The Death of Silicon Valley Bank

What We Know So Far about The Second-Biggest Bank Failure in American History

Three months ago, Silicon Valley Bank was the 16th-largest commercial bank in the US.

Today it no longer exists.

On March 8th, Silvergate—a smaller bank specializing in the crypto business—announced it would be voluntarily liquidating in the wake of large losses, rapid customer withdrawals, a Department of Justice probe, and a worsening crypto market. That same day, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) announced that it had sold significant amounts of US Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities at a $1.8B loss and would be raising more than $2.25B in capital to strengthen its balance sheet. On March 9th, customers rushed to the bank and withdrew $42 Billion in deposits—more than 1/4 of the bank’s total. SVB couldn’t even make it to the end of the week—Friday morning, California and Federal regulators shut down the bank citing both illiquidity and insolvency.

In the wake of the second-largest bank failure in American history, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) has stepped in to place Silicon Valley Bank into receivership. In its place, the FDIC will open the Deposit Insurance National Bank of Santa Clara on Monday to return funds to insured depositors. The catch is in SVB’s unique clientele—being mostly a bank for tech companies, venture capital firms, and high-net-worth individuals, vanishingly few of its customers’ account balances fall under the $250,000 limit of FDIC insurance. As of the start of the year, less than 6% of its total deposits were covered by FDIC insurance.

Indeed, it was its unique customer base that ultimately helped kill the bank—SVB saw massive deposit growth in the early pandemic as the silicon valley venture capital industry boomed, with total deposits peaking at more than quadruple early 2018 levels. They decided to match that deposit growth largely with aggressive, seemingly largely unhedged, purchases of long-maturity US Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities—assets that took a big plunge in price when the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates. Tighter monetary policy also damaged the bank’s tech industry clientele—SVB estimated that it was losing an average of $14.5B a quarter in total client funds over the last year thanks to a big fall in VC funding and elevated cash burn among tech companies. Higher rates squeezed the bank’s assets while causing big deposit outflows—a deadly combination.

The end result is that the bank was likely, mark to market, insolvent by the start of the year. That’s not necessarily a death sentence—banks don’t have to mark all their assets to market for a reason, and with more time, SVB might have raised enough money, earned enough profit, seen its assets appreciate, or some combination thereof to stay operational. But when a critical mass of depositors noticed that the bank wasn’t in ideal financial shape, that their money was largely uninsured, and that other people were already thinking about leaving, the incentive became to be the first ones out the door. Of course, having a fairly sophisticated, centralized, undiversified deposit base did not help—once major venture capital players started telling their portfolio companies to withdraw their money word spread like wildfire and everybody just started swarming the exits.

On Thursday, former SVB CEO Greg Becker asked clients to stay calm and support the bank the way it had supported them over the years. By then it was already too late—trust was completely gone. Enormous outflows of deposits forced SVB to realize massive losses, and the bank would be in receivership the next day. To fully understand how this happened, we have to first look at those years when SVB was still riding high as the premier bank of the VC industry.

SVB Before the Run

SVB always had a comparatively low share of insured deposits—a consequence of being more business-focused and catering towards one of the wealthiest industries in the world—but after the 2020/2021 VC boom the share of deposits with FDIC insurance dipped from just below 9% to just above 4%. More than 37 thousand separate SVB accounts exceeded the $250,000 FDIC insurance limit at the end of 2022, and the average customer balance was $4.2 million.

