The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Like it or not, cars are a central facet of American life. 90% of Americans live in a household with a car and 3/4 of people drive alone to work (a further 1/10 carpool). 17 million new cars are sold in America each year and almost 40 million used cars change hands. The price of gasoline is arguably the single biggest factor in consumer’s outlook on the economy and their opinion of elected officials.

So it is of significant macroeconomic importance when a dire shortage of vehicles emerges. COVID-wary Americans have become more dependent on their cars than ever, driving up demand for vehicles of all stripes. A supply chain crisis mixed with planning mistakes from manufacturers, dealerships, and companies in the transportation industry has caused a drop in total vehicle output. In short, American demand for automobiles has spiked while most manufacturers struggle to maintain pre-pandemic levels of production, driving up short term aggregate inflation and dampening economic growth.

Fixing the car crisis will require time, but is a necessary part of cleaning up the damage COVID-19 has wrought on the economy. A global shortage of semiconductors will need to be solved for automobile manufacturing to return to pre-pandemic levels. School bus service and other public transportation networks will need to be restored for transportation capacity to renormalize. Dealerships will need to restore inventories for prices to decline again.

Here’s how we got into this mess, and how we get out.

Breaking and Accelerating

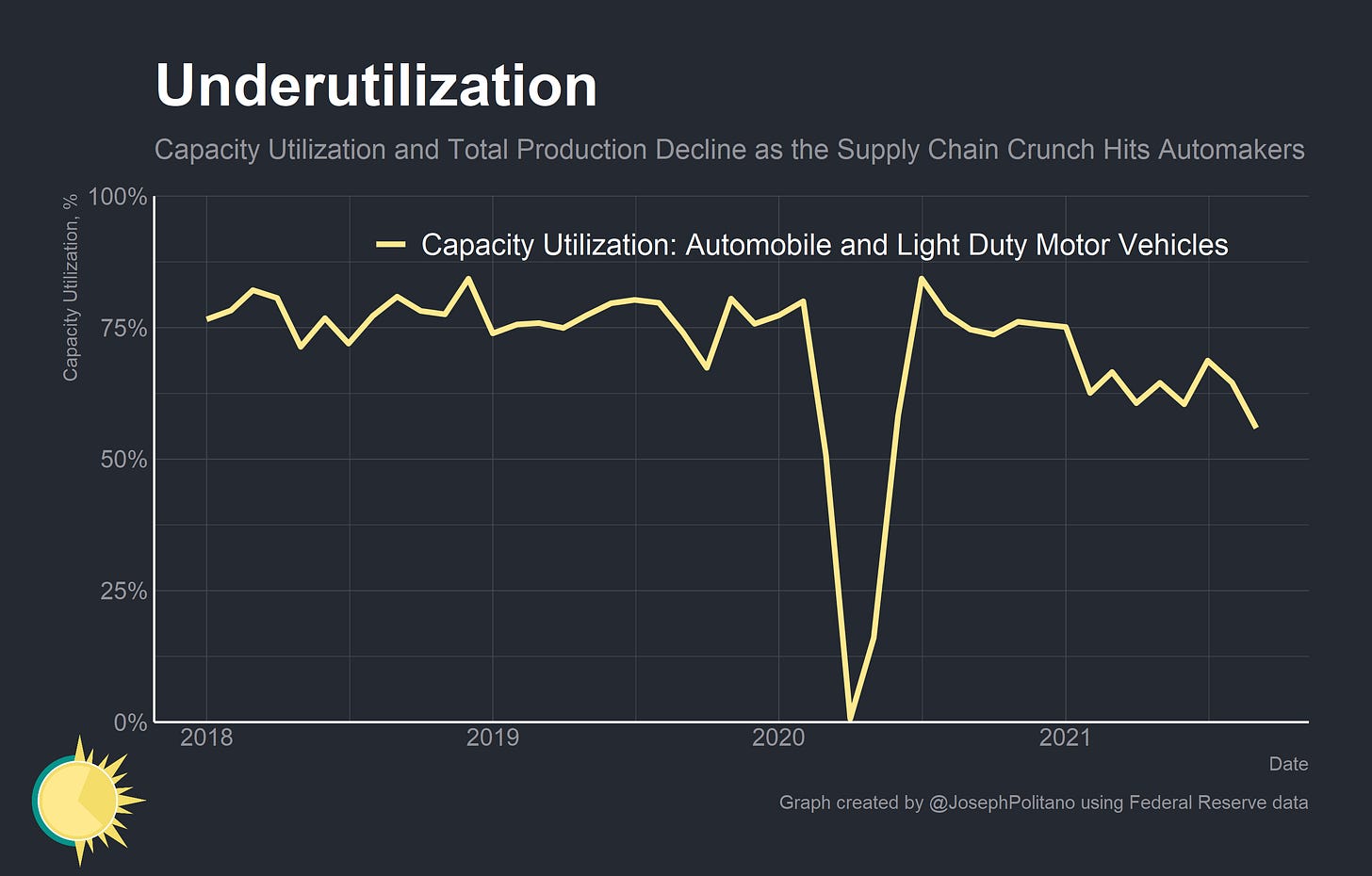

Automobile manufacturing has been on the downslide since the start of 2021 as the supply chain crisis forces firms to idle significant capacity despite an outpouring of demand. Automakers, watching the pandemic unfold before their eyes, cut back on orders for most inputs—of most critical importance, semiconductors and their associated chips—and laid off large chunks of their workforce. As a result, they were caught flat-footed by the surge in demand caused by coordinated fiscal and monetary stimulus and now are at the back of the line for semiconductor orders. The chip shortage has forced automakers like GM, Toyota, Honda, and Stellantis to completely idle US production for weeks on end. As a result, total US motor vehicle output has sunk to 2010 levels.

New car sales have tanked throughout most of 2021 and are only now picking back up. Total sales are down significantly in the light truck submarket, a category that covers SUVs, minivans, pickups, and the bulk of vehicles that Americans buy nowadays. These are are high-margin models for automobile manufacturers, so they have been prioritizing light truck production where at all possible. In addition, increased demand from families for COVID-protected personal transportation has driven light truck prices even higher—Kelley Blue Book estimates that new minivan prices were up a staggering 18% from June 2020 to June 2021.

The result of record low production and record high demand has been a rapid shrinking of car dealerships’ inventories. At the beginning of the pandemic, new car dealerships cancelled their orders and used car dealerships were flooded with inventory from the liquidation of rental car fleets. Fearful of a repeat of 2008, which forced many dealerships out of business, they circled the wagons in order to protect their balance sheets in any way possible. The resurgence in demand therefore caught dealerships off guard, leading to rapid declines in inventories across the board. Keep in mind that the graph above is in nominal numbers, meaning that the rise in prices exaggerates the real level of inventories.

