The EU Joins the EV Trade War

The EU is Imposing Historically Large Tariffs on Chinese EVs in an Effort to Protect Its Car Industry. Will it Work?

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 46,000 people who read Apricitas!

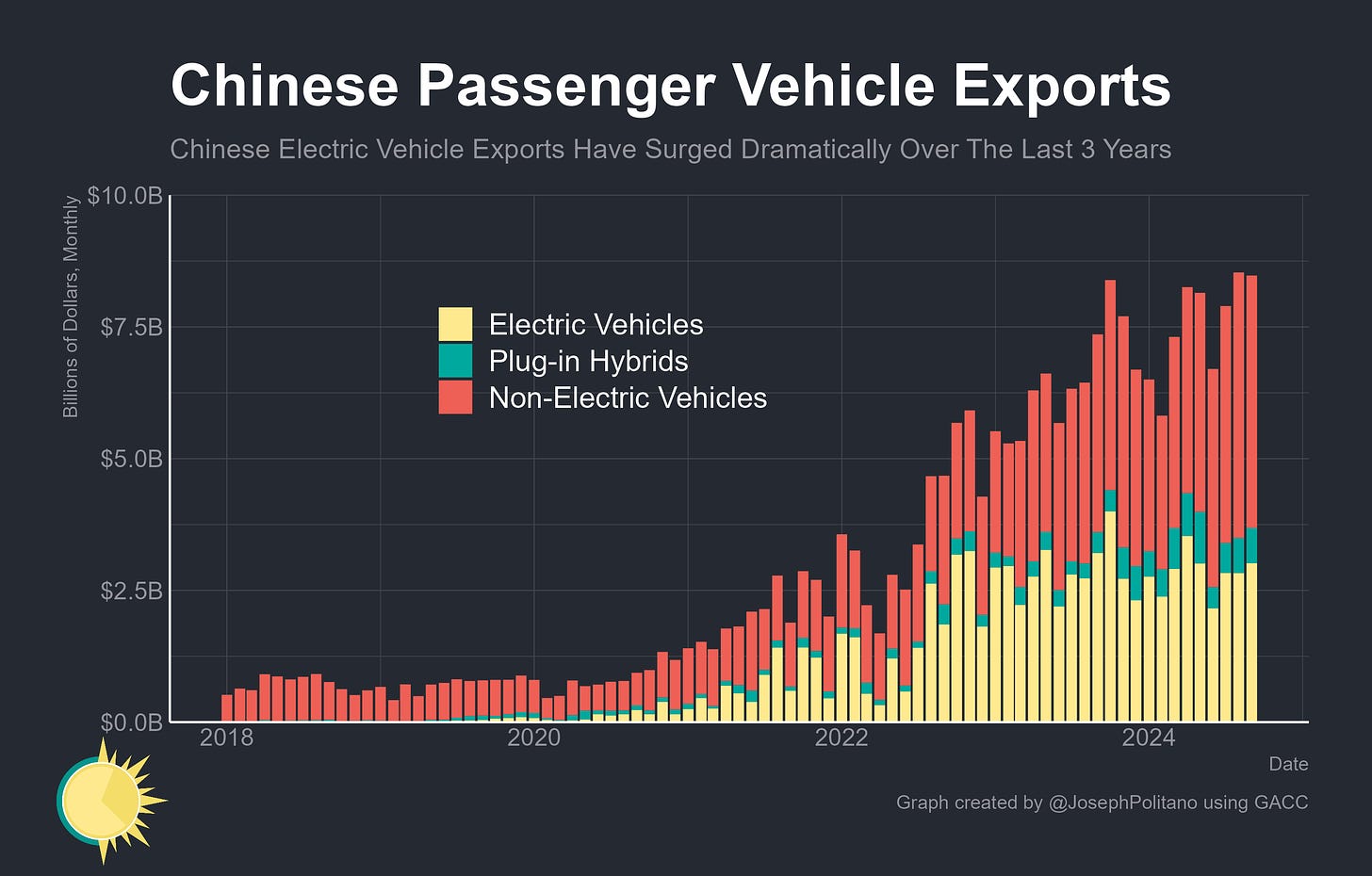

China’s electric vehicle (EV) manufacturing industry is the world’s largest, fastest-growing, and most technologically advanced—and the nation’s rapid increase in EV exports continues to spark protectionist backlash. Earlier this month, the EU officially joined the increasingly wide-ranging trade war against China’s EV industry when the European Commission voted to approve high tariffs on the vehicles after a year-long anti-subsidy investigation. The tariffs, which have been in place provisionally since July, are not as large as the 100% duties that America placed on Chinese EVs earlier this year, but still reach as much as 38% on certain manufacturers and could persist for as long as half a decade.

