The Borrower of Last Resort

How Fiscal Policy is Taking Up Roles Usually Reserved for Monetary Policy

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

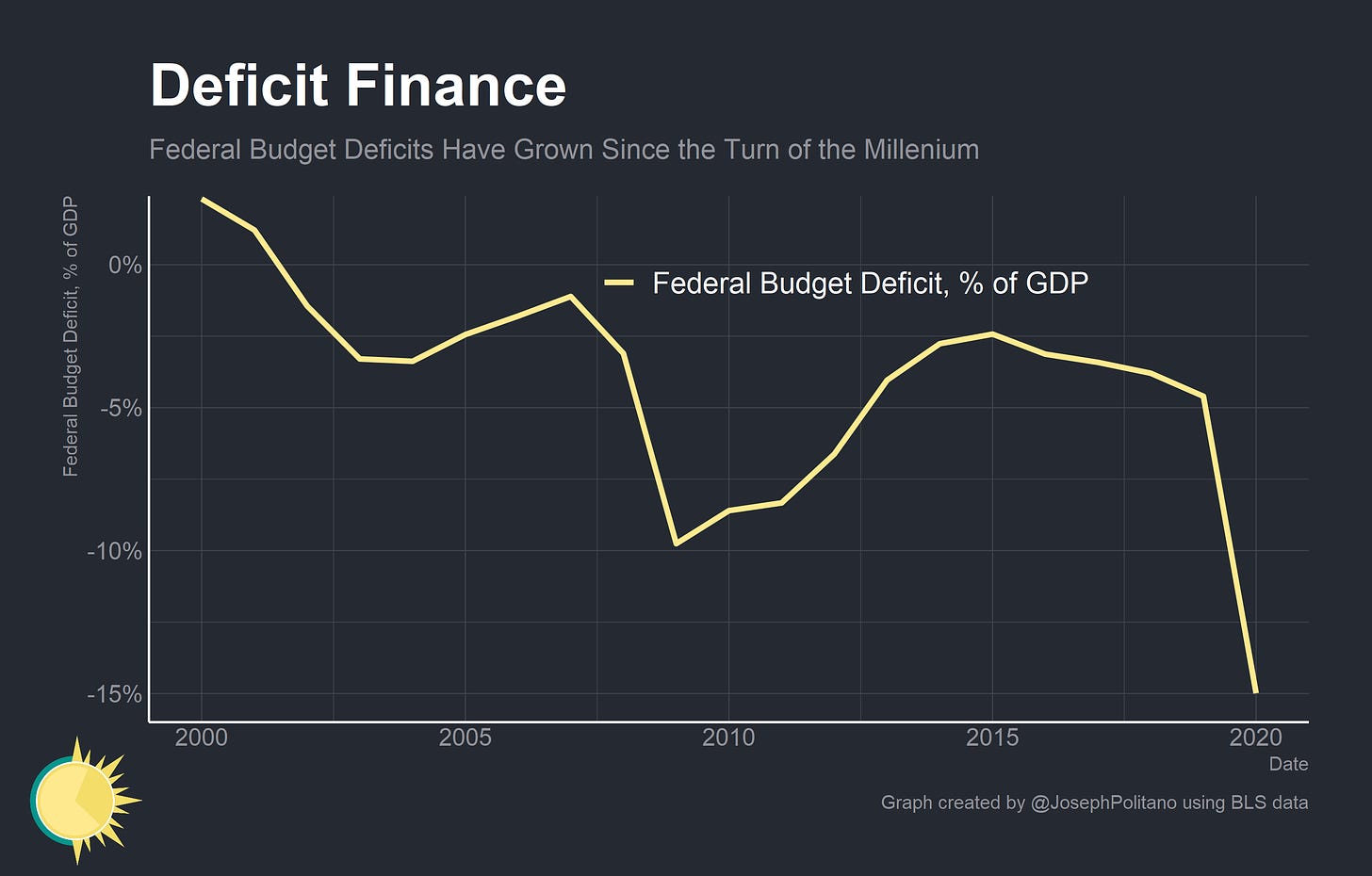

Over the last two decades, central governments in high income countries have gone on a borrowing binge. Government debt-to-GDP ratios crossed 100% in the United States, Spain, Italy, France and the UK. Japan’s headline debt crossed a staggering 200% of GDP. Yet crisis appears far from imminent—interest rates remain at record lows while government budget deficits hit their modern highs. What’s going on?

