The Economic Fallout of Student Loan Forbearance Ending

Restarting Student Loan Payments Has Led to Higher Delinquencies and Lower Consumer Spending—Though Impacts Have Been Heavily Mitigated by Debt Relief

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 37,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

This October, for the first time in more than 3 years, Americans were once again required to make payments on their $1.5T of outstanding Federal student debt. The loans had been in forbearance for years, with no money due and no interest accruing throughout the pandemic, but a Congressional debt ceiling agreement at the end of last Spring had finally mandated that payments resume this Fall. On top of that, the Supreme Court then struck down a plan by the Biden administration to forgive at least $10k for most borrowers, precluding any chance of universal debt relief for the time being.

With forbearance ending, Americans have unsurprisingly begun repaying their student loans en masse over the last few months. Starting in August, payments to the US Department of Education, most of which represent student loans, surged back to about their pre-pandemic rate of more than $75B annualized, up from the extreme lows of less than $13B annualized seen just months prior. Payment flows have declined a bit since then, with the 22% drop between October and November suggesting that some of that initial spike represented a subset of borrowers strategically paying off their remaining debt in bulk when forgiveness was taken off the table, but they still remain well above pandemic-era levels.

Now that households are making student loan payments once again, what does it mean for the broader economy? The restart has been a drag on Americans’ household finances, helping drive up expenses when many are already stretched thin by the inflation of the last few years. That’s led to rising delinquency rates and forced those with substantial student debt to cut back on their discretionary spending. Yet at the same time, the burden is much smaller than it was pre-COVID thanks to reforms to income-driven repayment plans, a generous on-ramp plan that is not punishing borrowers who miss payments until September 2024, and forgiveness of billions in student debt even outside the plan struck down by the Supreme Court. The overall economic impact has been noticeable, but relatively modest—although the student loan restart is only a small part of the recent economic headwinds from the rising cost of consumer debt.

