The British Inflation Crisis

The UK's Economy Has Been Suffering From Weak Growth and Generationally-High Inflation—But The Worst Could Be Yet to Come

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 20,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

The UK is undergoing a generation-defining economic crisis as inflation surges above 10% and growth flatlines amidst the ongoing energy shortage. The UK was in a uniquely bad position even before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, with the country having one of the weakest post-pandemic economic recoveries of any major high-income country, still dealing with the aftershocks of Brexit, and coming off a long period of extremely lackluster growth in the 2010s—but the situation could get much worse before it gets better. The Bank of England currently forecasts that a massive, years-long recession with rapid increases in unemployment and zero economic growth through at least 2025 is necessary to bring inflation back down to 2%.

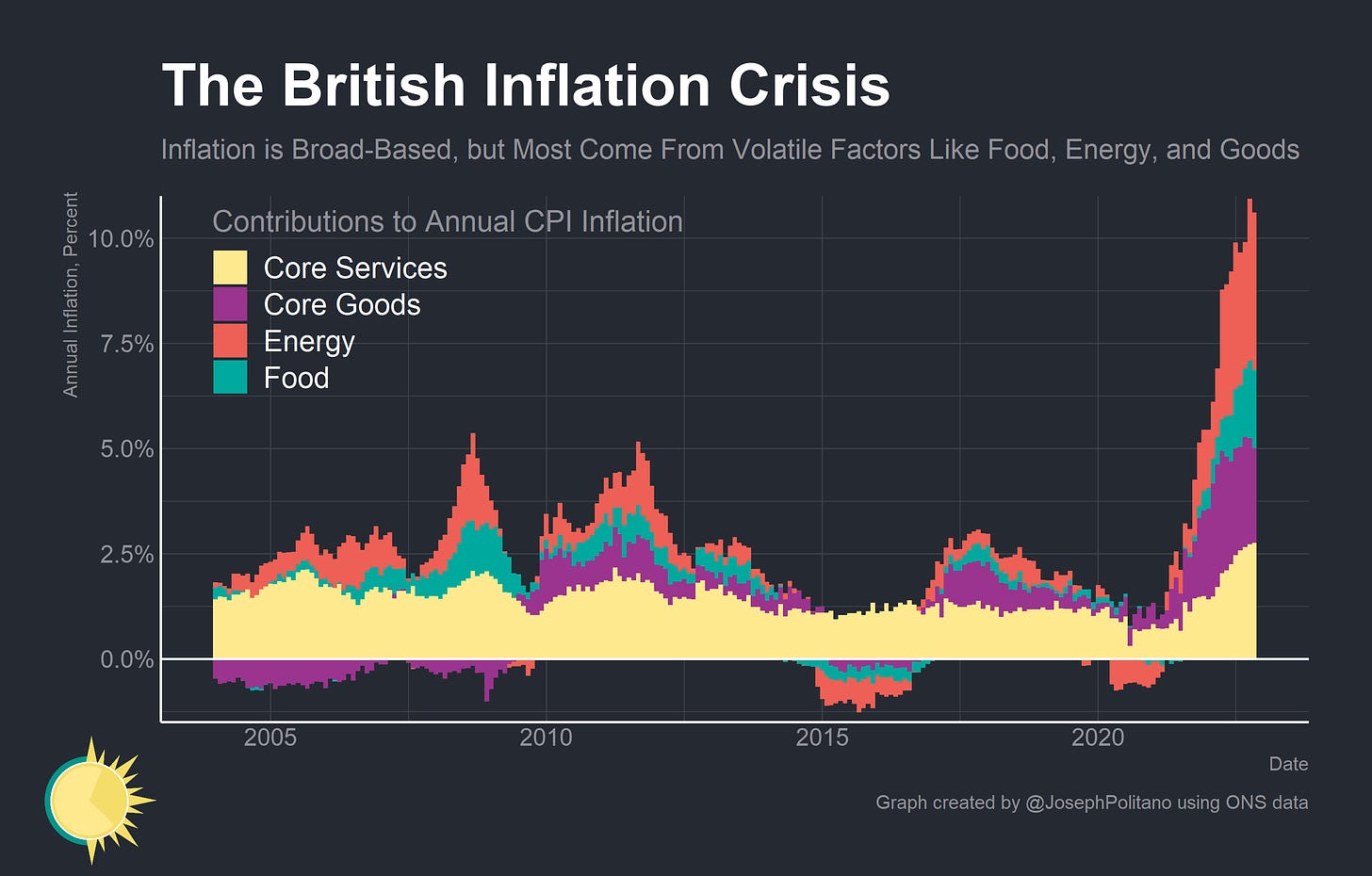

The core problem for the Bank of England is that most of the UK’s current inflation comes from volatile food, energy, and goods prices that are largely outside the normal control of monetary policy—they are tightening monetary policy into an extremely harsh energy supply shock since something must be done about inflation, and tightening is all they can do. “The [Monetary Policy Committee, MPC]’s latest projections describe a very challenging outlook for the UK economy,” reads their November Monetary Policy Report “It is expected to be in recession for a prolonged period and CPI inflation remains elevated at over 10% in the near term.” By the end of 2025, the MPC expects more than one out of every 16 Britons in the labor force to be out of a job.

Right now, there’s significant justification for the Bank of England to take a more dovish approach, with measures of British real growth, spending, and employment already showing signs of weakness and British aggregate nominal spending still below the pre-pandemic trend. Two members of the MPC voted not to hike rates at the December meeting—but given the overwhelming intensity of inflation, dovish sentiments are unlikely to completely win out. The Bank of England doesn’t see government efforts aimed at capping energy prices, adapting to the energy shortage, protecting vulnerable households, and supporting at-risk businesses as yet putting enough of a dent in the cost-of-living crisis to give them time to wait and be flexible. As the UK heads into a critical turning point, the economic outlook remains bleak.

