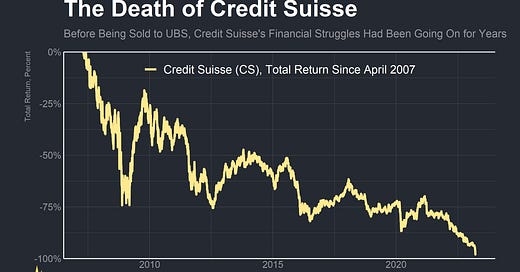

The Death of Credit Suisse

How a 166-Year Old Financial Giant Fell Apart, and What the Fallout Could Mean for the Global Financial System

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 24,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

How did you go bankrupt?

Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.

—Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises

Credit Suisse had been plagued by high-profile issues for years. It lost billions in the failure of hedge fund Achegos Capital and supply-chain financier Greensill Capital back in 2021, had data on $100B worth of accounts leaked to German newspapers in 2022, was probed by the US House of Representatives for its connections to Russian Oligarchs, and was forced to disclose “material weakness” in its financial reporting controls thanks to a last-minute call from the SEC just last week. 7% of Credit Suisse’s total revenue over the last decade went to penalties and fines, leaving the company with a net loss of $3.4B after taxes. The bank was surrounded by rumors of its impending demise for years, bleeding money and confidence while constantly scraping by through a rolling series of disasters.

Today, Credit Suisse no longer exists as an independent entity—emergency loans from the Swiss National Bank (SNB) weren’t enough to guarantee it could stay afloat, and the SNB knew that. “You will merge with UBS and announce Sunday evening before Asia opens. This is not optional,” Swiss authorities told Credit Suisse on the same day they authorized the initial emergency lending, according to reporting from the Financial Times. Faced with the risk of having to take a failing Credit Suisse under public stewardship, they decided instead to arrange a sale to the only other Swiss bank that could possibly have bought it.

This marks the first end of a Global Systemically Important Bank (G-SIB) since the category’s creation in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, and the latest in a lengthening list of bank failures across the globe—starting with Silvergate Bank last week before spreading to Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank and now ending Credit Suisse’s 166-year history as an independent institution.

In some ways, Credit Suisse’s demise is unique from the problems that plagued Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank—the institution met highly stringent European capital and liquidity standards, had been regularly supervised and stress tested over the preceding years, and had fully hedged their exposure to the interest-rate driven shifts in long-term fixed income securities prices that helped bring down SVB—distinctions that may have bought the Swiss government enough time to arrange the shotgun wedding with UBS. In other ways, their demise was much the same—like SVB, Credit Suisse was forced to watch the slow departure of wealthy customers’ funds turn into a rush for the exits as depositors reportedly withdrew tens of billions of Swiss Francs in the days before UBS’s takeover.

As often happens, a question of liquidity turned into a question of solvency—unwilling to gamble on Credit Suisse’s survival or try to manage the company’s wind-down in a public takeover, Swiss authorities agreed to a deal that gives UBS a 56B Franc discount to the book value of the company’s assets and an additional 9B Francs in guarantees from the government in the event of certain losses. 16B Swiss Francs in Credit Suisse’s Additional Tier 1 Capital Bonds—debt liabilities designed to absorb losses in the event of trouble—were zeroed out, and an emergency ordinance from the Swiss Federal Council stripped both company’s shareholders of the ability to vote down the deal.