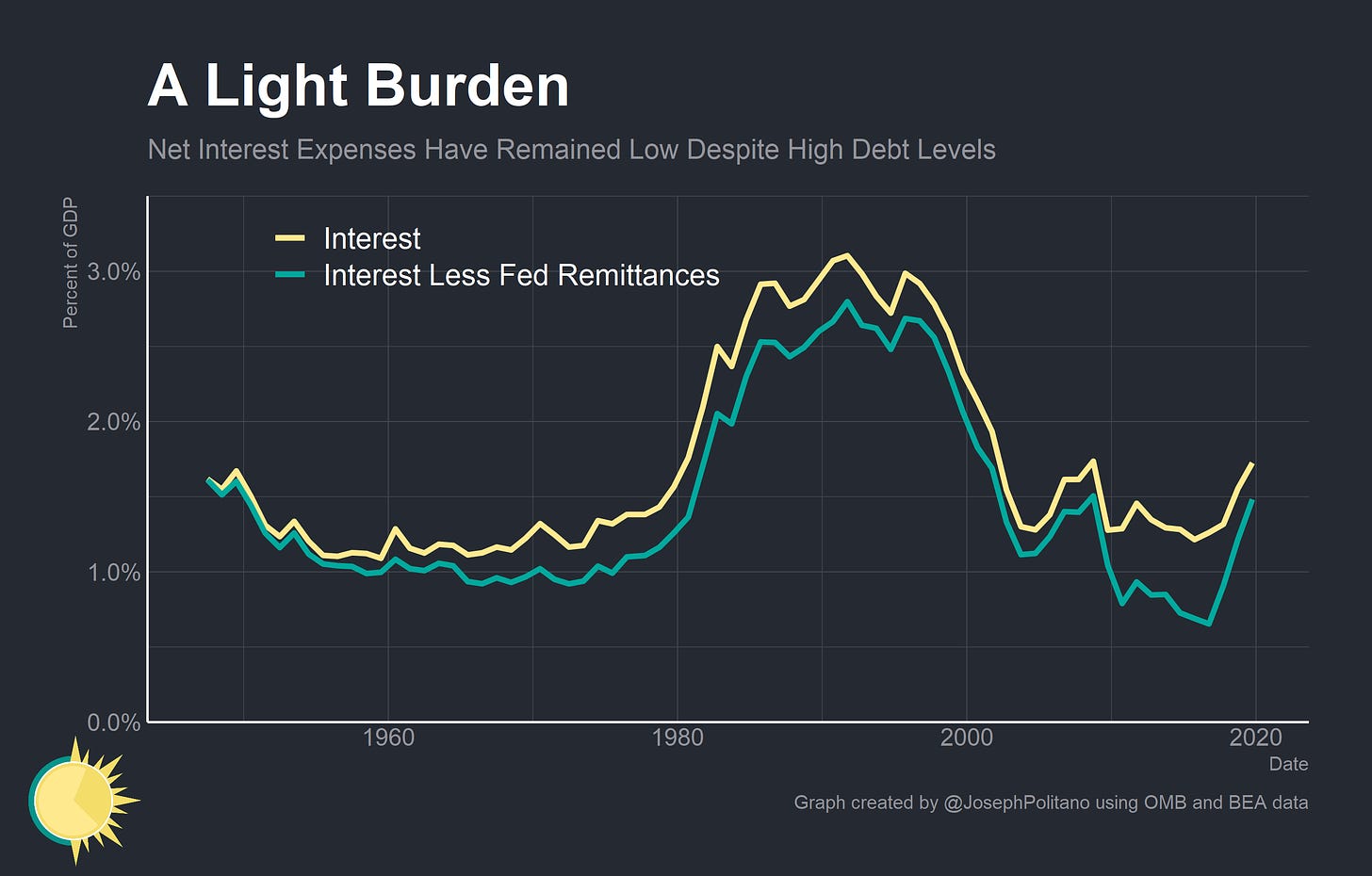

As I explained in an older post, debt-to-GDP ratios are not a good way to measure the size of government debt. Governments never have to fully repay their debt—only continually roll it over—and sovereign currency issuers can only default on obligations in their own currency by choice. Net interest costs as a percent of GDP, which effectively measure the real cost to service the debt, is instead the best measure of the size of public liabilities. Net interest costs are approaching their modern lows, and there is little sign of this trend reversing despite the large increase in government debt during the pandemic.

