The Fault in R-Stars: The Problems in Policymaking Based on "Natural" Rates

Policymakers Have Put Far Too Much Faith in Unobservable "Natural" Rate Estimates, and the Results Have Been Catastrophic

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

To this day, I cannot read without irritation (even outrage) that oft-repeated, canonized expression the natural rate of unemployment. Natural? Did the green Nature of forests and hares, rocks and earthquakes decree at the same time that there should be unemployment?

János Kornai, Dynamism, Rivalry, and the Surplus Economy

In 1898 Swedish economist Knut Wicksell published his masterwork Interest and Prices in which he canonized the idea of the “natural rate of interest” (represented by R*). In his estimation, if interest rates go above the “natural” rate, output will decrease and prices will decline and vice versa if interest rates go below the “natural” rate. This structure was adopted throughout macroeconomics and remains part of the core teachings of the field. Over time, other stars were added to this constellation: the natural rate of unemployment (u*) and potential gross domestic product (Y*).

Throughout congress, the federal government, and the Federal Reserve, the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU) was canonized into policymaking. Based on the presupposed tradeoff between inflation and unemployment expressed through the Phillips Curve, NAIRU determines the lowest unemployment rate possible without pushing inflation above target. As the story goes, when unemployment is at NAIRU real GDP will be equal to potential GDP and inflation will be on target. Various statistical agencies, modelers, researchers, and planners sought to unearth these “natural” values to guide policy in their direction and maintain macroeconomic stability.

These estimates, however, are intensely problematic. They prescribe precise values to unobservable, unknowable variables and can lock policy in amber regardless of fundamental changes in the economy. Estimates are revised dramatically as prior ones are disproved by real-world data, and even after re-estimation their predictive power remains low. “Natural” rates are stacked on top of each other, with one natural rate relationship determining the others in a way that further removes policymaking from empiricism. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) and other policymakers have recently leaned away from their own natural rate estimates after wrestling with their flaws. It would be prudent for the Federal Reserve and other policymaking institutions to be agnostic about the “natural” rates and instead focus more on data-driven policymaking while navigating with an acknowledgement of what it cannot know.

The Natural Rate of Unemployment

At the first floor of the natural rate system is the natural rate of unemployment, usually expressed through the NAIRU. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) builds its estimate of the NAIRU for its potential GDP estimates, which in turn feed into their policy and macroeconomic evaluations. Essentially, the gap between the CBO’s estimate of NAIRU and the realized unemployment rate should induce above-target or below-target inflation. This is the traditional Phillips curve relationship, where too-low unemployment causes higher inflation and too-high unemployment causes lower inflation. Interest rates will have to shift in order to bring unemployment back to NAIRU in order to stabilize inflation.

There’s several problems with this system; for one, the Phillips curve relationship between unemployment and inflation does not hold to any semi-rigorous empirical degree. Unemployment is a terrible measure of labor market slack, its historical relationship with inflation is weak, models have to be calibrated with inflation expectations (another unobservable) to work, and there is no reason to expect any historical relationship to remain stable ad infinitum. Phillips curves have been “flat” in recent history, meaning that the relationship between unemployment and inflation has nearly completely broken down. As a result, the gap between the CBO’s long-run noncyclical unemployment estimate and the real unemployment rate has extremely little predictive power over inflation. This is despite the non-cyclical unemployment estimate being revised in 2021, essentially allowing CBO to develop a model estimate that works as well as possible given prior data.

The CBO’s NAIRU estimates, which are separate from their estimates of non-cyclical unemployment, also fluctuate dramatically based on changing data. Now, it should be said that it is good that the CBO attempts to correct their estimates on the basis of new data, but it should raise questions about the significance of NAIRU estimates if they shift so dramatically in such a short period of time. In particular, the CBO revised up their estimates of NAIRU in the immediate aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis and then revised down their estimates after the 2018 experience proved that their prior estimates were too high. Their current NAIRU estimate would put current unemployment within 1% of its stable minimum despite millions of job losses as a result of the pandemic. It should also be noted that the CBO presumes unemployment rates by demographic group were at their “natural” rates in 2005, essentially institutionalizing massive racial and gender employment gaps into policymaking.

