The 2024 Economic Outlook: Growing Confidence

10 Charts on Where the US Economy is Headed in the New Year—and Why Economic Uncertainty is Falling

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 37,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

The US economy entered 2023 on the back foot, still reeling from supply shocks as inflation stayed elevated and growth remained tepid. Federal Reserve projections implied that a rapid increase in unemployment would be necessary to fully contain inflation, and consensus forecasts thought it was likely the US could soon enter a recession. Then, economic data started beating forecasts—with growth coming in hotter and price pressures coming in cooler—and then beat them again, and then again, and then again, repeatedly forcing 2023 growth projections to be revised upward until eventually many recession calls were indefinitely delayed. Policymakers became convinced a soft landing was not only possible but perhaps the most likely outcome—in defiance of prior expectations.

Beating expectations in 2023 has steadily raised expectations for 2024—growth forecasts have increased over the last several months, and the unemployment rate is projected to peak only a bit above current levels. Additionally, and perhaps most importantly, economic uncertainty is on the decline for the first time in a long time—households, businesses, policymakers, and forecasters feel more confident in their current positions and outlook than at any time since 2019, marking 2024 as an important turning point in the economic renormalization from the pandemic and ensuing inflation-fighting of the last two years.

Growing Confidence

Perhaps the most important source of growing confidence comes from within the Federal Reserve itself. At the September and December Fed meetings, Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) participants signaled that the extreme uncertainty that had characterized the totality of the last four years was beginning to end. The net share saying uncertainty about future inflation, GDP growth, and unemployment was “above-normal” fell to the lowest levels since the start of the pandemic, though it remained well above the relatively muted uncertainty of the late 2010s.

Consumers’ uncertainty about inflation has also steadily fallen over the last year and a half, though it remains relatively high. Households’ inflation expectations themselves have likewise mostly normalized—with 3-year expectations hitting pre-COVID levels and 1-year expectations remaining only slightly elevated. However, to the extent inflation expectations are relevant to the actual economic decision-making of households, uncertainty limits the beneficial effects of re-anchored expectations by reducing the confidence to act and by limiting the ability to plan. The uncertainty around forecasts of personal finances and expenses is also likely part of recent weak consumer sentiment numbers, particularly as it relates to consumer durables and other big-ticket purchases.

