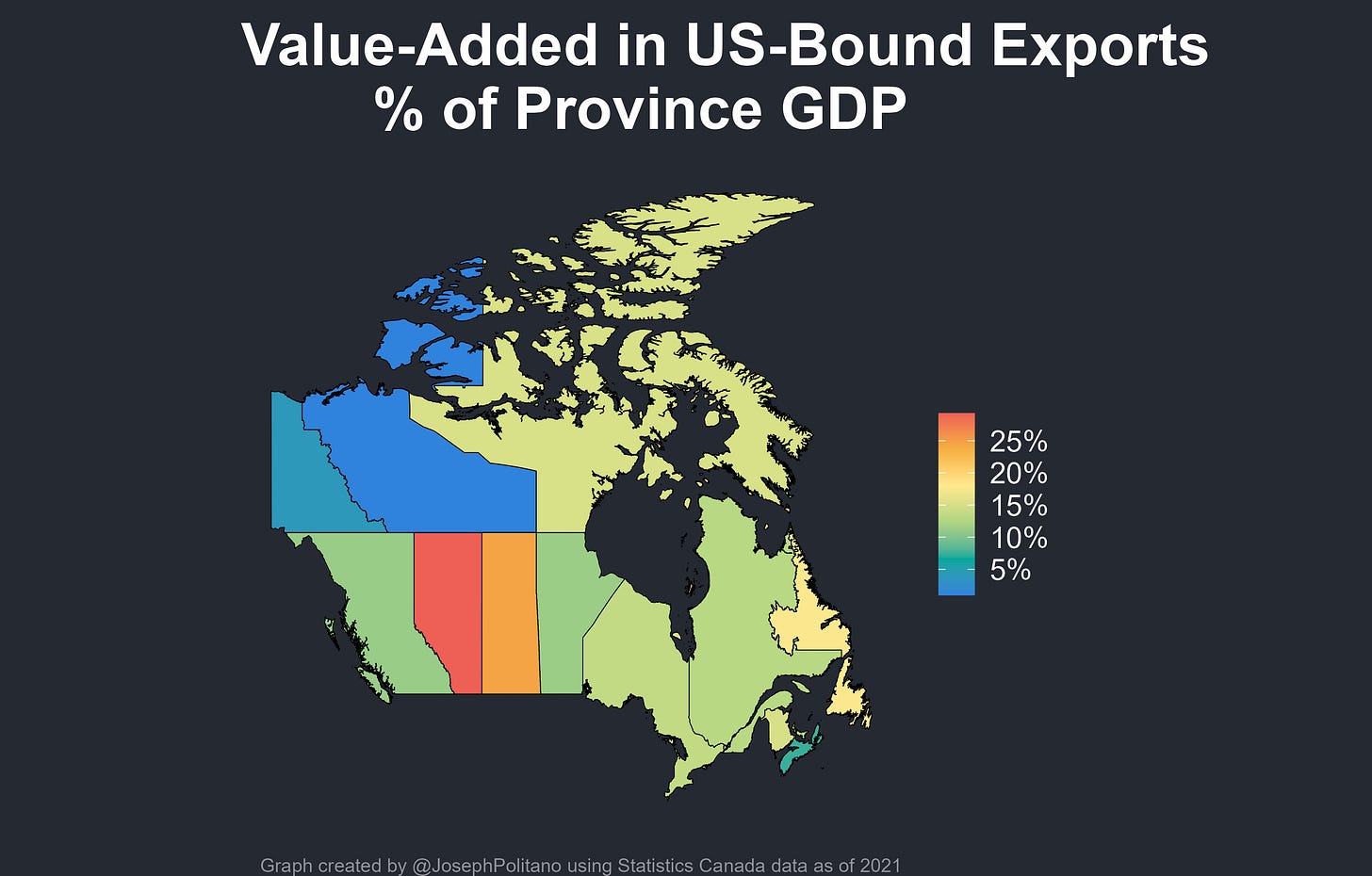

For virtually all Canadian provinces, exports to the United States rival or exceeds exports to the rest of Canada combined. As a share of GDP, the oil-producing provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan are most dependent on exports to the US, but even the largest Canadian provinces like Ontario or Quebec have much of their economy wrapped up in southbound trade. Indeed, they would almost certainly be hit harder given the lower tariff on oil exports and inflexibility of pipeline trade compared to sectors like auto manufacturing.