The Cost of the Student Loan Restart

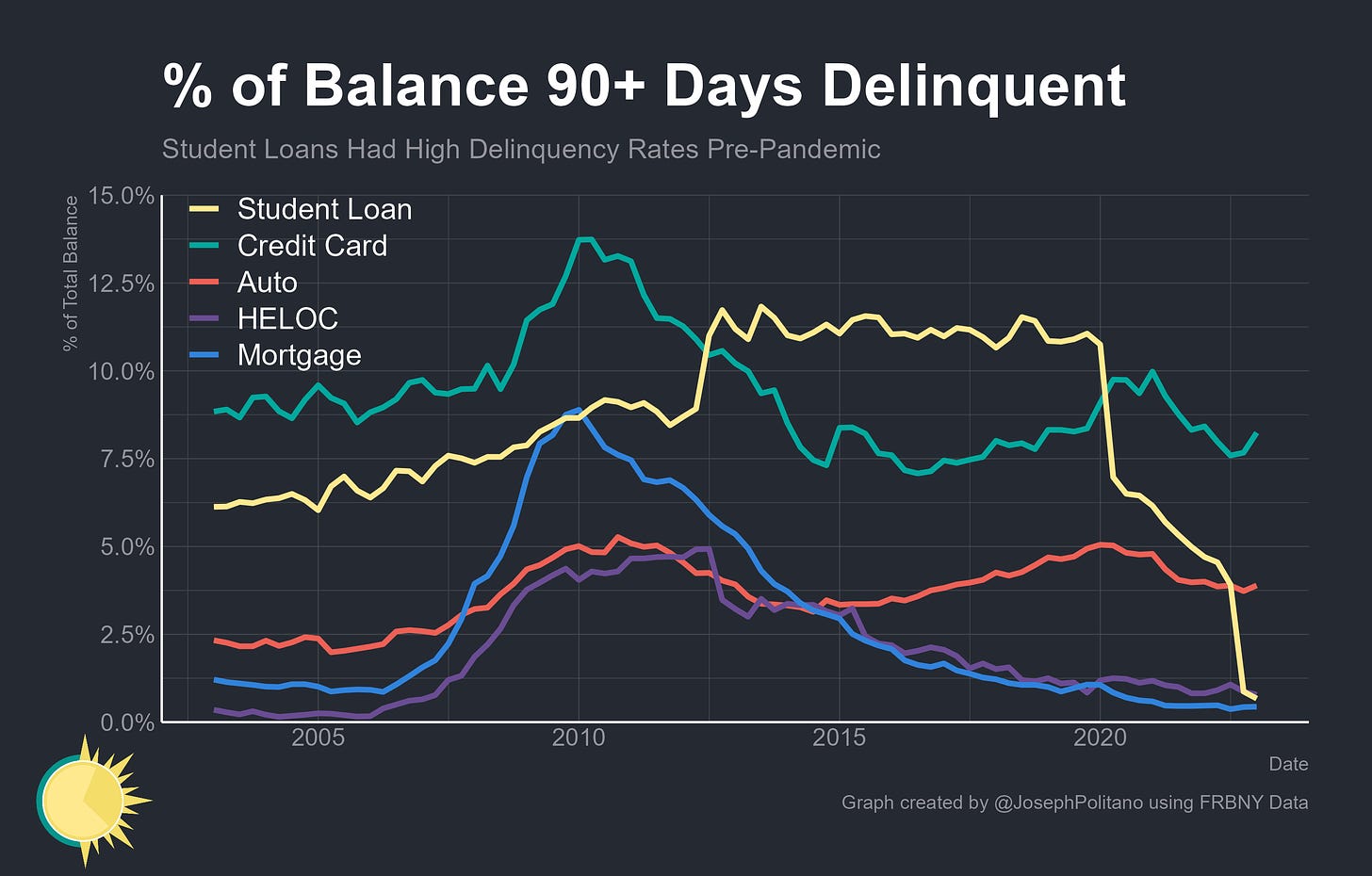

Pre-COVID, student loan debt was by far the most likely category to fall into delinquency. The consequences were minimal compared to having your car towed or home repossessed, and the debtors were disproportionately early-career workers with low net worths. During the pandemic, forbearance policies naturally sent student loan delinquency rates to extremely low levels and kept them there even as credit card and auto delinquency rates began gradually increasing over the last year.