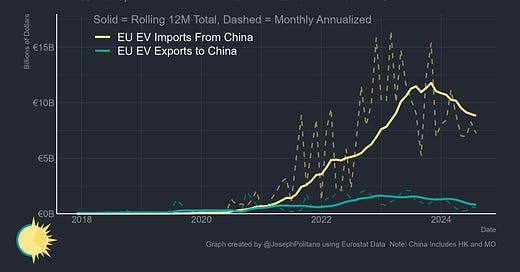

Yet when the US announced its tariffs on Chinese EVs, that was not a major change to the status quo—long-standing DC policy has been to functionally ban all Chinese-made EVs, the increased tariffs just reinforced that already-existing ban. Not so in the EU, where China has rapidly become the bloc’s largest source of imported EVs and has been steadily outcompeting many domestic automakers. In the twelve months before the start of the antisubsidy investigation, the EU imported more than €11.3B worth of Chinese EVs, while China bought only a paltry €1.36B worth of European EVs.

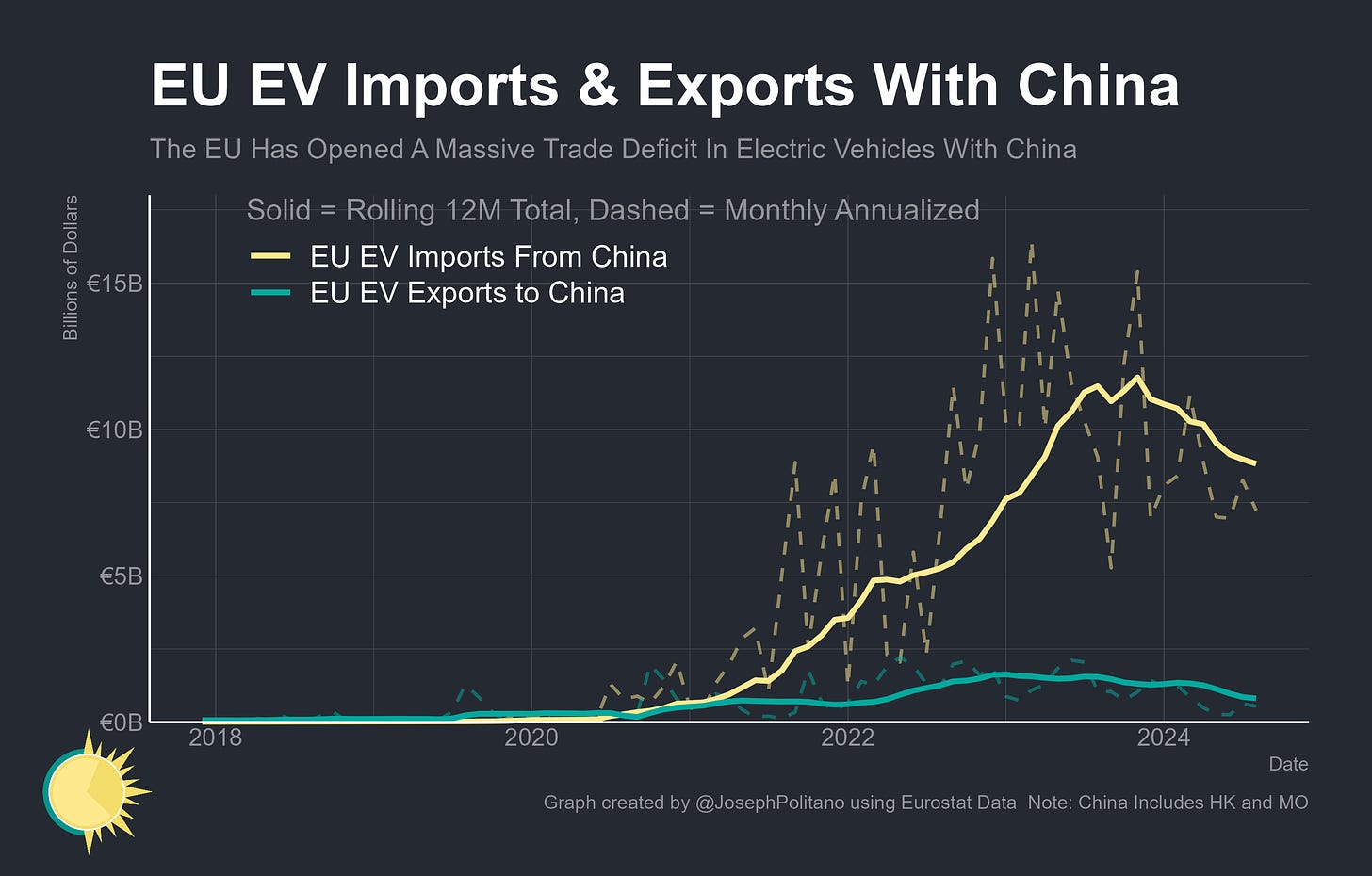