Even the threat of US tariffs is already having negative economic effects by amplifying fear and uncertainty. In surveys done by the Bank of Canada, Canucks are already bracing for the impact of trade tensions—consumers are trying to save more and spend less, businesses are cutting hiring and slowing investment, and both have raised their inflation expectations for the year. Employees in trade-dependent sectors like oil, gas, mining, and manufacturing are increasingly worried about losing their jobs.

However, Mexico would likely be hit even harder than Canada given that country’s economy is substantially smaller, more industrial, and more connected to the United States. Roughly one-in-six Mexican workers are in manufacturing, compared to one-in-eleven Canadian workers or one-in-twelve American workers. Plus, roughly 30% of all Mexican manufacturing employees work in export-oriented factories (aka Maquiladoras), the vast majority of which are built around shipping goods to the United States. Those workers are heavily concentrated in the auto sector, but are also spread through industries like computers, plastics, appliances, metals, and more.

Even now, the tariffs on non-USMCA-compliant goods are certainly hitting Mexico harder than Canada—while both countries exported roughly $250B to the US outside the trade deal’s rules in 2024, more of Mexico’s exports were manufactured products where all non-USMCA goods are tariffed and thus definitively can’t become eligible just by filling out paperwork. In 2024, $39B of US imports from Mexico were in these non-energy goods categories subject to tariffs compared to $10B in total imports from Canada. Those Mexican imports include $10.8B in vehicle parts, $7.4B in cars, and $1.6B in ICE engines, meaning the country’s large export-oriented auto sector has already been hardest hit even before the specific car-related tariffs kick in.

States along Mexico’s northern border are unsurprisingly going to be hit the hardest by any further trade war escalation—Chihuahua, Coahuila, and Baja California have the highest US-export-to-GDP ratio of any state in Mexico. Those northern states had also seen some of the fastest production and investment growth over the last few years as US-Mexico trade continued to grow.

No Friends Ashore

The cruel irony of Trump’s tariffs threats is that both Mexico and Canada worked hard to support US industry amidst recent “nearshoring” and “friend-shoring” pushes—including during Trump’s first term. In the modern industrial policy era, the US has undertaken multiple escalating government interventions in trade and manufacturing sectors to support domestic industry but has generally accepted that no modern country can or should go it alone. Instead, it worked to onshore key sectors like semiconductors while mostly limiting itself to the already-arduous task of partial decoupling from China. Even though neither Canada nor Mexico were the largest beneficiaries of tariff-driven “trade-diversion” away from China, they did both play massively important roles in that reorientation of supply chains.

