The Eurozone's Unique Inflation Crisis

Inflation May be Global—But the Eurozone's Price Problems Remains Fundamentally Unique in the Wake of Russia's Invasion of Ukraine

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 19,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

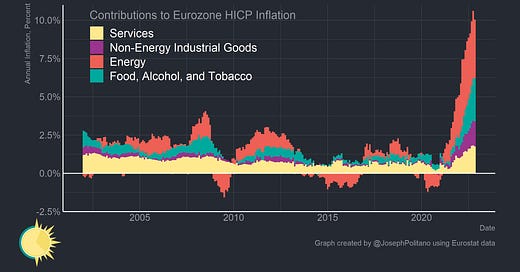

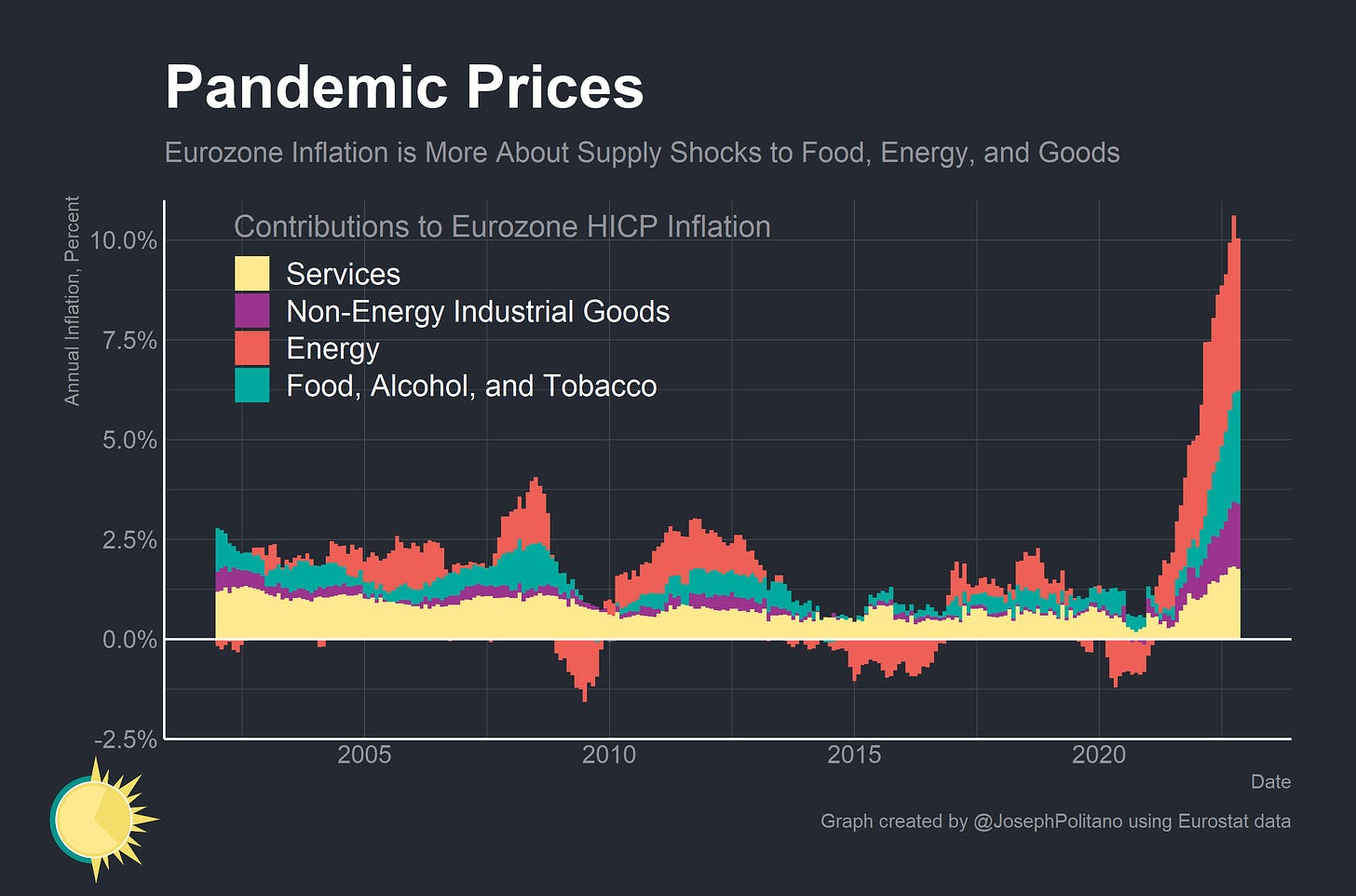

Inflation is now an ongoing global crisis, with many countries experiencing rapid price growth and the vast majority of central banks raising interest rates in an effort to curb aggregate demand. But though the crisis may be global, the underlying drivers of inflation aren’t as uniform as they first appear—particularly in Europe, which has been hit the hardest by ongoing energy, natural gas, food, and other large supply shocks in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. At a time when American inflation is now largely driven by cyclical or demand-sensitive components like housing and labor-intensive services, Eurozone inflation is still driven mainly by rapid price increases in components like food, energy, and manufactured goods that are more representative of supply shocks than excess demand1.

