The Economics of Global Rearmament

How Allies are Supplying the Ongoing Defense of Ukraine and Managing its Growing Costs

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 34,000 people who read Apricitas weekly

In the year and a half since Russia’s invasion, Ukrainian forces have managed to reclaim large amounts of territory and inflict significant personnel and material losses on their opponents. Russia has responded by doubling down, deploying hundreds of thousands more soldiers into the field, and committing more resources to the conflict in hopes of preventing further territorial losses. That defense has meant the current Ukrainian counteroffensive has, thus far, produced smaller gains using more resources than previous counteroffensives, and rising costs on both sides are becoming a key feature of the conflict.

Indeed, Ukraine’s growing need for support, alongside concerns for domestic security in many European nations, has resulted in rising military budgets across many high-income democracies. Yet money alone cannot conjure up all the equipment and munitions necessary for continental rearmament and Ukrainian support. Most Allied nations have spent the last three decades optimizing large parts of their militaries for conflicts against non-state actors—counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency operations—and were left in shortage of some of the key components necessary for combating an invasion from a state actor like Russia. While many of these countries, especially the United States, can draw on their large stocks of existing weapons in order to support Ukraine, those will need to be replenished if the conflict continues much longer. “It is clear that we are in a race of logistics," NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said earlier this year, “Key capabilities like ammunition, fuel, and spare parts must reach Ukraine before Russia can seize the initiative on the battlefield. Speed will save lives."

The good news is that real production of defense equipment and ammunition is ramping up across both the US and EU in the wake of the invasion, even as output is not yet enough to match the conflict’s demands without further inventory drawdowns. At the same time, Allied nations can now bear the rising bill for direct military support much easier than Russia—especially as the cost to protect households against the energy price shock of the last two years continues to fade. While aggregate output in the Russian economy has largely recovered from the initial impacts of sanctions as renewed access to imports has strengthened Russia’s military-industrial capacity, growth over the last few years has still been weak when compared to the EU and especially the US, whose economies were already much larger. Russia is therefore having to spend greater shares of its limited GDP and real economic resources to match military support from Allied nations; although they have stopped publishing detailed government spending data, aggregate Russian federal expenditures now compose a larger share of GDP than during the height of the pandemic, the deficit is at some of the largest levels since the Great Recession, and labor shortages are becoming more frequent. Yet more broadly, rising interstate conflict presents a massive drag on global civilian economies, and countries struggling to keep pace with growth are going to find it tougher to meet defense spending targets without cuts to domestic investment and household consumption.