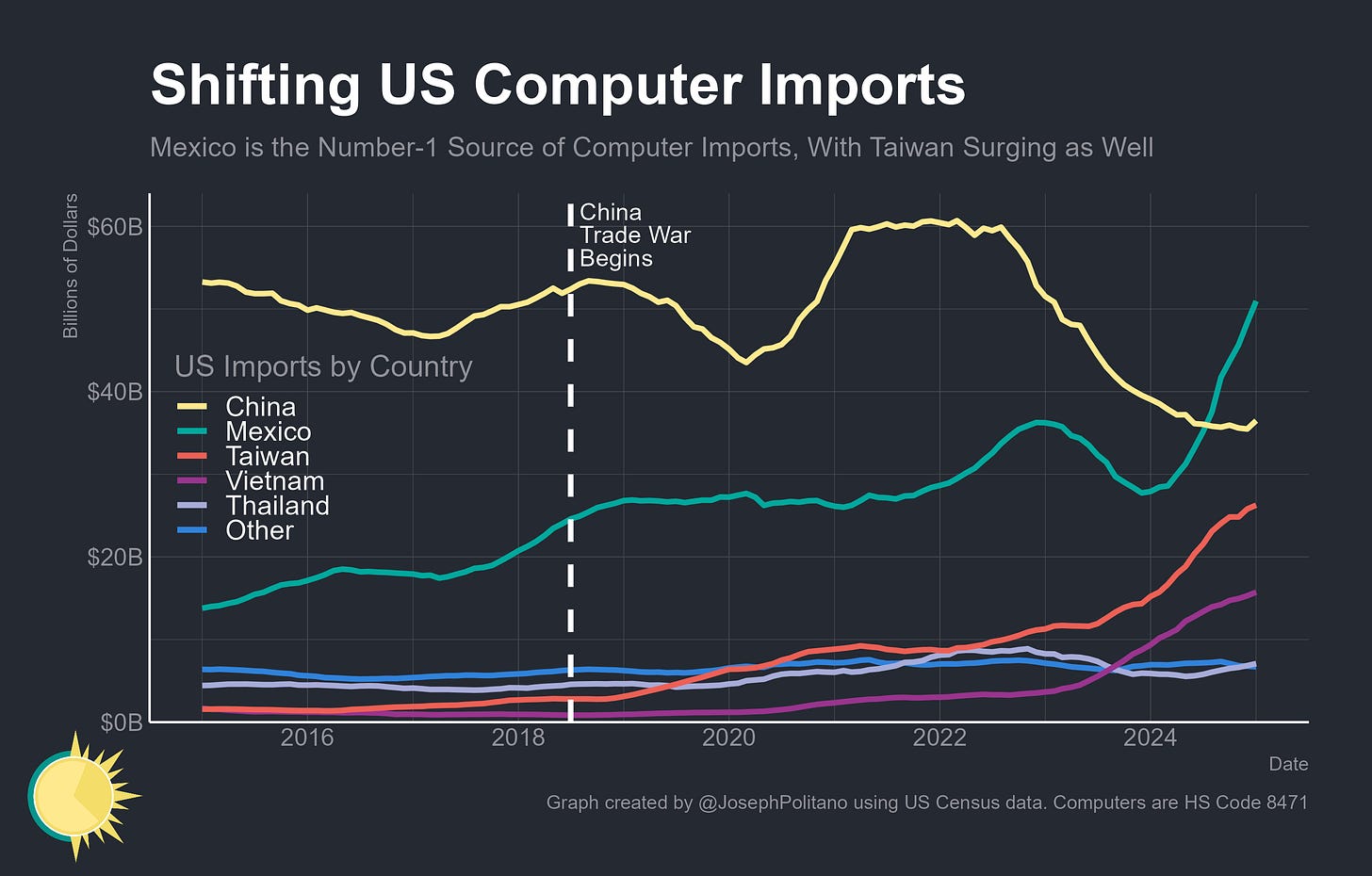

Take the computer manufacturing industry as an example—ten years ago, China was the dominant source of US computer imports by a wide margin, sending three times as much as Mexico and exceeding all other countries combined. During Trump’s first-term trade war, he put large tariffs on Chinese desktops, storage, and other components, only sparing laptops (until the universal tariffs last month). Yet those 1st-term tariffs were high enough to shift large subsections of the US computer supply chain—desktop imports from China peaked just as the trade war began in 2018, and overall computer imports from China peaked in 2022. It was factories in Mexico that covered those lost Chinese imports starting in 2018, it was factories in Mexico that first plugged into the resurgent US semiconductor supply chain, and it is factories in Mexico that are now supporting the US data center buildout amidst the AI boom. Last year, Mexico dethroned China as the single largest source of US computer imports even as the large east-west laptop trade continued, and computers are on the verge of dethroning cars as Mexico’s single-largest northbound export.

