The EU's Different Inflation Problem

Europe Has A Different Inflation Problem Than the US—One that Demands a Different Solution

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Thanks for reading. If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 6,500 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

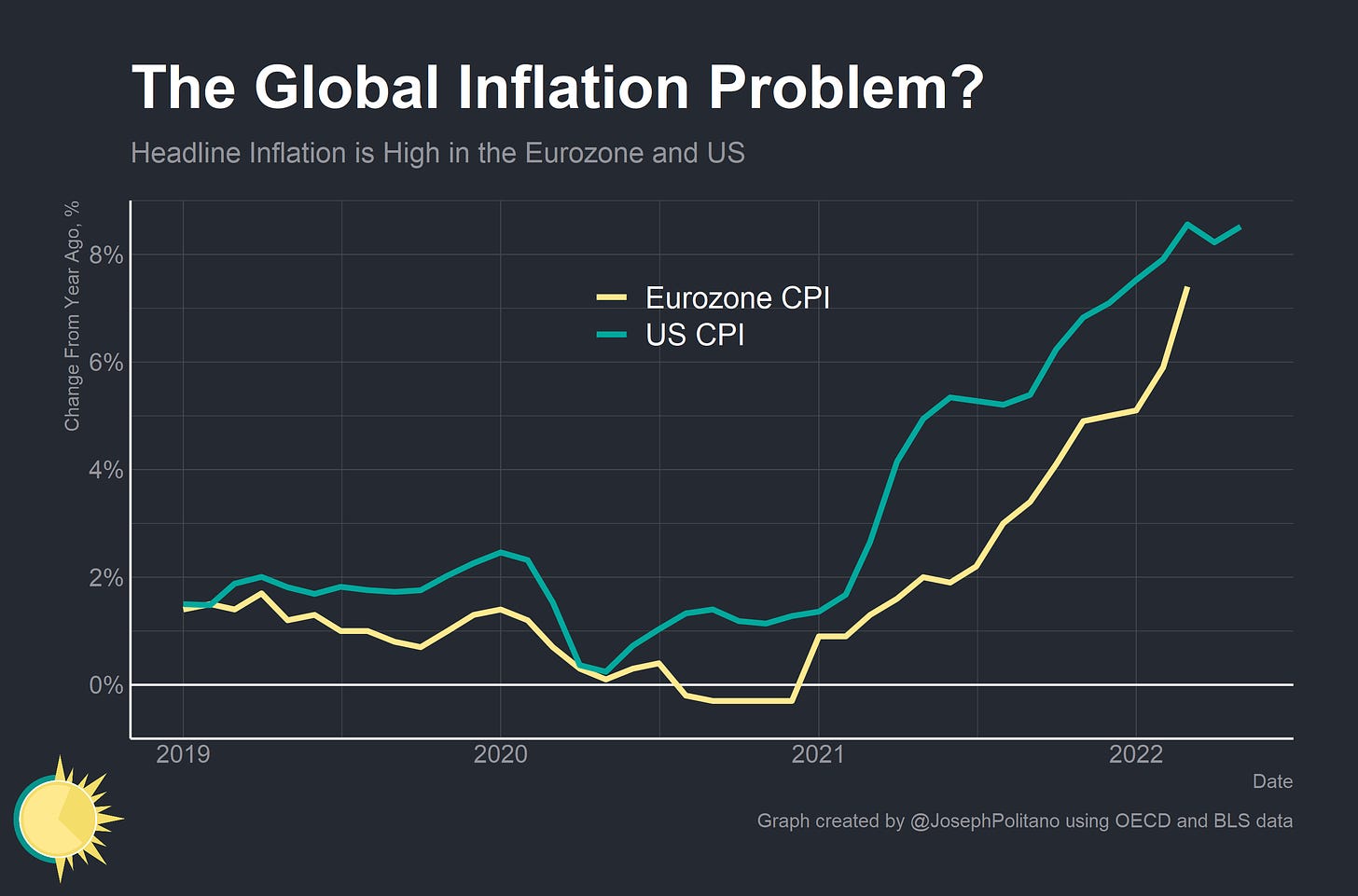

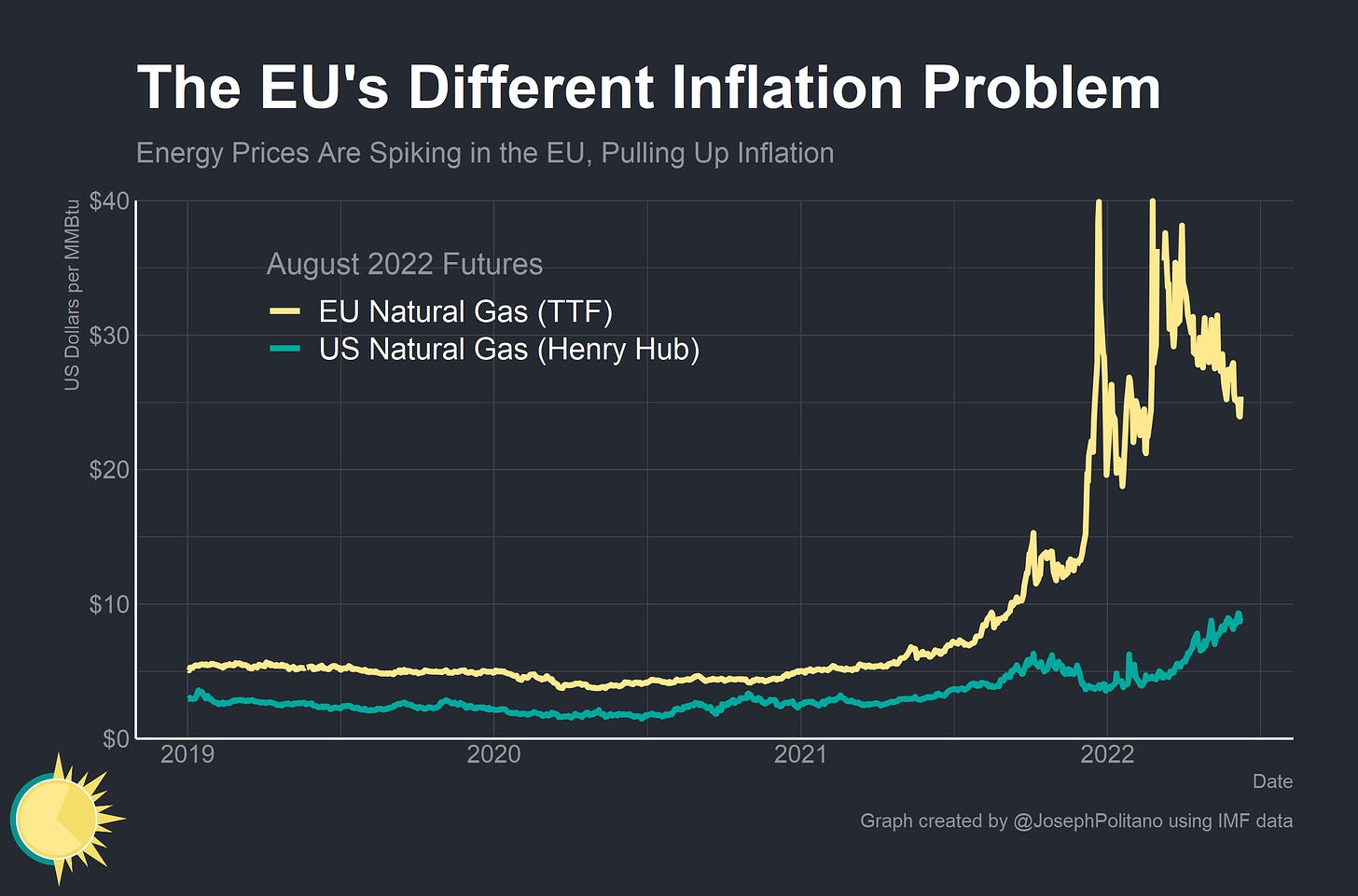

Yesterday’s Consumer Price Index release showed US inflation clocking in at 8.6% over the last year, remaining near the highest level in 40 years. At first glance, countries across the pond are experiencing the same problem— inflation in Spain is 8.3%, inflation in Germany is 7.4%, inflation in Italy is 6.9%, and inflation in France is 5.8%. March headline year-on-year CPI inflation was an eye-watering 7.4% across the Eurozone, the highest rate since the currency union’s creation.