It is worth noting that the structure of the US car market and the primacy of the dealership system had unique effects on auto production and sales. Throughout most of the US it is completely illegal for manufacturers to sell their vehicles directly to consumers and they are required to sell through dealerships. The result is that dealership demand—not consumer demand—determines automobile production. The distinction may seem trivial but is critical to understanding the whipsaw effects manufacturers were subjected to throughout the last two years.

At the onset of the pandemic it looked as though dealerships were about to be flooded by inventory. As mentioned before, rental car fleets were being liquidated by major companies like Hertz and Enterprise. Dealerships expected repossession rates and discontinued leases to rise as the pandemic worsened household balance sheets. Instead, the opposite happened. Rental companies scrambled to re-buy their liquidated fleets. Household balance sheets strengthened and auto loan delinquencies decreased. Repossessions declined by 30% and lease discontinuation decreased by 15%. The same dealerships that spent 2020 worried they wouldn’t be able to sell their inventory found that they were running out of inventory to sell. As of last month, dealerships were raking in record revenues and had only 2 weeks of inventory given current sales levels.

The dealership system essentially amplified both the contractionary and expansionary demand impulses of the pandemic. The result is the “bullwhip” effect where disruptions on one side of the supply chain—currently record-high demand for automobiles—are amplified through middlemen—dealerships all attempting to replenish inventories at once—before reaching manufacturers. It should be noted that the expectations of dealerships played a critical role in this process: had they expected aggregate demand to remain stable despite the pandemic they would never have cut back on their orders in the first place. Automakers would have kept their semiconductor orders, and the disruption in demand would not have been amplified into today’s shortages and price spikes.

Driving and Demanding

It is also worth exploring what, exactly, is driving the increase in car demand. Though consumers have been spending significantly more on goods of all stripes as the pandemic precludes spending on certain services, cars should theoretically be the exception to this trend. After all, a dramatic increase in work from home and a reduction in recreational travel should, all things equal, result in a reduction in automobile demand.

Instead, vehicle miles travelled (VMT), a measurement of the miles travelled by each vehicle multiplied by the total number of vehicles on the road, has practically increased back to its pre-pandemic levels. Despite the surge in goods spending, this isn’t caused by a jump in long-haul trucking. Instead, passenger VMT is running approximately 20% above pre-pandemic levels! While workers are commuting less, they are more than making up for that reduction in travel by taking significantly more trips less than three miles long. In other words, they are going on more frequent errands like grocery runs and school drop-offs in the absence of commutes.