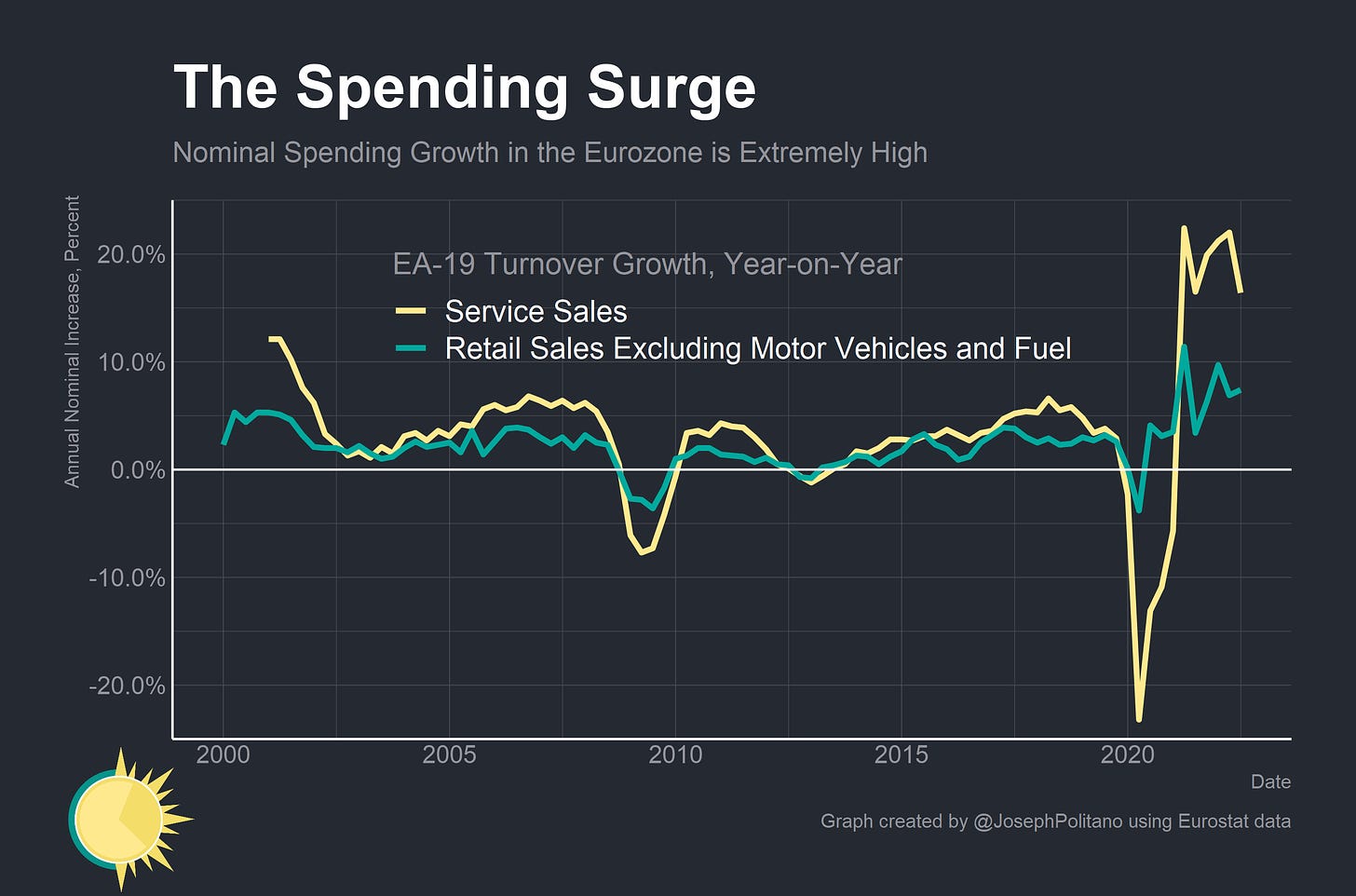

Indeed, aggregate nominal spending in the Eurozone still remains below the pre-COVID trendline even as American spending vastly exceeds what would have been expected in the absence of the pandemic. In simple terms, Eurozone inflation is less about too much money and more about too few goods—hence why the bloc’s inflation problem remains fundamentally different and why the intensity of monetary tightening in the US may not be appropriate across the pond.

However, it is true that the distinction between European and American inflation is increasingly a difference of degree and not of kind—nominal spending growth across the Eurozone is uncomfortably high, as are price increases in the more cyclical parts of core inflation and the short-term inflation expectations embedded in current financial market pricing. The big question that remains is whether the European Central Bank can tighten policy enough to prevent a further broadening of inflationary pressures without causing a continent-wide recession.

Monetary Policy in an (Energy) Shortage Economy

The obvious driver of Europe’s historic surge in energy prices has been the rapid rise in natural gas and electricity costs after Russia drastically reduced flows through natural gas pipelines linking the country to the EU. Alone, energy prices contribute nearly 3.8% to headline Eurozone Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) inflation—and that is despite various price regulations and previously-signed contracts keeping prices somewhat contained. But the energy shortage has also undoubtedly had a knock-on effect on prices in other categories, and the war-driven supply chain disruptions are not limited to energy either.