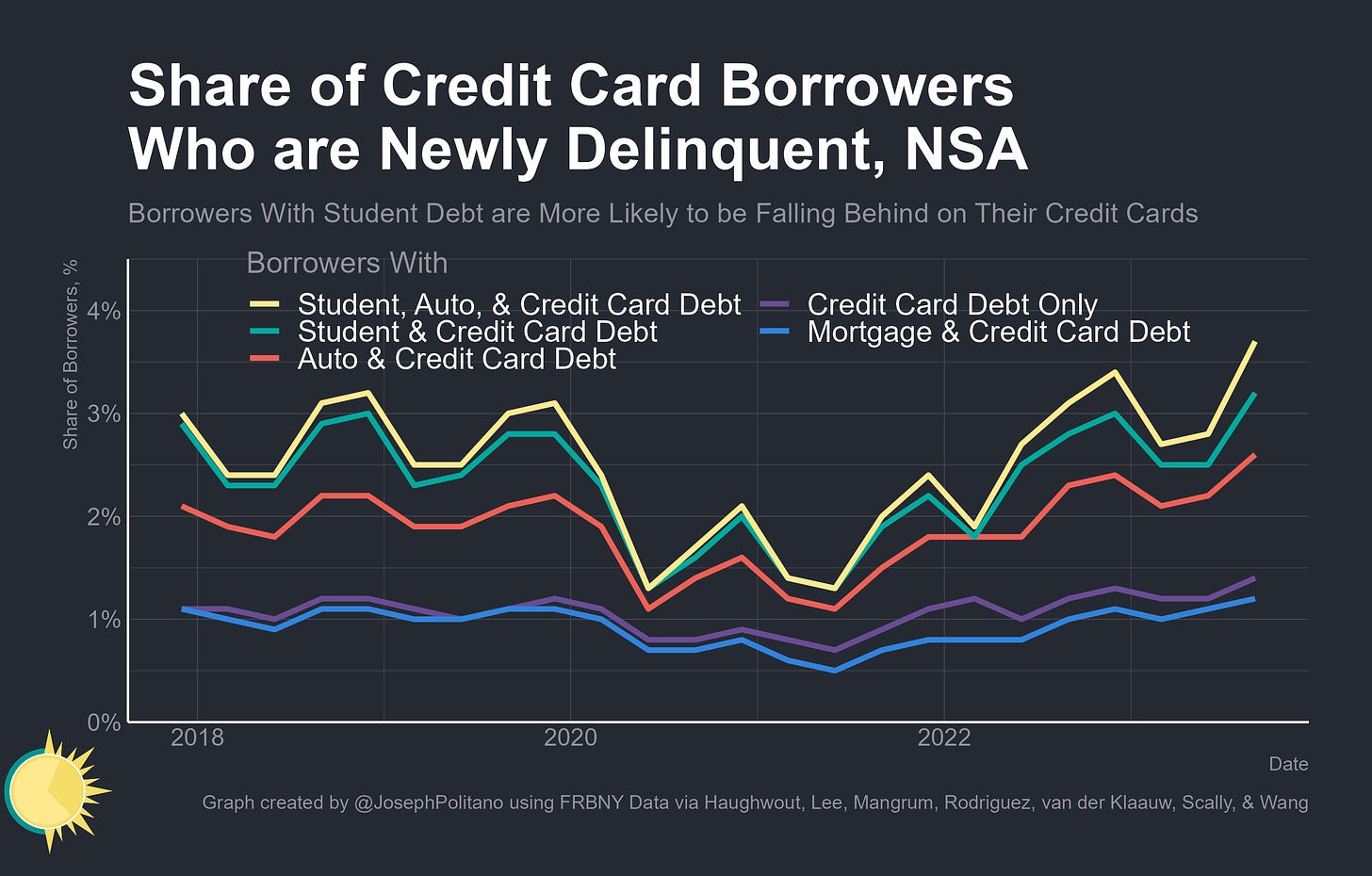

However, just because federal student loan debt can’t yet become delinquent does not mean that student loan borrowers aren’t being financially stressed. Forbearance and stimulus efforts in the early pandemic allowed many borrowers to improve their credit scores and make a dent in other types of consumer debt, but the retraction of fiscal aid, renormalization of consumer spending patterns, and the dwindling of excess savings have all brought overall credit card delinquency rates back up. Student loan borrowers were already more likely than other groups to fall behind on their outstanding credit card payments, and they were transitioning into delinquency at much higher rates than pre-pandemic even before payments resumed. Now the effect is amplified, with a large and growing share of student debtors being unable to make required payments on their credit cards.

