The EU's Fragile Recovery

The EU's Economic Recovery Has Been Slow and Weak—and is Increasingly at Risk

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 33,000 people who read Apricitas weekly

Today, nearly every EU member has seen its economic output fully recover from the depths of the pandemic, yet that recovery has been extremely slow and relatively weak overall. Major Eurozone economies—Italy, France, Spain, and Germany—have barely seen any growth in excess of 2019 GDP levels and have almost all seen their economic recoveries decelerate substantially over the last year. Recently, EU macro data has consistently surprised to the downside, German economic output has been either zero or negative across the last nine months, most recent Italian GDP data saw the economy shrinking 0.3% in one quarter, and Spanish GDP has only recently climbed above pre-pandemic levels.

Indeed, most of the major Eurozone economies are trailing the EU average significantly, even when you exclude the effects of tax-haven-driven growth in Irish GDP on EU-wide growth, and the bloc itself is trailing growth in high-income countries on other continents. The aftereffects of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are still being felt as energy and food prices, though stabilizing, remain high enough to hold back industrial output and increase precarity among many European households.

Indeed, rising prices combined with slow growth have forced many European households into tough choices. Real food spending across Germany, Italy, and France is now between 6-7.5% below pre-pandemic levels, representing a brutal cutback in essential consumption, especially for lower-income households, and serving as a stark reminder of the human costs of Europe’s weak economic growth.

This short piece is designed to give a broad overview of the situation in Europe and the high-level macroeconomic trends as the start of a series of articles on European economies. Upcoming pieces will focus on breakdowns of the detailed country-by-country dynamics alongside more specific discussions of the ongoing ripple effects of the war in Ukraine—but before delving into the nuanced detail, it's essential to understand the broader economic patterns that have been unfolding across the continent.

The Easing of Shocks

The good news is that much of the acute supply chain and energy shortages that plagued European manufacturers over the last two years are steadily fading. The share of companies citing materials shortages has declined to the lowest levels since the beginning of 2021, and the share citing “other” constraints—a catch-all that includes energy shortages and COVID restrictions—has fallen to the lowest levels since the start of the pandemic.

The bad news is that much of the decline in manufacturing constraints comes from a large weakening in demand over the last year. Indeed, European manufacturing firms expect to shed workers over the next three months for the first time since the initial pandemic shock—and the demand-side weakness has been particularly acute in Germany, where a large majority of industrial firms are now expecting to cut their workforces.

Leading indicators for European industrial activity likewise remain extremely poor—the stock of order backlogs is falling at a rate not seen since early 2020, and manufacturers’ own inventory levels are rising rapidly. Retailers are also cutting back on their purchases as inventory levels normalize and have consistently expected to cut their orders placed with suppliers for more than a year straight, again most acutely in Germany.

In the service sector, the situation looks somewhat better—the COVID restrictions and demand shortfalls that were keeping output low in 2020 and 2021 have mostly declined, replaced by rising labor shortages. Those labor shortages are good news for Eurozone workers and would be essential to maintain employment growth in the face of possible job losses in industry and other sectors—yet even here the higher-frequency data shows a less rosy picture, with service-sector employment growth expectations falling dramatically over the last three months.

In construction, the materials shortages that plagued the industry during the pandemic have now mostly abated alongside the drop in COVID-related output issues. In their place, concerns about labor shortages have also risen, which helped give construction the strongest employment growth expectations of any industry last month. However, there is a steadily increasing concern about construction financing as interest rates rise.