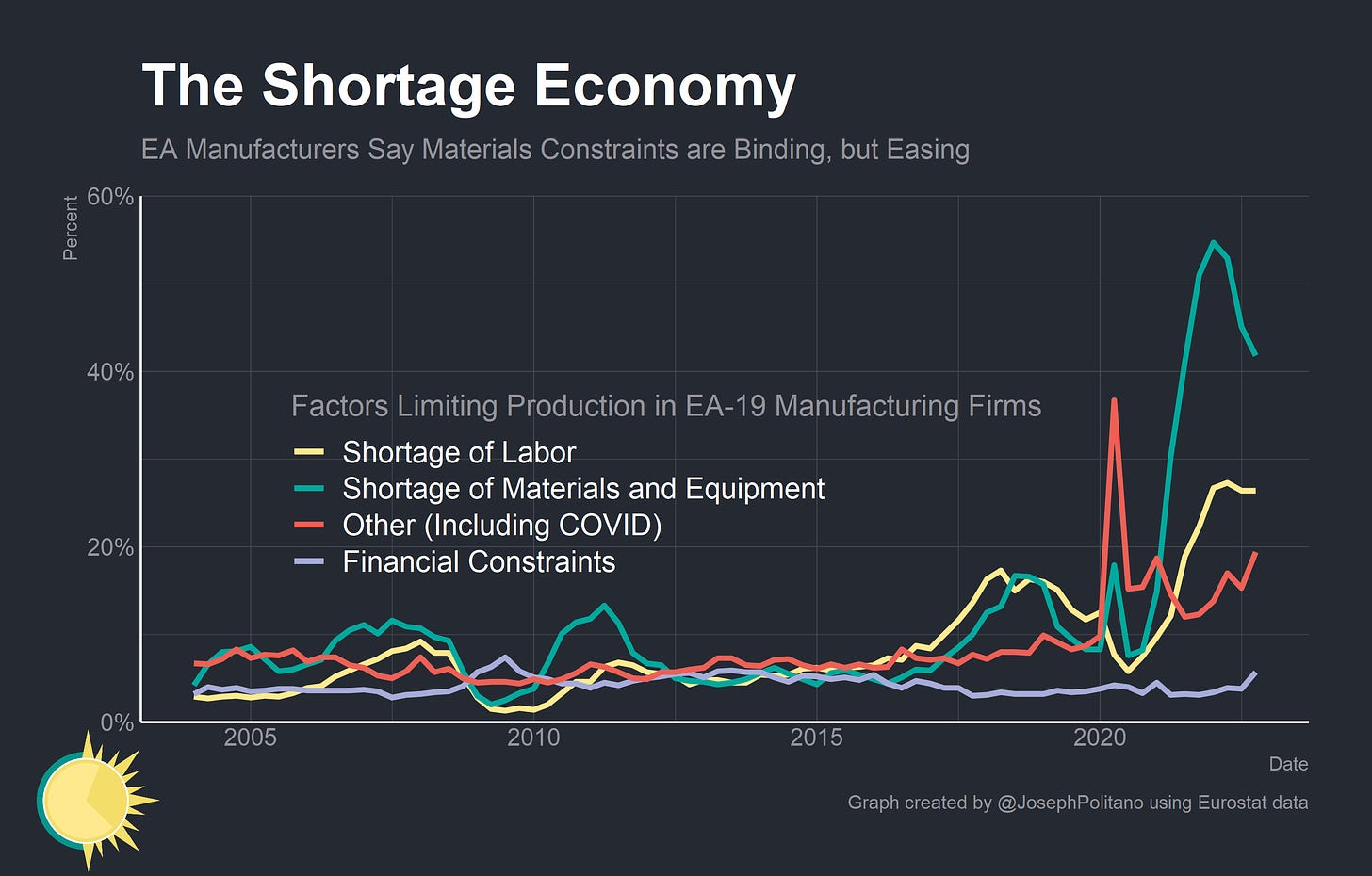

For example, the share of Eurozone manufacturing firms citing materials shortages as a main constraint on production hit an all-time high of nearly 55% just as the Russian invasion began, and has tempered slightly to just under 42% by the end of this year. Both of those numbers would have been record-highs by a wide margin at any point before the pandemic—showing just how big today’s supply-chain challenges are. In aggregate, European manufacturing output has held up despite the shock, but key sectors have suffered significant production hits.