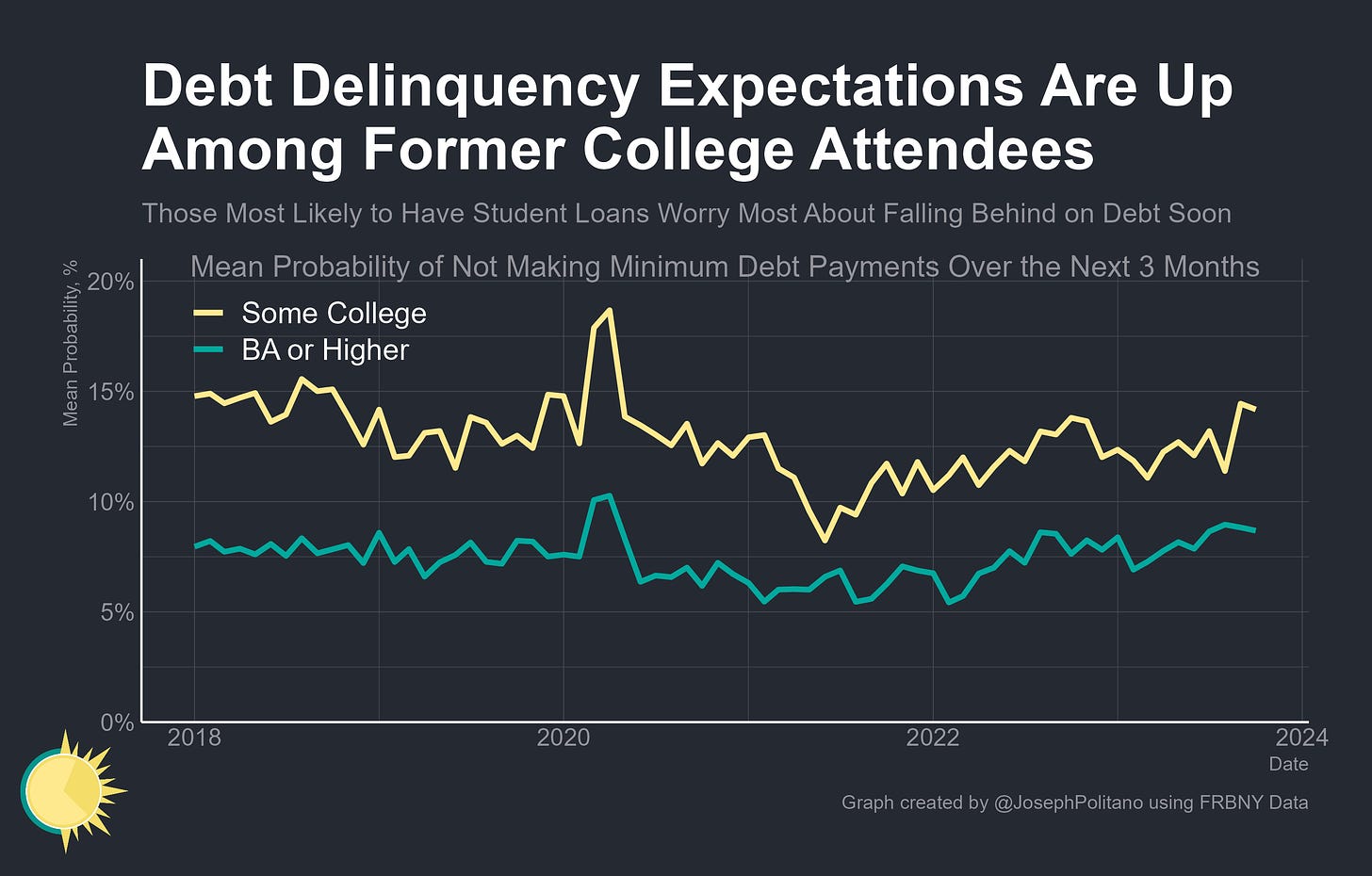

Going forward, those most likely to have student debt are increasingly concerned about their ability to meet their total short-term financial obligations. Former college attendees, whether they graduated or not, estimate their probability of not making the minimum payments on all their debts in the next three months at some of the highest levels in years, with college graduates even placing their odds of falling behind above pre-pandemic levels. In August, borrowers put their chances of specifically missing a student loan payment at 22.6%—with women, those with less than 60k in household income, and those without a college degree putting their odds even worse.

