The Economic Impact of the Student Loan Restart

Student Loans are the 2nd-largest Source of Household Debt In America, and Payments are Restarting. What does that Mean for the Economy?

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 31,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

An American student who graduated from college in the fall of 2019 has likely never had to make a single payment towards their outstanding student loans. The US government placed all Federal loans into interest-free forbearance at the start of the pandemic, and since then the target date for the resumption of payments has been continually pushed back by successive Presidential administrations. President Biden planned to begin collecting payments again in conjunction with a program to forgive at least $10,000 in student loan debt per borrower—but that student loan forgiveness effort has been stopped by the US Supreme Court, and the debt ceiling agreement signed earlier this year legally now mandates the resumption of student loan payments. So this October, more than three years after the beginning of forbearance, tens of millions of Americans will be once again paying their student loans.

The Biden administration has set up Plan B for implementing student loan forgiveness, essentially taking another shot at the policy under a different legal authority—but there’s no telling if that will succeed, and it will certainly take time to sort out in court. However, separating out the political and legal debates for or against the President’s forgiveness plan, there are the economic realities of the situation: Student loans are a major component of Americans’ household debt, and their restart will have significant effects on households’ balance sheets and spending capabilities. In 2019, Americans spent $70B on their aggregate student loan payments, a number roughly equivalent to the total spent that year on household natural gas, internet service, or durable appliances.

The restart will likely constrain consumers’ balance sheets and spending capabilities further—but in the short term, that pain is not likely to be as extreme as it was pre-pandemic. For one, that is because prior to the official announcement of his student loan forgiveness plan in August 2022, many Americans were still paying significant amounts towards their outstanding student loans despite ongoing forbearance. For two, the administration’s student loan on-ramp plan provides extremely generous concessions for borrowers who have to resume repaying their loans—far from an immediate shock, the policy essentially allows consequence-free nonpayment for the first 12 months after payments officially restart. Thirdly, the myriad of reforms to income-driven repayment plans, programs like Public Service Loan Forgiveness, and other parts of the education finance system means most borrowers could see a substantial fall in their monthly payments even as their debt levels remain the same. It is, however, extremely difficult to forecast precisely how much will be sucked out of the economy as student loan payments restart—mostly because that depends on unpredictable consumer decisions—but the restart will definitely cool down consumer spending even as its impact remains much more muted compared to pre-pandemic.

Understanding the Student Loan Situation

To understand the student loan debt restart, you first have to understand the student loan debtors. 46 million Americans owe some money to the Department of Education for their student loans, and it’s not all young, recent college graduates. Roughly 9.2 million borrowers are over the age of 50, many of whom borrowed to support their children’s or grandchildren’s education, and a large proportion of debt is held by people who did not complete a 4-year degree. The vast majority of borrowers also have comparatively small balances remaining, with 3/4 of debtors having balances less than $40k and 1/2 having balances under $20k.

However, the small contingent of borrowers with large balances holds a disproportionately large share of the outstanding debt—although they make up only 16% of total borrowers, those with balances in excess of $60,000 hold the majority of student loan debt. Their share—and particularly the share of borrowers with extremely large balances north of $100k+—has been increasing over the last few years.

Who has to make student loan payments? Data from the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) helps clear things up. Unsurprisingly, the burden hits most parts of the income distribution except those at the very bottom, and monthly payment levels are strongly correlated with income. That’s both thanks to the aggregate positive returns to education in the labor market and the very literal mechanism by which income-driven repayment plans tie required payment levels to the earnings of households. For example, of the roughly 0.6% of the population with a student loan payment in excess of $1,000 a month, essentially one-half of them lived in households earning $150,000 a year or more. While not radically progressive, the payment restart will most likely take more raw cash from higher-earning American households—with some important caveats we’ll discuss in a bit.

What Forbearance Did

Before the pandemic, student loans regularly had the highest delinquency rates of any major household credit category in the US. That’s partly for purely structural reasons—the lender is the Federal government, the loans cannot be discharged in bankruptcy, and the immediate consequences for nonpayment are much lower (they cannot repossess your degree the way they can your car). Indeed, when asked what bills they’d stop paying first Americans tend to rank student loans near the forefront for precisely these reasons. Yet there was still a major population struggling to keep up with student loans, and delinquency rates hardly improved throughout the economic recovery of the 2010s even as most other credit categories strengthened. It took the start of forbearance to nearly completely eradicate student-loan delinquency rates, bringing them to the lowest levels on record.

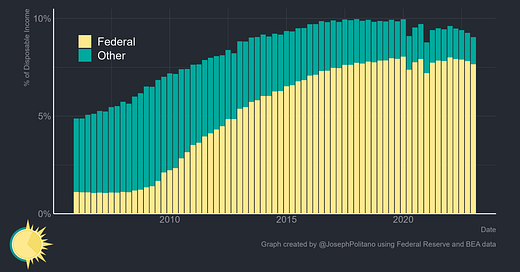

However, it would be a mistake to assume that just because no payments were required no payments were made. Gross payments, including refinancing, took a massive dive in 2020 and 2021, but tens of billions of dollars were still being paid each year even as federal student loans were in forbearance. There was even a rebound in payments during fiscal year 2022—although this likely reflects a surge in the refinancing of federal debt with private lenders. With the vast majority of borrowers’ interest not accruing, almost all payments went towards the principal of loans, leading to the first major shrinkage in student loan debt as a share of disposable income in years.