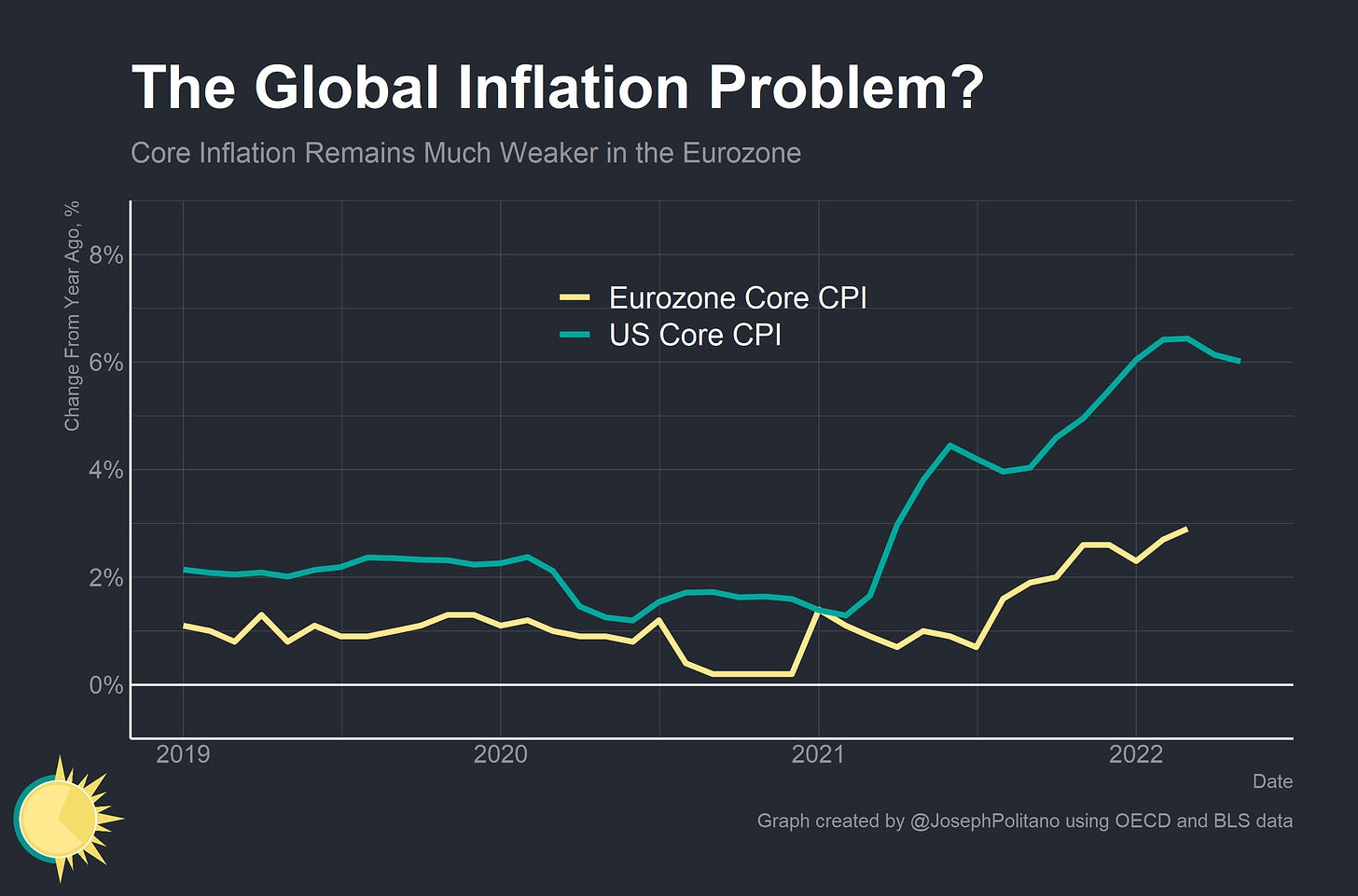

But headline figures belie important differences in inflation dynamics between the two continents. US inflation is relatively broad based, with high price increases across a variety of categories and in traditionally non-volatile components like housing. Eurozone inflation is much more concentrated in volatile sectors like food and energy which have experienced extreme supply shocks over the past year. Indeed, core CPI (which excludes food and energy) is running three percentage points lower in the Eurozone than in the US.

Of course, apples-to-apples comparisons of consumer prices across countries is extremely difficult. Every country’s domestic markets are structured differently and every country’s statistical agency calculates consumer price inflation using different inputs and methods. Former CEA chair Jason Furman and team have worked to calculate US inflation using the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) methodology employed within the EU, and he also finds a 2.7% difference in core inflation rates between the US and Eurozone1. Critically, energy costs have contributed about 2% to headline annual inflation in the US and 4% to headline inflation in the Eurozone. There’s also a reasonable point to be made that US motor vehicles represent an idiosyncratic inflation shock similar to energy in the Eurozone, but US motor vehicles’ contribution to headline inflation was about half the size of energy’s contribution to Eurozone inflation (and the motor vehicle price shock primarily occurred over a year ago at this point). These inflation comparisons will always remain imperfect, but they are the closest to apples-to-applies that we can get—and they clearly indicate that the Eurozone’s inflation problem is fundamentally different from America’s inflation problem.