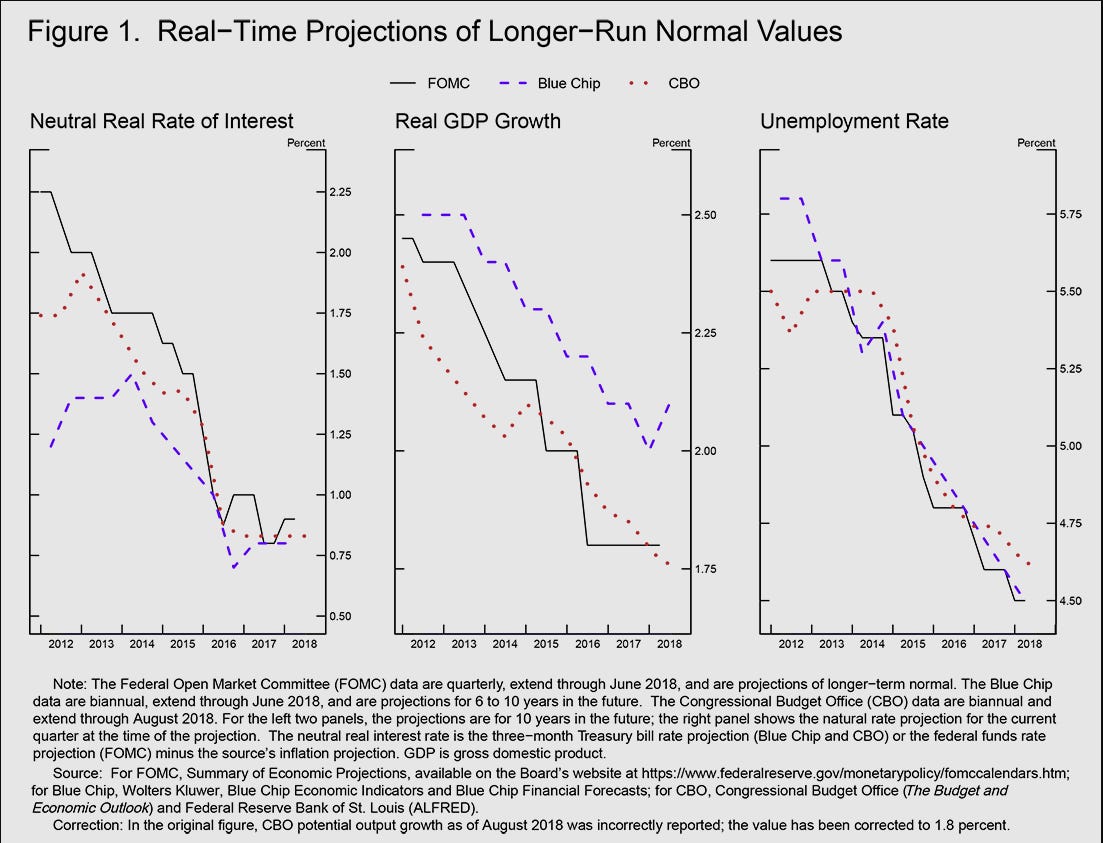

Even the Federal Reserve is not exempt from NAIRU misuse and misestimation. Since the recovery, both the FOMC and the Federal Reserve staff’s estimate of the sustainable long run unemployment rate were excessively high. In 2016, the unemployment rate sank below both estimates and did not spur excessive inflation, leading the FOMC estimates of longer run unemployment to sink significantly. Even in the pre-pandemic labor market the midpoint of FOMC estimates indicated that unemployment should be increased to counteract inflation. This is despite real slack in the labor market being significantly high.

Regardless of the quality of NAIRU estimates, there is no reason to base a “natural” estimate on unemployment at all. For one, unemployment is an extremely fickle data point that does not represent capacity constraints in the labor market. In 2016, when unemployment hit the Federal Reserve’s NAIRU estimate, headline PCE inflation was 0.82% and trimmed mean PCE inflation was 1.63%. The prime age employment-population ratio was lower than any pre-crisis period in recent memory, meaning fewer working age Americans were at a job. This is because headline unemployment metrics do not count discouraged workers, the people who are not working and have fully given up searching for a job. Unemployment metrics only count those who are actively looking for work and are unable to find it. Additionally, it does not consider wage and compensation growth at all. It's also a lagging indicator, as significant economic slowdown usually needs to occur before measurable unemployment manifests.

Despite this, the NAIRU pervades the thinking of macroeconomists, as evidenced by former Treasury Secretary Larry Summer’s evaluation of the current US economy:

Third, the data flow as I read it corroborates my concerns. Job opening and quit rates suggest record levels of labor tightness, as do surveys of employers about hiring. Unemployment and employment measures suggest some slack relative to pre pandemic NAIRU estimates but these are imprecise and record levels of structural change are likely to raise NAIRU estimates. We know wage acceleration is very sticky but it is coming.

Larry Summers, in an interview with Noah Smith

Breaking from this thinking requires macroeconomists to wrestle with the constantly shifting nature of the economy and evaluate a broad suite of labor market slack indicators instead of statically looking at unemployment metrics. Policymakers that instead take the idea of NAIRU seriously divine the other “natural” rates through some derivation of NAIRU. This makes the NAIRU-derived “natural” rates and their policy recommendations even less useful than NAIRU itself.

The Natural Rate of Interest

At the Federal Reserve, the gap between unemployment and the NAIRU is inserted into the econometric models that staff use to develop policy recommendations to FOMC members. The basic logic is that a higher unemployment rate above NAIRU indicates that the real interest rate should be lower to combat unemployment and that a lower unemployment rate below NAIRU indicates that the real interest rate should be higher to combat inflation. The first problems in this approach should be obvious by now; the unemployment-inflation relationship is incredibly weak, unemployment is a bad measure of labor market capacity utilization, and NAIRU estimates are often wrong. Nevertheless, the Federal Reserve’s staff models lend a ton of credence to estimates of NAIRU in developing interest rate recommendations.