The combination of record-high debt and record-low net interest payments is partly a function of a sea change in macroeconomic. Shifts in economic fundamentals across high-income economies, paired with the lasting damage of the Great Recession, had forced interest rates to zero or below in many countries. With central banks unable (or more accurately, unwilling) to further stimulate nominal income growth the responsibility has instead fallen upon central governments. As the borrower of last resort, fiscal authorities are playing an increasingly important role in credit stimulation and monetary growth.

Deficits and Growth

Government fiscal debts also translate directly into private fiscal surpluses, so all else equal an increase in borrowing directly translates into an increase in private sector incomes. However, all else is not equal. In normal times, central banks essentially offset fiscal expansion in order to maintain stable inflation levels. This is why increased government debt (usually) increases interest rates—the additional stimulus is counteracted by central bank rate hikes.

However, the Effective Lower Bound (ELB, sometimes Zero Lower Bound) significantly complicates matters. In general, central banks cannot lower nominal interest rates below approximately -1% without causing unwanted complications in the financial system. Some central banks, including the Federal Reserve, refuse to go below 0%. If inflation and aggregate income growth remain low despite interest rates hitting the ELB, central banks functionally become stuck. They can communicate that future nominal interest rates will be lower (through Quantitative Easing or Yield Curve Control), but they can lower current interest rates no further.

Now, it is worth acknowledging that there are ways for independent central banks to exit the ELB. Paul Krugman advocated for a policy where central banks “credibly promise to be irresponsible”, essentially committing to keeping interest rates as low as possible for as long as needed in order to escape the ELB. Lars Svensson believed that central banks could easily escape the ELB by choosing a foreign exchange rate target that would restore inflation and nominal income growth. However, both of these options have proven politically unworkable. Central banks in many high-income nations are institutions specifically designed to be effective fighters of inflation, so it is hard for them to credibly commit to higher inflation rates. Meanwhile, exchange rate targets remain unpalatable for elected political leaders and outside the current mandates of many central banks.

So for the first time in history the majority of high-income nations are stuck at or near the ELB. This means that nominal and real output remain below the central bank’s target and therefore the central bank will not offset expansionary fiscal policy. Indeed, fiscal stimulus becomes necessary in order to restore nominal incomes and inflation to target levels and allow the central bank to eventually escape the ELB. That’s part of the reason why we have seen extremely high federal budget deficits over the last decade—fiscal expansion became necessary to boost aggregate incomes in the wake of the 2008 crisis.

Importantly, this fiscal expansion is not straining government balance sheets. Net interest expenses (which excludes the money that the Federal Reserve remits to the Treasury) as a percent of GDP hit record lows in 2017 and have remained on the low end of normal historical levels since the turn of the millennium. The low interest rates are more than compensating for the rise in federal debt levels.

Indeed, the story of the last 30 years has been a generalized decline in the servicing costs for government debt across high-income economies. The damage wrought by the 2008 Recession and the Euro crisis put particular downward pressure on interest rates across the board, more than offsetting the rise in debt levels. Interest rates on 30 year German Bonds remain are actually negative, and have been hovering around 0 since 2019. Even Japan, which has a government debt burden that totals 200% of GDP, has seen a massive decrease in debt servicing costs. Stuck near the ELB for decades, the country has relied on fiscal stimulus to support aggregate income growth. In this way massive fiscal borrowing is not enabled by extremely low interest rates—it is demanded by them.

But if the global drop in interest rates is driving the increase in fiscal stimulus, what is causing interest rates to stay so low across the board?