The Cost of Living Crisis

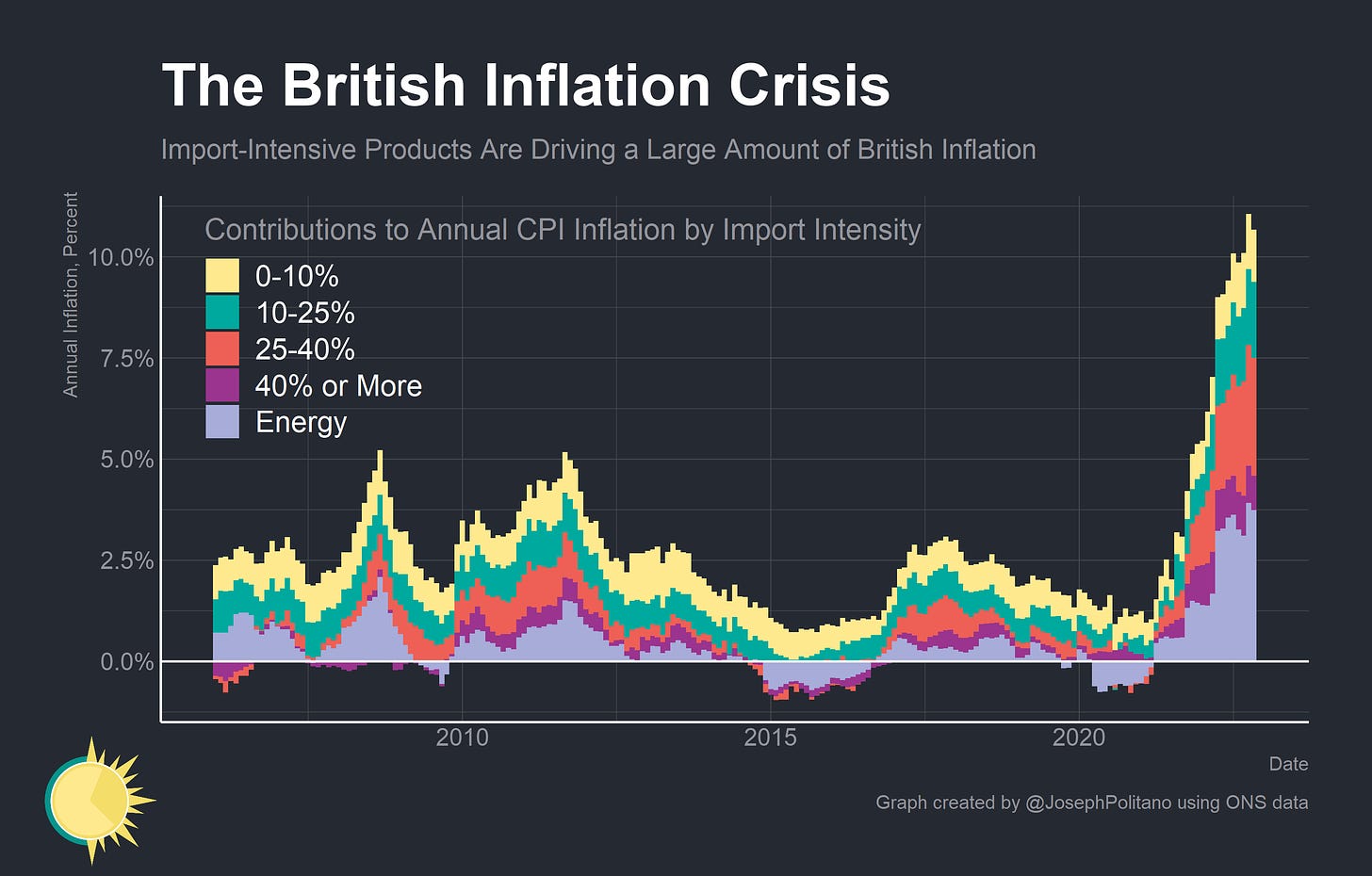

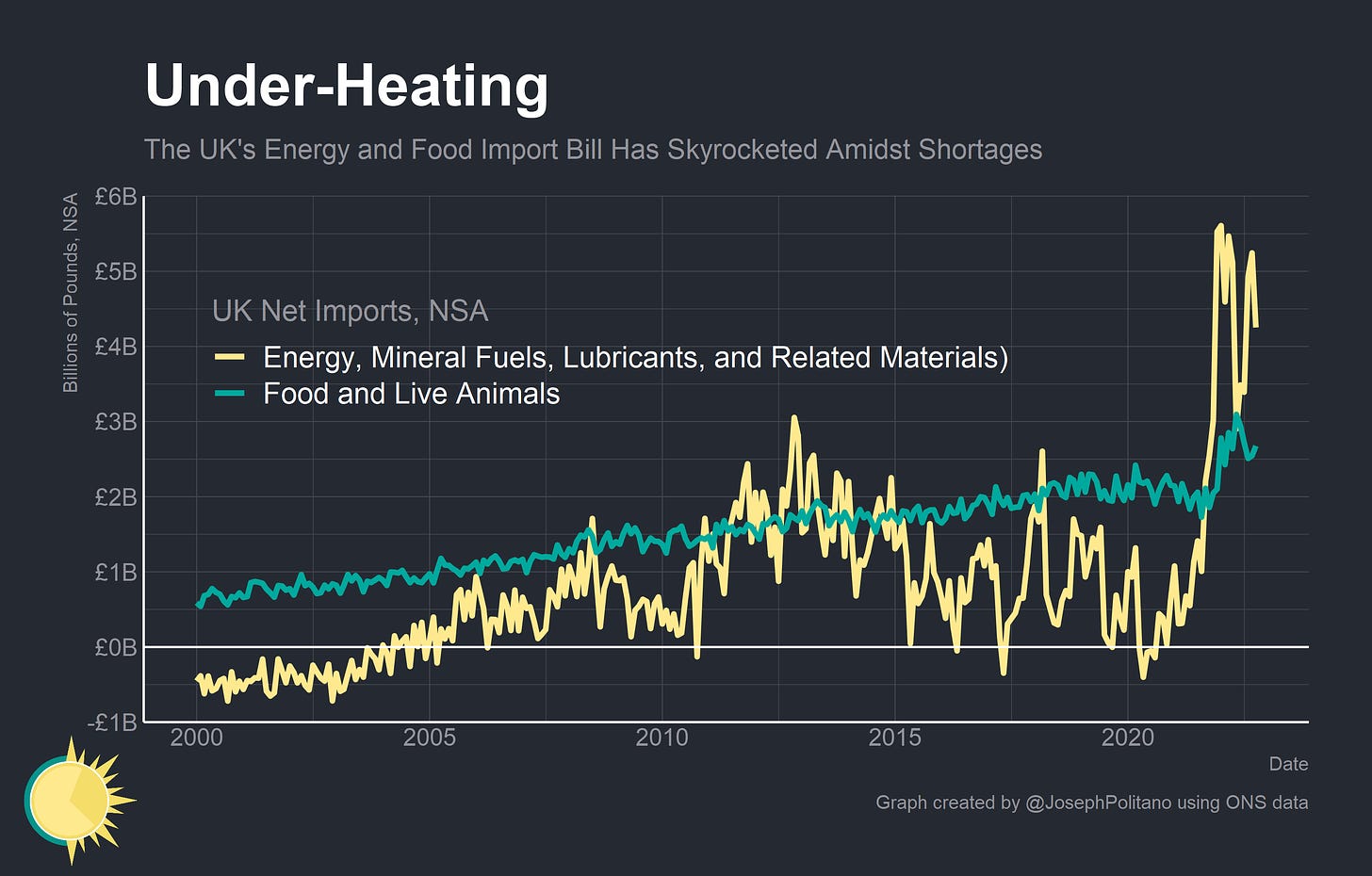

The ongoing European energy crisis has been a large reason for the British cost of living crisis—the UK imports about 50% of its total natural gas consumption, most of which historically comes from Norway. Now they are fiercely competing with continental buyers for the limited supply of piped gas and have been forced to further compete in the even-tighter international Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) markets. Energy, therefore, represents far and away the largest contributor to British inflation, practically doubling the Bank of England’s 2% target on its own despite price regulations reducing the net effect of the shortage on headline CPI. But other import categories represent a large chunk of inflation too—indeed, the post-pandemic economy has seen the contribution of items with an import intensity of 25% or higher surge to about 3.75% amidst ongoing weakness in the British Pound and rapid price hikes in imported food.

Indeed, rising food and energy prices are part of the reason for the weakened Pound in the first place—British net food and energy imports have surged to multi-decade highs in recent months, with energy imports in particular briefly exceeding £5.5 Billion per month. The UK’s exit from the European common market and the ensuing trade restrictions placed on imports and exports to the EU, though likely not responsible for a significant chunk of today’s inflation, has certainly exacerbated import price pressures and contributed to the country’s weak recovery.

