The Death of First Republic?

Rumors of an Imminent FDIC Takeover Circle America's 14th-largest Bank. Can it Survive?

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 27,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

First Republic is in crisis—in the seven weeks since Silicon Valley Bank’s failure it has struggled to fend off a bank run of its own. Uninsured deposits, which made up more than two-thirds of the bank’s deposit base at the start of the year, began fleeing en-masse after SVB’s collapse, and the company has had to take drastic measures to stay afloat. It borrowed billions from JP Morgan Chase, the Federal Home Loan Banks, and the Federal Reserve while receiving a $30B deposit infusion from a consortium of major US banks. The company’s valuation has fallen a staggering 97% over the last two months, and 75% over the last week alone. On the bank’s earnings call this Monday, management refused to take any questions. By Friday, Reuters reported that the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was looking to take over First Republic “imminently”.

If that happens it would be the 2nd largest bank failure in US history—the institution’s total assets are $230B, larger than Silicon Valley Bank’s before its failure—and the latest in a string of financial panics that have already claimed three major financial institutions across the globe. In many ways, First Republic’s problems look like a slower-moving version of the problems that plagued those three institutions—like Signature Bank and SVB, it had an unusually high share of uninsured deposits for a regional bank, like Credit Suisse it had seen significant deposit flight from its wealthy clientele, and like SVB it had invested heavily into longer-maturity low-yield assets that declined in value as interest rates rose. Yet First Republic was in a better position than most of these institutions—though a Bay area bank, it was much more diversified across industries and geographies, though it catered to a high-net-worth clientele it was not exclusively a bank for the superrich, though it had seen substantial deposit growth with the tech boom it had not felt effects from the tech-cession, and though it did end up heavily concentrated in low-yield long-dated assets those mostly represented traditional mortgage lending. Those differences, however, may not be enough to save it from failure—an indication that the creeping banking crisis is affecting a broader swathe of the financial system.

First Republic

When Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank collapsed, it was partially because a critical mass of uninsured deposits—those in accounts exceeding the FDIC's $250k insurance limit—decided to transfer or withdraw their money in light of the banks' rising failure risk. In both banks’ cases, more than 90% of deposits were uninsured and the depositor bases were mostly geographically and sectorally concentrated businesses.

In First Republic's case, uninsured depositors only made up roughly 67% of total deposits, higher than at most banks but lower than at Signature and SVB. A bank run where a critical mass of depositors withdraw their funds would have required virtually all uninsured deposits to leave—which is by and large exactly what happened. At the start of the year, First Republic had $118.8B in uninsured deposits. By March 31st, they had only $19.8B after excluding the deposit infusion from other major banks—$100B in total had been withdrawn in just three months, and it’s most likely that the vast majority of withdrawals occurred in March with further withdrawals occurring since then.