Who continued to pay? It’s impossible to say precisely—there was a meager subpopulation that voluntarily chose not to put their federal student loans into forbearance and a not-insignificant amount of people refinanced their student loans, but it’s also likely true that most repayments came from people voluntarily taking advantage of the forbearance to chip away at their balances. The SHED survey asks about “required payments on educational debt”—not about Federal loans specifically, and not about voluntary payments—but the number of people claiming to be making required payments on their student loans seems incongruous with the Department of Education data. My guess is that while most middle and working-class Americans took the forbearance as an opportunity to pay less during the pandemic, a subset of higher-income Americans continued to chip away at their debts, hence the massive dropoff in self-reported required payments among middle-income Americans and a smaller drop among higher-income Americans. However, we’ll have to wait for the release of the much-more-comprehensive data in the Survey of Consumer Finances later this year before making any deeper determinations.

Yet we can gain some higher-frequency lower-quality information by looking at inflows from Department of Education programs (most of which represent student loan payments) into the Treasury General Account. That data shows the rising prices of consumer essentials and the announcement of Biden’s student loan forgiveness plan drove Department of Education receipts down to the lowest levels since the post-2008 reforms to the student loan system. Higher interest rates also likely contributed here by dampening the appetite for private-sector refinances—Still, it’s likely that people have further cut back on their voluntary student loan payments since late 2022, which could mean more relative pain as required payments slowly restart over the next year.

Regardless, while payments will likely tax $40-50B from consumers over the next year, I would not expect the previous relationship between debt and payment levels to hold up once payments restart, or for the Department of Education’s receipts to rapidly recover to its pre-pandemic trends even as most payments resume. A large part of that is simply due to the generous on-ramp giving consumers more flexibility in a way that makes it hard to predict their behavior, but it’s also thanks to radical changes to income-driven repayment policies that should cut payments for millions of borrowers.

To illustrate what I mean, imagine Sally—a roughly normal graduate, who just finished a four-year degree at State University and has $27,000 in Federal student loan debt at a 3.9% interest rate. Under the current standard 10-year repayment program, she would owe roughly $272 a month to pay off her loans—a daunting sum for someone just entering the labor market. So, she takes a look at the income-driven repayment plans available:

Before this year, one of the most frequently used options by struggling borrowers was the REPAYE plan, which allowed people to direct only 10% of their income above 150% of the Federal poverty line (which is currently about $22,000 for a single earner) towards payments. Hence, as shown on the chart above, if Sally got a job paying anything less than $22,000 a year she would have zero monthly payments under the REPAYE program, if she earned more than $22,000 a dime of every subsequent dollar would go to student loans, and if she made more than about $55,000 it would be cheaper to just go with the standard 10-year repayment plan. Yet the SAVE plan being rolled out this year—which all borrowers using REPAYE will be automatically enrolled in—is even more generous, only taking 10% of all income above 225% of the Federal poverty line, and further changes planned for next year would bring that number down to 5%. Functionally, if Sally made $75,000 in 2024, her monthly payments under the SAVE plan would be roughly the same as if she made $43,000 under the current REPAYE plans.

In addition, there are a lot of quieter student loan forgiveness programs going on under the hood that have not gotten struck down by the Supreme Court. The SAVE plans, for example, also allow original balances under $12,000 to be automatically forgiven after 10 years of payments (with another year tacked on for every subsequent $1,000). $45B has been forgiven through efficiency reforms and changes to the existing Public Service Loan Forgiveness system, $22B was forgiven for borrowers who were cheated by their schools or saw their institutions closed, and $10B was forgiven for borrowers with disabilities. Again, the on-ramp also means that borrowers who are delinquent will face essentially no penalties for the first year after student loans resume and new procedures automatically enroll most delinquent borrowers onto income-driven repayment plans—all of which should dampen the pain of the payment restart.

Taken holistically, the resumption of student loan payments will certainly be a drag on American consumers over the next year, tamping down both inflation and growth, but the impact will likely be smaller than many expect, even without forgiveness.

The New Era of Student Loans?

However, perhaps the bigger and more consequential change to the student loan market has been on the borrowing, not repaying, side. In aggregate, Americans have been taking out fewer and fewer loans to go to college over the last decade, for a myriad of reasons.

At some level, the student-loan crisis of the 2010s was downstream of the broader employment crisis of that era, and as the labor market has strengthened borrowers have been able to get a greater hold on their finances. That means more ways for prospective students to earn their way through school rather than just borrowing—employment rates for teens are at the highest levels since 2008, for example—and it means stronger state governments with higher willingness to support public universities. That, combined with the raw decline in America’s college-age population levels, and distaste among many for zoom-based education, has led the real net cost of attending college to shrink during the pandemic—the end result of which is that the inflation-adjusted debt of new college graduates has been falling for 9 years and their debt to income ratios are now hovering near the lowest levels since the early 2010s. In some ways, the original 2010s-era student loan reforms were a slapdash method to generate some economic stimulus during a critical downturn, as were the 2020s-era forbearance policies, and the payment restart is a slapdash version of contractionary fiscal policy following a period of high inflation. Hopefully, this marks the start of a transition into a more stable long-term education financing system.

As usual, one of the most informative and data driven article on the topic that I have seen to date. Great work.

Hi Joseph... great piece... one other looming issue for which I'd like to hear your thoughts... For borrowers on an IDR plan, the write-off of the remaining balance will potentially be taxable at that point in the future when they've finished the years of payments.

For PSLF, that write-off is explicitly non-taxable but my understanding is that for all non-PSLF plans, this was not written into the law and a temporary fix was added into one of the Biden COVID laws that only extends for a few more years. After that, absent congressional action, the write-off becomes taxable again.

This, of course, would be essentially unpayable when that was to occur. Do we just assume Congress permanently fixes this or is this more trouble down the road?