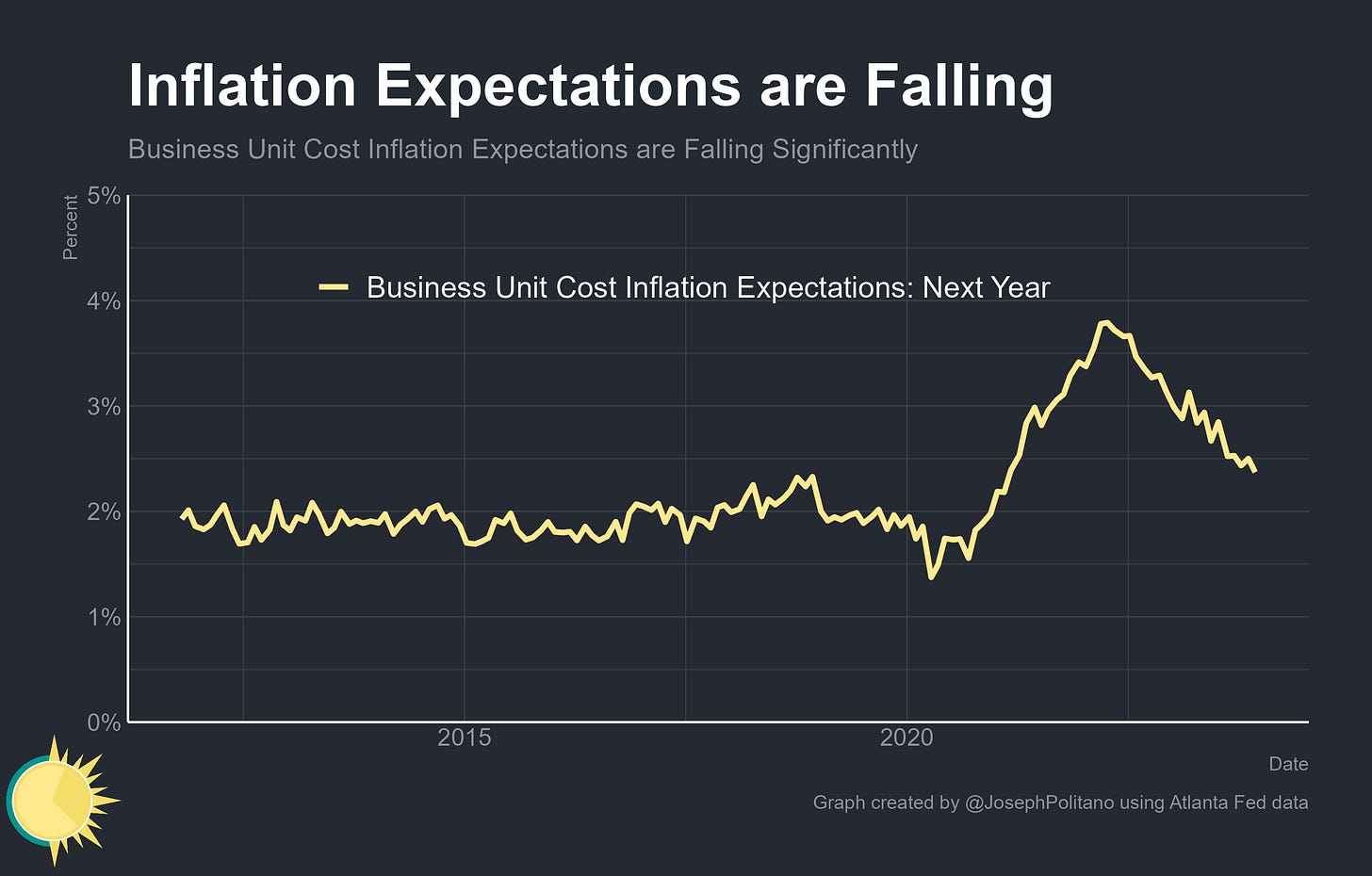

Meanwhile, more robust business unit-cost inflation expectations have continued to drop and are now at the lowest levels since the initial inflation surge of early 2021. These numbers survey those most rationally attentive to price movements, ask narrowly about firm-relevant prices in which businesses have expertise, and most importantly are tied directly to those businesses’ future pricing decisions, making them among the most well-founded measures of inflation expectations. Compared to this time last year, falling contributions from nonlabor costs, margin adjustments, and labor costs have led to decreases in unit cost inflation expectations. Not only have these inflation expectations declined, but the variance in expectations between firms has also decreased as the abatement of price pressures became a more widespread phenomenon.

More broadly, American businesses’ economic uncertainty has also dropped to the lowest levels since early 2020. Firms have more confidence in their year-ahead employment and revenue forecasts than at the start of either 2021 or 2022, and those forecasts themselves have moved closer to “normal” levels. Revenue growth expectations have steadily declined to 4%, down from the highs of nearly 7% set in mid-2022 and in line with what would be expected given a 2% inflation target. Meanwhile, employment growth expectations have rebounded to just under 1% from the lows of 0.5% set this summer.

Overall employment expectations have held up in large part because hiring plans in the service sector have remained stable despite the turbulence of the last year and a half. Both of the major service-sector surveys done by regional Federal Reserve Banks show payroll growth expectations holding at pre-pandemic levels after declining significantly in 2022.

