Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 9,500 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

When America was founded nearly 250 years ago, the states remained famously disunited and the central government famously ineffectual. The original Articles of Confederation were scrapped for a Constitution that granted the Federal government more authority, but even after the Constitution’s signing most states retained sovereign authority over their finances. It wasn’t until 1790 that then-Treasury-Secretary Alexander Hamilton navigated a compromise allowing the federal government to assume states’ debts and issue its own obligations in their stead—an event dramatized in two songs from the Secretary’s eponymous musical.

Today, America’s federal government borrows and spends trillions easily. In fact, the country’s debt earns a significant premium thanks to the greenback’s dominant role in international exchange. States still borrow, but the vast majority of deficit spending comes from the Federal government at a unified series of interest rates determined by domestic monetary policy. Citizens in Illinois and New Jersey—the states with the worst credit ratings—have no more reason to fear the loss of essential government healthcare provisions like Medicare than citizens in states with perfect credit. Since the country issues its own currency, it has no risk of defaulting on its obligations—unless the nations leaders decide that extremely high levels of inflation is not preferable to default (a la Russia’s 1998 sovereign default). But America remains miles from even considering that choice—national debt burdens were near historic lows over the prior decade.

"The United States can pay any debt it has because we can always print money to do that. So there is zero probability of default"

Alan Greenspan, Former Chair of the Federal Reserve

When the European Union (EU) and European Central Bank (ECB) were created, it was clear that these supranational institutions would not be supplanting national authorities in the same way that the US Federal government and Federal Reserve supplanted state governments. There was no continent-wide fiscal union to redistribute trillions across national borders, there was little non-regulatory economic policy coordination between states, and countries still issued their own debts to fund their own operations. Critically, that central bank guarantee of sovereign government debt was not in place.