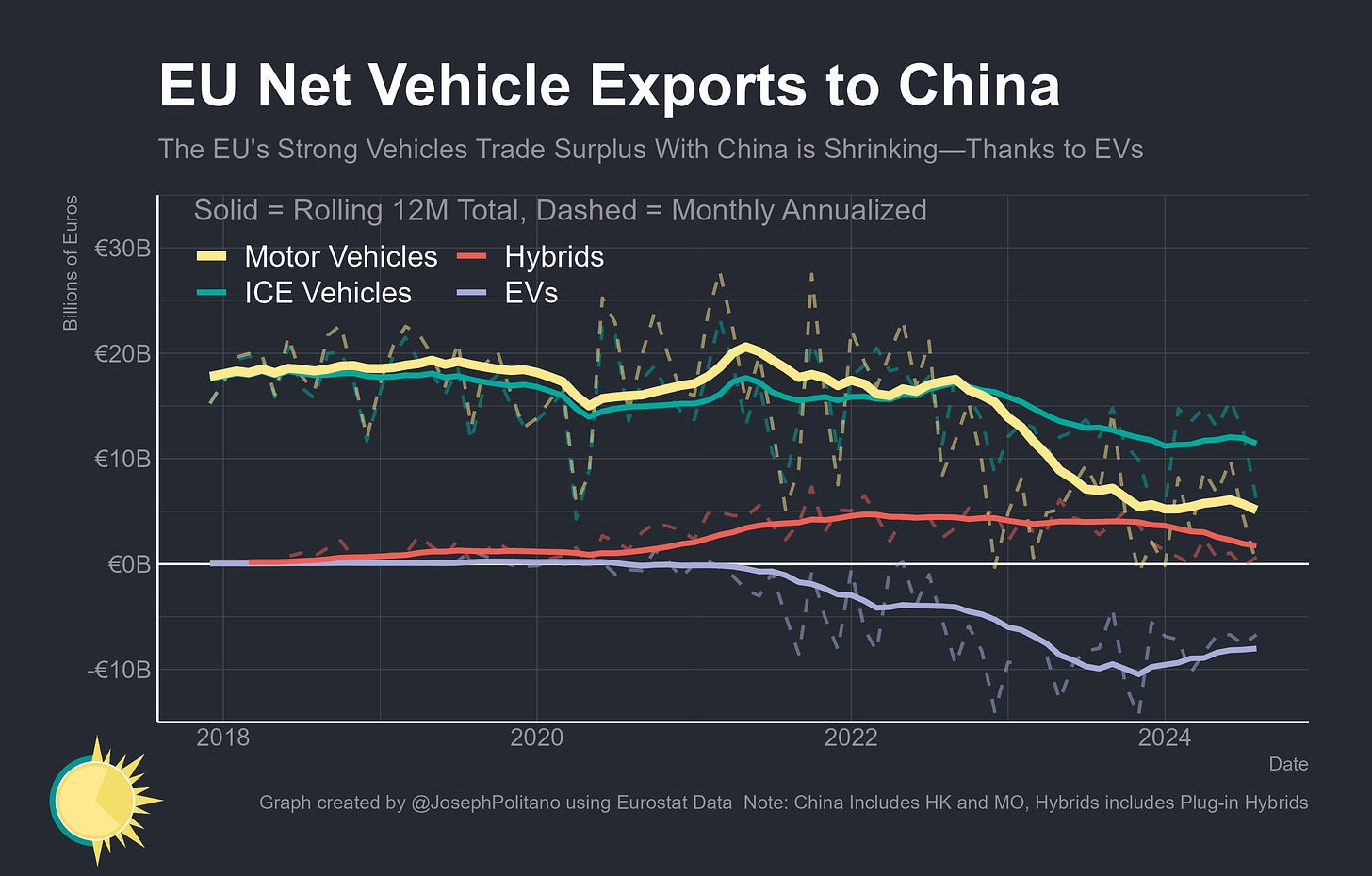

Indeed, the boom in Chinese EV production has rapidly shaved down the EU’s long-standing vehicle trade surplus—the bloc’s total net automobile exports to China stood at €16.9B in 2022, but they have fallen to only €5.1B over the last twelve months. That reduction has come both via a massive increase in net EV imports from China plus a significant decrease in net internal-combustion engine (ICE) exports to China. Thus, the tariffs hope to restore the EU’s vehicle trade surplus by cutting into the growth of Chinese EV imports, which have already decreased since the antisubsidy investigation began and preliminary tariffs were implemented.

