The EU's Industrial Crunch

How European Industry is Dealing With High Energy Prices—and Who is Picking Up the Slack

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 19,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

The European Union is in the midst of an acute energy shortage in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Vladimir Putin’s efforts to cut off significant parts of Europe from critical natural gas supplies have inflicted more damage on European economies that were already struggling amidst the pandemic. Natural gas is not only essential for home heating, cooking, and electricity—it also represents critical energy supplies for European industry and a direct input into many manufacturing processes.

European countries have reasonably decided that households and consumers should have priority over industry for limited natural gas supplies—Britain’s NHS Confederation Chief warned of thousands of deaths due to insufficient heating this winter unless swift action was taken—and they have made a concerted effort to stock up on gas for this winter and source supplies from outside Russia. Right now, EU gas storage facilities are 95% full and the bloc gets more natural gas from the United States than from Russia.

Still, important questions remain for European industry. Accepting that it will take time for domestic energy production to ramp up and for more global natural gas export capacity to be built out, there are essentially three broad ways European industry can respond to the energy crisis—increasing energy efficiency to do more with less, importing more manufactured goods from abroad, or accepting lower real output.

The good news is that European manufacturing is definitely doing more with less—EU-27 manufacturing production notched new record highs in both August and September. German manufacturing—which had strong connections to Russian gas through the now-shut-down Nord Stream pipeline—continues to lag, as does Italian manufacturing. But with German industrial gas consumption down 20%, the comparatively slight decline in industrial output proves some companies are getting more energy efficient—a survey from the IFO institute showed 75% of German manufacturing firms have saved natural gas without production cuts.

Still, aggregate strength belies significant weakness in key sectors. Energy may be a basic input into essentially all modern manufacturing processes, but the energy intensity of different industries varies wildly. Industries that rely more on energy or natural gas—like metals and chemicals—have suffered larger hits to output amidst the energy crisis. The German statistical agency developed a special index of energy-intensive manufacturing industries (namely metal production & processing, glassware & ceramics manufacturing, paper & cardboard manufacturing, and coking plant & petroleum processing) and showed that energy-intensive production is down 10% this year while overall production remained flat. Those industries consumed 76% of German industrial energy in 2020—hence why these sectors are seeing drops in output and why large reductions in energy consumption can come with hits to only a few manufacturing sectors.

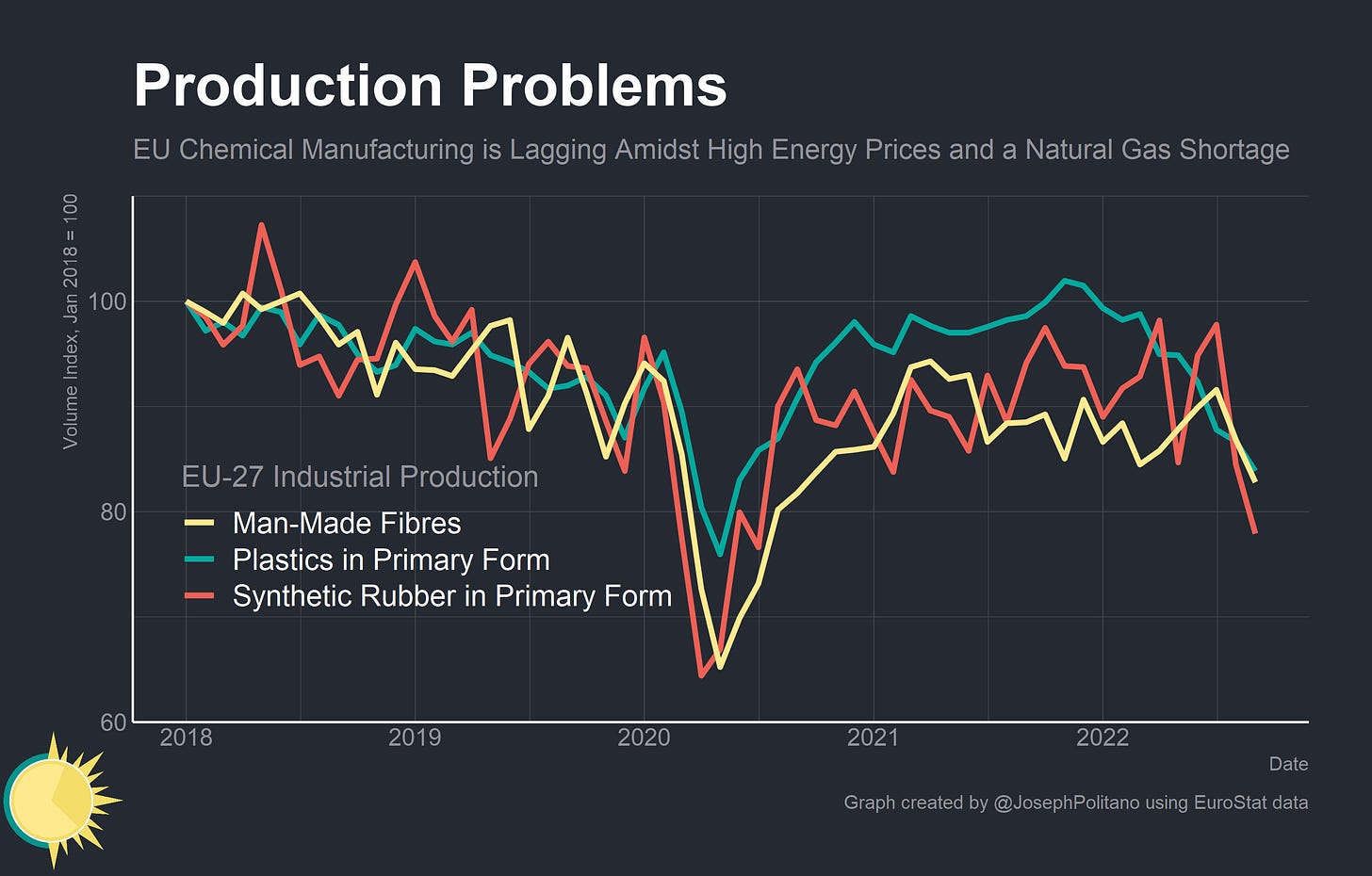

Within the chemical sector plastic, synthetic rubber, and man-made fibre output are taking some of the biggest hits, all of which have seen 15-20% declines compared to 2018. Data on nitrogenous fertilizer production—a key agricultural input hit especially hard by the loss of natural gas supplies—is only available for the Euro area, but still shows a 10% decline.

Within the metal production and processing sectors, it is copper, iron, steel, and metal castings that have seen the biggest production declines. European iron, steel, and ferroalloy output is down nearly 20% from 2018 levels and copper output is down 10%.

So European manufacturing has thus far remained resilient in the face of the continent’s energy shortage, although several key energy-intensive sectors are suffering dramatically. However, it is worth placing output declines in the context of global goods shortages and comparing them to the no-energy-crisis counterfactual—European manufacturing output is stagnant at a time of massive global goods shortages and elevated prices. Capacity idled due to the energy shortage is capacity that cannot meet the yawning gap between global supply and demand.

Still, it is clear that European producers are thus far doing more with less—increasing the energy efficiency of their operations and keeping output relatively stable during the crisis. But in the sectors with output declines are Europeans importing more from abroad, or are they just living with less?

The answer seems to be a bit of both—imports of key goods have increased significantly, particularly from the US and China. Meanwhile, the EU’s pandemic recovery and real output growth have stalled out thanks to the energy crisis. How quickly European growth recovers and how long the EU remains reliant on external imports will have critical implications for the global economic outlook.