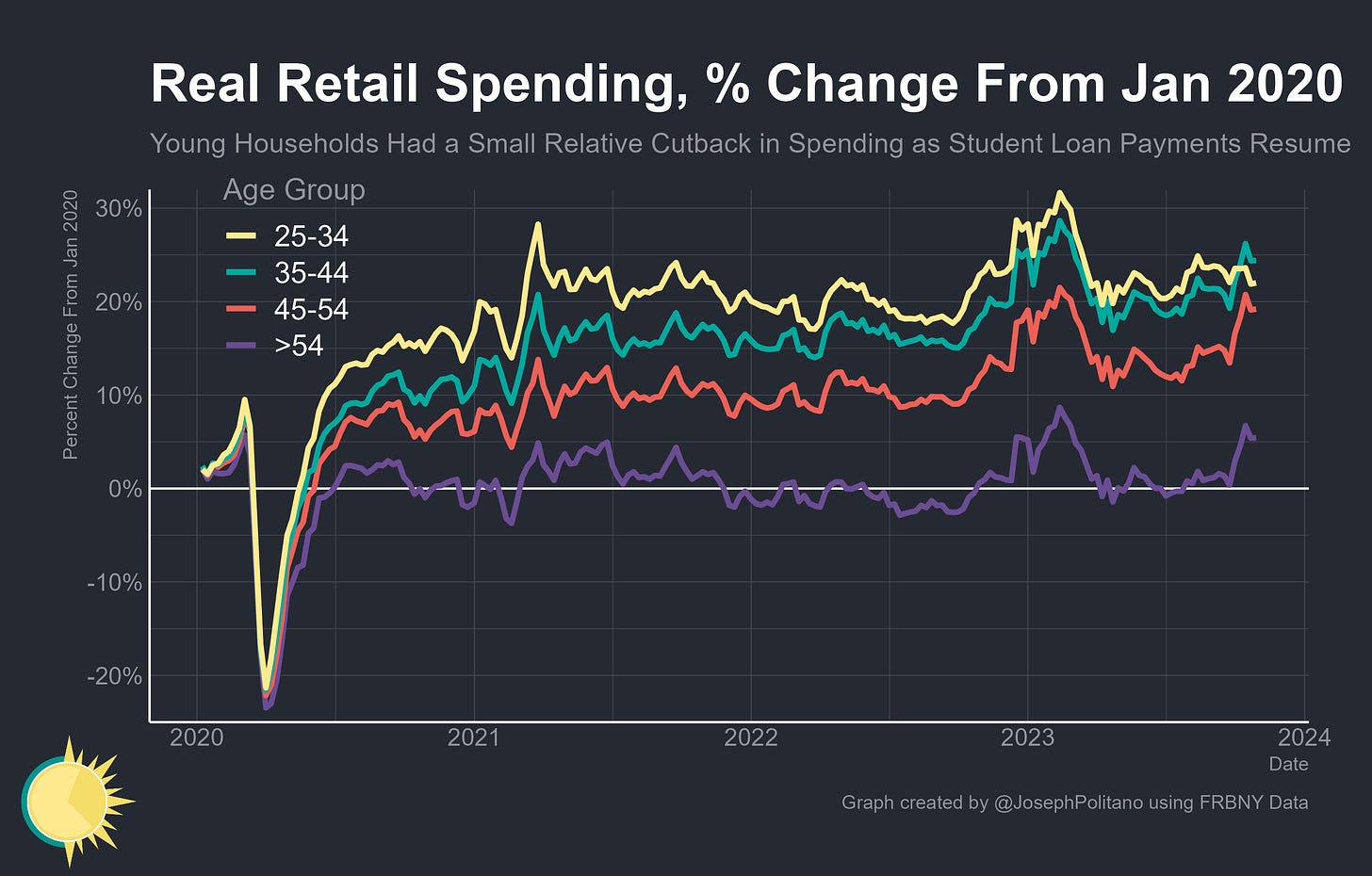

Perhaps most importantly for the broader economy, America’s youngest households have made a substantial cutback in their consumption as student loan payments resume. Since the start of September, real retail spending by those 25-34 years old has fallen by 1.5% at the same time it has risen by between 2.5%-4.2% for all other age groups. However, this recent effect was concentrated among the young with the broader population of all former college attendees regardless of age not seeing a commensurate decrease in spending.

Pulling back, the effect of the end of student loan forbearance on spending has been noticeable but modest. That should not be particularly surprising—when asked, the average borrower expected to spend about $56 less per month as a result of the student loan resumption, much less than their actual average payment size. Plus, even if you unrealistically presume the entire increase in student loan payments resulted in a 1:1 decrease in discretionary spending, the impact would have only reduced October retail sales by about 1%.