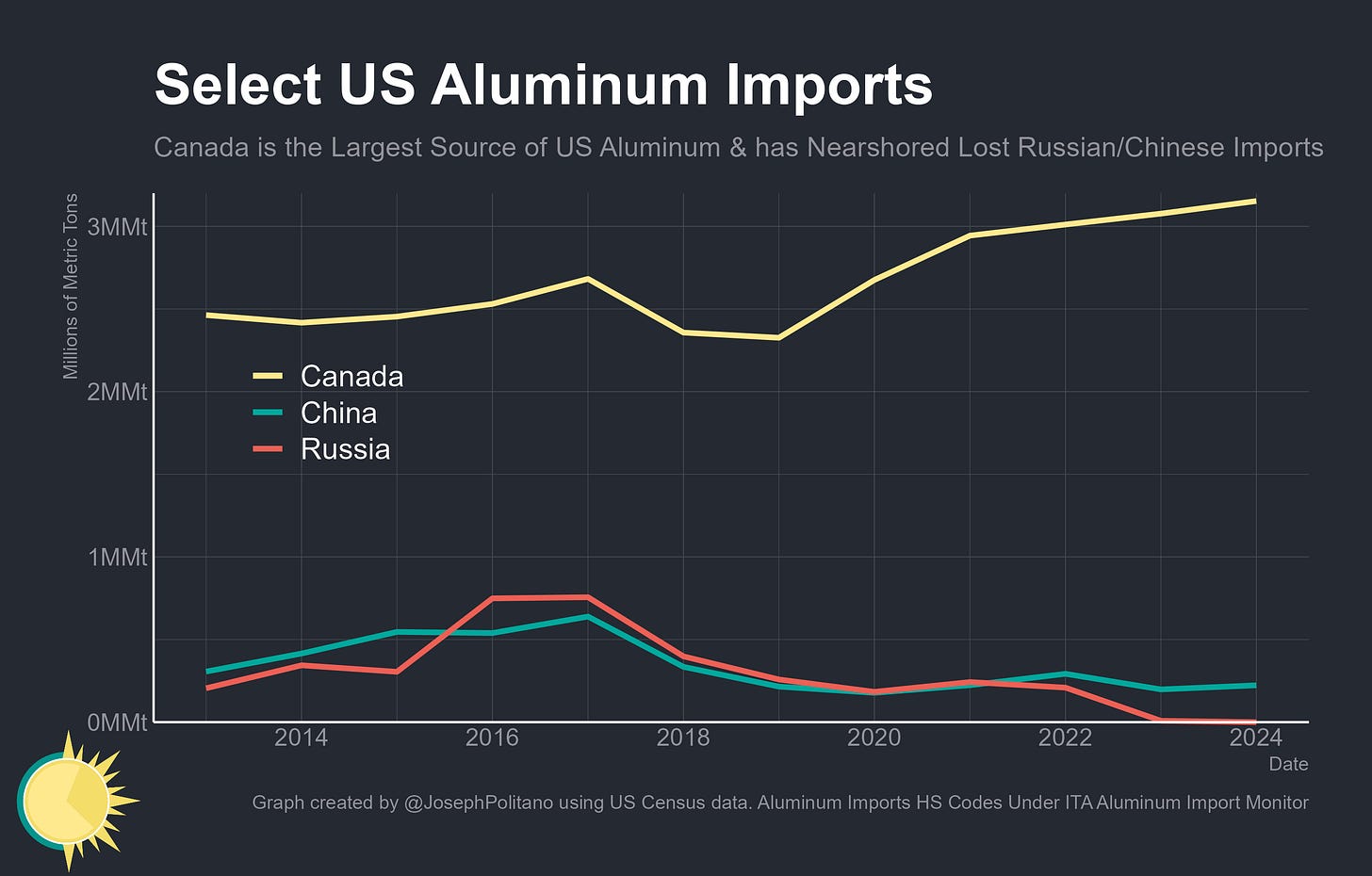

Or take Canada’s aluminum industry, which has grown to replace large chunks of what the US would once import from its geopolitical rivals. The trade war, sanctions, and the evolving aluminum tariff system from Trump’s first term all placed heavy restrictions on US imports from China and Russia, causing aluminum imports from both countries to peak in 2017. Canadian aluminum has stepped in to fill that gap, especially after Trump exempted them from the tariffs imposed during his first term. Canada has natural advantages in the sector due to its surplus of hydropower useful for the energy-intensive smelting processes, and the country’s aluminum industry has been a reliable partner for so long that it’s a key supplier for US arms manufacturers with the Department of Defense long considering it a national security asset that America could rely on even if the country was cut off from international shipping.

Both Canada and Mexico were also betting on further spillover benefits from the large industrial policy push of America’s CHIPS/IRA spending and the continuation of friend-shoring trends. Industrial fixed investment in Mexico has skyrocketed over the last four years amidst a massive government-backed infrastructure buildout and increasing private-sector industrial development. At its peak, nonresidential construction rose more than 50% above pre-COVID levels as the construction of transportation infrastructure, refineries, factories, and more grew to meet expected demand growth. Investment in the machinery and equipment needed to fill those new factories has also been continually increasing, reaching a new record high just before the end of 2024.