Interest and Growth

There are plenty of explanations, and it is a coincidence of several factors that are driving interest rates lower across high-income economies. First off, the drop in real output caused by the global financial crisis and Euro crisis left countries’ economies permanently scarred. With employment, productivity growth, investment, and dynamism down credit demand faltered and central banks were forced to lower interest rates in order to compensate. In that way, current low interest rates were caused by the previous period of too-tight policy. This also contributed to a safe asset shortage where the increased economic risk and lack of suitable alternative investments raised demand for safe assets like government bonds.

Secondly, an ageing population is pushing interest rates down across the board. People (especially in high income nations) are living longer and having fewer children, and immigration levels remain too low in most countries to make up the difference. The result is that working age populations are projected to shrink by 2060: by 40% in South Korea, 30% in Japan, China, Italy, and Spain, 20% in Germany, and 10% in the OECD overall. Anglophone countries—the US, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand—are expected to be spared this fate thanks to relatively higher immigration levels, but they will still see an aging demographic profile as people live longer. The drop in population growth reduces the demand for capacity investment while an ageing workforce represents a drag on productivity growth, pulling interest rates downward. This trend stands little chance of reversing in the long run—populations are already shrinking throughout Europe, Japan, and China and the UN expects global populations to peak in 2100 when the same trend hits South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Finally, rising income inequality is also dragging down interest rates. High-income individuals tend to consume a smaller share of their incomes and invest a much larger share of their incomes, so an increase in income inequality can be expected to drive investment demand up and consumption demand down. The result is lower interest rates. Wealth inequality has increased across many high income nations over the last several decades as the gap between college-educated workers and non-college educated workers widened alongside a drop in labor’s share of total income. Thankfully, this trend has the highest chance of ameliorating—we are already seeing wage growth among low-income Americans outpace wage growth of high-income Americans thanks to the strength of the current labor market.

Markets, though, are not optimistic that real interest rates will rise anytime soon. Real interest rates in the United States (derived from inflation-protected Treasury bonds) have been sliding since the onset of COVID and are at their lowest point in history. Part of this is actually good news—fiscal stimulus has raised market-based 30 year inflation expectations from less than 1.3% to 2.4% (which is in line with the Federal Reserve’s 2% target when you account for risk premiums and different inflation measurements). This in turn has lowered real interest rates as market participants expect the ELB to be marginally less binding than they did at the onset of COVID.

Still, nominal interest rates remain extremely low (the 30 year bond yield is only half a percent off all-time lows) despite high expected government borrowing over the next few decades. In other words, Congress will have to continue to act as the borrower of last resort in order to maintain US economic growth.

Conclusions

For decades, people have warned of fiscal dominance—a situation where extremely high government debt levels force the Federal Reserve into maintaining low interest rates in order to prevent a government default. Fiscal policymakers would essentially be holding the central bank hostage—and the result would be higher inflation. But today’s high debt levels are the result of the inverse of fiscal dominance. Central bankers are not keeping interest rates low in order to support fiscal spending, it is the fiscal spending that is compensating for too-high interest rates.

This is also why arbitrary fiscal restraints, particularly in the EU, have been so damaging to long run economic growth. The US has run large deficits over the last decade while Germany has run budget surpluses since 2014, and the result has been worse economic outcomes throughout the Eurozone. Germany’s debt is limited by constitutional restrictions on deficit spending, and most Eurozone countries’ deficits are restricted by the Maastricht treaty. These restrictions are increasingly preventing European governments from acting as the borrower of last resort, a situation that is not helped by the European Central Bank (ECB) refusing to fully guarantee all Eurozone member countries’ sovereign debt.

If central governments are going to have to act as the borrower of last resort, it is also critical that they do so in the most best way possible. Direct checks would be most efficient, especially if that spending was concentrated among low-income people and in support of families with children. The COVID stimulus checks and the expanded child tax credit represent important models for future policy to build on. More than that, though, good macroeconomic policy may increasingly require building political coalitions around increased federal spending and deficits.

great stuff, as always ... question: why does the US government have to roll over its debt? Could it not just print money to pay it off? (inflation risk aside)