The Case for a Fed "Skip"

Core Nominal Growth is Falling—and Inflation Expectations Have Normalized. That Could Lead the Fed to Hold off on a Rate Hike.

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 29,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

The Federal Reserve’s Open-Market Committee is poised to meet this week and once again decide the future path for monetary policy—but for the first time in a long time, the consensus opinion is they’ll most likely do nothing. “Skipping a rate hike at a coming meeting would allow the Committee to see more data before making decisions about the extent of additional policy firming,” said vice chair-designate Philip Jefferson, leading a chorus of members advocating for a wait-and-see approach. Right now, CME’s FedWatch tool places the market’s perceived odds of the Fed not hiking at roughly 80% based on interest rate futures pricing.

“Skips” are in vogue right now across the world’s central banks—the Bank of Canada paused its rate hike campaign at the start of this year while the Reserve Bank of Australia held rates steady in April. As banking risks remain present, inflation decelerates from record highs, and real economic growth remains subdued, monetary policymakers are starting to balance inflation risks more evenly with the other parts of their mandates—and are keen to preserve their options. In most cases, the skip approach has thus far resulted in further tightening—both the BoC and RBA resumed hikes after entering into an initial holding pattern, and Jefferson also stated that “a decision to hold our policy rate constant at a coming meeting should not be interpreted to mean that we have reached the peak rate for this cycle.” In other words, the Fed is still not confident inflation has been adequately controlled even as it holds off on raising rates for the time being.

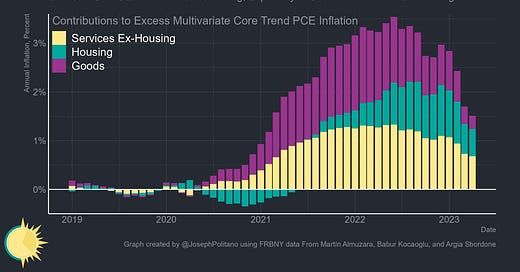

Their primary concern regarding prices is that nominal incomes and spending have remained too hot to be consistent with 2% inflation even as rates have risen dramatically and supply shocks continue fading—and those concerns are not entirely unfounded. Even as core inflation is cooling aggregate disposable income has grown by nearly 8% over the last year, buoyed in part by the effects of inflation-indexing in social security, other government benefits, and income tax rates. Nominal consumer spending has also increased 6.7% in the same time period as households spend down their excess savings, helping support today’s still-elevated inflation rates.

Yet gross labor income (GLI) growth, the sum of aggregate wages and salaries in the economy and perhaps the most important cyclical economic indicator, is steadily decelerating toward normal levels. According to recently-revised data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, private-sector wages and salaries have increased by just 5.6% over the last year, and recently-released data from the BLS’ nonfarm payrolls report shows growth decelerating to 6.2%. That isn’t total renormalization—both measures were consistently about 5% in the pre-pandemic economy—but it’s a substantial deceleration that is bringing the economy more into balance. Given labor income growth’s tight relationship with housing inflation, declining wage growth in the nonhousing services industry, and businesses’ lowered expectations for labor costs’ future contribution to inflation, the Fed should feel more confident that much of the cyclical shock to inflation looks to be fading.

Importantly, the employment sacrifices for this deceleration in income growth have been comparatively minimal—unemployment is still at 3.7% and prime-age employment rates remain at 80.7%, near the highest level since 2002. When the Fed releases its newly-revised Summary of Economic Projections this week, it will likely sound a softer and more optimistic note on the real economic outlook even as it worries about inflation. As recently as March, FOMC members expected the unemployment rate to surge to 4.5% and year-on-year GDP growth to fall to a meager 0.4% by the end of 2023—yet unemployment remains only 0.2% above March levels, and real GDP growth was already 0.3% in Q1 alone.

Medium-run market-based inflation expectations have also more than stabilized—5-year inflation breakevens have actually fallen back to some of the lowest levels since January 2021, below what would be consistent with target inflation. In fact, the skip is partially an acknowledgment that, despite a slightly lower expected path of nominal rates, monetary policy has actually firmed up a bit in the wake of Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse. Plus, it’s another way of affirming “higher for longer” interest rate policy—talk of a skip, alongside the unwinding of debt ceiling risks, has caused expected rates for the next couple of years to rise significantly over the last month. Real 5-year interest rates have risen near post-2008 highs, holding rates steady for a month still represents a tighter real policy path than in early 2023.

But mostly, the skip is a statement of uncertainty and shifting priorities in a complicated environment—the Federal Reserve is no longer single-mindedly focused on inflation, is becoming more optimistic about a soft landing, and is therefore being more cognizant of risks to growth, employment, and the financial system. Yet at the same time, it has been burned by fleeting signals of good news on inflation before and does not want to risk getting stuck with accelerating prices again. Sometimes, the best you can do is just wait.

A Deeper Look at Disinflation and Monetary Tightening

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.