Europe’s Rearmament

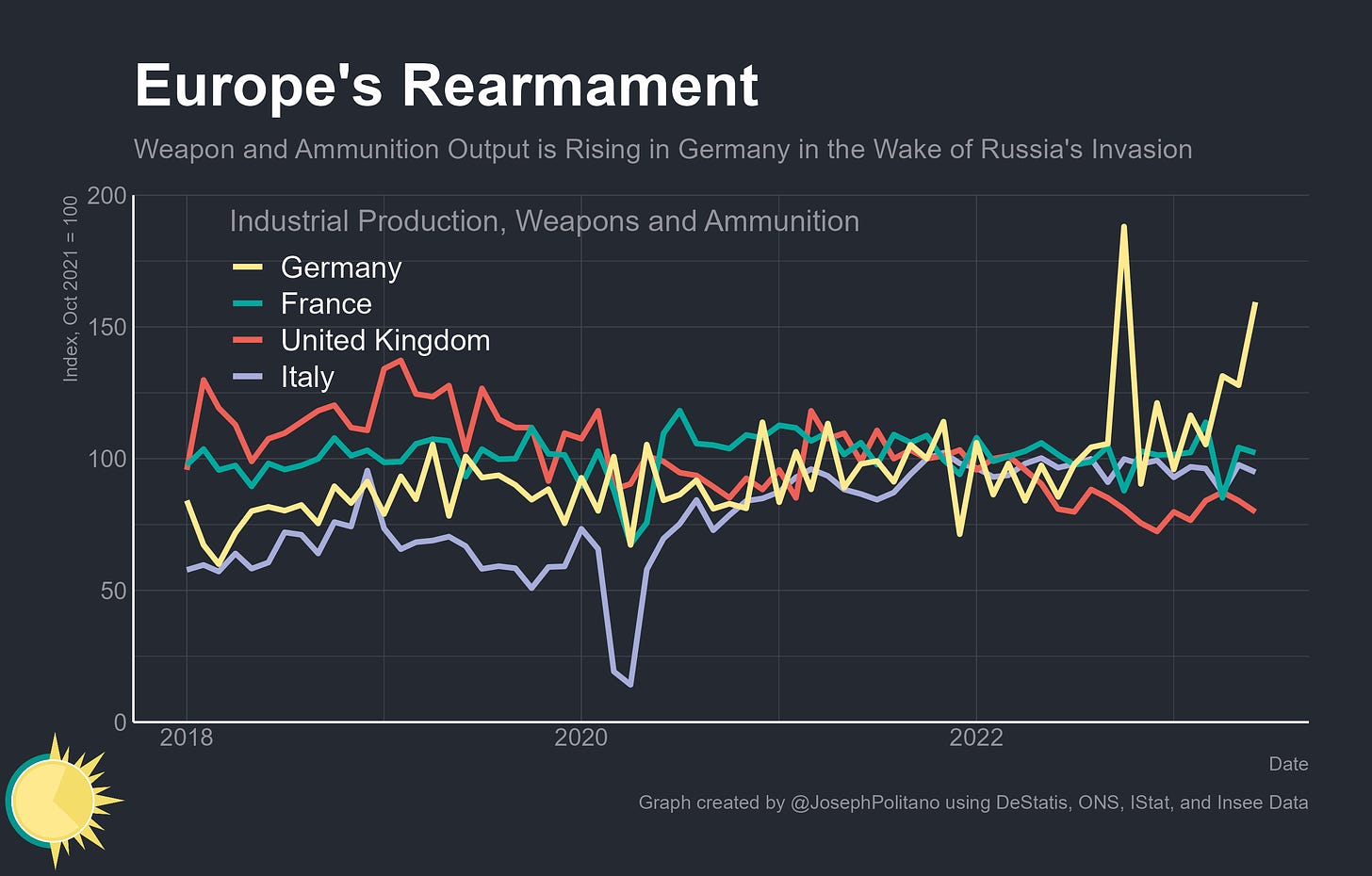

Detailed, publicly available data on international arms production is, understandably, hard to come by—nations generally do not wish to surrender sensitive information on their military-industrial capabilities, especially in times of conflict. Yet there is some amount of valuable insight that can be gleaned from the aggregate figures that many countries do actually publish, and some important detailed data is also available for a few major nations. For example, EU-wide arms production has picked up by roughly 7% since the start of Russia’s invasion and is up by roughly 15% compared to pre-pandemic levels.

However, most of that rise in European weapon and ammo production is coming from Germany—other major EU countries like France and Italy have not seen boosts to their domestic arms production in the wake of the invasion, and the United Kingdom has actually seen output fall since 2022. The important caveat is that it’s hard to glean any separate insight into EU military vehicle manufacturing—although production has been steadily increasing in the decade leading up to the invasion, data from 2022 onwards has not been released.

In Ukraine itself, official government statistics show production of ammo, weapons, and military combat vehicles has surged 30-40% above pre-war levels, more than recovering from the declines seen in the immediate aftermath of the invasion. That is despite headline industrial production falling by roughly 30% due to the effects of the war—though Ukraine’s overall industrial base remains heavily damaged, the redirecting of resources towards military aims has allowed it to raise defense output even as the increase isn't enough to preclude the need for external support. Although data from other Eastern European states is more limited, they are also likely boosting output—as a share of GDP, they have been some of Ukraine’s largest military backers, with countries like Poland seeing arms exports rise significantly and Lithuanian production data showing robust growth.