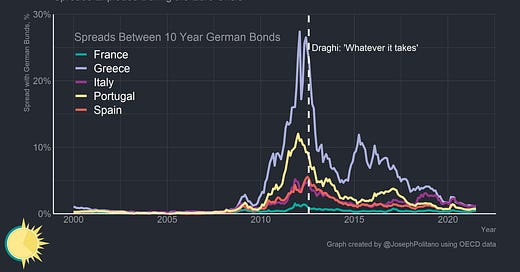

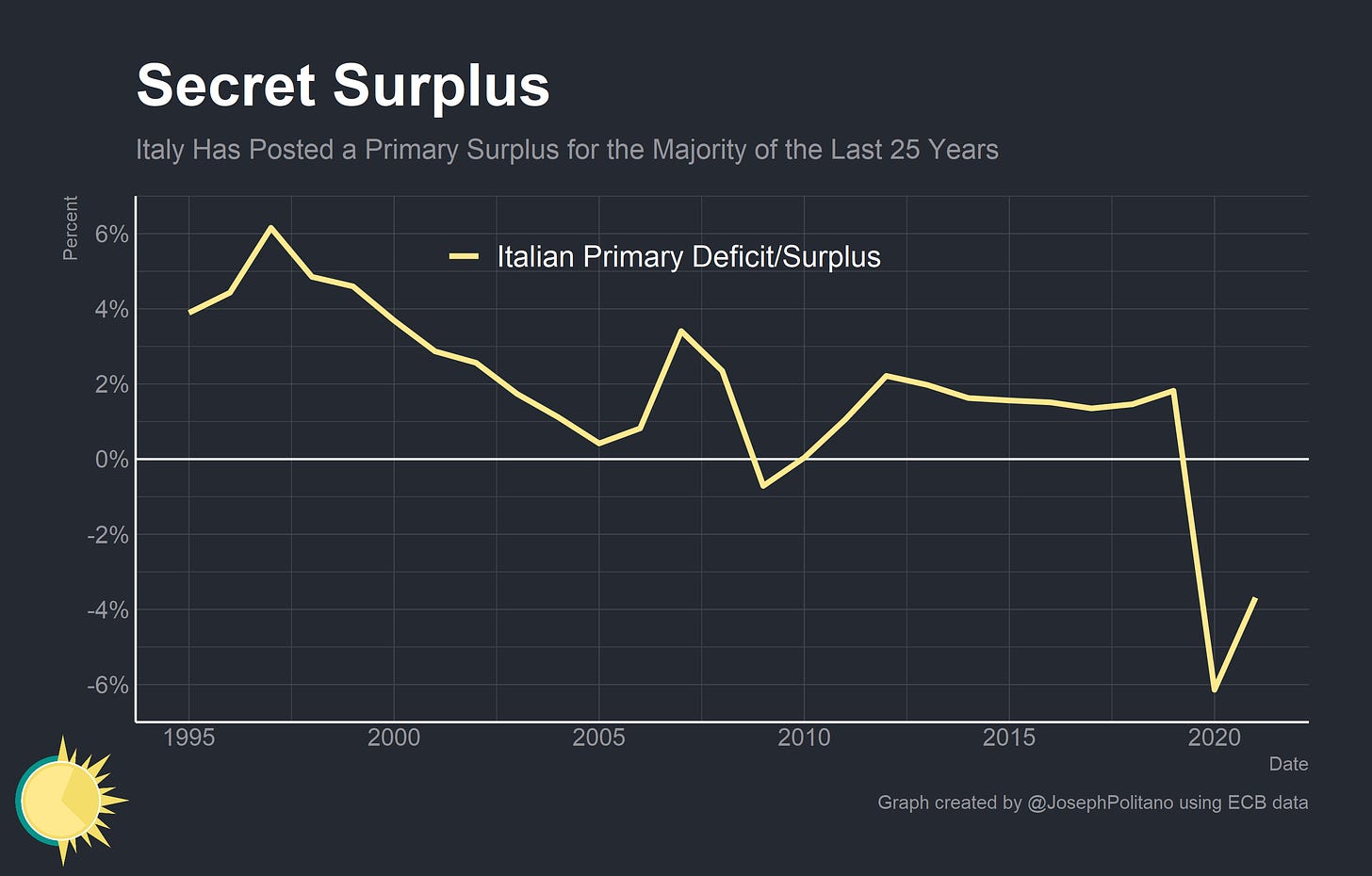

Still, before the Great Recession there was an unspoken assumption that the ECB fully backstopped national government debt. After all, how could the institutions of Europe simply allow an entire country to default unnecessarily? The 2008 financial crisis put the first cracks in that view, but it was the ensuing Euro crisis where faith collapsed. Rapid contractions in real GDP lead to capital and labor outflows, a credit crunch wrecked the financial system, and fragmentation within the Eurozone left unified monetary policy a drag on periphery economies. The stance of monetary policy appropriate for Germany was no longer appropriate for Greece—and the reality of monetary policy remained too tight even for Germany. Italy, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and Greece suffered a mixture of balance of payments crises, credit contractions, and financial freezes that resulted in a string of bail outs and reforms. Interest rate spreads between periphery nations’ bonds and German bonds exploded as it became clear weaker countries might be allowed to collapse—and it wasn’t until ECB President Mario Draghi committed to backstopping the Euro system that spreads contracted again.

“We are not here to close spreads, there are other tools and other actors to deal with these issues”

Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank

Though outright disintegration of the Euro system was avoided, the bloc entered into a decade-long economic slump that devastated some of the worst-affected nations. Spreads contracted but were never brought back to their pre-crisis levels; markets still believed that there was some chance that major countries like Italy and Spain count fall victim to the same sort of crisis that befell Greece. The result was a vicious cycle—monetary policy was too tight for nations like Italy so output, employment, and investment suffered, the country was too hamstrung by bond spreads and EU fiscal rules to use deficit spending to combat the contraction, and the contraction made monetary policy tighter, increased the likelihood of crisis, and boosted bond spreads. The ECB tried to do enough to keep spreads from exploding again—but refused to do enough to close them completely. In 2019 spreads on Italian bonds were higher than during the initial part of the Great Recession.