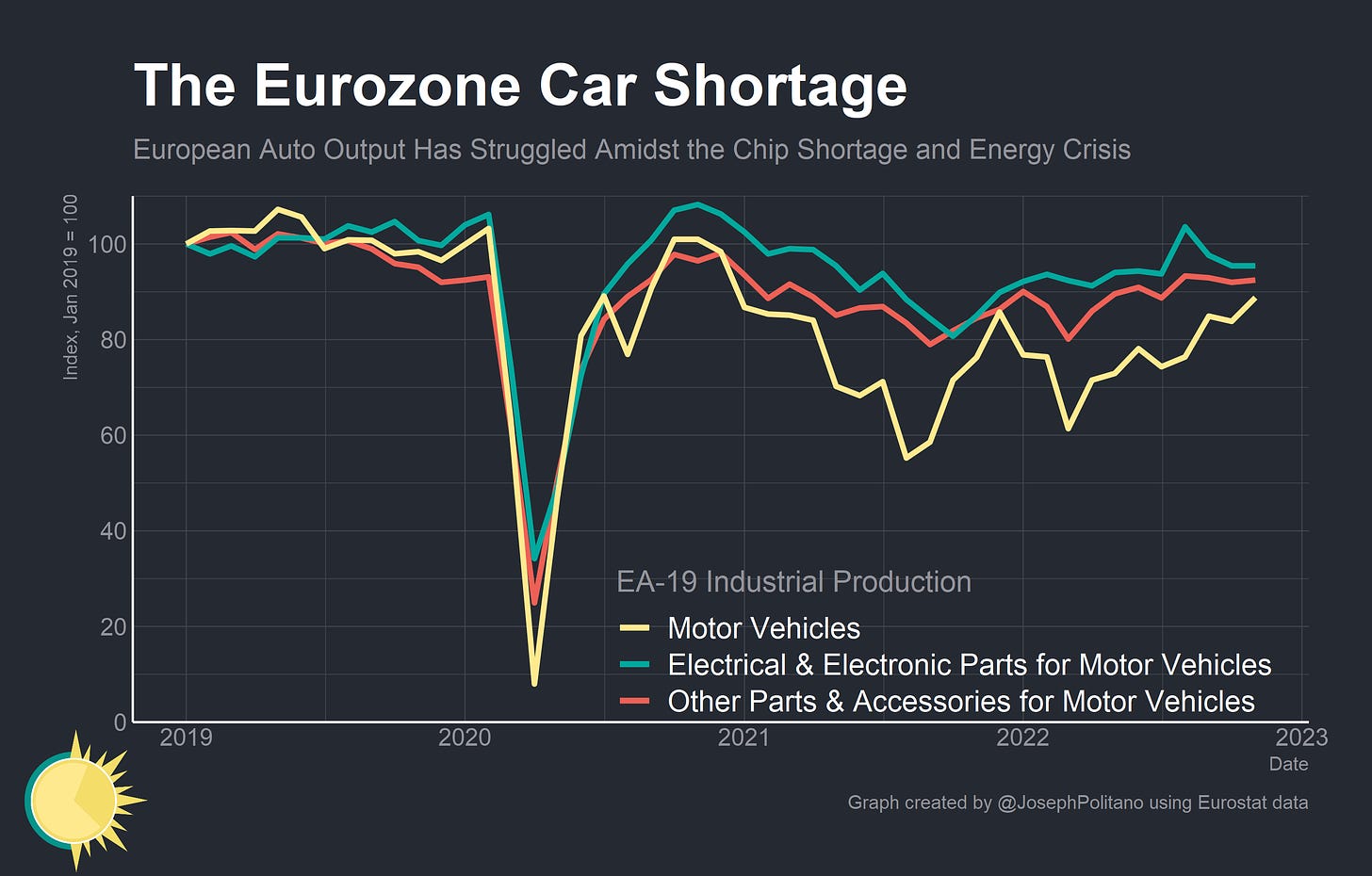

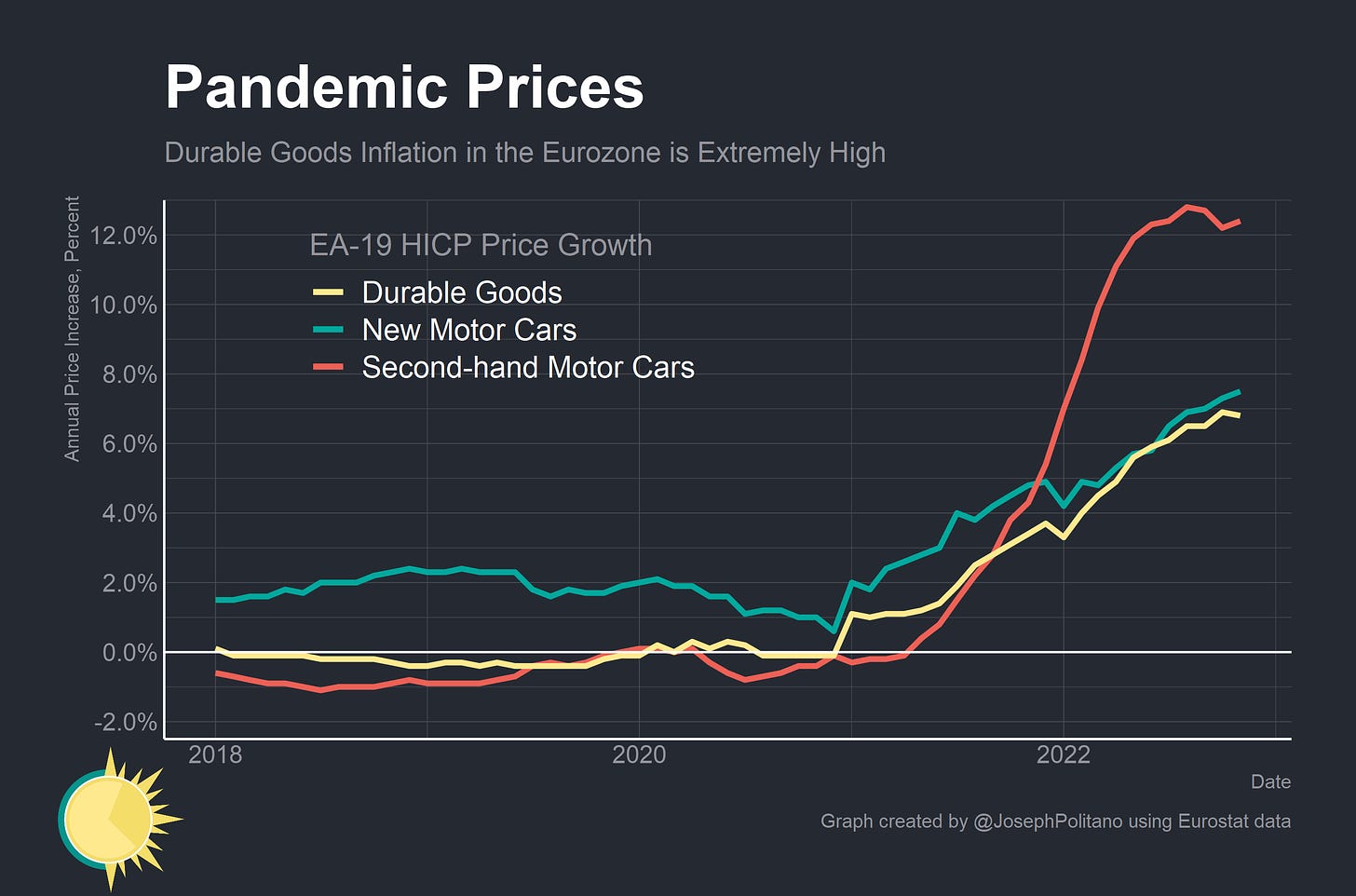

Take the recurring villain of global supply-chain-driven inflation: motor vehicles. After production dropped nearly 50% from pre-pandemic levels thanks to the semiconductor shortage, European automakers were able to stabilize their operations and then largely recover by the beginning of 2022. Disruptions from the invasion and ongoing input shortages sent production falling again, and only recently has output been able to catch up to about 90% of 2019 levels—leaving a massive cumulative production shortfall that is still growing.

Contrast that with the current situation in the US, where production has largely returned to normal levels and could start chipping away at the order backlog soon. As a result, European vehicle prices have been skyrocketing, especially for used cars, even as American vehicle prices are stalling or shrinking.

Still, while the massive increases in food and energy prices are not driven by aggregate demand or monetary policy, there are increasing pressures from cyclical growth that are pushing up cyclical inflation throughout the Eurozone. Record shares of service-sector and manufacturing-sector firms are citing ongoing labor shortages as their biggest problems, which could drive price increases through demand-pull and cost-push effects if the situation is exacerbated.

The Core Problem

There is one important way in which European and American inflation is relatively similar—the extremely large level of nominal spending growth they’ve experienced over the last year. While Euro Area nominal gross domestic product (NGDP) may be below trend, it has still grown a hot 6.7% over the last year—a number higher than the bloc experienced at any time from the creation of the Euro to the COVID pandemic. In the service sector, the growth is even starker with nominal sales rising by more than 15% over the last year.

