The Bearish Fed

The Federal Reserve Now Believes Significant Pain—and Likely a Recession—is Needed to Stop Inflation

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 15,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

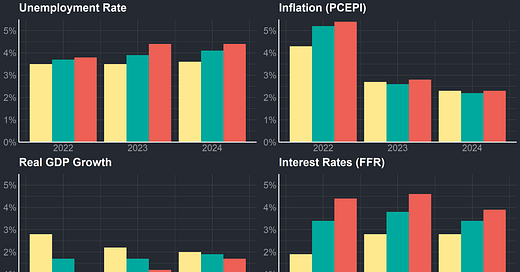

At the beginning of this year, the Federal Reserve had just started raising rates and tightening monetary policy—but remained relatively sanguine about inflation. The median Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) participant forecasted that inflation would return to target by the end of 2022 and that unemployment would remain near-historical lows of 3.5% through 2024. Even through March, Jerome Powell and ilk were still waiting for supply and unwilling to crush demand—though they were unlikely to say so explicitly.

Since then, the Federal Reserve has gotten increasingly bearish about the state of the economy and the amount of real pain necessary to stop inflation. The FOMC now expects higher interest rates, lower real GDP growth, and higher unemployment across the next two years—and for the inflationary surge to only fully subside by 2025. Critically, this increased bearishness comes even as some critical supply elements—like oil and motor vehicles—improved significantly since the Fed’s last projections in June. The projected 1% increase in the unemployment rate in 2023 would functionally signify a recession in the US.

We are taking forceful and rapid steps to moderate demand so that it comes into better alignment with supply. Our overarching focus is using our tools to bring inflation back down to our 2 percent goal and to keep longer-term inflation expectations well anchored. Reducing inflation is likely to require a sustained period of below-trend growth, and there will very likely be some softening of labor market conditions. Restoring price stability is essential to set the stage for achieving maximum employment and stable prices over the longer run. We will keep at it until we are confident the job is done.

The message from the Fed is clear: they believe demand must be contained to fight inflation, and that containing demand will require real economic pain.

Does the Fed Want a Recession?

Once per quarter, FOMC participants publish the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP), their near and long-term forecasts for a suite of economic variables under “appropriate monetary policy.” The SEP is invaluable for getting a hold of what participants themselves, not staff or models, believe will happen to the economy. But the SEP is also frustrating because the projections aren’t matched across members or across indicators—if participants have radically different ideas of what “appropriate monetary policy” entails, they will project radically different unemployment/inflation/interest rates.

Of course, these projections do not represent a Committee decision or plan, and no one knows with any certainty where the economy will be a year or more from now.

Jerome Powell, September FOMC Meeting Q&A

So the SEP isn’t strictly a Fed forecast or wishlist—but with that being said, the Fed projections from this meeting were uniformly pretty grim. All but one participant forecasted an increase in the unemployment rate in 2023, and two participants estimated unemployment would reach 5% by the end of the year. The median and most common forecast was for unemployment to reach 4.5%—basically a full 1% higher than the 2022 low of 3.5%.

An unemployment increase of that size has always coincided with a recession in the US—there is no example from American history where a recession has not entailed a 1% increase in unemployment or where a 1% increase in unemployment has not entailed a recession. Of course, a 4.5% unemployment rate would still be low by historical standards—equivalent to the level of 2006 and 2017—but that would likely leave US employment levels below pre-pandemic levels, well below historical highs, and even further below comparable high-income nations.

The projections, at this point, entail a long period of restrictive policy that boosts unemployment and hampers growth in 2023—followed by rate cuts in late 2023/early 2024 and through 2025 that get growth back on track but only manage to stem the fall in unemployment. Were these projections to occur as written, it would entail a “minor” recession—a smaller downturn than basically everything in the US historical record, but a recession nonetheless.

Higher for Longer

Restoring price stability will likely require maintaining a restrictive policy stance for some time. The historical record cautions strongly against prematurely loosening policy.