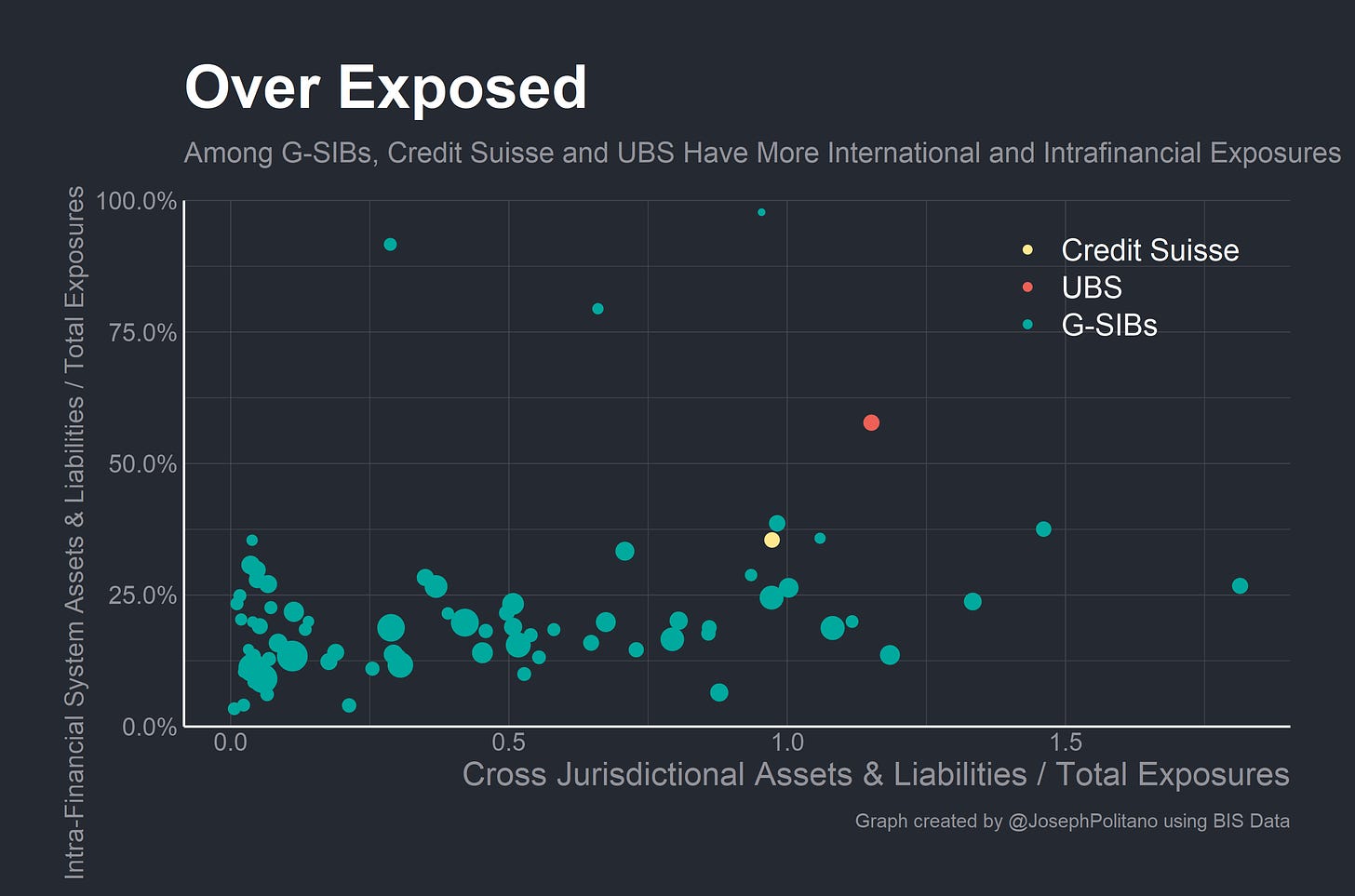

Central banks across the world are taking steps to ensure CS’s failure doesn’t mutate further into a global financial crisis—European and American agency heads were closely watching the situation, the SNB extended fresh liquidity to the new UBS/CS merger, and six major central banks put out a joint statement expanding the ability of foreign central banks to access dollar liquidity from the Federal Reserve. The Swiss banking system’s disproportionately large and complex international financial relationships mean Credit Suisse’s fall is likely to have aftershocks throughout the broader financial system—but understanding those requires first looking at the roots of what brought down the financial giant in the first place.

Debit Suisse

Credit Suisse’s financial troubles have been going on for years but became critical recently, with the company failing to break even in any of the last five quarters. In early 2021 it lost $5.5B to the collapse of Archegos Capital Management, a family office that had borrowed billions to make stock market bets that fell apart. Several major investment banks had lent to Archegos, but Credit Suisse’s losses exceeded those of all other investment banks combined thanks to the firm’s poor risk management and slow response. Indeed, it was precisely Credit Suisse’s vaunted investment banking division that was responsible for most of the company’s recent unprofitability, losing 3.4B Francs in 2021 and 3.1B Francs in 2022.