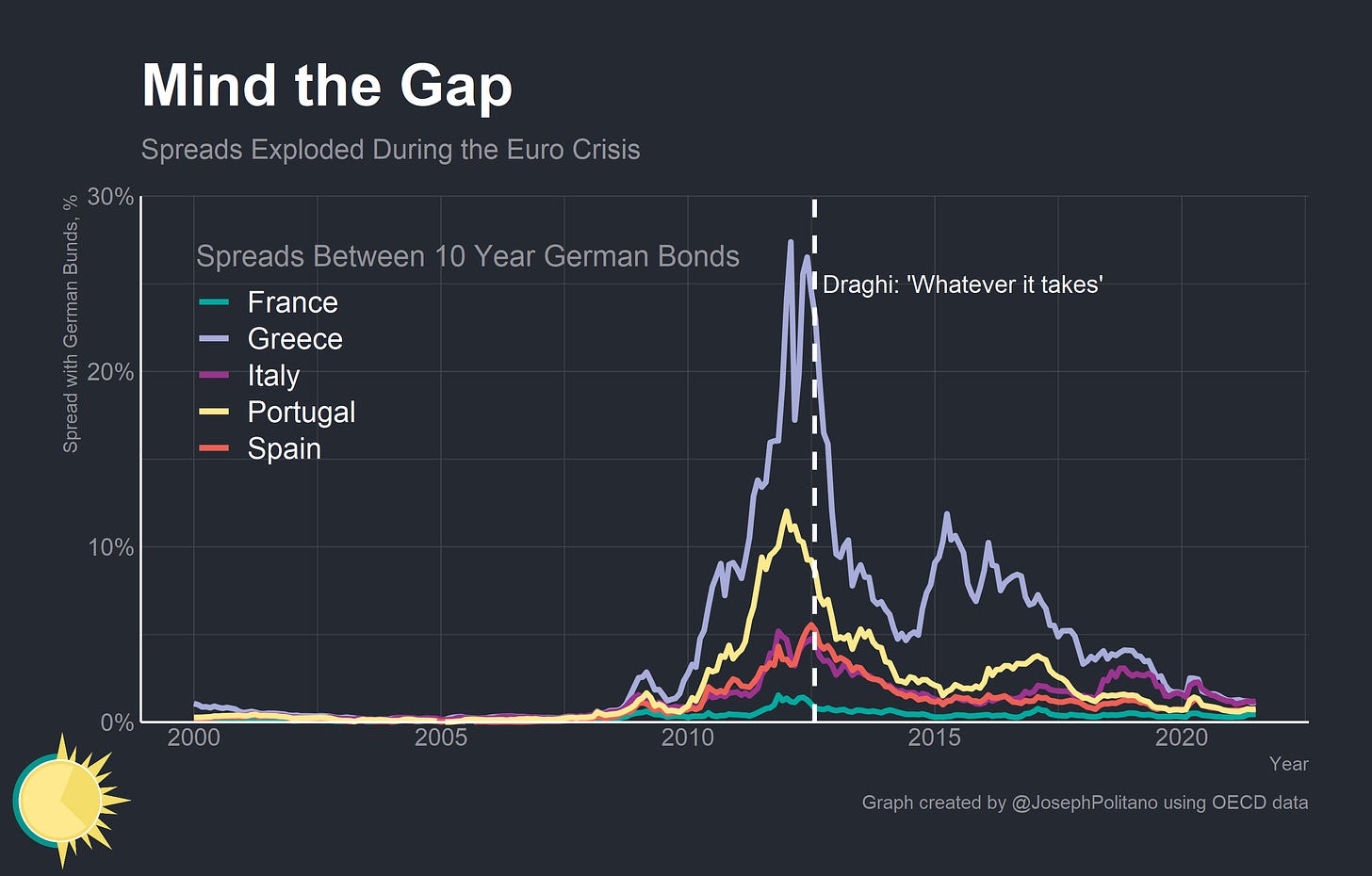

Today, the ECB is raising rates for the first time since 2011 in order to combat inflation. There is a reasonable debate about whether this is necessary—inflation in the Eurozone is concentrated in the continent’s energy crisis and the bloc is in a weaker economic position than nations like the US—but the downstream consequence of this monetary tightening has been an increase in Italian and Greek spreads as financial conditions worsened.

The good news is that the ECB is finally acknowledging the problem—last month the governing council held an emergency meeting to discuss fragmentation risks. This week they officially unveiled the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI), an anti-fragmentation tool designed to keep bond spreads from reaching a level that would prevent the effective transmission of monetary policy. Combined with the issuance of more than €900B in common EU debt through the Next Generation EU and SURE pandemic recovery schemes, this instrument quietly lays critical groundwork for a better, more unified European macroeconomy.

You Know What They Say About Assumptions

At a general level, the problem with the Eurozone is that the bloc only loosely fits the definition of an optimum currency area—the theoretical ideal for an economic bloc that should all share the same currency. Critically, unlike in the US there is no risk-sharing through fiscal transfers between members of the Eurozone. Partially as a result of this, the business cycles of EU member states can become extremely desynced.