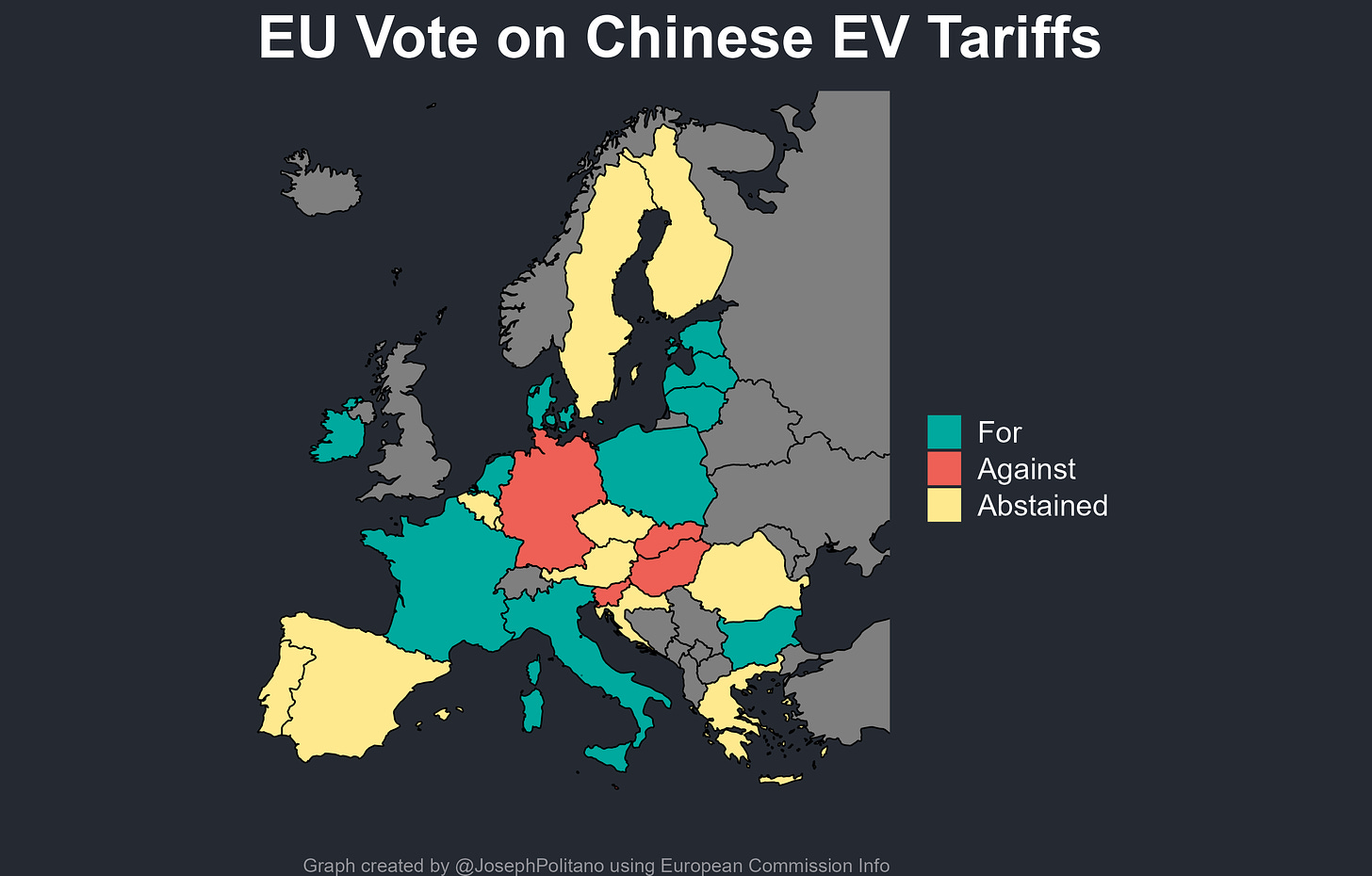

Yet the EU was far from unified on the move to more permanent tariffs, with the bloc’s weak economic standing and the threat of Chinese retaliation making the possibly-substantial economic costs tough to swallow. Germany—the continent’s largest economy, one of the world’s leading car manufacturers, and a country with deep industrial ties to China—abstained on the provisional tariffs but voted no on the final proposal after intervention from Chancellor Olaf Scholz. For its part, Spain voted yes on the provisional tariffs but abstained on the final vote after a high-profile meeting between Spanish PM Pedro Sánchez and Chinese President Xi Jinping. Major players like France, Italy, Poland, and the Netherlands voted for the tariffs, which was more than enough to enact the proposal when coupled with the smattering of smaller supporters—yet key carmaking nations like Slovenia, Slovakia, and Hungary still joined Germany in formal opposition.