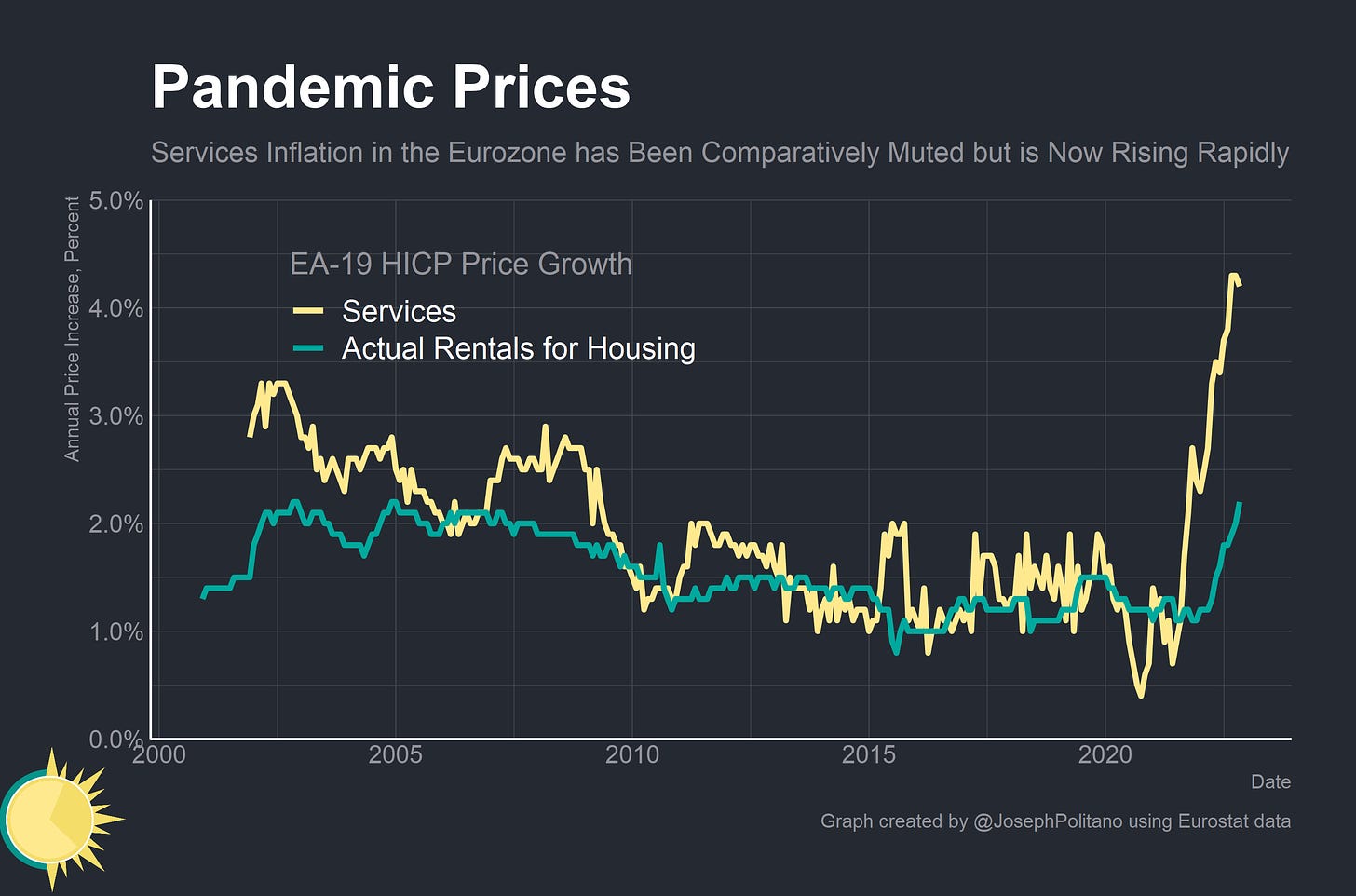

That rapid nominal spending and income growth are starting to show up in core services prices—which have also just hit their highest growth rate since the founding of the Euro. Even rent prices, which lag significantly and have more stringent price regulations than in the US, are achieving new record highs. These are the type of price increases that pose a more important threat to the European Central Bank (ECB)’s inflation mandate, and they are part of the reason why the ECB’s Governing Council has been looking to aggressively tighten monetary policy in order to combat inflation despite the fact that most of Eurozone inflation resides in sectors that are not usually strongly affected by monetary policy.

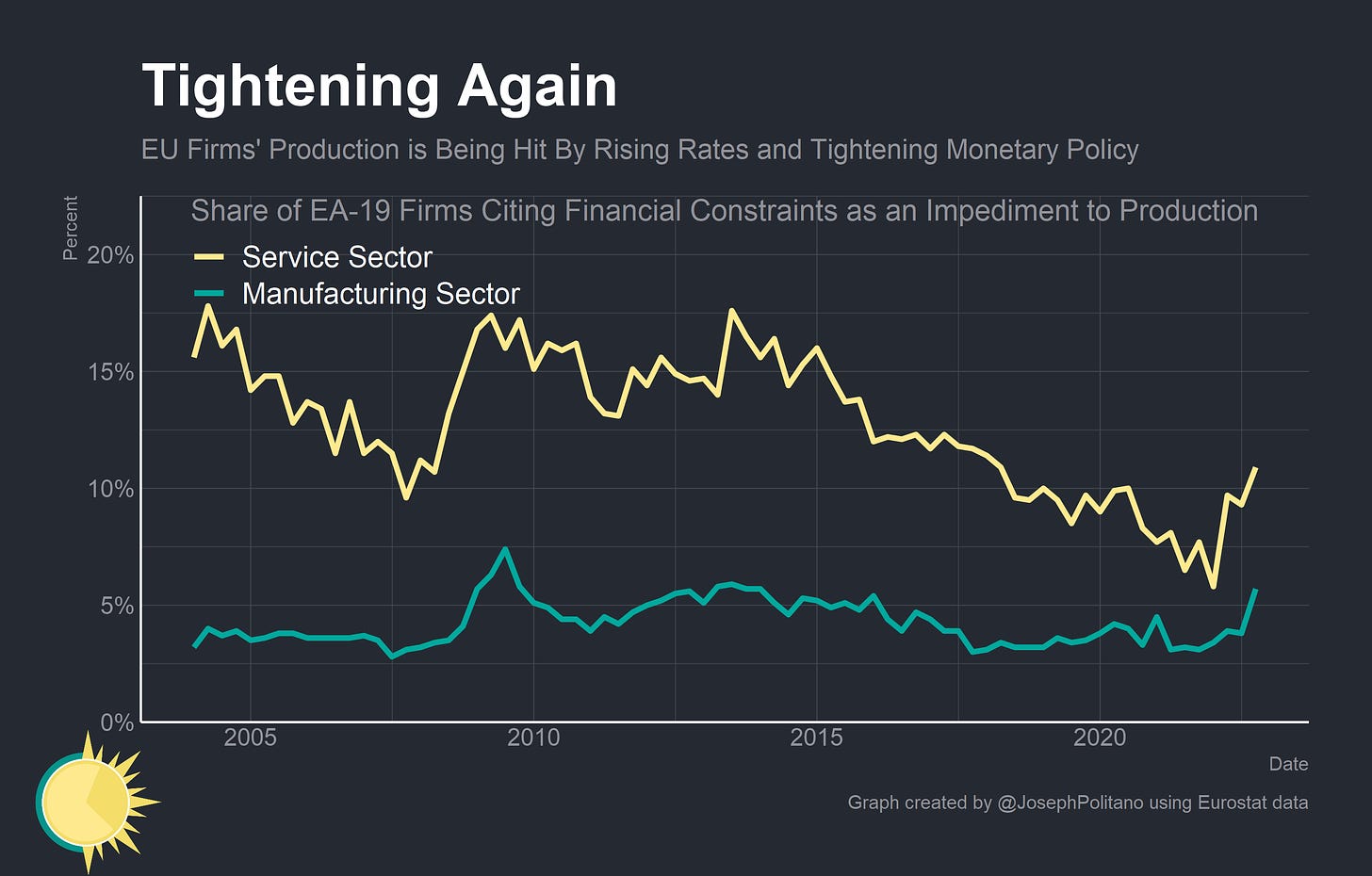

So can we see the effects of monetary tightening in the Euro Area yet? Besides the direct short-term effects of tightening financial conditions, we could be starting to see the effects through a decline in real demand. The share of manufacturing firms operating below capacity thanks to insufficient demand has been rising significantly since the second quarter of 2022, and the share of service-sector firms in the same position has bounced up a bit from near-historic lows. In other words, firms are becoming more demand-constrained as monetary policy tightens.