The Easing Debt Burden

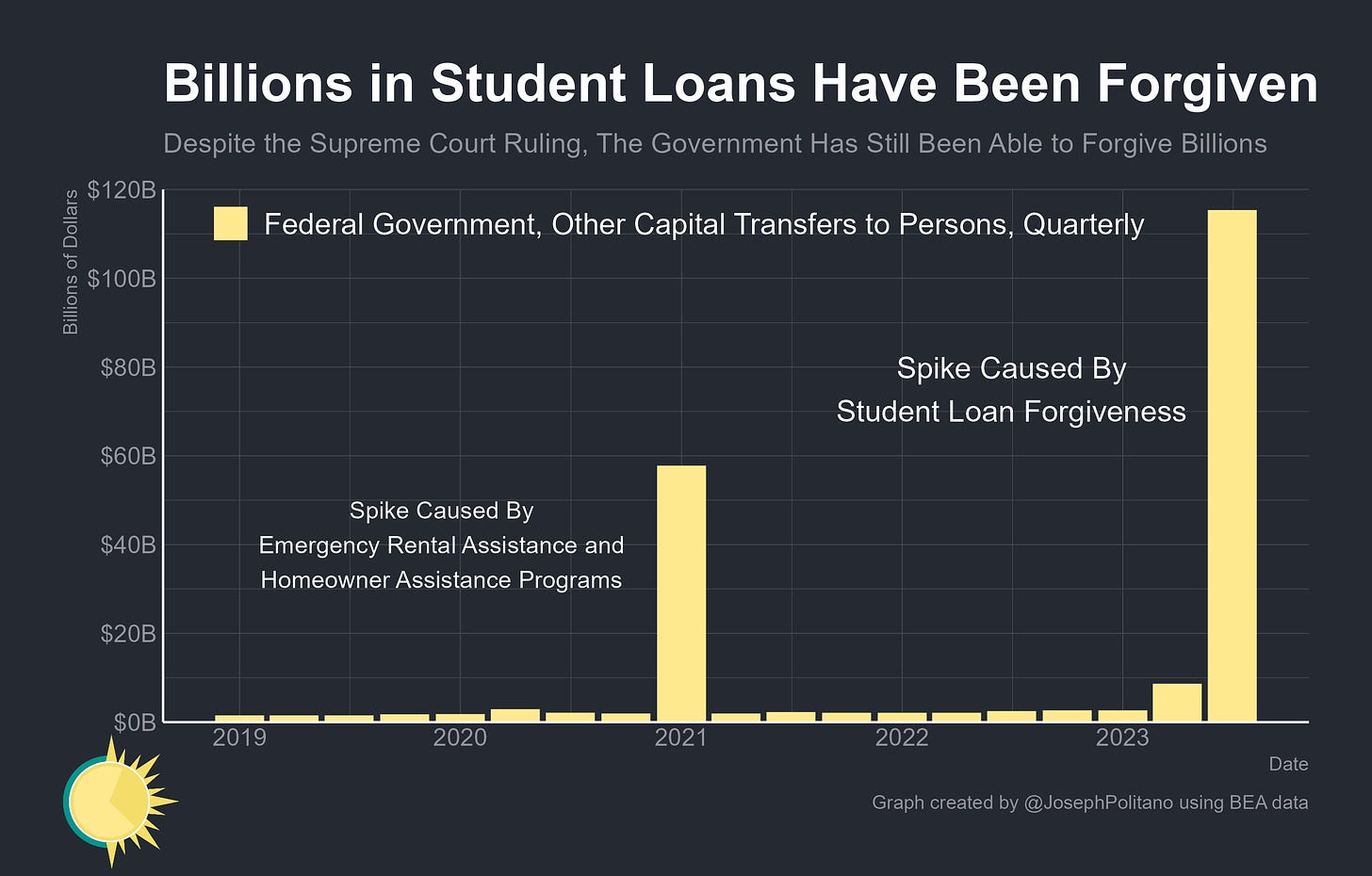

Part of the reason impacts from the student loan payment restart have been so relatively muted is the deliberate policy changes put in place ahead of the end of forbearance. Other capital transfers to persons from the federal government—a niche category tracking movement or disposal of select financial assets—have surged to a record high as nearly $130B in federal student loan debt has been forgiven over the last two quarters. Although the broad student loan forgiveness plan had been struck down by the Supreme Court, billions have still been forgiven via procedure and policy changes for people who completed income-driven repayment plans, public servants, people with disabilities, and those cheated by their schools.