Pulling back, it’s worth looking at German arms output in detail—both because they remain the largest industrial power on the continent and because they publish some of the most detailed defense production data available. The broad direction for German weapon and ammo production is clearly upward, with trend-adjusted output up roughly 40% from pre-war levels, and more volatile headline data up more than 50%.

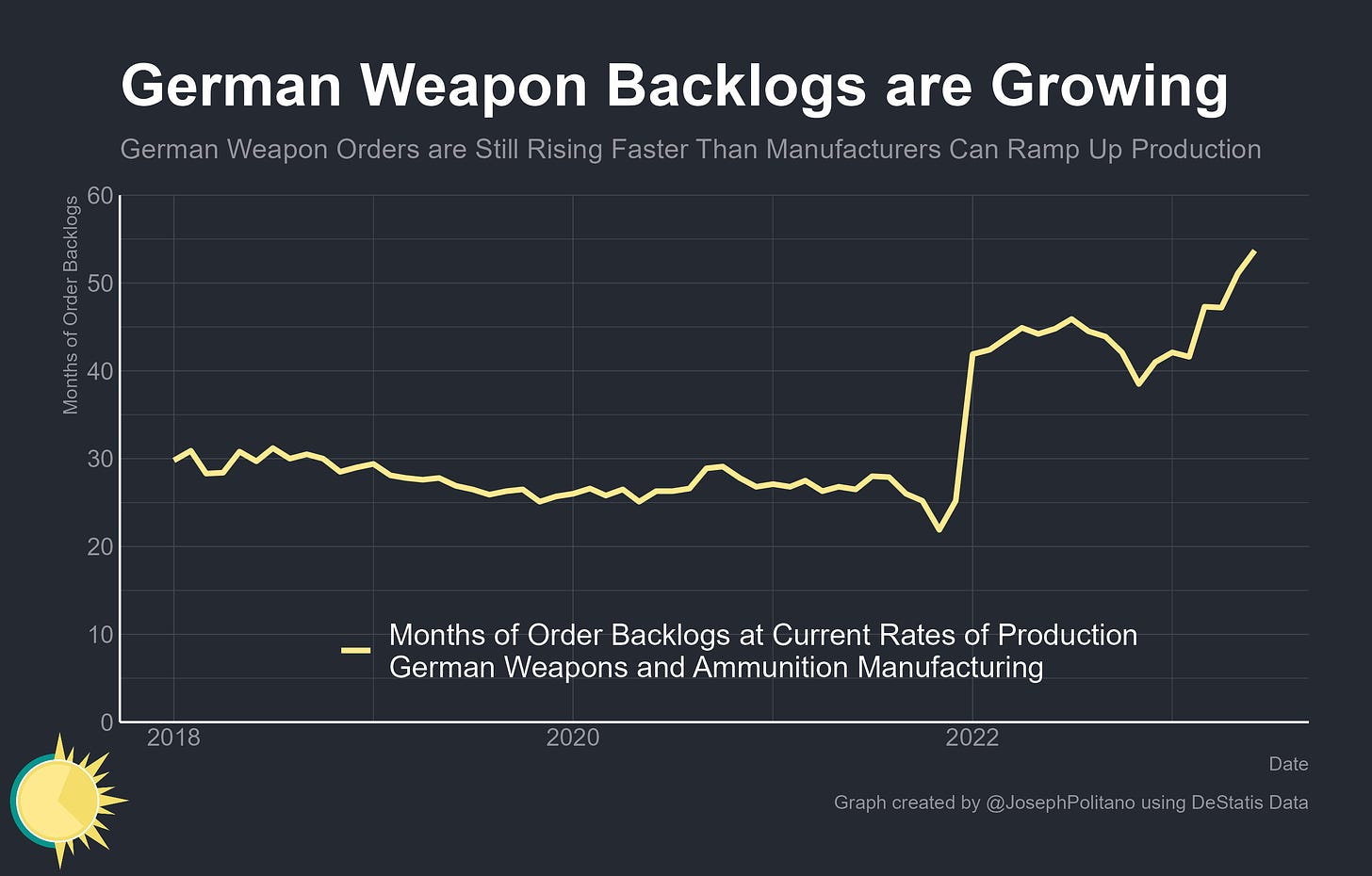

Yet the key dynamic across the German arms industry has been rising order backlogs as the country’s defense industrial base tries to catch up with the demands of the war. At the beginning of 2022, that surge in orders was mostly accounted for by rising foreign demand—Ukraine, its backers, and other Eastern European nations purchasing arms after Russia’s invasion—but in the wake of Germany’s newly implemented defense expansion plans, domestic backlogs are growing too. As of now, total German weapon and ammunition backlogs have increased by more than 150% since the start of the invasion.