We’re also seeing a significant increase in the number of firms citing financial constraints as their main obstacle to production—especially in the service sector, which has historically been more sensitive to credit conditions throughout the business cycle.

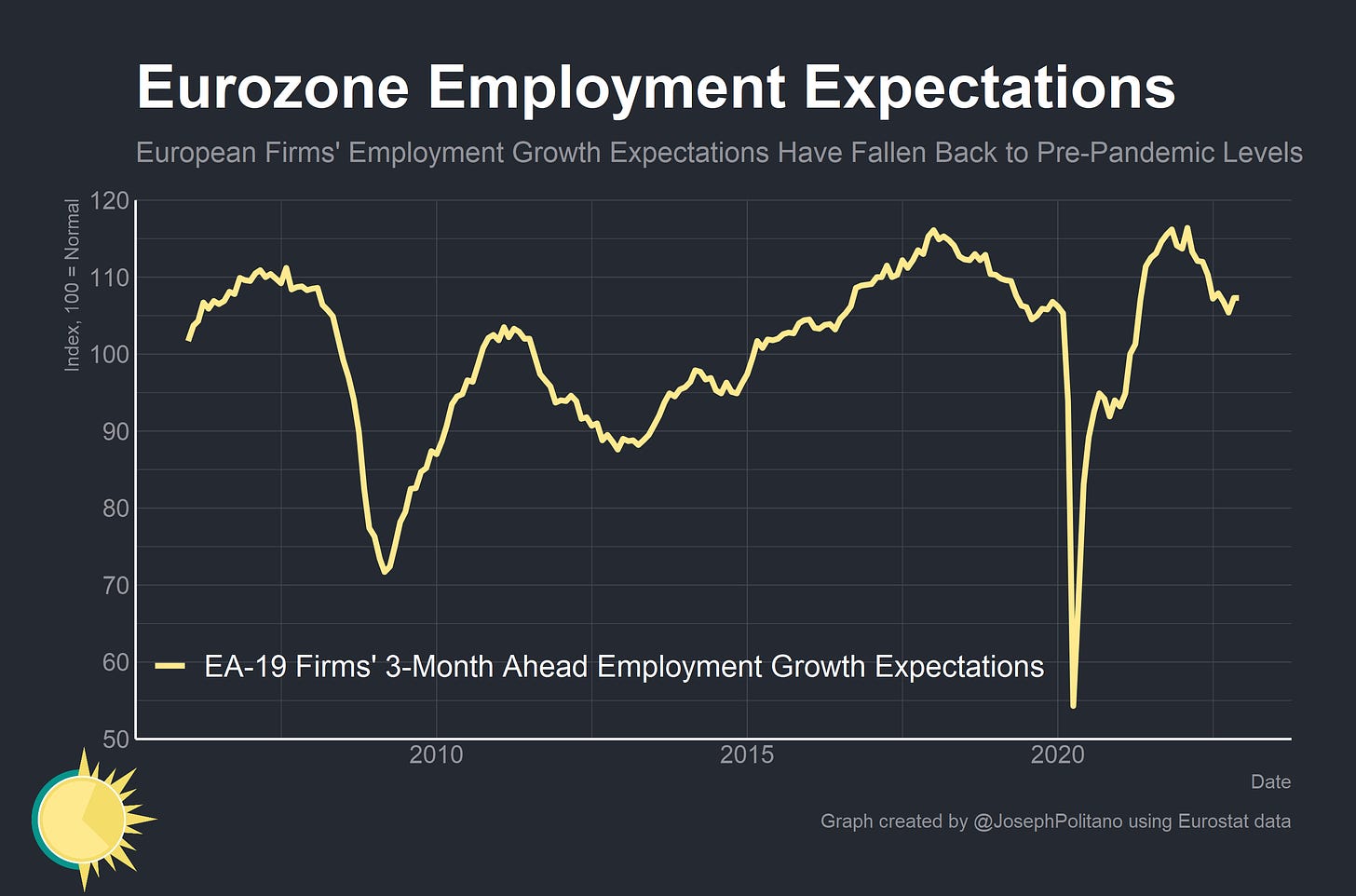

However, what’s most important is arguably the effects monetary tightening is having on the labor market directly—since the start of the year, Euro Area firms’ employment growth expectations have sunk dramatically and are now back to being roughly even with pre-pandemic levels. Q3 of 2022 also saw a worrying decline in prime-age employment rates across the Eurozone—the first of its kind since 2020—which pulled the bloc below its record-high employment rate in the prior quarter.

The weakening labor market is especially acute in manufacturing and retail, as firms in the latter sector actually expect to see payrolls shrink over the next quarter. The net deterioration this year, however, has been broad-based and relatively evenly spread across most sectors. Firms’ expectations are also relatively consistent with the ECB’s—right now, ECB staff forecasts expect employment levels to rise only marginally in 2023.