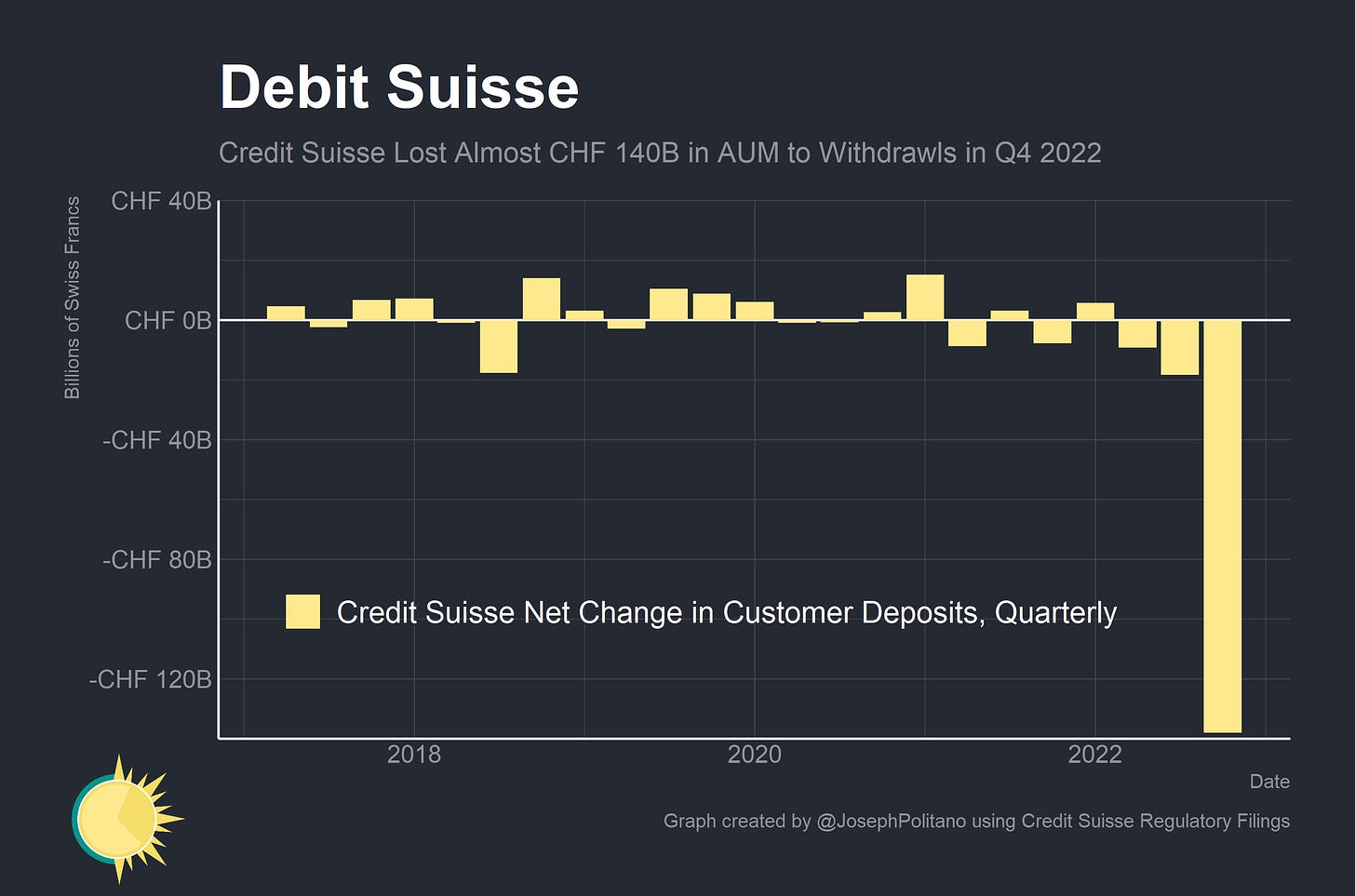

The surge in bad press and ongoing concerns about the company’s financial health led customers to head for the exits even before the death of Silicon Valley Bank. In Q4 2022, Credit Suisse lost nearly 140B Francs in deposits to a rush of withdrawals that began in October, meaning the bank had lost more than 40% of total deposits since the first quarter of 2021. Customers were reportedly withdrawing even more funds in the days leading up to UBS’s takeover—the numbers vary depending on the source, but it was 35B Francs in just 3 days according to the Financial Times’ reporting.

A large chunk of those withdrawals came from Credit Suisse’s large foreign depositor base—foreign deposits at large Swiss Banks fell by 58B Francs over the 9 months ending in January 2023, and total dollar deposits fell by 45B over the same time period.