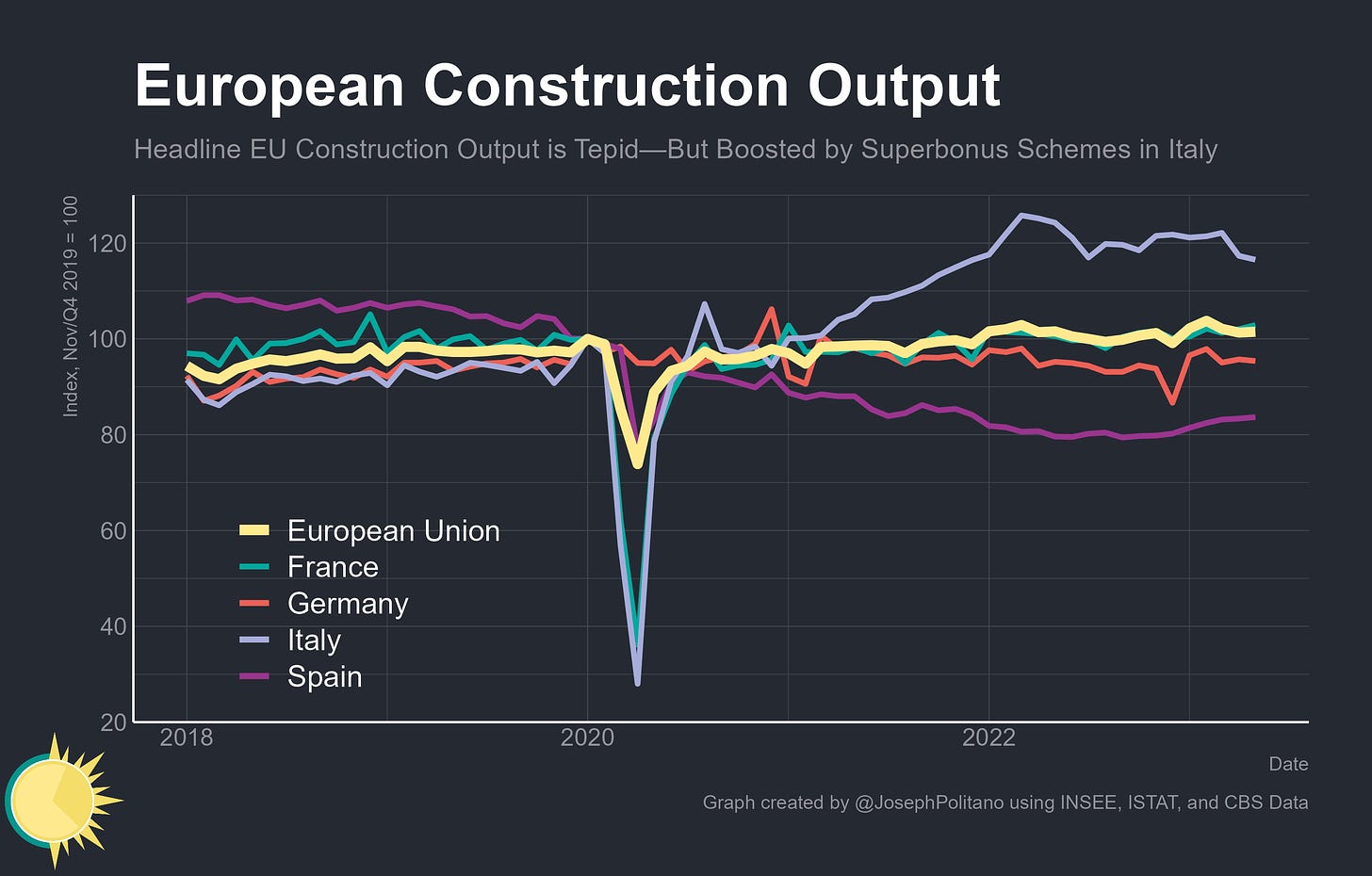

So far, higher interest rates have not cut too much into aggregate construction output, which remains roughly 1.5% above pre-pandemic levels. That does mask substantial variation amongst countries, though—Italy, with its generous and controversial Superbonus green home renovation tax credits, has seen a massive surge in construction output while Spanish output remains well below pre-pandemic levels.