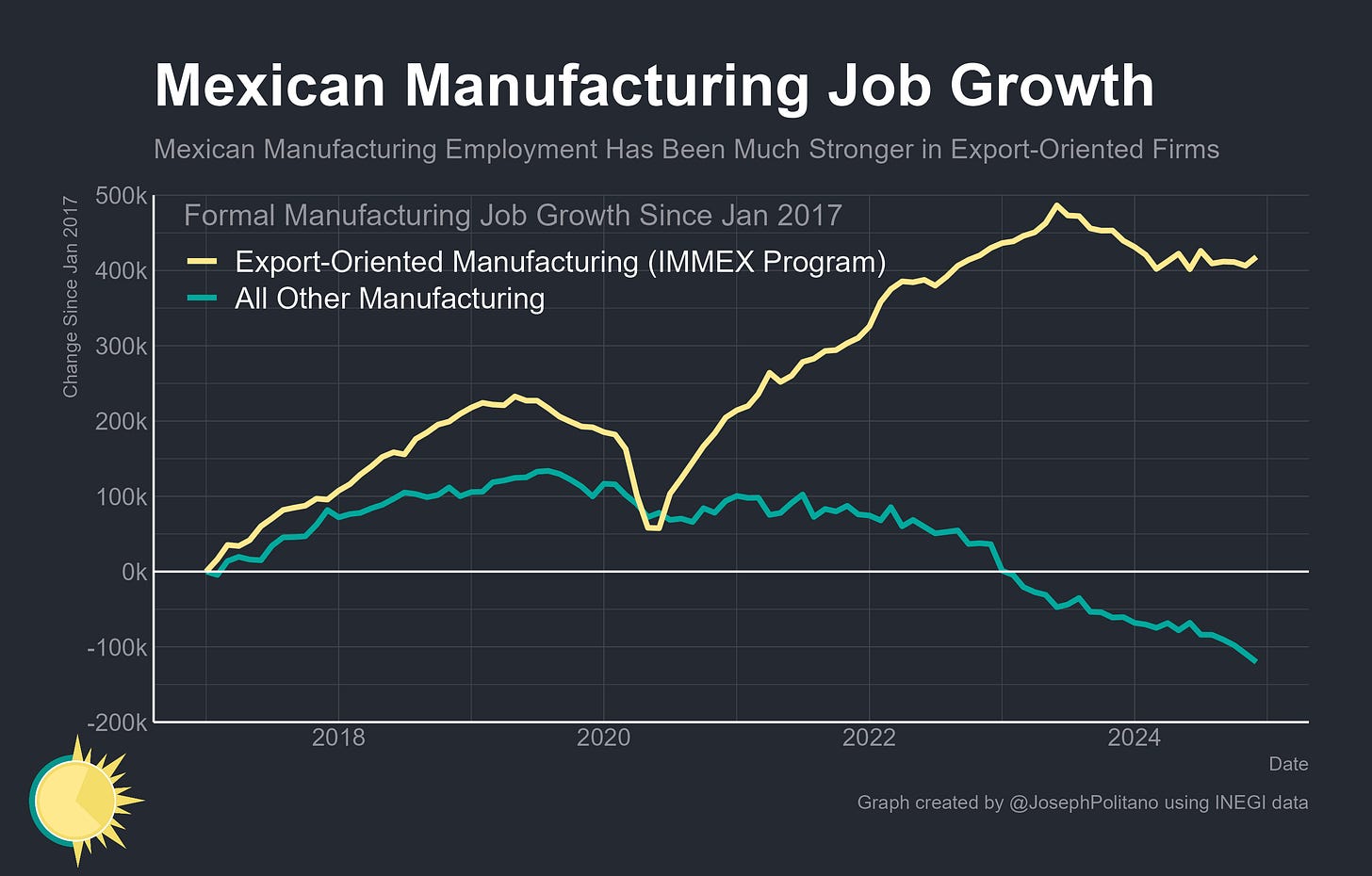

Mexico has also seen rapid employment growth within the “maquiladora” factories devoted to export industries—in fact, they’ve been the source of the entirety of Mexico’s post-pandemic formal manufacturing job gains. These near-shored jobs represent much more than simply re-packaging Chinese components—the share of Mexican value-add in its exports is currently near the highest levels on record.