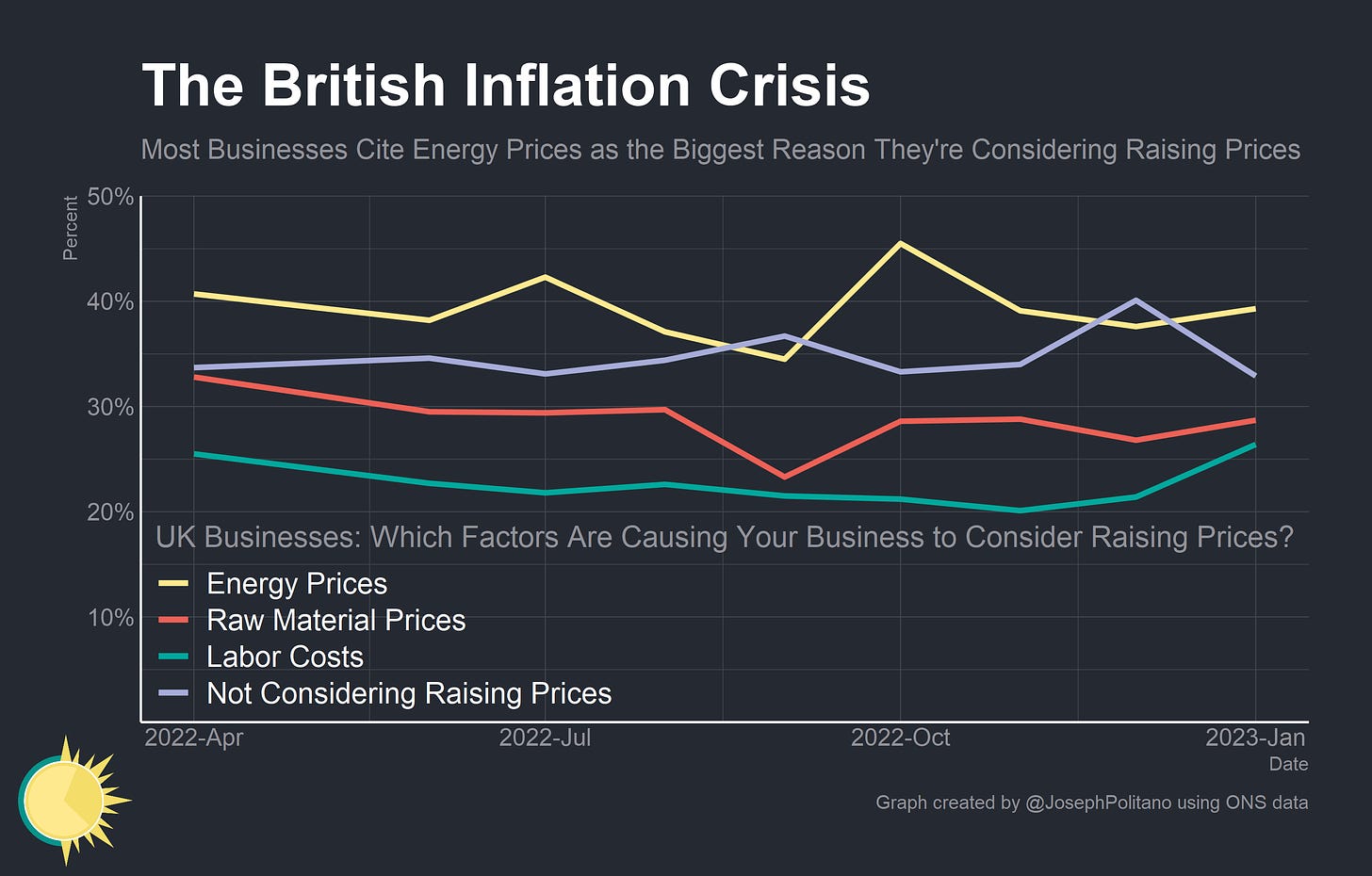

Keep in mind, also, that energy and import price pressures do not show up in the CPI only through direct influence but pass through to other sectors of the economy. Overall, nearly 40% of British businesses reported considering raising prices in the near future due to energy costs—including a staggering 80% of businesses in accommodations and food services. Materials shortages weighed next heaviest on firms’ minds, with about half of manufacturing and construction firms citing it as a reason they’re considering price hikes. Labor costs, the main listed category that central banks can lower, ranked third—though with a notable increase in recent months. The core of the dovish argument is simply that British firms see energy and supply shortages as a much bigger cause of price hikes than the factors usually influenced by monetary policy.

Another reason the Bank of England could be more sanguine is that they have largely contained the aggregate spending that is driving so much of inflation in countries like the US—British nominal gross domestic product (NGDP) has remained well under the pre-pandemic trend and aggregate nominal growth has slowed down significantly in recent quarters. These aggregate nominal metrics are what monetary policy has the most direct control over and should generally target, so the fact that inflation has returned to such a vicious degree without excess nominal growth suggests that British inflation isn’t so much a case of too much money chasing too few goods—it’s a case of persistent supply shocks inflicting massive damage on real economic capacity.

To caveat this, British NGDP growth rates remain significantly elevated—nearly 8.5% year-on-year in Q3, compared to a normal level of about 4%—as a reflection of nominal output catching up with the pre-COVID trend. That pace of growth will certainly drive up annual inflation, but only by counteracting the drop in prices caused by declining nominal growth in the early pandemic. Still, US nominal growth was below trend until late 2021, which in retrospect was not a correct justification for keeping American monetary policy so dovish for so long—but that misses further distinctions between the UK’s situation now and America’s situation then.