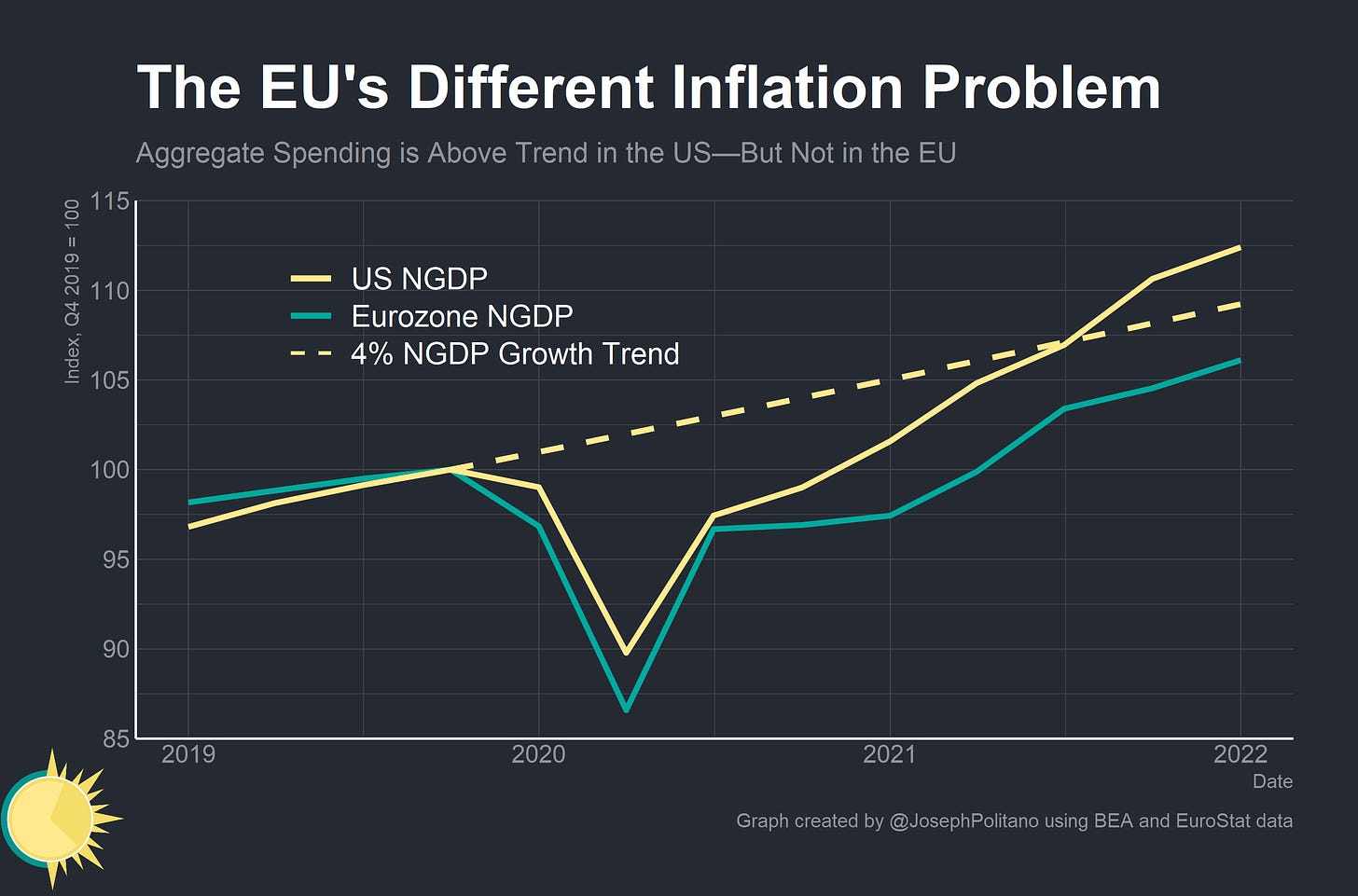

Additionally, if you back up and look at nominal gross domestic product (NGDP)—the sum of all spending in the economy—it becomes clear that aggregate demand has exceeded the pre-COVID trend in the US but undershot the trend in the Eurozone. It’s also true that NGDP growth in the Eurozone was too low before the pandemic—unemployment remained too high and inflation remained well below the ECB’s 2% target for more than a decade.

If excess aggregate demand is not to blame for inflation in the Eurozone, the blame must fall instead to supply shocks. And indeed, the EU has experienced unprecedented supply shocks over the last year, especially in the energy sector. That shortage of energy—particularly natural gas—was only exacerbated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The bad news is that those costs have still not completely passed through to consumer prices, so energy will remain a key driver of Eurozone inflation going forward.