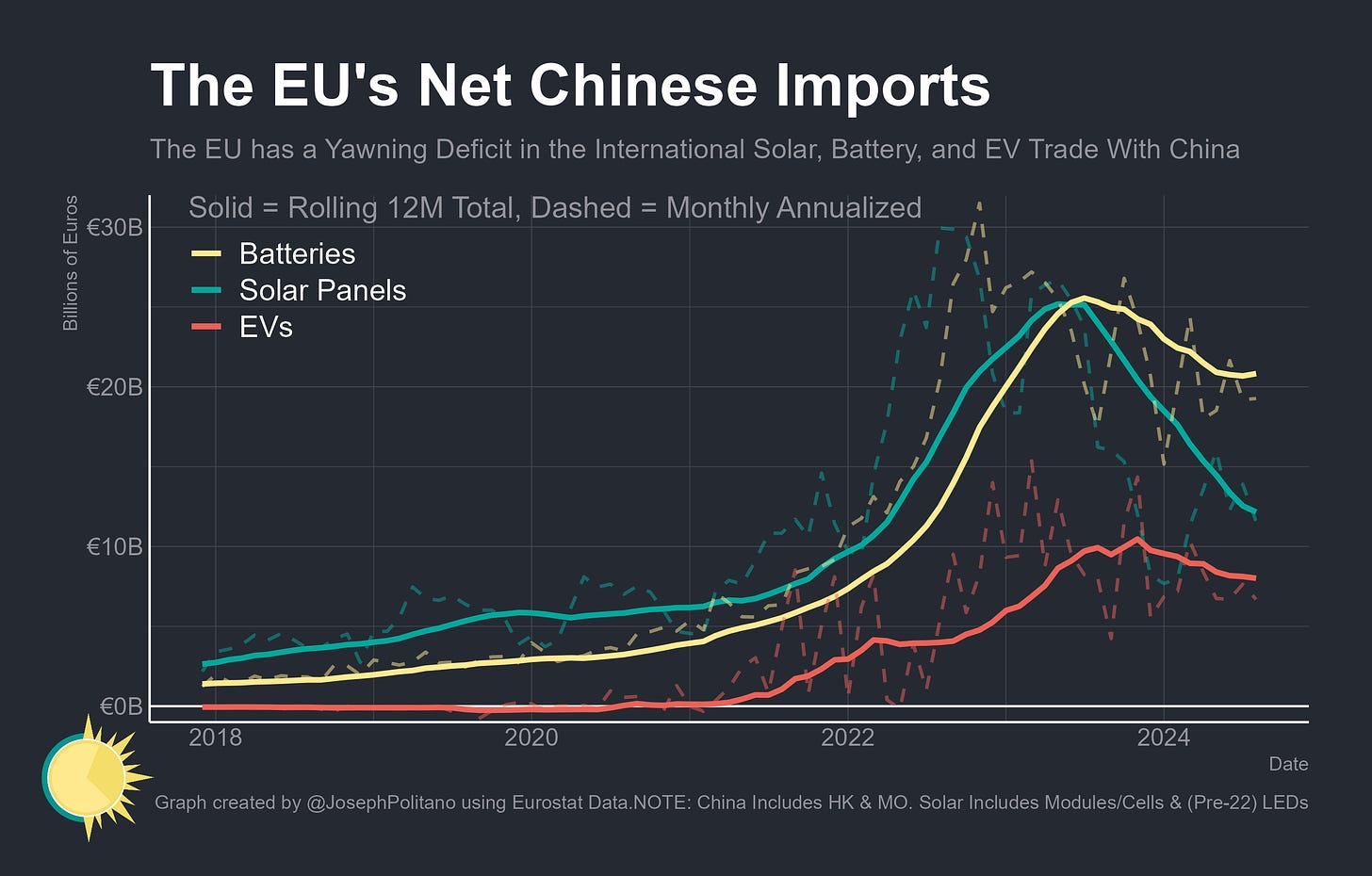

Perhaps even more importantly, the tariffs will not address the EU’s large dependencies on China for the battery supply chains essential for EV manufacturing nor the solar supply chains that power growing electrification. In fact, the bloc’s net imports of Chinese batteries and solar panels each dwarf imports of EVs—and for both categories the share of total EU imports that come from China is higher as well. Batteries in particular are an extremely key ingredient in EV production, as they make up a large part of the differences in production costs and technological capabilities among modern EVs, and the European battery industry has been extremely slow to get off the ground.