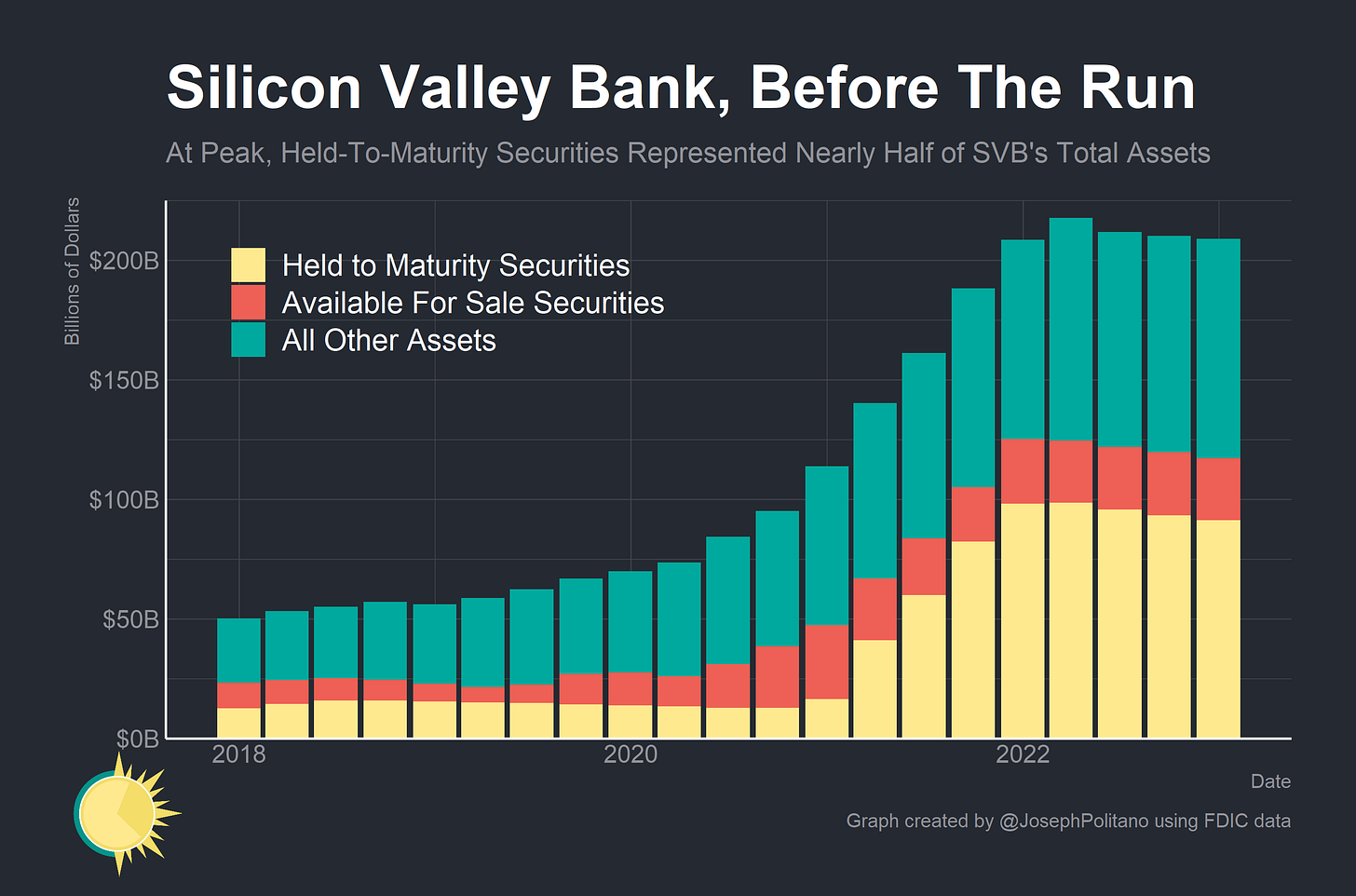

As that pile of money increased and the bank grew, a larger share of SVB’s assets ended up going to long-term loans and securities, especially during the tech-boom-driven surge. By late 2021 an outright majority of the bank’s assets were maturing in 5 or more years and, at peak, long-term assets made up more than 55% of total assets, up from just under 35% before the pandemic. SVB in many ways made a big directional bet on interest rates—buying long-term assets when yields were very low—and it did not pay off for them. The securities sold at steep losses this Wednesday had a yield of 1.79% and a 3.6-year duration—for context, 2-year Treasury yields topped 5% the day SVB made the sale.

SVB essentially ended up with a really brutal duration mismatch problem—they had bought a lot of long-term high-quality securities with very low yields, and rising interest rates meant the market value of those securities had plummeted. The solution was to decide to categorize those securities as “held to maturity”—essentially agreeing to hold the assets until their full repayment in exchange for not having to mark them to market—in contrast to securities listed as “available for sale,” which can be sold more readily but must constantly be marked to market. On a long enough timescale, this would hopefully work out—if you buy a Treasury bond paying 2% interest you will always eventually get your 2% interest and principal regardless of its current fair market value—but what made SVB special was that so much of their assets had to be held to maturity—at peak, nearly half of SVB’s assets were held-to-maturity securities.

As interest rates continued to rise, SVB started suffering deep unrealized losses on much of its securities portfolio. Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income (AOCI)—which incorporates unrealized gains/losses in the securities classified as available-for-sale, sunk to more than negative $2B at its peak and remained deeply negative at the most recent regulatory filing at the end of 2022.

But that likely pales in comparison to the unrealized losses on SVB’s held-to-maturity securities. As of the end of 2022, the fair market value of the bank’s total held-to-maturity securities portfolio was more than $15B smaller than the assets’ amortized value, a number that had only grown larger and larger as interest rates increased. These reflect substantial unrealized losses for a bank SVB’s size and were a large part of the reason doubts grew about the bank’s financial stability. Again, this is a painful but theoretically fixable problem provided enough time and a lack of deposit flight—but those were luxuries SVB did not have.

The Solvency-Liquidity Problem

Indeed, SVB was facing short-term funding issues in addition to the long-term solvency problem—as of the end of 2022, more than 25% of the bank’s securities portfolio was already pledged as collateral to secure short-term loans—and it is possible SVB was forced to pledge even more in the intervening months.

SVB was also borrowing a large amount from the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs), government-sponsored member-owned banks that offer liquidity through secured loans. In fact, as of Q3 SVB alone was responsible for 20% of FHLB San Francisco’s loans outstanding. Banks don’t normally tap the FHLBs in that quantity unless they feel they really have to, so SVB was likely under a lot of funding stress.