The European Energy Crisis

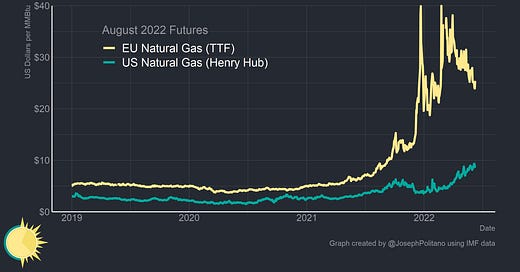

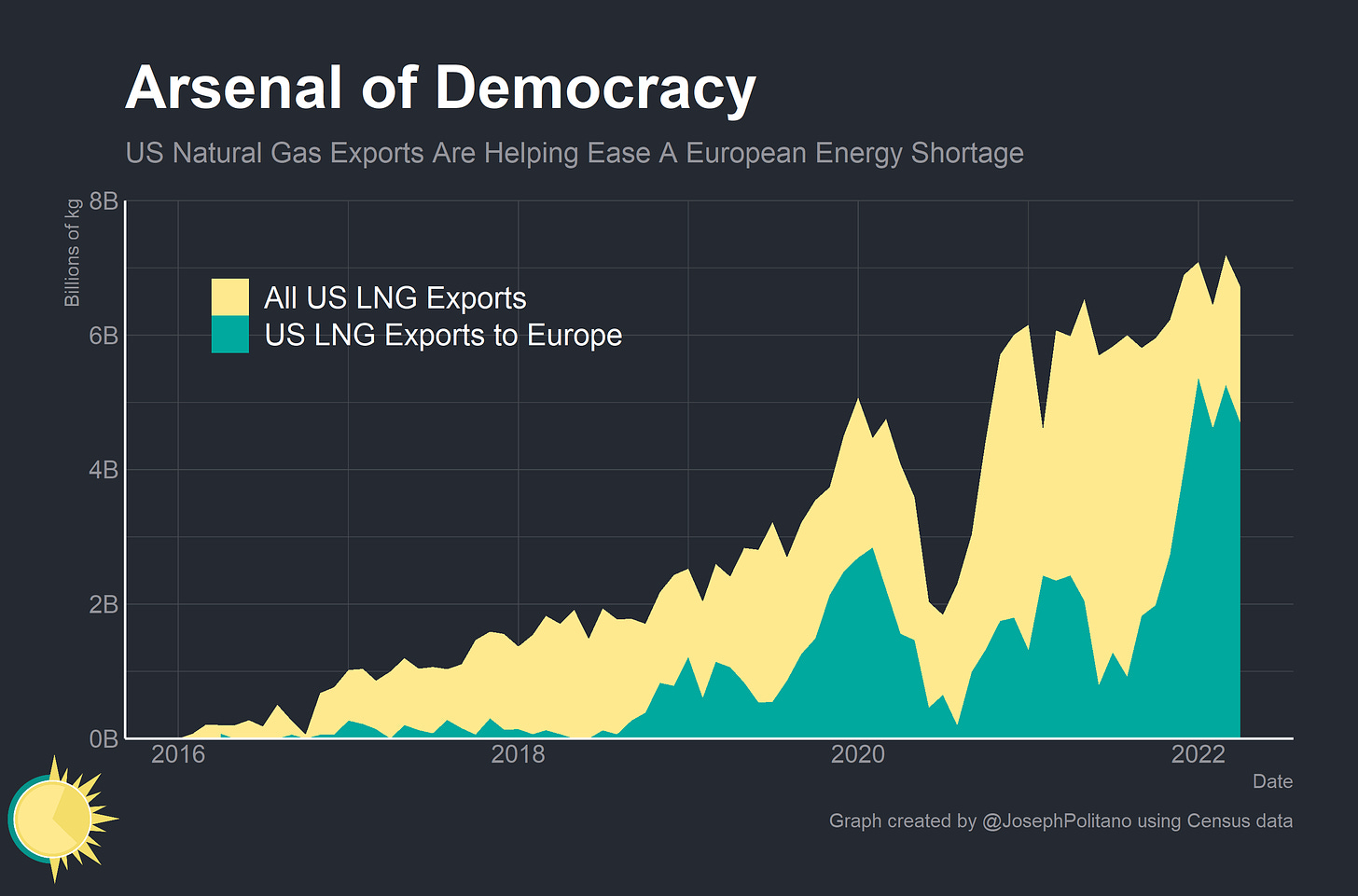

European natural gas prices started climbing midway last year as Russian exports started to wane and European gas inventories shrank. Prices have only continued climbing since then—demand is fairly inelastic as many Europeans use natural gas for household heating and it’s difficult for additional supply to come online given the physical infrastructure needed to move natural gas. Russia represented more than half of German natural gas imports in 2019, underscoring its importance to European energy supplies. Besides turning to smaller local producers like Norway, the only real option to replace Russian imports is through Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) shipments.