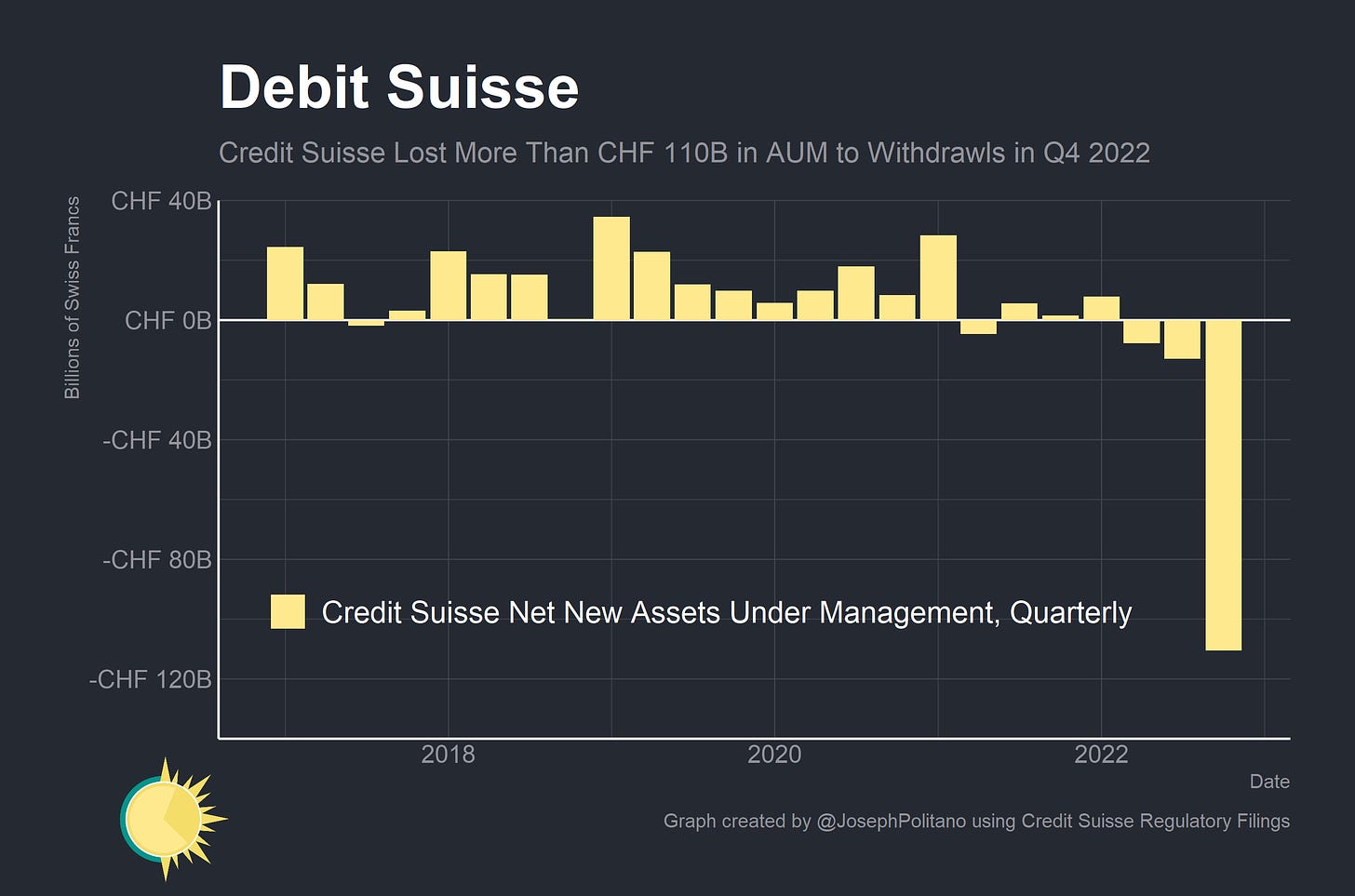

The bank’s wealthy clients weren’t just pulling out their deposits either, they were taking out all their assets at once. Credit Suisse saw 110B Francs in net withdraws of assets under management in Q4, led by a 93B Franc reduction in new assets under the wealth management division (a 15% drop). In other words, the disproportionately wealthy and foreign customers that made up a large part of Credit Suisse’s clientele were already leaving months ago, and bank executives and regulators saw that process accelerate in recent weeks.

Credit Suisse may have been solvent and liquid, but there is a critical mass of deposit outflows that will kill any financial institution, and authorities concluded that the chances of Credit Suisse facing such outflows if allowed to remain open were too high. The bank’s clientele was unusually flighty for a large institution, spooked by recent events, and had low levels of confidence in Credit Suisse’s ability to successfully continue operating. A public wind-down would mean disentangling a major institution into an already-worried market at significant public cost and would permanently impair the international image of Swiss Banking under the best-case scenario, so the government decided to preemptively sell Credit Suisse in order to avoid the growing risk of disaster.