It is worth noting the interplay between reduced public transportation usage and increased driving as a result of the pandemic. Unsurprisingly, fears of infection have lead travelers to avoid planes, trains, and buses and instead substitute these trips for additional drives. For example, daily subway trips in NYC are currently running at less than half of pre-pandemic levels, bus trips are running at 42% of usual levels, and taxi/ridehailing trips are running at slightly more than half of pre-pandemic levels. In contrast, NYC toll road traffic is running at 7-year highs. Public transportation trips are being substituted for private car trips.

Additionally, a nationwide school bus and school bus driver shortage is dramatically changing driving and vehicle purchase behavior. School bus driver employment dropped nearly 25% at the onset of the pandemic, as these workers often have precarious relationships with their employers (which are oftentimes contractors, not local governments). As demand for truck drivers surged, school districts and contractors struggled to re-hire drivers amid increased competition—causing an acute shortage. 50% of school districts consider their driver staffing issue to be “severe” or “desperate”. This is not helped by a shortage of the busses themselves; America’s largest school bus manufacturer, REV Group, reported that their “school bus business suspended production during the month of August due to lack of chassis supply.”

Demand for busses is also at an all-time high as schools attempt to spread students out and follow social distancing measures, essentially requiring more buses to transport the same amount of students. Some school districts, out of pure desperation, are paying parents to drive their kids to school instead of having them take the bus while the Governors of Massachusetts and Ohio have called upon the National Guard to fill school bus driver positions.

All this headache in the school bus system, alongside the general risk of COVID transmission on buses, has pushed many parents to drive their children to school more frequently. The result is higher traffic levels and greater demand for automobiles of all stripes, especially “family-friendly” vehicles like minivans or SUVs. It should also be noted that transportation choices are habit-forming, meaning that parents/guardians are likely to persist in driving their children to school even as COVID and the school bus shortage abate. This would means permanently elevated demand for automobiles.

Finally, the interaction between income segmentation, the transition away from public transportation, and rapid wage growth for low income workers is helping to produce rapid accelerations in used car prices. Low income workers tend to have more children and are more likely to use public transportation. As they have experienced high levels of wage growth and income support through the pandemic, many of them may be attempting to purchase used cars in order to avoid school buses and other public transportation altogether. The result is a disproportionate increase in demand for used vehicles compared to new vehicles. Since existing drivers are less willing to sell their vehicles given COVID, there are massive price increases in the used cars market.

Conclusions

It will likely take a year—if not longer—for the American automobile market to re-stabilize. There simply is not enough production capacity in the whole of North America to restore dealership inventory and satiate demand on any shorter timescale. Toyota expects it to take several months for production to reach pre-pandemic levels due to ongoing supply chain issues, though it is announcing that Japanese plants will be operating at full capacity for the first time in nearly two years. Industry leaders are warning consumers that shortages could last until 2023.

It didn’t have to be this way, though. The shortage of automobiles is a direct result of macroeconomic policy uncertainty and a half-decade of underinvestment’s effects on American vehicle manufacturing. Since 2008, automakers have scaled back investment, production, and potential output in the US as a direct result of excessively low aggregate demand. The decisionmakers who cut back on orders, reduced production, and liquidated existing fleets at the beginning of the pandemic were the same people who watched helplessly as the 2008 recession pummeled their industry. They expected a demand shortfall that never materialized thanks to successful macroeconomic stabilization from fiscal and monetary policy.

More than this, the overreliance on cars, and fuel-inefficient cars specifically, is partially a function of America’s ongoing urban planning, public transportation, and climate policy failures. Underinvestment in public transportation has made it incredibly difficult to access services without a car—even in America’s largest cities. Poor climate policy has made the country’s transportation networks extremely dependent on and sensitive to gasoline prices. In the long run, auto manufacturers’ adaptation to the COVID crisis will prove to be a dry run for the much larger sea change in the industry: the coming conversion to electric vehicles.

For America to succeed in that transition, there must be changes to the structure of the car industry. Manufacturers must be allowed to sell their vehicles directly to consumers and dealerships’ chokehold on sales must be broken. The 25% tariffs on imported light trucks must be abolished, and the network of automobile tariffs and trade restrictions should generally be trimmed down or eliminated. Investments must be made at the local level to electrify bus fleets, increase public transportation capacity, and ensure competitive wages and employment contracts for drivers. Rigorous clean energy and fuel efficiency standards should be placed on vehicles of all stripes, especially the light trucks that currently avoid regulations. The pandemic offers America the unique opportunity to be at the forefront of the next transition in the car industry, but it will require us to not repeat the mistakes that lead to today’s chaos.