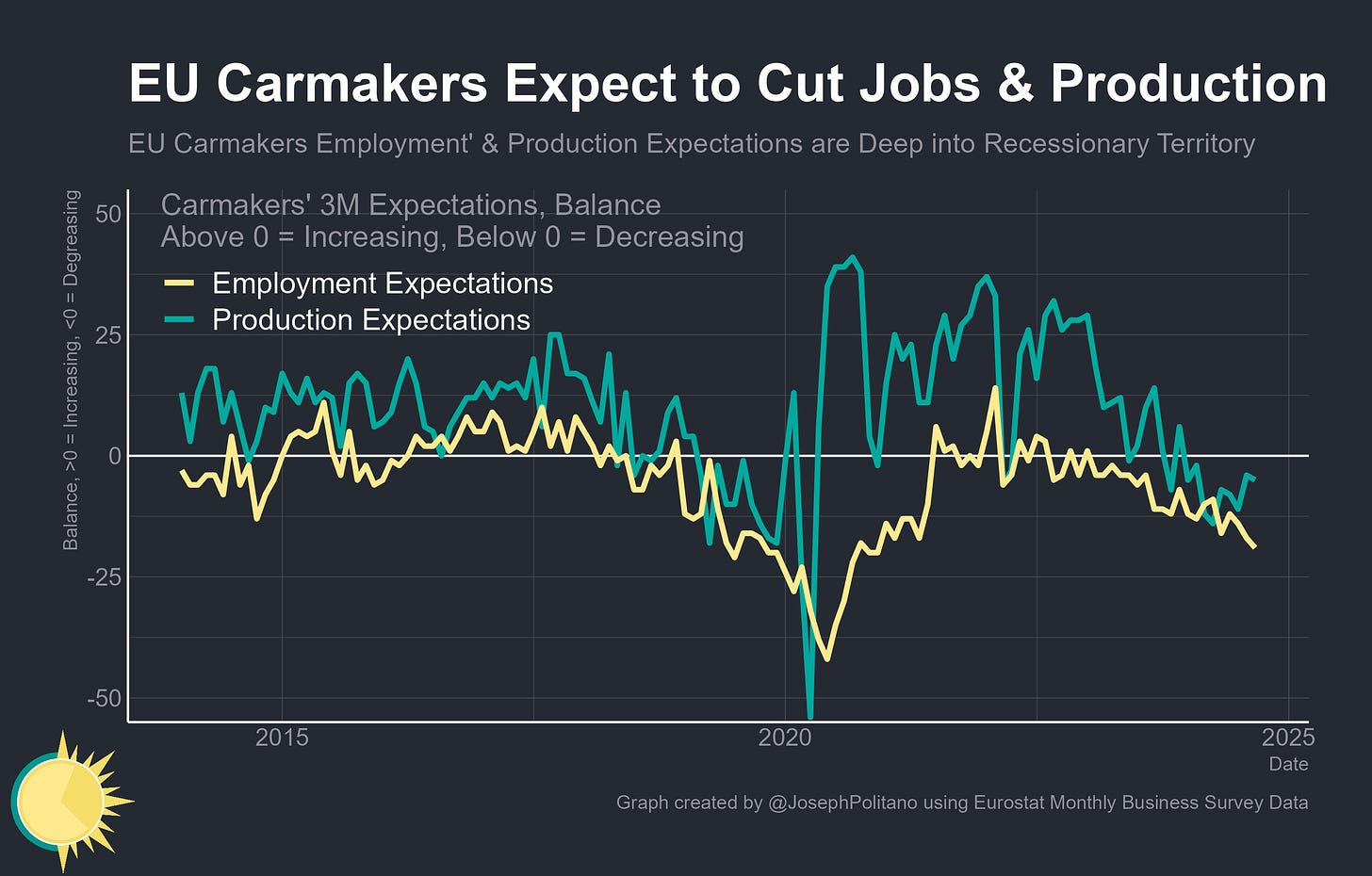

Moreover, European carmakers remain in an extremely weak economic position as these tariffs are implemented—their short-term forecasts are deeply in recessionary territory, with the majority of companies expecting to significantly cut their employment and production levels in the near term. The backlog that sustained automakers for years has largely dried up, domestic vehicle demand remains weak, and EU firms are slipping behind technologically, all of which have culminated to form a massive negative shock to the bloc’s car industry.

That could get worse if some negotiated resolution to this trade war cannot be reached, as China has many possible avenues of long-term retaliation. The country still imports more vehicles from the EU than vice-versa and could cut counter-tariff major European carmakers, hence why leaders at Citroën, Mercedez-Benz, Volkswagen, and BMW came out against the tariffs to varying degrees. China could also leverage other key trade targets in industry or agriculture to hit an already-weak EU economy—threats against EU pork producers were instrumental to preventing countries like Spain from supporting tariffs, and China’s first act of retaliation was against EU cognac. Plus, there is a reasonable risk that current tariffs just fail to induce meaningful reshoring—importing significant numbers of Chinese EVs may remain economical even with these new taxes applied, putting most of the incidence of new tariffs on EU consumers without inducing more domestic investment. Yet no matter what the end results may be, the tariffs represent another chapter in the growing backlash against China’s manufacturing export boom and the steady fraying of manufacturing supply chains along geopolitical lines.