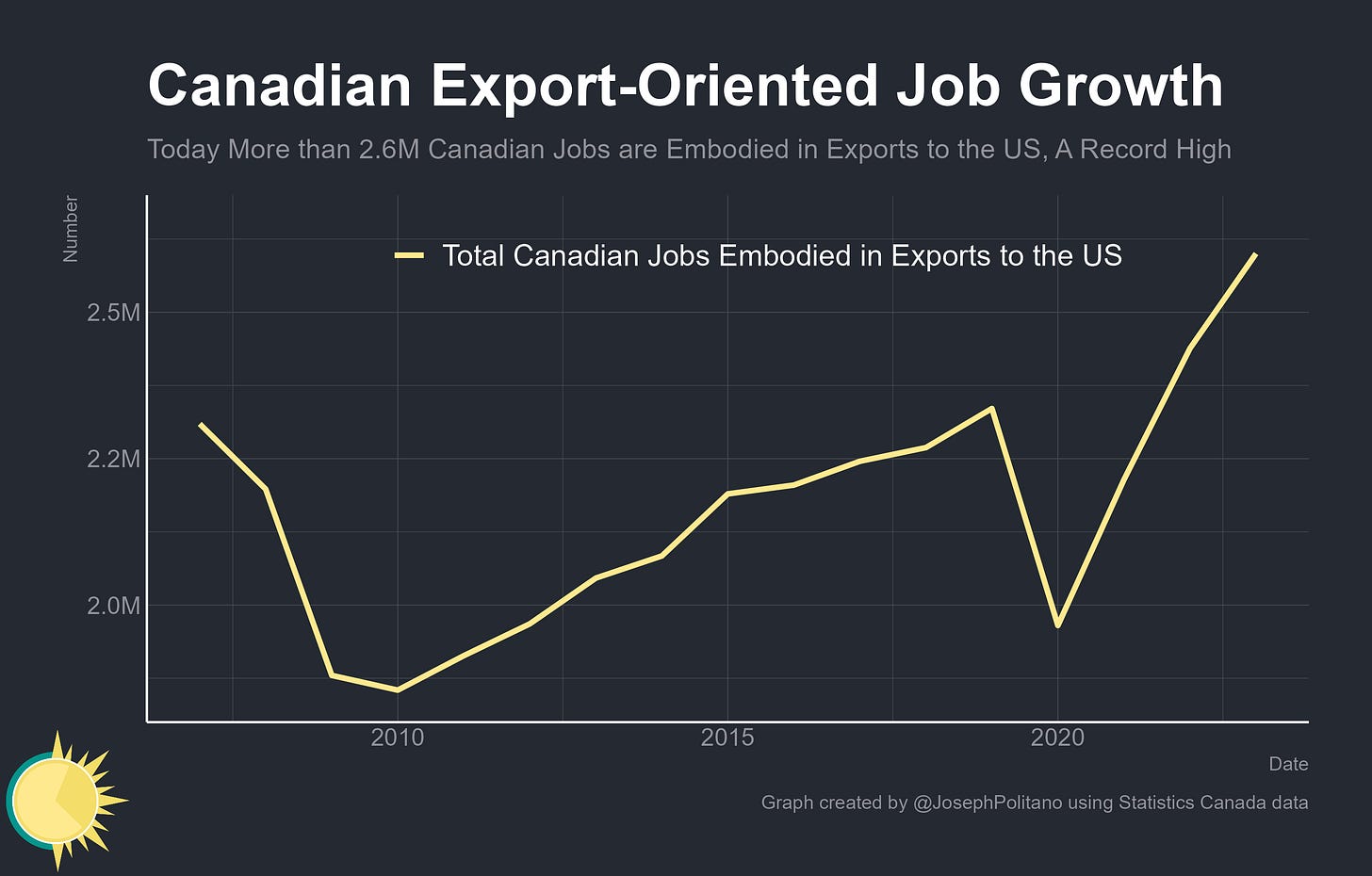

Meanwhile, more than 2.6M Canadian jobs are now embodied in exports to the US, a record high. That includes 1.2M Canadian manufacturing jobs—530k directly and 640k indirectly—numbers that have nearly entirely recovered from the impact of the Great Recession. Both countries were betting big on the continued growth of their mutually-beneficial economic partnerships with America, only for the US to try pulling the rug out from under them via massive trade wars.