Indeed, that is exactly where Europe is increasingly turning. The US is liquefying a record amount of natural gas for transatlantic oceanic transport and nearly 3/4 of it is destined for European shores (note—this includes Turkey). Total US exports to Europe represent about 8.5 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d)—about 20% of total EU and UK consumption but not enough to replace the 13 Bcf/d of Russian exports to the EU in 2020.

That’s about where the good news ends, however. The US is at liquefication capacity right now and the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) projects that only another 0.8 Bcf/d of liquefication capacity will come online in the next year. On the flipside, Europe will struggle to accept sufficient LNG—The Economist catalogued the frantic efforts to rapidly install new regasification capacity across the continent. Germany lacks any regasification capacity at all, and most countries are turning towards floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs, essentially boats that act as regasification terminals) to bridge the gap. Freeport LNG, a terminal in Texas with the capacity to liquefy 2.14 Bcf/d, will be offline for at least three weeks following an explosion at the facility.

LNG demand from Asia had cratered following COVID lockdowns throughout China and Hong Kong, but that demand could come back if China reopens later this year. Indeed, August 2023 European TTF natural gas futures are trading only 10% below 2022 futures—which indicates that high prices are expected to stick for the next year2. Meanwhile, prices faced by many consumers—many of whom have one or two year fixed price contracts that will come up for renewal shortly—will continue rising even if spot natural gas prices stay stable. German think tank Dezernat Zukunft estimated that German households will lose an average of €221-€442 to increased electricity and natural gas costs in 2022 and another €472-€897 in 2023.