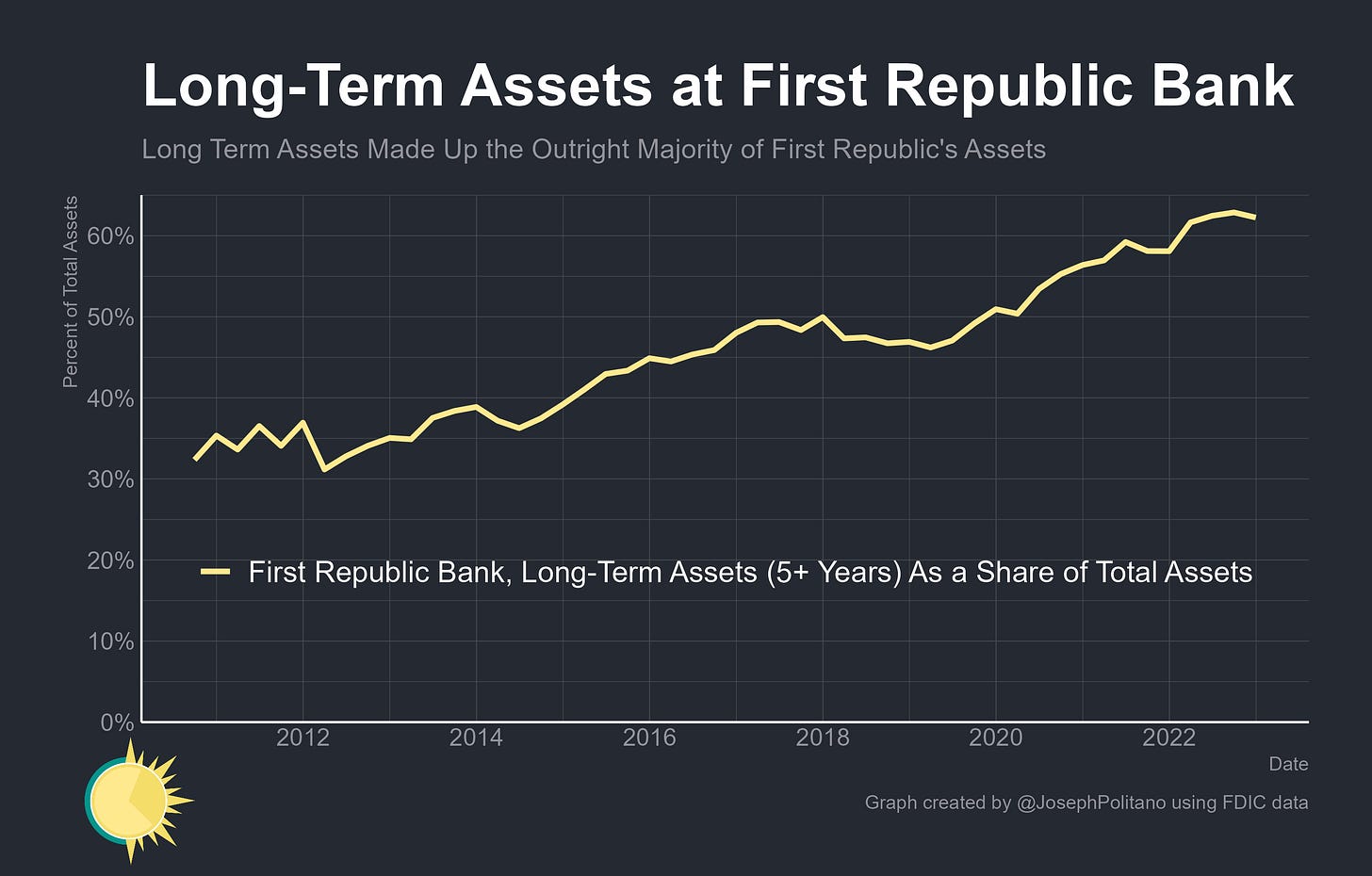

Just like Silicon Valley Bank, First Republic concentrated further into long-duration assets when their yields were low in 2020 and 2021. In fact, the share of total assets composed of loans or bonds with a maturity of 5 years or more was higher at First Republic than SVB, though more of First Republic’s investments predated the pandemic.