The Backlash to China’s Car Export Boom

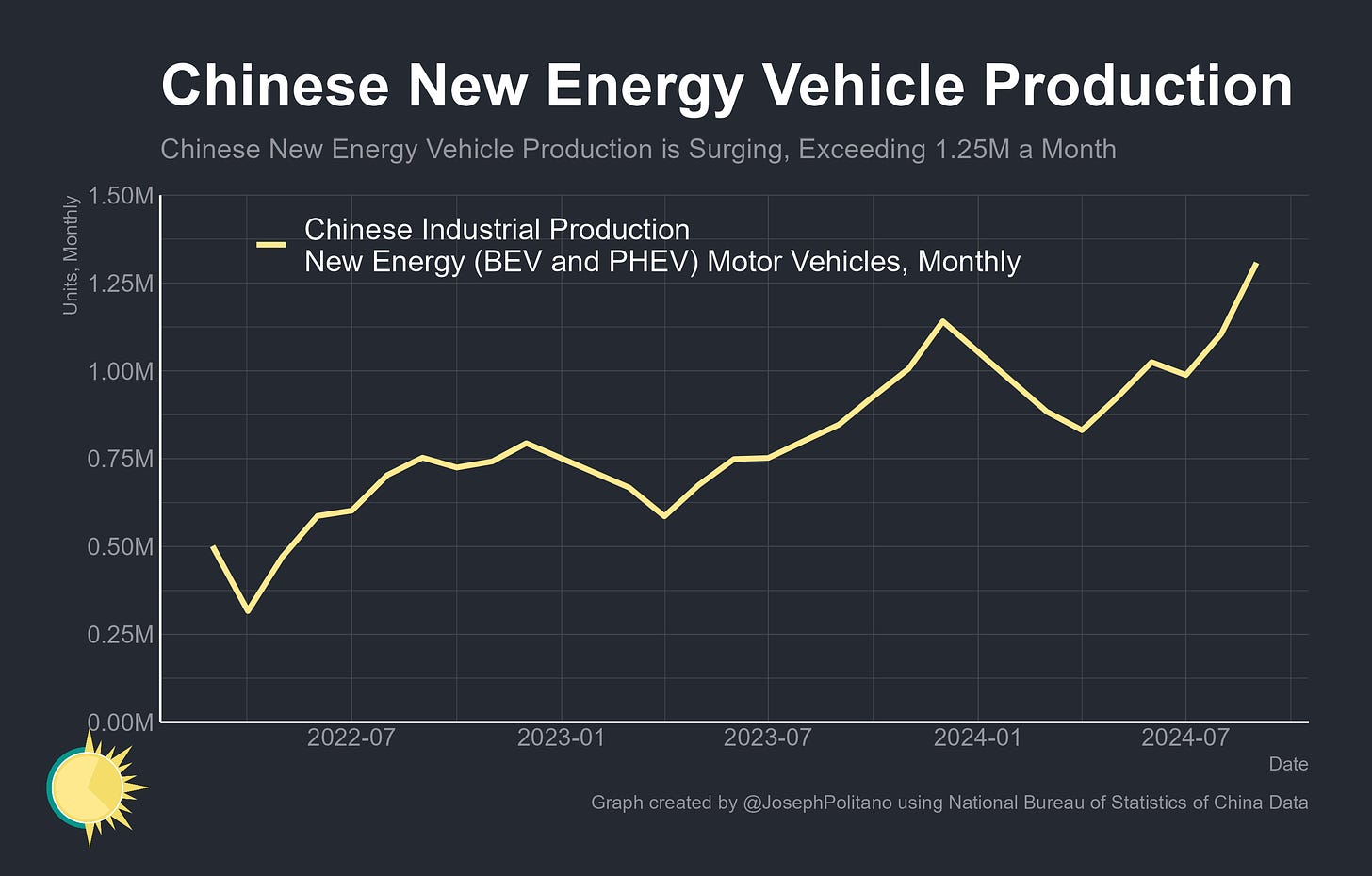

China’s EV industry is currently booming—production of “New Energy Vehicles” (NEVs)—which cover fully battery-electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids—set a new record high in August and is up more than 48% from last year. NEVs now represent nearly half of all vehicle production in China, the raw volume of Chinese NEV output is on pace to exceed the total volume of all vehicles manufactured within the EU or US this year, and Chinese brands like BYD, SAIC, & Geely are rapidly becoming among the largest automakers on the planet. This success has come from innovations on the product and production front—Chinese EVs are now more technologically advanced than many of their overseas competitors, tend to be produced for lower prices, and have benefitted from rapid increases in manufacturing productivity.