Conclusions

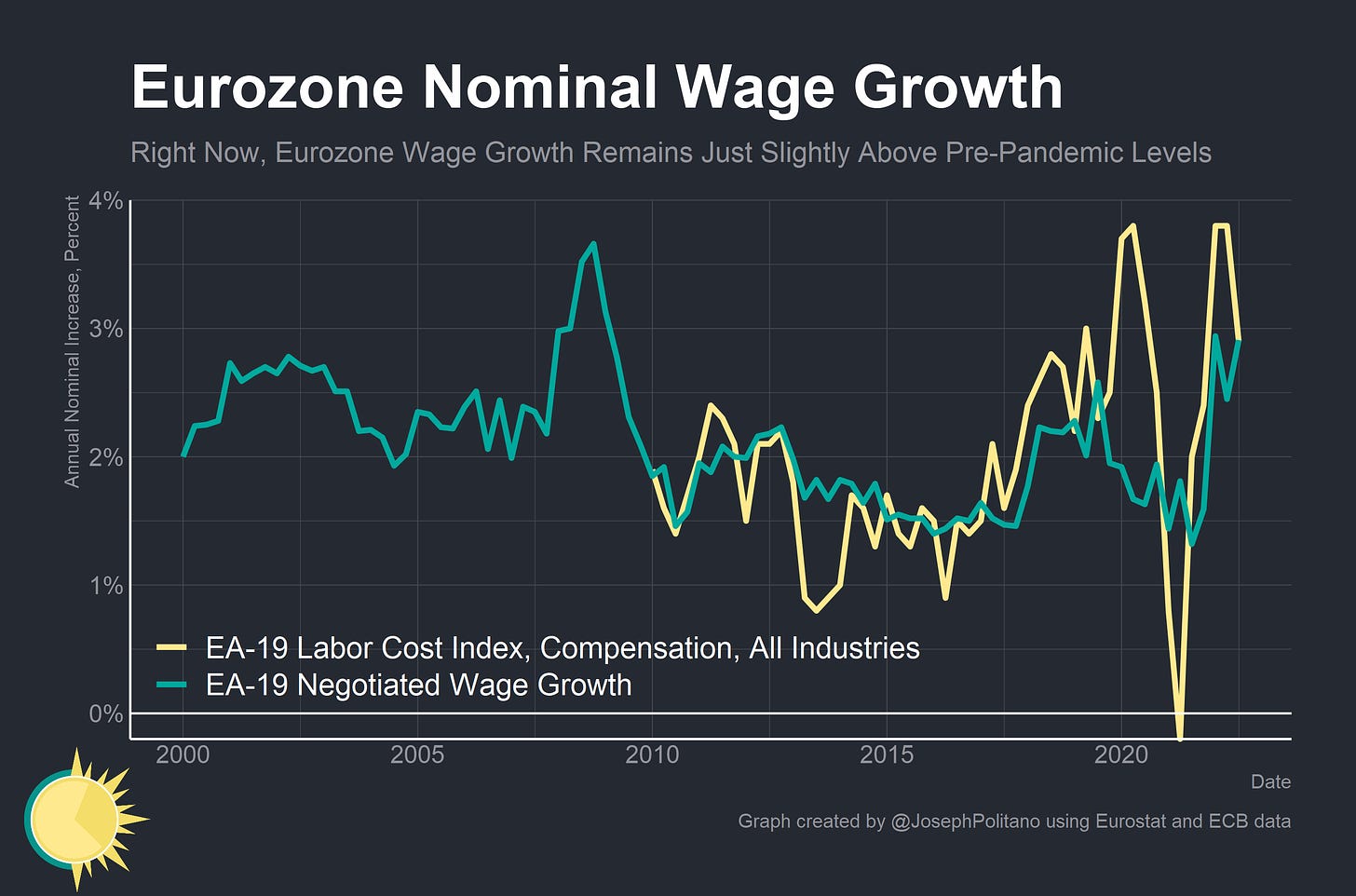

Fundamentally, the biggest difference between Europe's and America’s inflation situation comes from wage growth. Measured through negotiated wage growth or the labor cost index, Euro area wage growth has remained tempered, below 4%, and in line with pre-COVID levels as American wage growth set new records. Growth in listed wages on job postings in the Euro Area was 5.1% over the last year and less than 2% the year before that according to Indeed—compared to practically two years of above-6% growth in the US. And an experimental ECB series created with microdata on newly-signed wage agreements estimates that the Eurozone will see just over 2.5% wage growth over the next year (although newly-assigned agreements in Q4 had an average of 5% wage growth, and cost-of-living-adjustments play a more important role in European wage-setting than in America).

That lower wage growth makes it harder to justify that the same degree of monetary tightening is suitable in Europe as in America—fundamentally, European inflation has less to do with cyclical economic strength than America’s, and the Eurozone economy is in a more precarious position than America’s. It’s still a tough tightrope act to balance, however—doing too little risks entrenching core inflation, but if economic conditions continue deteriorating there is a major risk that Euro area economies will continue their decades-long underperformance that has led to longer-term economic stagnation.

Cross-country inflation comparisons are always messy, particularly between European HICP and US CPI because of how American data incorporates rents for homeowners. Take the direct cross-country comparisons in this piece as an important general point more than a complete quantitative analysis.