As the business cycles become desynced, the same monetary policy can be too tight for one Eurozone country and too loose for another. If the Italian economy demands a lower interest rate then the German economy then tough luck—there is only one set of Eurozone interest rates. Either Germany has to accept a rate that is too low or Italy has to accept one that is too high—and in practice the Italians are forced to accept one that is too high. The result is that Italy has perennial low nominal and real growth—if they had their own currency they could pursue a more stimulus to reach their inflation targets and boost employment, but within the Euro system they can only lobby for more stimulus from the ECB.

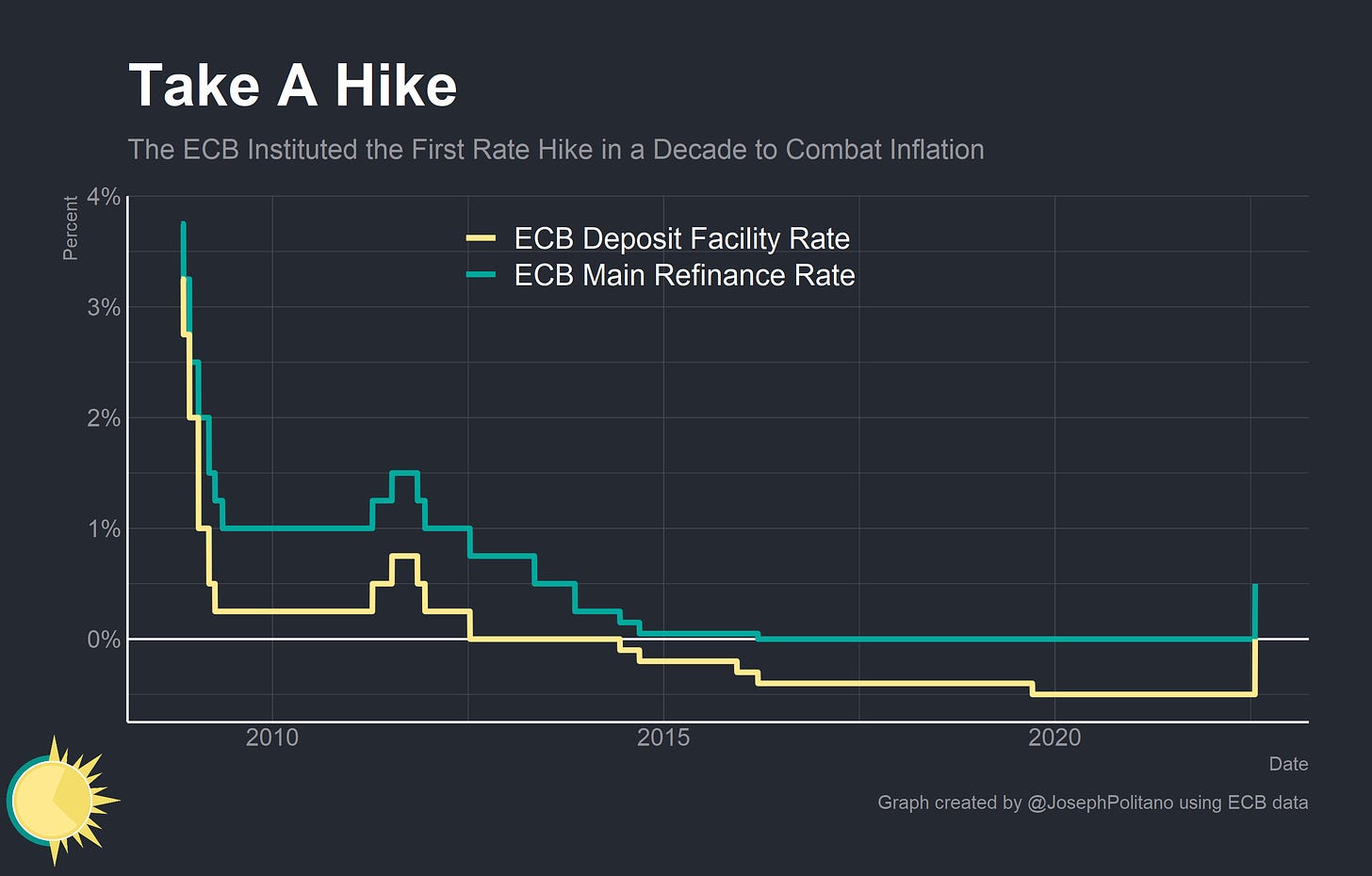

The monetary policy discrepancies would be less of a problem—if not for the fiscal restraints imposed on nations like Italy. Theoretically the Italian government should be able to exploit the fact that ECB policy is fixed across the continent—if they instituted deficit spending to stimulate the economy the ECB would not fully offset it, allowing them to buoy their economy back in line with the the stance of Eurozone monetary policy. In practice the Maastricht Treaty (which sets debt and deficit limits for Eurozone members), the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP, which provides enforcement threats to prevent “unsustainable” fiscal spending), and rising bond spreads prevent the Italian government from pursuing unilateral stimulus. In fact, Italy has run a primary surplus (a government budget surplus before interest expenses) for the better part of 25 years. Unable to devalue their currency or implement fiscal stimulus, the Italian economy is forced to wallow in stagnation—GDP per capita in Italy remains below its 2007 peak and sits at 1/2 of what it is in the United States.

“The TPI will be an addition to our toolkit and can be activated to counter unwarranted, disorderly market dynamics that pose a serious threat to the transmission of monetary policy across the euro area. By safeguarding the transmission mechanism, the TPI will allow the Governing Council to more effectively deliver on its price stability mandate.”

This is where the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) comes in—even the name is a tacit admission that sovereign bond spreads make effective monetary policy transmission difficult! The TPI gives broad authority to the ECB to make purchases of sovereign bonds at its discretion in order to prevent “a deterioration in financing conditions not warranted by country-specific fundamentals”. The entire purpose of the mechanism is effectively to control spreads and partially backstop the borrowing of countries like Italy and Greece.