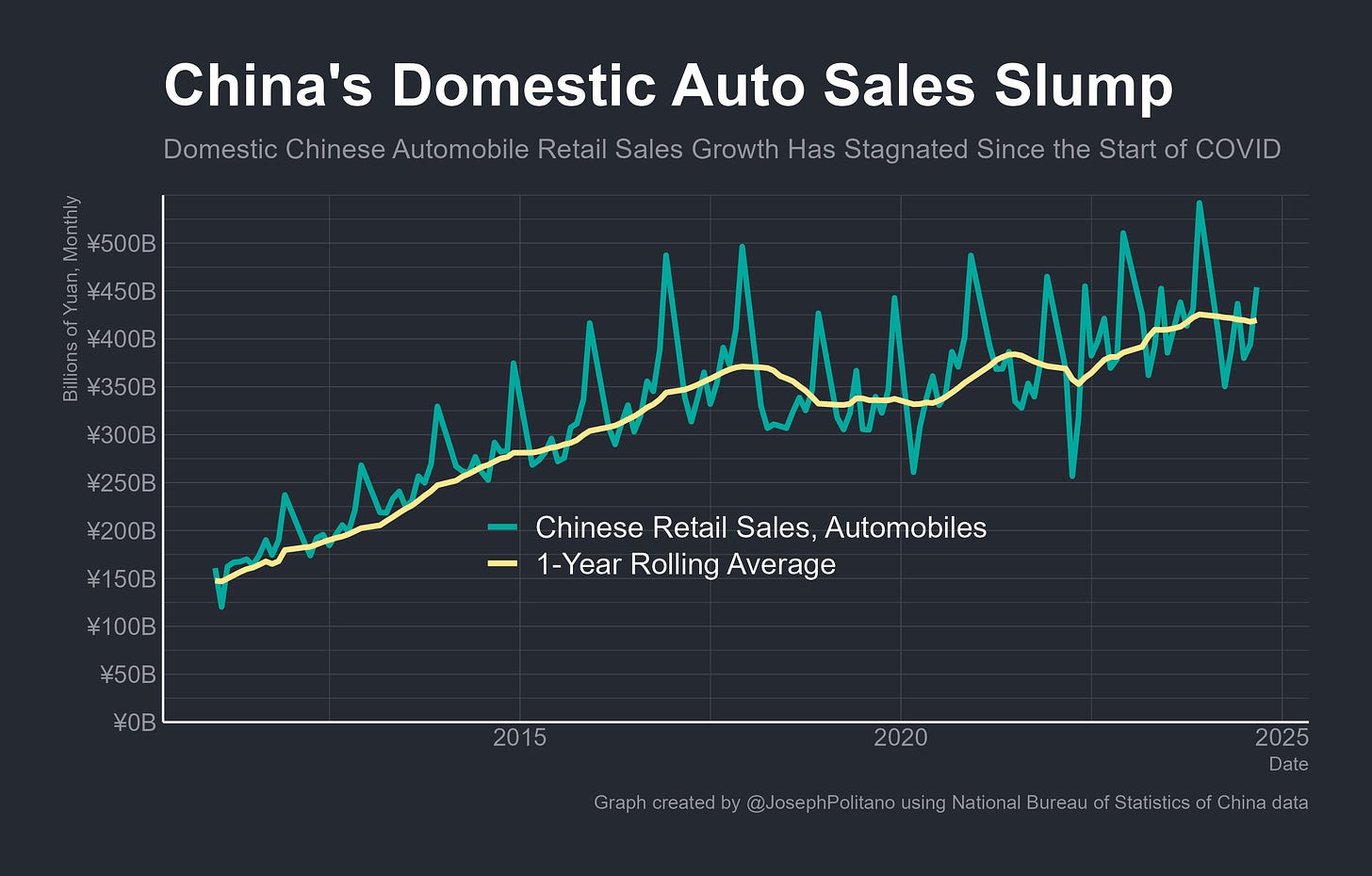

Yet Chinese consumers continue to suffer from a slow post-COVID recovery, struggling property market, and the country’s structural economic imbalances—leaving their demand for new vehicles tepid at best. Over the last seven years, nominal Chinese domestic retail sales of automobiles have only grown by 17%, down tremendously from the 160% growth seen in the seven years prior. Amidst the historic boom in NEV production, overall Chinese vehicle production remains only slightly above the previous record highs seen in 2018, and the raw number of vehicles sold domestically remains below those peaks. In other words, there is significant underconsumption relative to the nation’s existing manufacturing capabilities.

Despite this, investment by Chinese carmakers in yet more manufacturing capabilities continues to grow, with spending on fixed assets 5.8% higher than in 2023 and 27% higher than in 2022. That has rapidly increased the amount of spare capacity in the system—so far in 2024, capacity utilization in the Chinese automotive sector has dropped to the lowest level since data collection began three years ago—and has likewise enabled a much larger share of production to be sent abroad. Thus, rapid innovations in the EV market and weak domestic demand have rapidly transformed China from a net importer of finished motor vehicles into a net exporter.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.