Conclusions

The current US administration has wide-ranging, unclear, and shifting demands of its major trading partners—depending on the time of day, the complaint could be about immigration, economics, insufficient defense spending, drugs, or annexation. Vanishingly few of these demands are even internally consistent—basically no fentanyl comes through the northern border, Mexico is already cooperating with America’s more restrictive immigration policies, and Trump is reducing Canadians’ desire to buy US military equipment by repeatedly threatening to annex the country. Even accepting Trump’s economic arguments on the supposed destructive power of bilateral US trade deficits, tariffs on Canada don’t make sense—the country buys more manufactured goods from the US than vice-versa, with the deficit entirely explained by pipeline oil imports that Trump himself supports. The administration does not have a thought-out negotiating strategy either—“cooperation” on border and drug enforcement stalled the tariffs against Canada and Mexico for one month, but no progress satisfied Trump enough to prevent the implementation of tariffs this month, and then no subsequent concession was required for him to partially backtrack after implementation. There’s good reason why the Wall Street Journal editorial board called these tariffs “the dumbest trade war in history.”

The easy answer, then, is for the US to just stop pursuing them. Indeed, there is a decent chance Trump will once again only implement the universal tariffs on Canada and Mexico for a couple of days in April before coming up with another excuse to delay them. That would have large economic costs from chaos and uncertainty, but it would at least avoid the most catastrophic impacts of an extended trade war. Yet if he keeps his promises and implements tariffs for an extended period of time, what can Mexico and Canada do? Given its size, the gravity of the US economy is simply impossible to escape—yet there are still some options available to minimize the harm.

For one, Mexican and Canadian leaders have an extremely strong mandate from voters to stand up to US tariffs. Mexican President Sheinbaum is perhaps the most popular democratically-elected leader on the planet right now, and Canadian figures like Justin Trudeau, Mark Carney, or Doug Ford have seen their popularity jump after taking tougher stances on the trade war. Trump’s position, by contrast, is likely to cost him popularity over time—already, his approval ratings are slipping as most voters oppose his Canada/Mexico tariffs and say he’s not prioritizing addressing the high cost of living. The two countries can possibly force Trump to backtrack by outlasting him politically even if they cannot economically—and making the fight even more politically costly by targeting Trump-aligned constituencies for retaliation has already been core to their strategy.

For two, they could use the economic crisis generated by tariffs as a way to push through much-needed economic reforms. One of the best ways to stop Canadian steelworkers and lumberjacks from losing jobs would be reforms to address the country’s chronic underproduction of housing. Mexico could seize the moment to push for a stronger response to the pre-tariff economic slowdowns or make reforms to the nation’s struggling oil sector. In an extended trade war, both countries are likely to double down on more public infrastructure investment.

For three, Mexico and Canada will not be alone in their battle—universal tariffs on key goods plus Trump’s promised sector-specific tariffs are slated for April 2nd and will start trade spats with most of the world’s major economies. That move will make it more difficult for Americans to just swap Mexican-made computers for Japanese-made ones, thus increasing the share of trade war harms absorbed by the US. Conversely, it will likely make it easier for Mexico and Canada to pursue deeper overseas trade ties—something both countries are actively encouraging.

Vanishingly few details on those April 2nd tariffs have been released even as the date rapidly approaches, but they promise new trade wars on other close US allies like the European Union, Japan, South Korea, India, Australia, and more. Although none of those countries would be hit nearly as hard as Mexico or Canada, the combined effect on the US and global economy could be massive—perhaps marking the bitter end of the nearshoring policy movement once and for all.

Canadian here. We are all willing to concede that there were areas of our relationship that needed improvement, but what's upsetting us/pissing us off is the hostility and the capriciousness of it. We're trying to figure out "what do you want?" Fentanyl is obviously just a pretext for IEEPA, because we have no idea what we're supposed to do about it (sure, "fighting crime" is a good thing, but if the US can't even keep drugs out of *prisons*, 100% security of a 9000km border is impossible). There's no way they want us to be "the 51st state" because they'd never let us vote in US elections. (we'd be a very big, very blue, very ticked off state that just lost its health insurance). They can't possibly want to sell us more milk or deal with some other minor trade irritant (they are generating so much ill-will that nobody will ever want any of their products again). They claim they want "manufacturing to move back to the US", but that takes *years*... nobody is going to make investment decisions based on a tariff that could be cancelled next week.

always amusing to hear trump voters say "with trump the world will respect us again" when in reality he has turned america into a pariah state