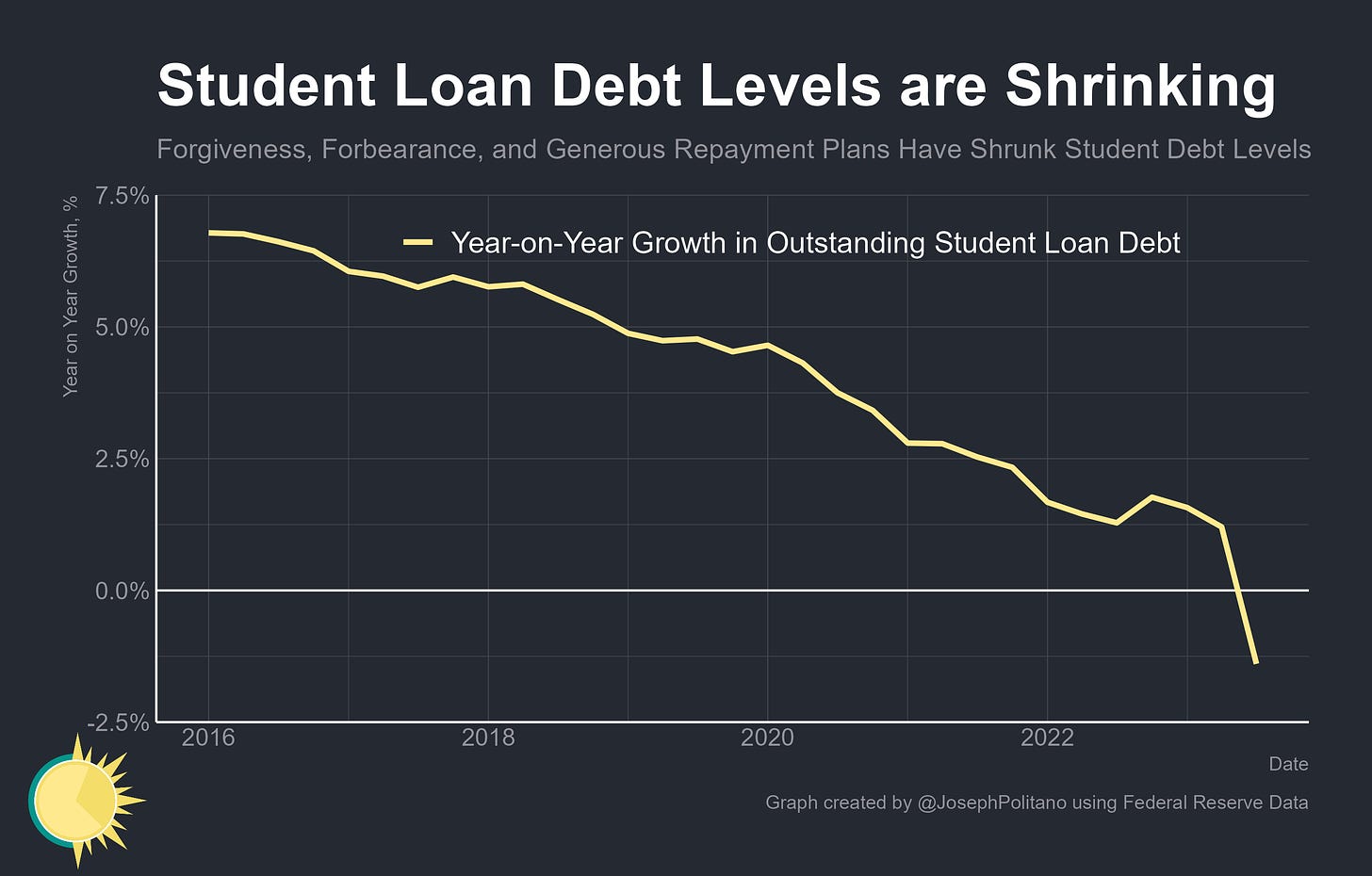

That increase in forgiveness has been so large as to cause the total amount of US student loan debt outstanding to decrease for the first time in decades. Growth in aggregate student loan balances had been slowing for years as the economy improved from the Great Recession, lower interest rates eased repayment costs, demographic factors reduced college admissions levels, and sweeping 2020 policy changes made debt burdens less heavy. In the intervening time since, inflation has chewed away at the real value of the debt, and high wage/employment growth among recent graduates gave them a greater ability to repay. Upcoming policy changes, like updates to the more generous SAVE income-driven repayment plan, look to ease repayment costs further in 2024. That means even as student loan payments restart, their direct costs to households are much smaller than they were four years ago.

Conclusions

Student loans, however, are not all there is to the recent consumer debt story—where tighter monetary policy and higher interest rates over the last two years have steadily fed their way through to rising household interest payments and lower availability of credit. Since the beginning of the Fed’s hiking cycle in 2022, the annual pace of interest payments on nonmortgage consumer debt has increased by $300B, less than $38B of which comes from the recent ending of student loan forbearance. As a share of aggregate personal income, interest costs haven’t been this high in more than 15 years. Meanwhile, the share of households saying it is much harder to obtain credit than it was last year is at the highest levels in more than a decade, and few expect credit conditions to ease anytime soon. In other words, the resumption of student loan payments is only a small part of the broader trend of American households facing rapidly rising costs to service their consumer debt.

Excellent per usual. Can I suggest putting the frequency of the data in the upper right margin of the charts? I'm assuming the FRBNY data is from the CCP which is quarterly, but I wouldn't expect everyone to know that.

Why does the spike then drop in payments suggest people paid off their loans in bulk, rather than suggesting that people have started to pull back on making payments?