Jerome Powell, September FOMC Meeting Q&A

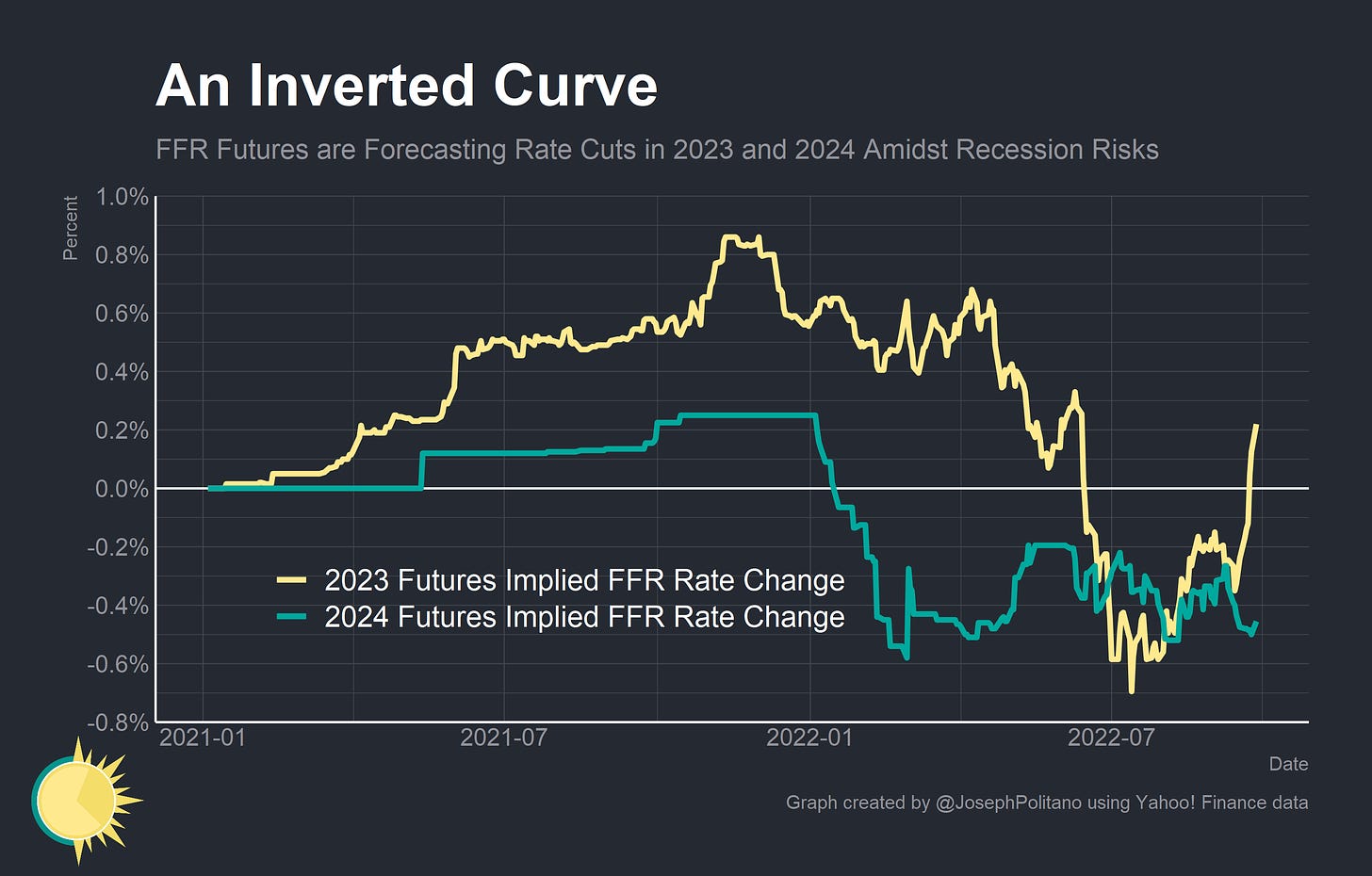

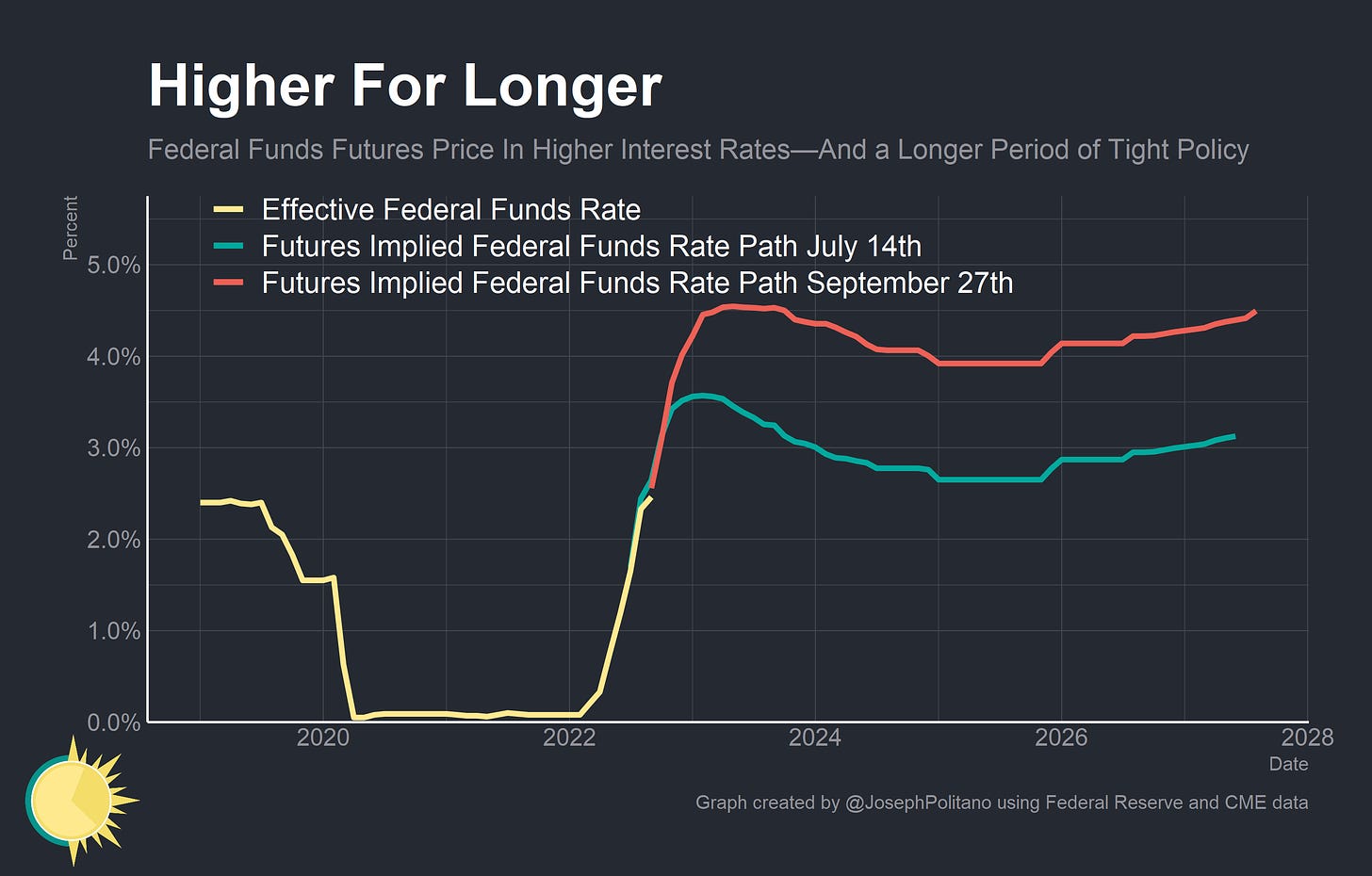

Over the last few months, the Federal Reserve has been talking up interest rates—insisting that they will remain “higher for longer”—and at this point markets have been forced to listen. Interest rate futures have stopped forecasting rate decreases in the whole of calendar-year 2023 (though some rate cuts are still forecasted for the tail end of the year), have shifted more of their expected cuts to 2024, and are pricing in higher overall long-run interest rates.

Interest rates are now expected to keep rising into early 2023 before holding at 4.5% for the bulk of the year, only declining slightly by the start of 2024. The total amount of rate cuts expected through 2023/2024 has gone down considerably—which, combined with the deterioration in projections for real economic outcomes, paints the picture of a Fed that is willing to be less responsive to economic downturns in order to ensure that inflation returns to their 2% target.

Real Pain

And if we want to set ourselves up—really light the way—to another period of a very strong labor market, we have got to get inflation behind us. I wish there were a painless way to do that, there isn't.