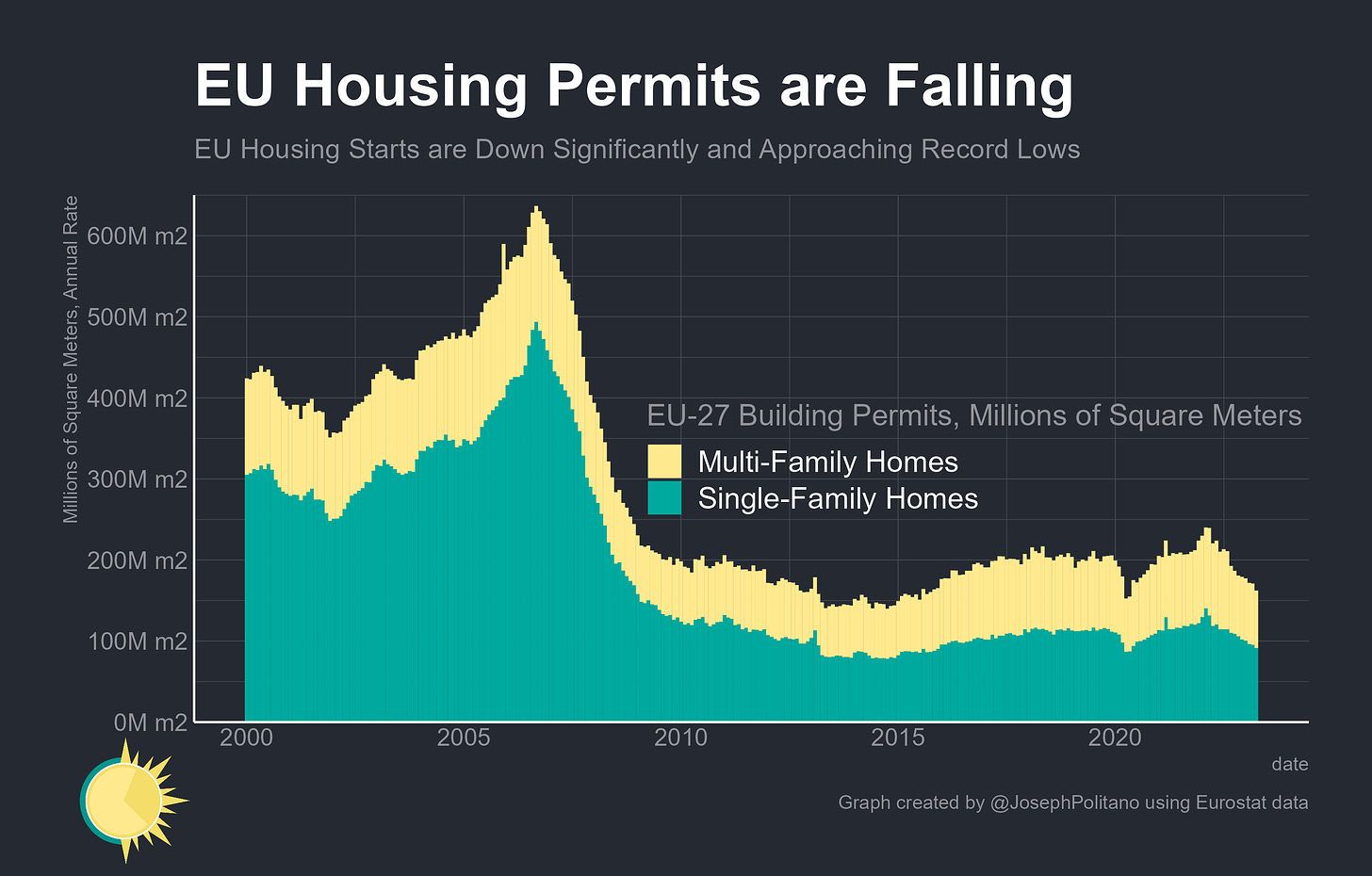

However, tighter monetary policy and higher mortgage rates are starting to have effects on new housing construction even as aggregate output remains strong. The square footage of newly permitted housing units in the EU has fallen to some of the lowest levels since the turn of the millennium, although the large backlog of projects started during the pandemic and the concentration of activity in remodeling/home improvements are providing somewhat of a buffer for the industry.

Conclusions

Housing isn’t the only place where tighter monetary policy is starting to show up as a drag on growth, however—across sectors, the share of Eurozone businesses that are struggling to access financing is rising and is now at levels not seen since the mid-2010s.

Likewise, the share of businesses reporting shortfalls in demand is up, especially in manufacturing and construction, where aggregate demand is now well below pre-pandemic levels.

Labor market growth expectations are also cooling across the continent, and are now actually slightly below their long-run norms in Germany. That dissipating labor market growth is perhaps the most worrying economic sign, as the EU has been able to avoid the absolute worst effects of recent shocks by virtue of maintaining strong employment growth in an inflationary environment.

Yet recent economic performance is also a reminder that low or slow growth, over long enough time periods, can cause significant deterioration in relative living standards even without an extreme recession. Since the start of the pandemic, US GDP per capita has grown more than 5% at a time when many European countries have seen negative or low GDP per capita growth—a gap that mostly emerged before the Russian invasion and partially enabled the US to better weather the wartime energy and food shocks. For the EU to keep hold of its fragile recovery, growth will have to accelerate again.

The link to Europa.eu for less rosy, higher frequency data is broken. It says, “There is no data available based on the selected criteria.” I suspect the criteria are saved in a session cookie or something, rather than in your URL.

The reason that the Polish economy is looking stronger is that the ruling party has been spending more freely, in hopes of buying electoral support.