There are two other key features of the TPI worth highlighting. First, the instrument seems to fully sidestep the capital key that the ECB’s usual bond-buying programs are supposed to abide by. The capital key basically says that the ECB should purchase bonds from all member nations in proportion to their size within the bloc’s economy—and since the TPI implicitly targets only distressed debt securities it cannot be compatible with the capital key. That’s a big deal considering how much the capital key constrained the ECB during the latter part of the 2010s and during the pandemic—the central bank had essentially purchased all available outstanding German debt and was left without enough wiggle room to support nations like Italy. If the TPI survives legal challenges, it will essentially allow the ECB to direct support on a country-by-country basis.

“Purchases under the TPI would be conducted such that they cause no persistent impact on the overall Eurosystem balance sheet and hence on the monetary policy stance.”

The second key feature is that the bond purchases under the TPI are supposed to be neutralized on the ECB’s balance sheet. In other words, for every Euro of Italian or Greek bonds bought by the ECB under the TPI another Euro’s worth of other bonds will be sold to offset. Theoretically, this allows the ECB to transmute risky Italian debt into safe German debt by buying Italian bonds and selling German bonds. Even better, the ECB could transmute Italian debt into EU debt by selling some of the common EU debt from the Next Generation EU and SURE programs that the ECB bought during the pandemic.

In other words, the TPI could represent a soft version of the debt assumption that Hamilton accomplished in the US. Instead of the EU directly absorbing the totality of sovereign debt throughout the continent, the ECB could transmute debt burdens between sovereign nations and the EU in order to close spreads and make all members’ sovereign debt roughly equivalent1. Doing so would open up the door for allowing nations like Italy to run persistent primary deficits, increasing nominal and real growth while bringing the Eurozone closer to an optimum currency area. This sounds radical, but in fact it would effectively only meaning returning the Eurozone to pre-Great Recession norms while relaxing some of the fiscal spending rules.

Give me a Bazooka and I Won’t Have to Use It

“We would rather not use TPI, the Governing Council would rather not use it—but if we have to use it we will not hesitate, we will not hesitate.”

Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank

That is, however, the oversimplified and optimistic take. In practice the ECB does not need to even use the TPI—it just needs to convince markets that it is serious about closing spreads and has the firepower to back up that commitment. On that mark the ECB seems to be faltering—spreads contracted since the announcement of an anti-fragmentation tool but remain higher than at any point since the initial spike at the beginning of the pandemic. Markets seem to interpret the ECB’s goals as closer to “we will intervene in the event of an acute crisis in the sovereign bond market” than “we want to actively and preventatively close bond spreads.”