Picking Up the Pieces

So what happens in the fallout of CS’s demise? Among all Global Systemically Important Banks, CS and UBS were unique for two things: their cross-jurisdictional exposures, thanks to the outsized prominence of Swiss banking in international finance, and their intra-financial system exposures, thanks to the unique nature of the two banks—in short, both Credit Suisse and UBS had prominent relationships with non-Swiss customers and had deep ties to other parts of the global financial system. The risks inherent to those exposures are partly why Swiss regulators decided to force a sale of Credit Suisse before it could collapse, but even a more orderly resolution under UBS could still pose risks to the broader financial system.

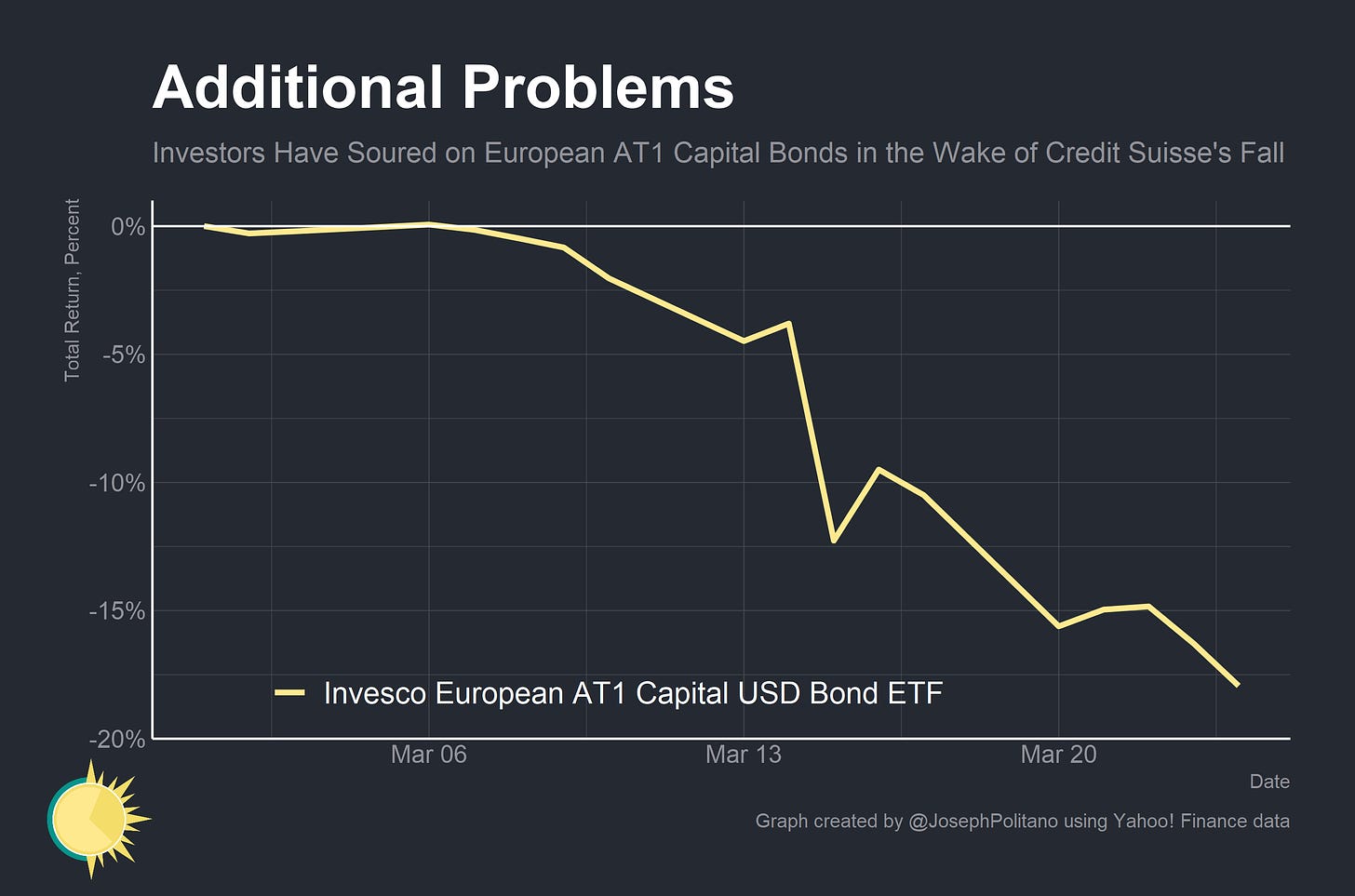

Regardless of the potential for direct contagion, the demise of Credit Suisse is likely to shake confidence in other lenders, especially in Europe. In particular, prices for European Additional Tier 1 (AT1) Capital Bonds—debt instruments that usually convert to stock if the bank encounters stress and falls below predetermined capital ratios—have fallen dramatically over the last few weeks. Credit Suisse’s AT1 holders were given nothing in the UBS takeover despite the fact that shareholders got a small payout—which is exactly how Credit Suisse’s specific AT1s were designed, but is highly unusual among the broader AT1 market and not something many investors had evidently appreciated. Other monetary authorities—including the European Central Bank, Bank of England, and Monetary Authority of Singapore—rushed to state that shareholders would absorb losses before AT1 holders under their bank resolution frameworks, but it hasn’t yet been enough to rebuild sentiment for the assets. On net, that will make it harder for European banks to raise money precisely when they may need it most.

Federal Reserve lending via the Foreign and International Monetary Authorities (FIMA) repo facility also shot up to $60B this Wednesday—meaning some foreign central bank (or banks) borrowed a significant amount of dollars from the Fed by pledging US treasury bonds as collateral. That borrowing is suspicious for several reasons—For one, $60B is exactly the per-counterparty limit on FIMA borrowing, implying that one institution likely maxed out its credit line. For two, the rates for FIMA repo borrowing are significantly above market repo rates, implying that some foreign central bank was unwilling or unable to borrow from the open market.

The most likely candidate is, by far, the Swiss National Bank—they have large amounts of dollar-denominated foreign exchange reserves to borrow against and CS/UBS likely needed some dollar liquidity—but using FIMA Repo instead of the open market implies they were willing to pay a premium to conceal their borrowing or felt they could not access the normal repo market. It would also be weird for the SNB to max out their $60B line from the FIMA repo facility