Jerome Powell, September FOMC Meeting Q&A

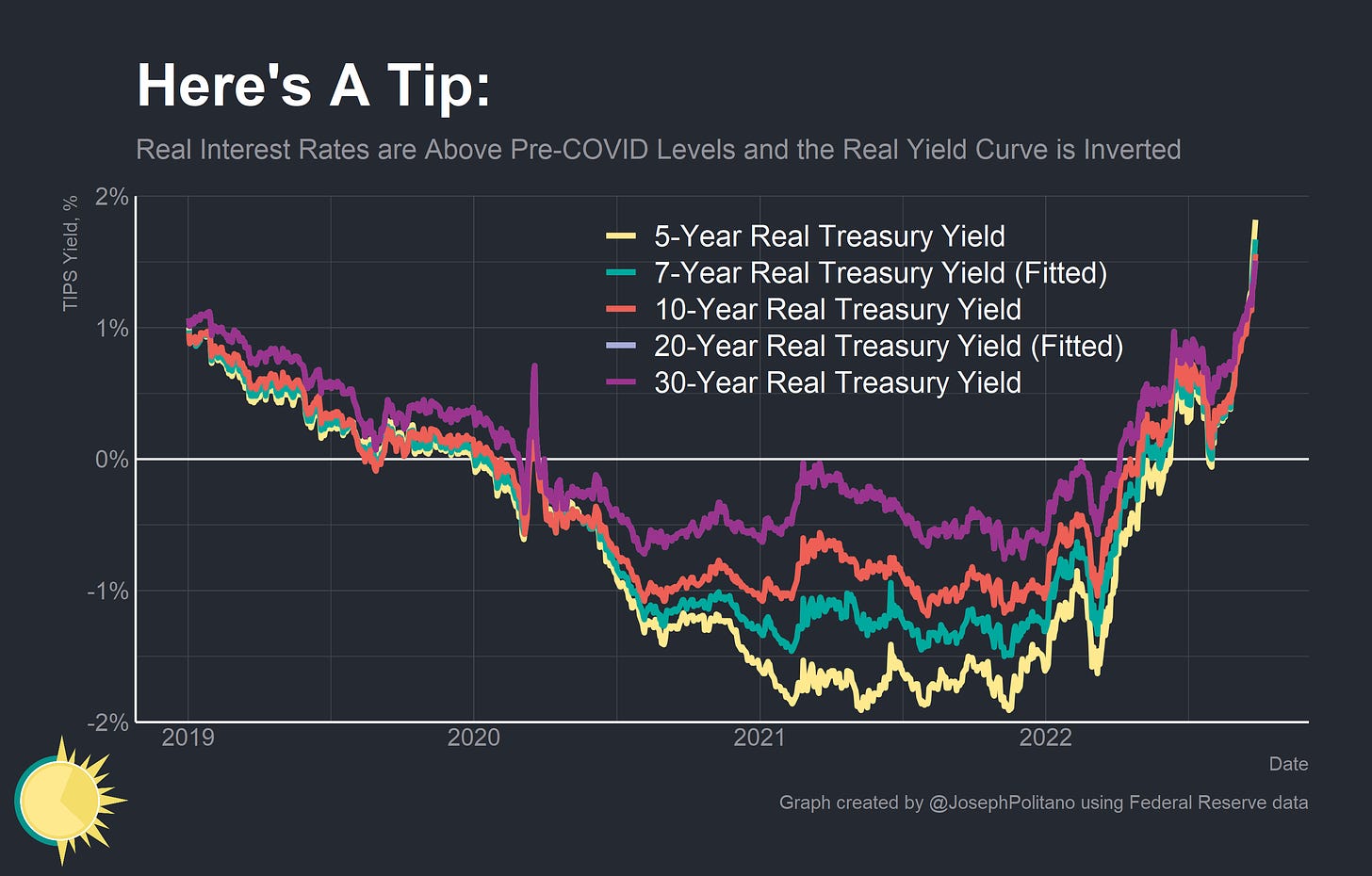

Real interest rates gave been rising dramatically since the start of this year—from significantly negative territory in January to some of the highest levels in a decade or more. 5-year real yields on US government bonds have climbed from record lows of nearly -2% last year to the highest levels since the Great Recession today. The real yield curve is also now inverted (real 5-year yields are higher than real 10-year yields, which are higher than real 30-year yields) and the size of the inversion is also unprecedented.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.