The net effect of these shifts is that the growth in German military arms demand is currently outstripping growth in arms production even as both rise precipitously. At current rates of production, it would take arms manufacturers nearly 55 months to clear through the stock of unfilled orders, more than double the roughly 25-month pre-pandemic average. For key subcomponents the backlog is definitely larger—headline data incorporates orders and production of hunting rifles and civilian small-arms ammunition alongside more direct military arms, and the detailed breakdowns available omit military-exclusive output. In other words, European rearmament is happening, but not as fast as necessary and at a significant relative cost.

America’s Defense Spending

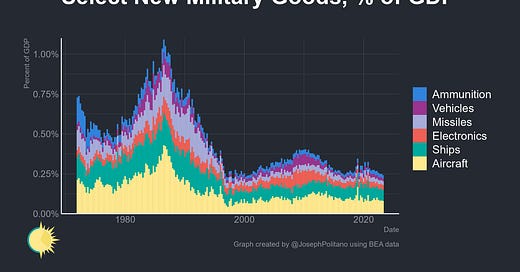

America remains the world’s largest military spender by a wide margin, with a massive economy and outsized defense spending even relative to its overall GDP. That has meant its proportional boost to military investments in the wake of Russia’s invasion has been smaller, especially when compared to many European nations. Aggregate US nominal spending on select new defense equipment has held mostly steady since late 2019, with the dominant share of spending still going toward investments in new ships and aircraft.

Meanwhile, real US spending on ammunition has actually dropped since late 2022 as the fall in consumption caused by the withdrawal from the war in Afghanistan outweighs the increase in spending for the defense of Ukraine. Real spending on new missiles has held roughly steady, though at much higher levels than pre-pandemic.