without borrowing any significant amount from the Fed via central bank liquidity swaps (where the SNB would essentially only have to post Francs as collateral instead of Treasuries). Although liquidity swaps would have been more expensive than FIMA repo through Wednesday thanks to a quirk in their pricing structures, they are still fairly generous deals only currently available to a select few major central banks—and the SNB had only borrowed $100M through them as of Wednesday.

Containing the Fallout

A worrying possibility is that the FIMA borrowing isn’t the SNB, but rather a stressed non-US financial institution turning to their central bank for dollar liquidity, who in turn felt the need to borrow from the Fed. Though much less likely, Hong Kong, China, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates are other possible contenders for the mystery FIMA repo user(s) as they are countries with disproportionate exposure to Credit Suisse, have enough Treasuries to post as collateral, do not have access to swap lines, and might have had financial institutions with a need for dollar liquidity.

It’s impossible to do anything except speculate on who the true borrower is for now, but it’s clear that global central banks are still working to contain the fallout of Credit Suisse’s demise and the ongoing banking system stresses. The SNB has set up 200B Swiss Francs of emergency credit lines for the new UBS/CS merger, the Fed is now lending more than $350B to the US banking system, and the European Central Bank is checking lenders for indirect exposures to Credit Suisse’s collapse. Share prices for major European banks—most notably German Deutsche Bank but also French lenders Société Générale and BNP Paribas, Dutch ING Group, and British Standard Chartered, among others—have tumbled over the last month as the banking system weakened, a trend that has only accelerated since Credit Suisse’s fall.

For the time being, policymakers project confidence that their efforts to shore up liquidity have managed the immediate crisis—the European Central Bank and the Swiss National Bank just raised rates by 0.5% and Federal Reserve raised rates by 0.25%, all of whom cited inflation risks as being still more important than financial stability risks. This is not to say that financial stability risks have disappeared; on the contrary, they continue to reverberate throughout the global economy—and the recent failures of SVB, Signature, and Credit Suisse are a reminder that risks can move at a breakneck pace in today’s modern world.

Great read, and appreciated the speculation around FIMA borrowing.

Not too long ago, CS's investment bank was considered with pretty high esteem here in the US - less prestigious than GS, MS or JPM, but a very solid middle-of-the-pack bulge bracket bank, and probably better than DB/Barclays/UBS/Bofa. Its been interesting to watch their reputation fall along with each blunder over the past five or six years.

Crazy times we’re living in