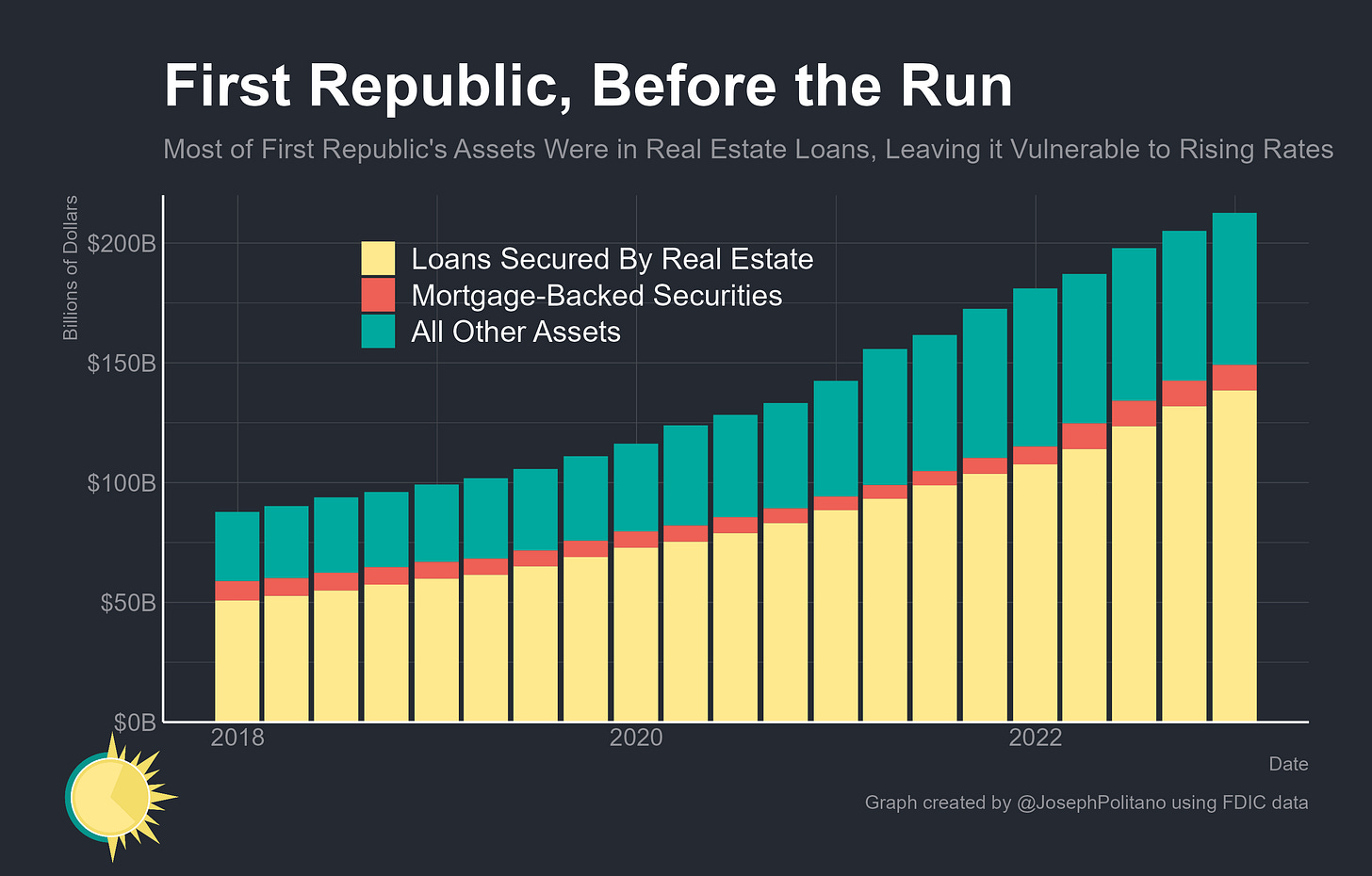

However, unlike Silicon Valley Bank those long-term assets primarily represented normal real estate loans rather than debt securities. First Republic’s real estate loans increased significantly throughout the pandemic, from $72B at the beginning of 2020 to $138B by the end of 2022.

So First Republic management had invested significantly in longer-term Treasury bonds and other securities at low yields—and watched the value of those higher-duration assets plummet as interest rates rose throughout 2022. The gap between the accounting and fair value for First Republic's mortgage assets approached $20B—14% of the total accounting value—at the beginning of the year.

When depositors started fleeing, First Republic had to find other sources of funding—which it did mostly by borrowing more than $100B from various sources. Those loans came partly from the Federal Home Loan Banks, lenders of next-to-last-resort that First Republic had used consistently even before the crisis, but also from a line of credit with JPMorgan Chase and directly from Federal Reserve's Discount Window. The principal problem is that those sources of funding are extremely expensive—practically ruinously so, compared to First Republic's prior deposit funding base. The interest rate on First Republic's discount window loans is currently a painful 5%, far exceeding the 3.18% average yield on First Republic's real estate loan portfolio. It's another reminder of how interconnected illiquidity and insolvency are—if First Republic had kept its deposit franchise it may have been able to limp along, but with that gone the bank's profitability and long-term solvency come into question.