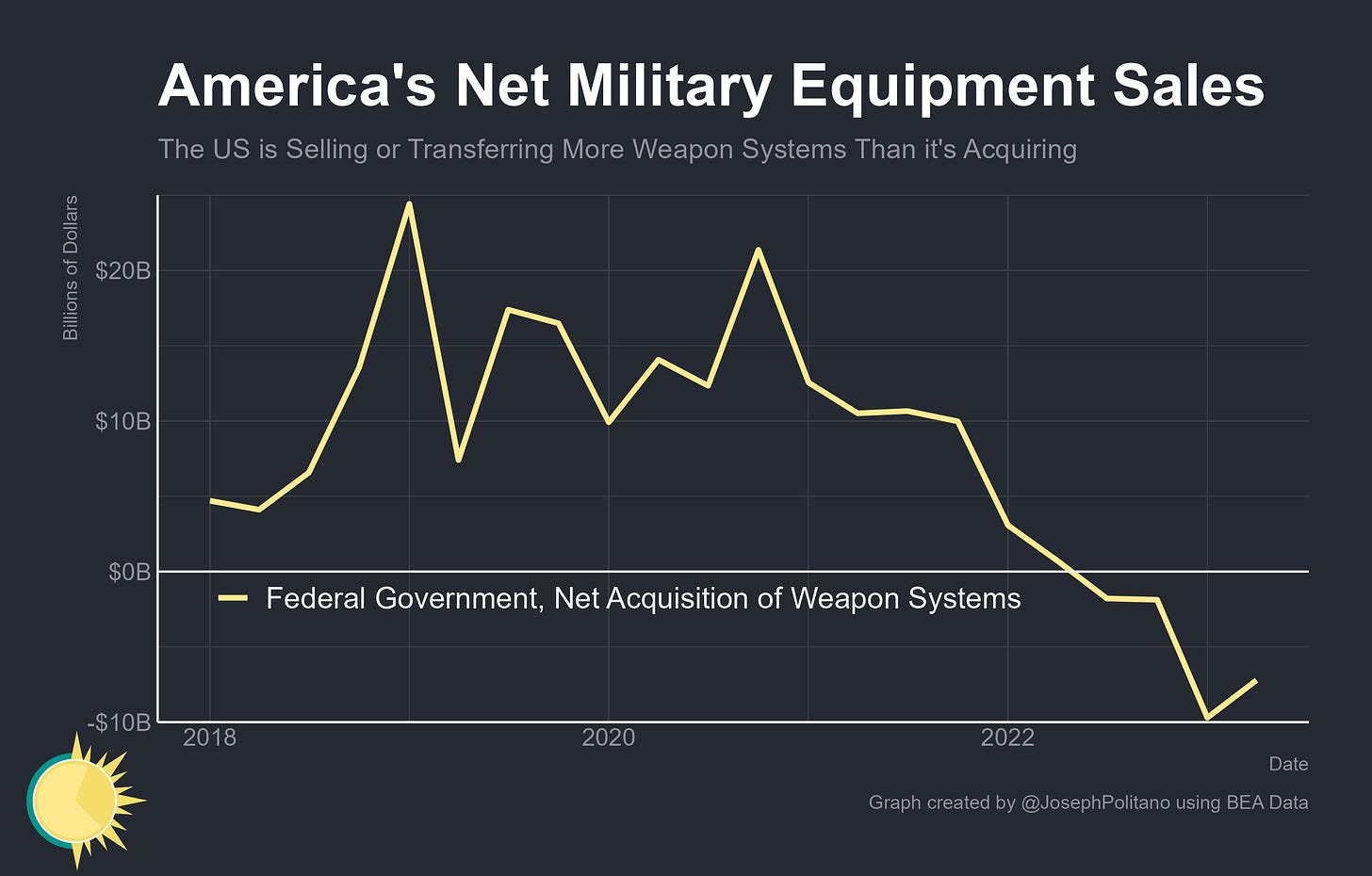

Yet despite the relatively level aggregate spending on defense goods, America has sent far and away the most military equipment to Ukraine during the conflict—nearly €43B so far, more than 5.5 times the military aid from Germany, the second-largest individual contributor. The end result is that the net acquisition of weapon equipment by the US government turned negative by mid-2022 and reached the lowest level in 20 years at the start of 2023—in other words, transfers abroad and the depreciation of existing equipment outweigh the acquisition of new equipment as America sends existing weapon stocks to support Ukraine. There has also been a sharp uptick in US defense sales to other sectors—how transfers of ammunition and other intermediate goods to Ukraine are classified—alongside real purchases of material transportation services to facilitate hardware transfers.

American military manufacturers’ order backlogs are also up, though likely to a smaller degree than their European counterparts. Nominal unfilled orders for defense capital goods—which includes ammo, tanks, planes, ships, missiles, electronics, and so on—held roughly steady in the immediate aftermath of the invasion but have since picked up about 5% in 2023.

Shipments from US defense manufacturers have, in turn, also increased—up roughly 12% in nominal terms since the start of Russia’s invasion to some of the highest levels since the early 1990s. Though it’s not possible to completely break down the orders into all their subcategories, by excluding aircraft and some other defense equipment it’s clear that the jump in US shipments is mostly driven by small arms and ordnance, missiles, spacecraft, ships, and boats.

However, it’s critical to keep in mind that the relative cost of new defense equipment is still near the lowest levels in modern US history—as a share of GDP, defense acquisitions have fallen since the start of COVID, which in turn represented a steep decline from a decade prior.