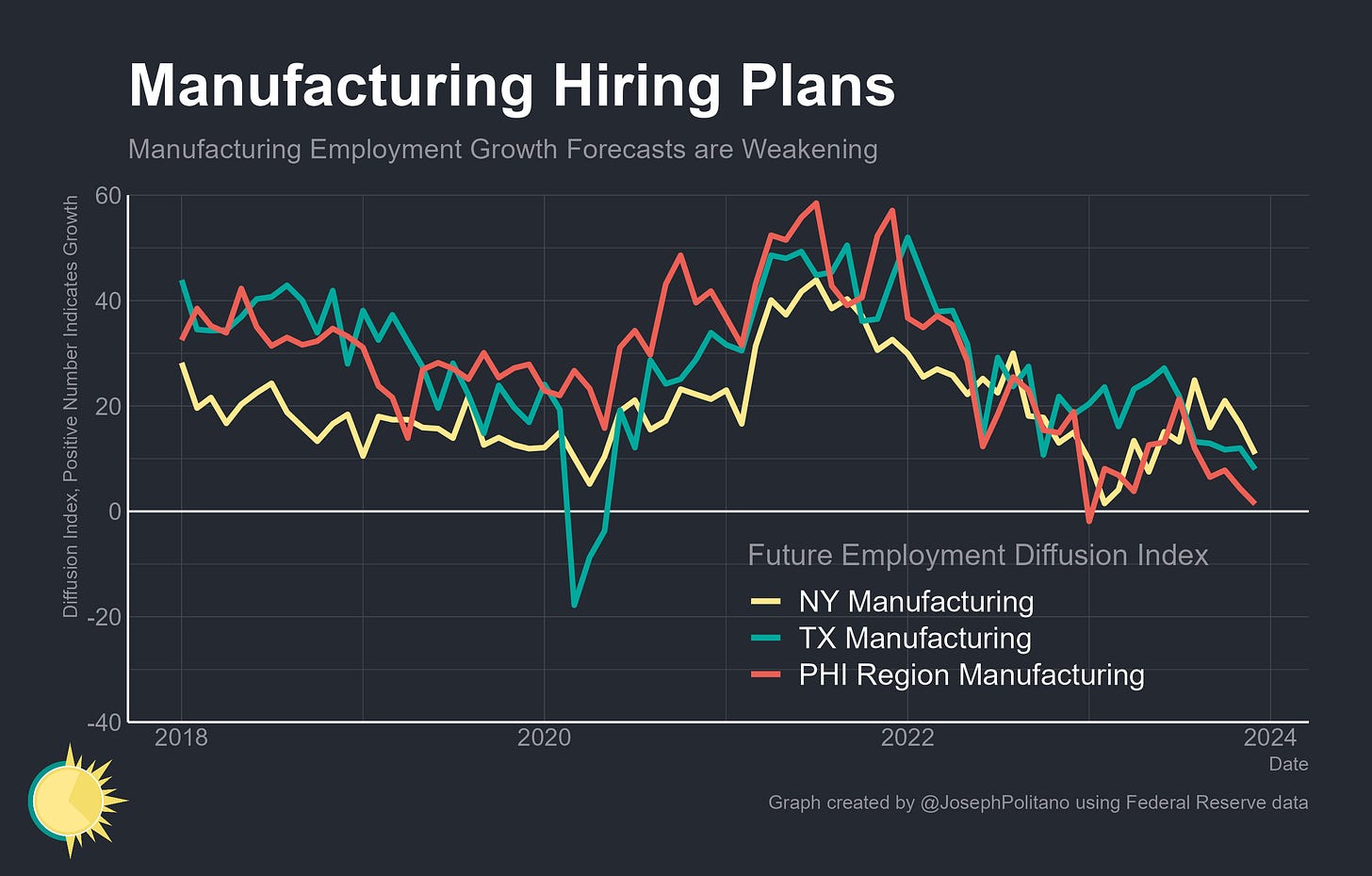

However, American manufacturers find themselves in a more precarious position. Industrial activity has been contracting throughout 2023 as the unwinding of pandemic-era bullwhips, shrinking backlog of orders, and slowing of overall goods demand weighs on business decision-making. Employment growth expectations remain weak and below pre-COVID levels, though still positive for the time being. A similar dynamic is occurring in America’s oil and gas sector, where recent price drops are causing slowdowns in growth and reevaluation of future hiring plans.

In the construction sector, confidence is picking up as mortgage rates sink significantly below the 8% peaks seen in the fall of this year and the Fed starts prepping for possible rate cuts throughout 2024. Professional forecasters see housing starts remaining at roughly their current level of just under 1.4M a year in 2024, although those projections were made before recent mortgage rate declines and are liable to be revised up. Yet in housing, too, certainty is coming back—the dispersion of year-ahead forecasts for housing starts is at the lowest level in more than 5 years.

Consumers’ uncertainty about the direction of home prices is also falling, although it remains elevated by historical standards—while home price growth expectations now precisely match pre-COVID levels, price growth uncertainty remains higher than at any point between 2014 and 2020. Sentiment about the housing market also remains near the lowest levels on record, in part thanks to this dearth of confidence that is slowly being fixed.

Conclusions

Yet shifts in certainty are not the only story of 2024—the balance of risks within the economy has also changed significantly. The FOMC’s perceived risk of rising unemployment has fallen to the lowest level since early 2022, the perceived risk of falling GDP growth has fallen to the lowest level since late 2021, and the perceived risk of rising core inflation has fallen to the lowest level since early 2021. That’s given them more space to breathe in their policy decisions and growing confidence in their ability to renormalize monetary policy—hence why 2024 looks like it may be the end of the paradigm where the fight against inflation was the be-all-end-all of Fed policy.

You really should define acronyms like FOMC that are used all over your article.

QQ: Why does the Manufacturing Hiring Plans trends down when, in your other tweet, the US Manufacturing Construction Investement has never been higher? Does it simply mean the contruction was going on outside of the three areas shown in the Hiring Plans?