Though the ECB has granted itself a significant amount of discretion in deploying TPI, its statements make it clear that the central bank does not want to supersede the EU’s preexisting fiscal rules and that it remains concerned about the long-term sustainability of public debts in many countries. Recipients must not be subject to an Excessive Deficit Procedure, lack macroeconomic imbalances, maintain “fiscal sustainability”, and keep “sound and sustainable macroeconomic policies”—in other words, this is no blank check.

Political constraints also play a critical role here—Greece and Italy are not exactly known for their political stability, and the resignation of former ECB President Mario Draghi from his role as Italian Prime Minister poetically occurred just as this anti-fragmentation tool was being rolled out. Antagonistic, incompetent, or disorganized leadership within target states will make the TPI much less effective and make the ECB’s job that much harder. The ongoing pandemic and Russian invasion of Ukraine have presented large enough crises to induce a more unified front amongst EU members, but it remains plausible that old disagreements will resurface if the crises abate—a future German government may not be as cooperative as today’s more liberal coalition.

Still, nothing is as permanent as a temporary ECB program. Monetary and fiscal policy tools in the Eurozone have a tendency to be enacted in times of crisis and generally grow into full-fledged programs through bureaucratic creep. There’s a plausible future where the TPI grows into a standing system for regulating or preventing bond spreads—and this system thereby leads to stronger, more coordinated macroeconomic policy within the Eurozone.

Conclusions

Europe is in a moment of crisis right now—between rapid inflation, an acute energy shortage, political fragmentation, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, there is no shortage of threats on the continent. If the chance of a recession is elevated in the US it is even higher in the EU, and the recovery in the EU has arguably been weaker than in the US. The long-run structural deficiencies of Eurozone economies have never been more apparent—and it has never been more necessary for European authorities to defuse the risk of another self-imposed sovereign debt crisis.

However, it’s worth remembering that it took more than a century for America to solidify the kind of credit and borrowing that made the country such a financial and economic powerhouse. And it also took crisis upon crisis before American modernized, centralized, and institutionalized its credit markets2. By that mark the ECB is moving remarkably fast—though still too slow for its citizens’ sake and by modern economic development standards.

Still, the TPI is a decent launching point for a stronger, more unified Eurozone. The Hamiltonian bargain seems to have involved giving hawkish parties the 50 basis points hike they desired while giving dovish parties the anti-fragmentation tool they desired—an exceptional deal for the doves if TPI is effective and is able to stick around in the long run. Who knows, someday they may even make a musical about Christine Lagarde.

I hesitate to describe TPI in such literal, transactional terms but I feel it is necessary in order to drive home the point about how the TPI can backstop sovereign debt obligations. In truth the only thing that is needed to backstop sovereign debt a combination of enough firepower and credible commitments from the ECB that they want every nations debt treated as approximately equal.

A large part of the inspiration for this post came from Jeffry Frieden’s 2016 essay comparing developments in the early US to the early Eurozone. I do not 100% subscribe to the essay’s interpretation of events but I still think it’s worth a read if you’re interested.

Great article, but from a German perspective this transfer of credit is highly unpopular and considered unconstitutional by the German Federal Constitutional Court; one of the main reasons why it upheld the PSPP in 2020 was the capital key to prevent an open financing of member states by the ECB, which is prohibited under the EU Treaties.

I find it amusing that anybody thought the tpI would be anything other a dressed up way for the ECB to buy BTP's and sell Bunds to close the spread. In fact, the whole point of the sterilization is to have a mechanism to sell Bunds.

I am not so optimistic that the Europeans will reach any true agreement to either federalize or mutualize their sovereign debt until such time as the euro is on the cusp of disintegration. I fear the bigger problem is that it won't be the weaker countries that will be looking to leave, but the Germans as they will get tired of funding the rest of the continent. this will be especially true if Russian natural gas stops flowing and Germany falls into a deep recession.

the euro has a very steep wall of worry to climb in my view, at least until the Fed blinks and all the hawkishness leaves there. At that point, the only certainty seems that market volatility across asset classes will rise dramatically.

thanks for your analysis, which is always clear and on point