Likewise, total US nominal defense spending as a share of GDP is also close to late-1990s peace-dividend-era lows despite the growing level of support for Ukraine. Indeed, Allied nations’ greatest advantage is their growth and economic heft, which gives them the capacity to keep supporting Ukraine alongside managing domestic defense objectives in a way that is much more costly for Russia to match. America’s real economic output has grown by 6% since the start of COVID-19, an amount equivalent to $1.5T in today’s money. That economic growth alone is equivalent to nearly 80% of the IMF’s forecast for the total nominal size of the Russian economy in 2023, or about 30% of the size of the Russian economy when adjusting for Purchasing Power Parity (though for a large share of military equipment, the nominal figures are arguably most relevant—it is hard to get PPP discounts on fighter jets). Plus, the US withdrew from a costly war in Afghanistan during this time period, freeing up billions in military resources that would otherwise be directed there. America’s defense aid to Ukraine has been far and away the largest of any country, but as a share of annual GDP it is only 0.2%—the 15th-highest among backers, just behind Czechia. EU-wide economic growth has been much more muted—3.2% since the start of COVID, representing roughly half a trillion in today’s Euros—as the bloc is hit harder by the direct impacts of rising food and energy prices, and the costs are significantly harder to bear. Yet even this amount of economic growth is fairly large compared to the relative size of the Russian economy.

The Cost of Russia’s War

That discrepancy in economic growth and capacity means that the Russian military is likely consuming the largest share of GDP since the fall of the USSR at the same time the US military is consuming a modern-low share of GDP. Russia also already had roughly 2% of its labor force engaged in the armed forces before the invasion—a share more than double America’s and five times the UK’s—and that number has certainly increased as more personnel are brought into the conflict and Russia deals with significant net emigration.

Plus, Russia’s federal budget deficit is also growing as the country borrows to pay for its invasion—the headline deficit approached 5% of GDP over the last year and exceeded 11% of GDP when excluding oil and gas revenues. That is not immediately catastrophic, as Russia has only a small amount of preexisting government debt and financing was never the main constraint on Russia’s wartime capabilities, but it helps put the growing monetary costs of the war in perspective.

Yet very rarely is the price to build a weapon greater than the costs it inflicts when used. The primary economic burden caused by the war in Ukraine is borne by Ukrainians, and although those costs aren’t accelerating, they remain massive. The war is still far and away the dominant obstacle to Ukrainian economic growth, with a large majority of businesses having their operations directly impeded by the conflict. Ukrainian mining and manufacturing firms were less likely to cite the conflict as an obstacle to production than at the initial onset of the invasion, thanks in large part to improved air-defense systems, reclaimed territory, and efforts to rebuild targeting civilian infrastructure. However, agricultural firms are more affected by the war than ever before as Russia looked to further constrain Ukrainian exports.

Indeed, Russia's recent decision to back out of the Black Sea Grain Initiative, which allowed large amounts of Ukrainian agricultural goods to leave the country’s ports, has helped send the total dollar value of Ukrainian goods exports to the lowest levels since the beginning of the war. That has obvious direct impacts on the Ukrainian economy, but also important spillover effects for global food prices that remain elevated in the wake of the invasion.

The primary costs of the war for the defenders will be recovering from those economic impacts and attempting to rebuild Ukraine’s civilian economy. The bilateral commitments of €71B in financial aid and €13B in humanitarian aid to Ukraine are roughly equivalent to the €80B in military aid given thus far, and American grants to foreign governments have risen significantly from prewar levels. Yet recent intergovernmental estimates have placed the full cost of reconstruction at a staggering $411B over the next decade, and that is before accounting for the global costs of elevated food and energy prices or, most importantly, the loss of life in the conflict.

The idealized goal of defense spending as a public good is to mitigate these costs—and to put adversaries in a situation where the price of initiating war is greater than the price of maintaining peace. Larger NATO military capabilities in Eastern Europe, or a more forceful response to the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea, may have been enough to deter the 2022 invasion, and if successful those investments would have paid for themselves many, many times over. Instead, by underinvesting ten years ago they have ended up paying a much higher price today. Yet the US, EU, and other allied democracies still have the economic capability to make those investments now—the question is primarily whether they have the political will and coordination to do so.

Outstanding piece. Would love to see follow up analysis on this topic

This such a great run down of the economics of the war. Thank you.