There’s a natural tendency to want to classify financial collapses as either liquidity issues or solvency issues—in a liquidity crisis, an institution that ultimately has more assets than liabilities isn’t able to come up with enough cash to meet short-term obligations, in a solvency crisis an institution fundamentally doesn’t have enough total assets to meet total liabilities and has no way to make up the difference. But it’s not actually that black and white—solvency issues become liquidity issues and vice-versa. The lingering solvency question caused the liquidity issue at SVB at the same time the liquidity crunch forced them to realize losses that made them insolvent—SVB was a liquid, solvent institution last week and today it is neither.

What Happens Next?

So what’s next? Since the failure of IndyMac in 2008, where uninsured customers received 50 cents on the dollar for their deposits, it’s been unofficial US policy that regulators come up with a plan to make all depositors whole—whether that’s achieved by selling the bank entirely to a bigger company, selling off the remaining assets of the failed bank piecemeal, or through more direct means. The logic is that even most sophisticated depositors can’t (or functionally don’t) readily assess the health of their banks and that a failure would lead to financial instability as, among other things, uninsured depositors flee any other institutions rightly or wrongly seen as at risk. And if uninsured SVB depositors get back only a fraction of their total assets it could represent a massive net loss—even under an unrealistically optimistic scenario in which all withdrawals on March 9th were processed and only uninsured deposits were withdrawn the vast, vast majority of SVB’s remaining deposit liabilities would still be uninsured.

Usually, the most likely outcome in cases like this is a buyout from a larger institution—a more stable bank should be able to profit by holding the held-to-maturity securities until, well, maturity, and the relationships SVB has built up with some of the largest VC and tech firms on the planet likely make the company’s remains more enticing than most failed financial institutions. Still, no buyer stepped up on Friday, either because of the rapid speed of the collapse, fear of catching an unknown hot potato, or simply a desire to get a better price later down the road.

Uninsured SVB depositors are scheduled to receive an advance dividend—a possibly partial repayment of their deposits based on the FDIC’s assessment of the bank’s assets—sometime next week. Since much of SVBs assets were in high-quality liquid securities (even if they had large unrealized losses) it should hopefully be relatively easy to get some payout to uninsured depositors, although it’s impossible to say anything definitive without first getting the FDIC’s assessment of what remains of the bank’s assets—it’s still far too early to know anything with great certainty.

Contagion and Risk

The primary concern with any financial failure is contagion—the idea that cross-institution linkages, generalized fear, or cyclical macroeconomic factors could drive more banks or other institutions into distress and create a broader doom loop within the economy. One way where today, so far, still looks different than 2008 contagion is credit risk—broadly speaking, charge-off and past-due rates for loans remain at or near secular lows, though they have been trending up recently. In other words, there has not yet been a substantial rise in defaults on banks’ assets.

However, duration risk is a more widespread problem—SVB’s assets were extremely concentrated in long-term securities, its deposit base was unusually undiversified, and it lost comparatively more money than most, but it is true that a lot of US banks have significant mark-to-market losses and have been increasing their proportional investment in held-to-maturity securities for years. If SVB’s situation ends badly a lot of regional banks could face the same kind of massive outflows from uninsured depositors that SVB did.

Indeed, the tighter monetary policy environment and shrinking of the Fed’s balance sheet are partially designed to create the kind of competition for scarce funding that can pose a serious threat to commercial banks. Deposit rates are slowly rising, aggregate US bank deposits are falling, commercial banks are seeking out more expensive sources of funding, and SVB is not the only one in the unenviable position of having fixed-rate assets that have fallen in value against floating-rate liabilities that have gotten more scarce. A large majority of US banks are continuing to tighten their credit standards and are bracing for what they expect to be an upcoming economic downturn. So system-wide financial risk has been elevated—even before SVB’s failure.

Move Fast and Break Things

Broadly speaking, today’s central banks face a tradeoff between inflation fighting and financial stability—rapid rate hikes are more likely to tame inflation faster but increase the risk of running into unforeseen financial crises. Raising rates slower and more predictably will lower the risk of financial problems, but increase the risk of elevated and harder-to-tame inflation. The Fed, along with most central banks across the world, has adopted at least one Silicon Valley aphorism—“move fast and break things”—they’ve been increasing interest rates quickly knowing it will worsen financial conditions because they believe it’s necessary to get inflation under control.

In a way, SVB’s blowup is a larger-scale version of the liability-driven investment blowup that wreaked havoc in the UK six months ago—in both cases, rapid rate hikes exposed a financial vulnerability in an unforeseen sector that impaired the basic functioning of markets and required a temporary reassessment of monetary policy strategy as the situation unfolded. In the UK, the crisis passed by without much lasting damage—although SVB is certainly a larger failure, only time will tell how much it means to the broader US economy.

At the very least, this is going to be another hit on America’s already embattled tech sector—after years of stable and relatively constant growth, we are possibly seeing the first declines in tech employment since the Great Recession. For the industry, SVB’s death in the best-case scenario represents the loss of one of the few highly specialized major tech-related financial institutions—and it might still end up being a major financial hit for the 50% of US VC-backed tech companies that banked with SVB—along with their workers, families, businesses in supporting industries, and the California economy. Contagion isn’t just a thing that happens to banks.

> As of the end of 2023

Guessing this should say 2022?

Excellent analysis