So what can save First Republic? The situation appears pretty dire—few financial institutions have bounced back after rumors of a government takeover have gotten this loud. Although there are only $19.8B in uninsured deposits that could run (if you exclude the deposits of other major banks), that alone would cost hundreds of millions a year in extra interest expenses if it was replaced by more borrowing. Insured deposits might start leaving too if people simply elect to close their accounts or want to avoid the possible inconvenience of dealing with the FDIC's recovery process.

Auctioning off assets at fire sale prices would incur significant losses for the bank, so most speculation around a private sector solution comes in the form of buying out assets at higher prices in exchange for equity in First Republic, a tough deal to manage. The government might try to arrange a shotgun marriage by offering some federal assistance, credit, or guarantees to smooth over a sale to another institution—PNC and JP Morgan Chase are rumored to be interested in buying the firm out of FDIC receivership. Or Federal Reserve lending terms might be eased to keep First Republic alive a little longer. The bank can't borrow much from the Fed's new Bank Term Funding Program, which offers loans up to one year long against collateral valued at par, because it has little of the high-quality securities eligible for the facility. The Fed might expand BTFP eligibility to include more asset types, it might increase the length of discount window loans as it did at the onset of COVID, or find some other way to make First Republic's funding problems less onerous in order to buy more time.

The US Banking System is Still Stressed

When Silicon Valley and Signature Bank failed, it was possible to pin the crisis mostly on the unique profile and decisions of a couple of extremely unique banks—most financial institutions were not so dependent on flighty, concentrated deposits or had lost so much on their assets as interest rates rose. Credit Suisse’s failure was less unique but still represented the collapse of an institution that had fundamental flaws for more than a decade. First Republic is much more of a normal bank than any of those institutions—and its failure indicates how much stress is still pervading the US banking system.

Domestic deposits have been sliding as the Fed’s higher rates and quantitative tightening pass through to banks, with deposits at small domestic banks falling dramatically in the wake of SVB’s collapse. Most of the deposit losses have been in major US banks—but that includes “regional” banks like First Republic and SVB alongside the giants like JPMorgan Chase or Bank of America.

Most of the deposit losses in the banking system have been concentrated in savings and non-demand deposits. The amount parked in savings accounts, money market deposit accounts, and other non-demand-deposit accounts has fallen nearly $2T since the start of 2022, with money moving into higher-rate CDs and time deposits and leaving the banking system entirely for retail money market funds.

In the place of those deposits, banks are borrowing a massive amount to cover their funding needs—aggregate borrowings have risen more than $400B since March 1st and borrowings from the Federal Home Loan Banks have now exceeded $1T for the first time since the Great Recession.

Meanwhile, direct lending to the banking system from the Federal Reserve remains elevated. Although discount window lending has tapered off slightly in the weeks since SVB’s collapse, aggregate usage remains much higher than at the start of the year. Banks are continuing to use the BTFP to refinance against their long-term assets, and lending to the FDIC bridge banks for SVB and Signature remains extremely high. All that borrowing is better than if the Fed left the banking system without help—but it means higher funding costs for the banking system and reflects the broadening nature of financial risks.

The Unfortunate Interest Rate Channel

Fundamentally, the business of a bank requires borrowing short-term (via deposits) and loaning long-term. That business model becomes more difficult when the yield curve is inverted and short-term rates are higher than long-term rates. Inflation, tightening monetary policy, and recession risks have caused the yield curve to invert to an extreme degree that it is making the business of banking harder—especially when rates have risen so rapidly in such a short period of time. Indeed, giving banks and other financial institutions time to adjust is the primary justification for raising rates incrementally instead of all at once, and the rapid pace of hikes and the Fed’s decision to raise rates again in the wake of SVB’s collapse worsened First Republic’s chances of survival.

Still, arguably the biggest change within the banking system has been to depositor dynamics. Usually, rising rates should help banks as yields on assets rise faster than the interest paid on deposits—but that relies on depositors being mostly stable, sleepy users who don’t move their assets rapidly to chase yield or flee if the bank looks to be in trouble. Rich depositors with uninsured accounts were sleepy giants—and those giants have awoken, to the detriment of First Republic and the other banks that depended on them.

Terrific review of banks, banking business and how easily things can roll off of a cliff. Thanks Joseph for wonderful insight into this.

The only question is what will be the next domino.