A Tale of Two Labor Markets

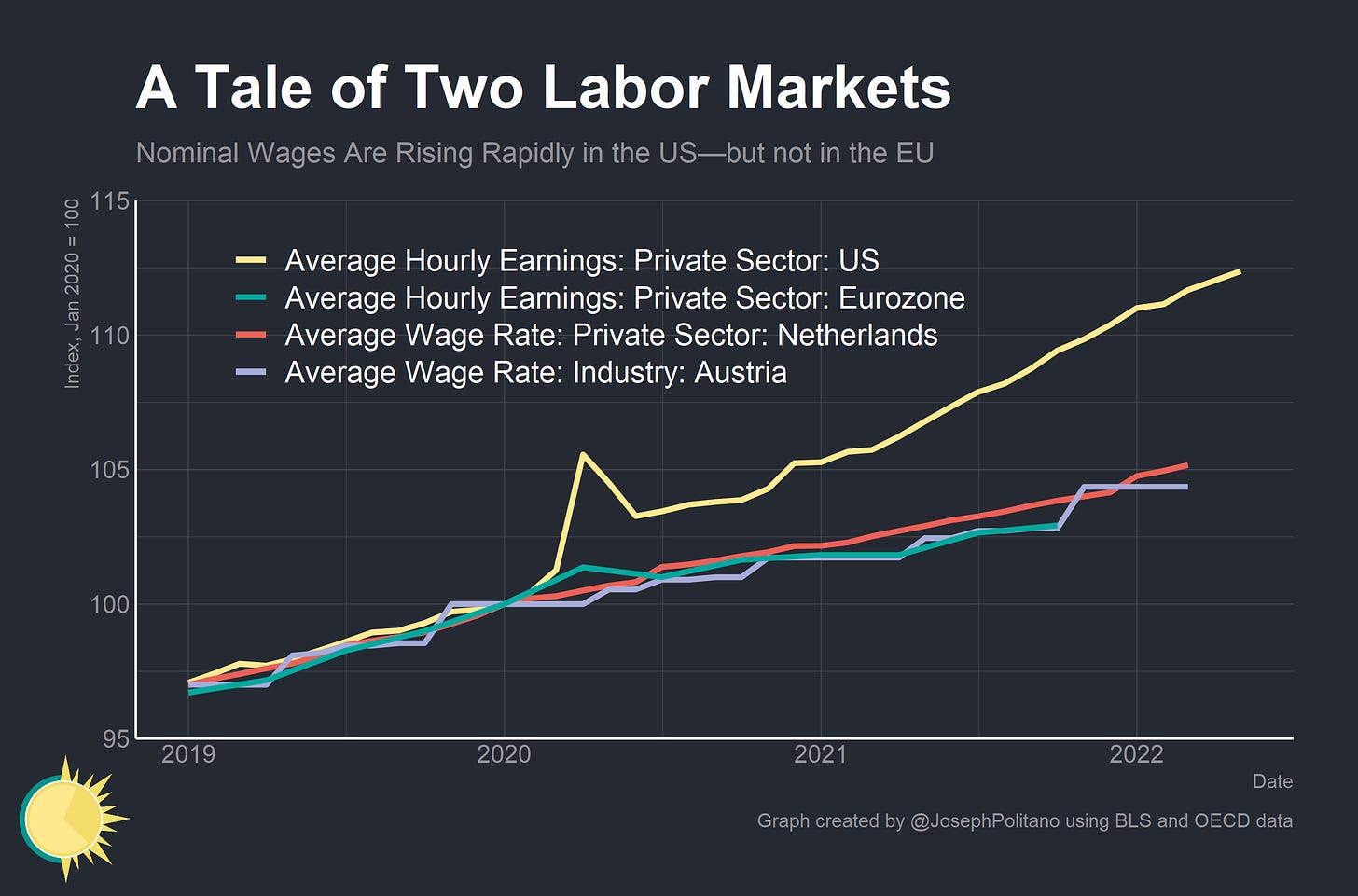

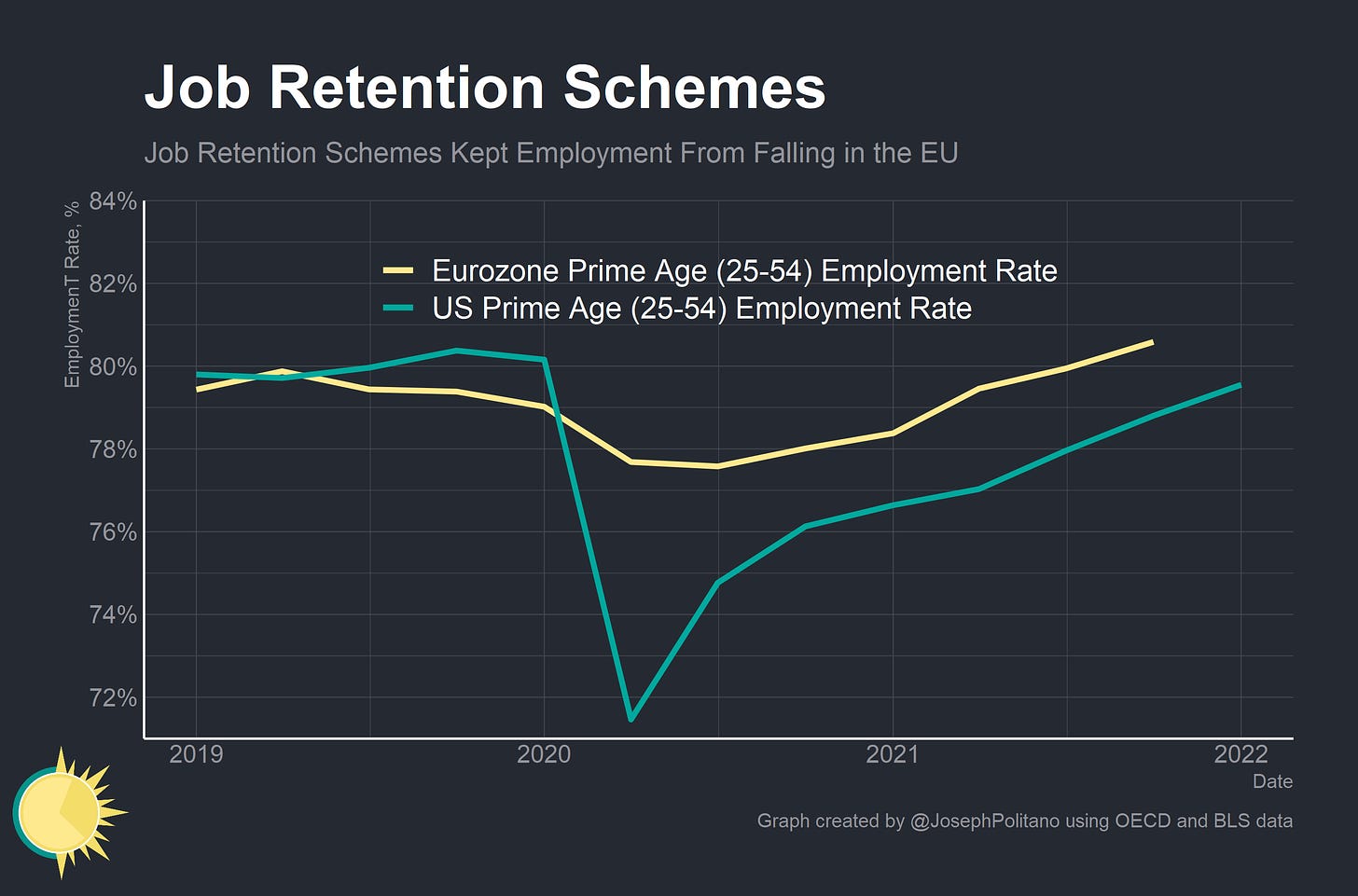

Switching gears back to aggregate demand, the Eurozone has ended up with the worst of both worlds in terms of growth and inflation. The US has stronger household balance sheets, rising incomes, and rapid real output growth coupled with inflation while the Eurozone has weaker wage and income growth coupled with equally high inflation. The wage data we have is, again, imperfectly comparable but still shows an important distinction—wages in the US are rising rapidly while wage growth has actually slowed down in the Eurozone.

This is likely the flipside of choices made at the beginning of the pandemic. European countries had the state capacity, quick responses, and government powers to institute job retention schemes that prevented employment from dropping quickly. The US lacked the ability to implement anything resembling a job retention scheme until the implementation of the Paycheck Protection Program—after millions of Americans had already been laid off. The result was that the US had to send out Trillions of dollars in direct stimulus and unemployment insurance in order to boost aggregate demand and bring employment back up—while most Eurozone countries didn’t. Now Europe is stuck with lower aggregate demand—and US employment rates are catching up to European levels.

When All You Have is A Hammer…

The Eurozone may have a different inflation problem than the US—but it is pursuing the same solution. The European Central Bank has announced plans for the first rate hike since 2011, even as it has downgraded its 2022 GDP growth forecasts by a full percent. The spreads between Italian/Greek and German bonds are rapidly increasing, indicating worsening financial conditions and a tougher borrowing environment for national governments. The same story is true for corporate borrowers, who are facing tighter financial conditions than in the US.

If European governments want to get serious about combating their unique inflation challenges they’re going to have to come up with a more unique policy approach. Germany should seriously consider following Belgium’s lead and extending the lifespans of its last remaining nuclear reactors—which are scheduled for shutdown this year. There are a plethora of legal, practical, and technical issues with this plan but it still represents a better alternative to increased coal power or further reliance on Russian natural gas. Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi’s idea for an energy buyer’s cartel could work well against Russia specifically—the same infrastructure that binds German natural gas to Russian imports also binds Russia to the German export market. Given Russia’s disregard for previously signed agreements, willingness to use its energy supplies as leverage, and deteriorating military and economic position there is space for the EU to negotiate—or demand—lower natural gas prices if they work together. More than that, the continent should double down on building energy trade infrastructure with the US—who likely represents the only friendly country with the capacity to shield the continent from an acute energy shortage. That—coupled with necessary renewable investment—is the only long-term way out of reliance on Russian imports.

The weaker aggregate demand picture also gives national governments more flexibility in supporting households through the crisis. Serious considerations should be made towards directing stimulus to low-income households in order to cover their rising utility bills. This could also counteract some of the downward growth impulses caused by the Russia shock and support a strengthening of the labor market.

The Eurozone’s economic performance since the late 2000s represents one of the modern world’s largest tragedies. The continent has suffered under more than a decade of extremely weak growth thanks to a long series of macroeconomic failures that left demand, employment, wage growth, and output permanently lower. The current inflation crisis represents another tough challenge for the continent’s economic policymakers—and they cannot afford to make more mistakes.

Sometimes in media you get the scoop, and sometimes you get scooped. In this case I got scooped; Jason Furman published a nice piece in the WSJ on the same topic (and with practically the same title!) while I was working on this. I would encourage you to read Jason’s piece, but I believe I had some valuable additions that justified publishing this piece to compliment his work.

It’s usually a bad idea to treat futures prices as market expectations of spot prices one year forward (as hedging and risk management play important roles in futures prices but not spot prices), however they can give a general idea of expected future spot prices. In this case, I wouldn’t go beyond saying that European natural gas prices are expected to decrease over the next year but remain high.

Very nteresting. Poor Europe. Your note 2. is very important as few commentators make the distinction. Prices in the Futurs Markets are TODAY assessments of prices for forward delivery or settlement, at which traders buy and sell. The really informative piece of information is the structure of futures markets, which may reflect expected oversupply (contango in physical goods) or scarcity (backwardation or inverses in grains)

Why is inflation in France so much lower than in the rest of the EU? It sounds like they are doing something right.