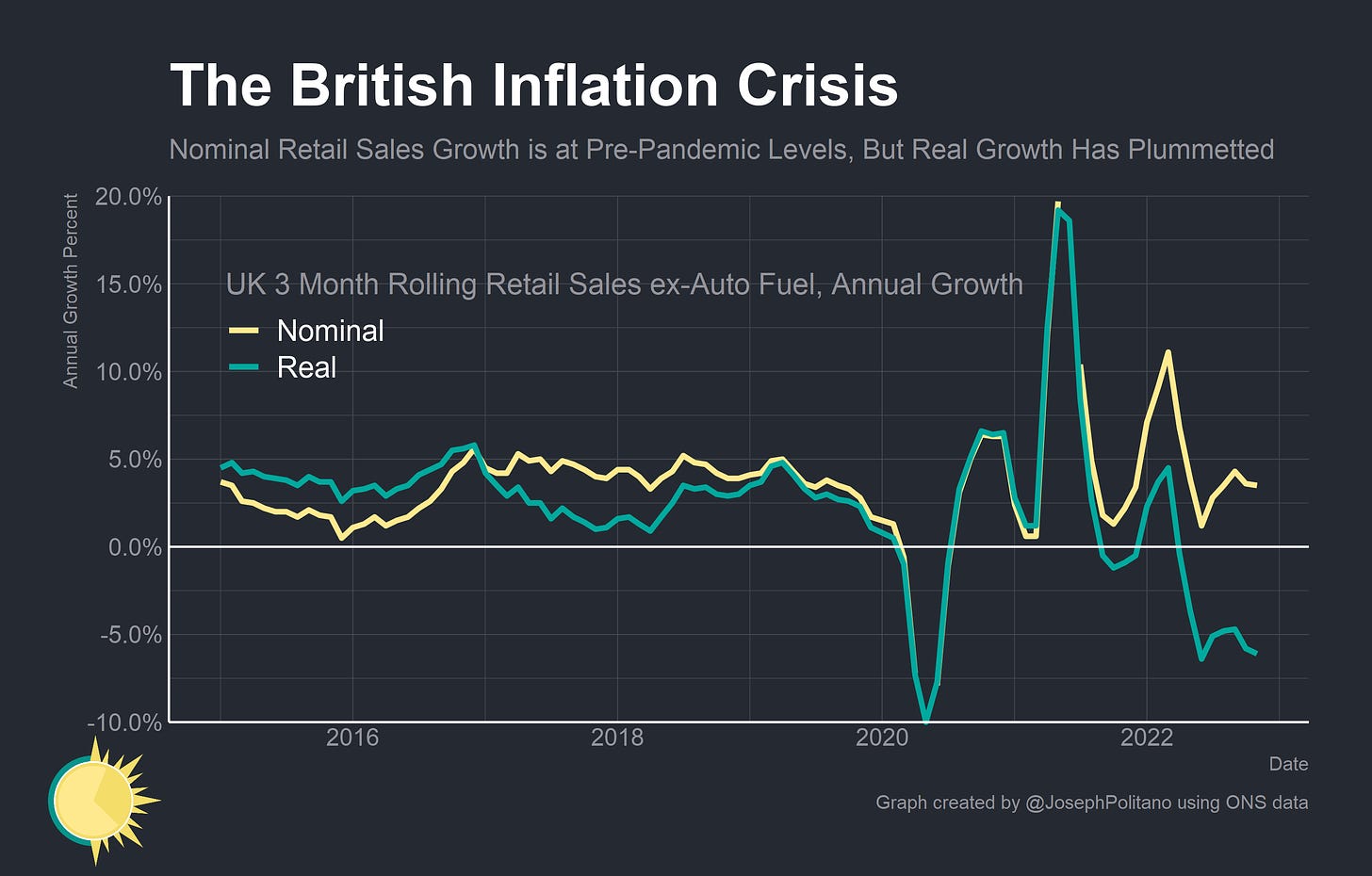

The Bank of England—and other major central banks, led by the Federal Reserve, have been tightening monetary policy for nearly a year now. Nominal GDP growth in the UK has already slowed down considerably and nominal retail sales growth has returned to a normal level—something that has not yet occurred to the same degree in the US. Some monetary tightening is necessary to keep aggregate demand in check, but the extent of the tightening currently projected by the Bank of England entails even more real economic pain than American monetary policymakers expect—meaning that British officials have essentially resigned themselves to intentionally overtightening into supply-shocks in order to explicitly induce a recession to keep inflation in check. Plus, the UK economy is already on weaker footing than its peers across the pond—with real employment, investment, and output all taking significant hits this year.

In Real Terms, the UK Lags Behind

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.