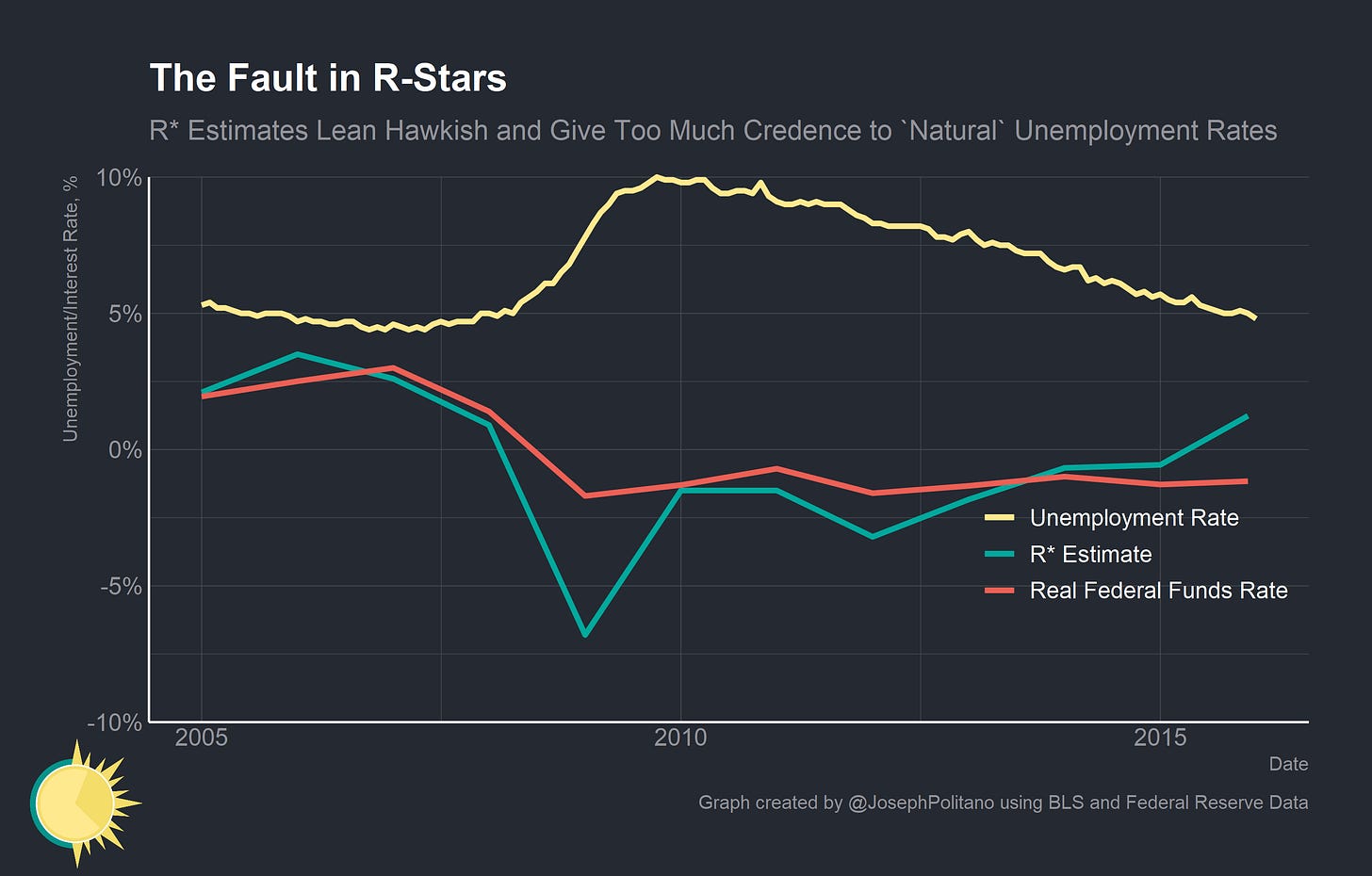

Take, for example, “natural” rate estimates from 2015. In the January 2015 “tealbook” the Federal Reserve staff estimated that the “natural” real interest rate (R*) was -0.56%. As soon as the unemployment rate crossed below the staff’s NAIRU estimate of 5.1% in the December 2015 “tealbook”, the estimated “natural” real interest rate jumped all the way to 1.24%. These estimates formed part of the reason that many FOMC members were okay with tapering Quantitative Easing (QE) by 2014, and the result was a measured slowdown in growth and mini-recession in manufacturing.

Critically, the gap between the R* estimate and the actual real federal funds rate also has extremely limited predictive power over forecasted inflation. Aside from in 2008, when the real federal funds rate was far above staff’s R* estimates and deflation occurred thanks to the financial crisis, inflation has remained almost totally uncorrelated from the gap. Critically, the early 2007 R* estimates were far too high in retrospect, and R* estimates from 2014/2015 suggested oncoming excess inflation that never materialized. It took until after significant additional employment growth was made by 2018/2019 for trimmed mean PCE inflation to remain at 2%, and even then the Federal Reserve was forced to unwind several rate hikes before the pandemic hit. FOMC members are paying less attention to R* estimates as a result, which has been a massive improvement for US monetary policymaking.

The Natural Rate of GDP Growth

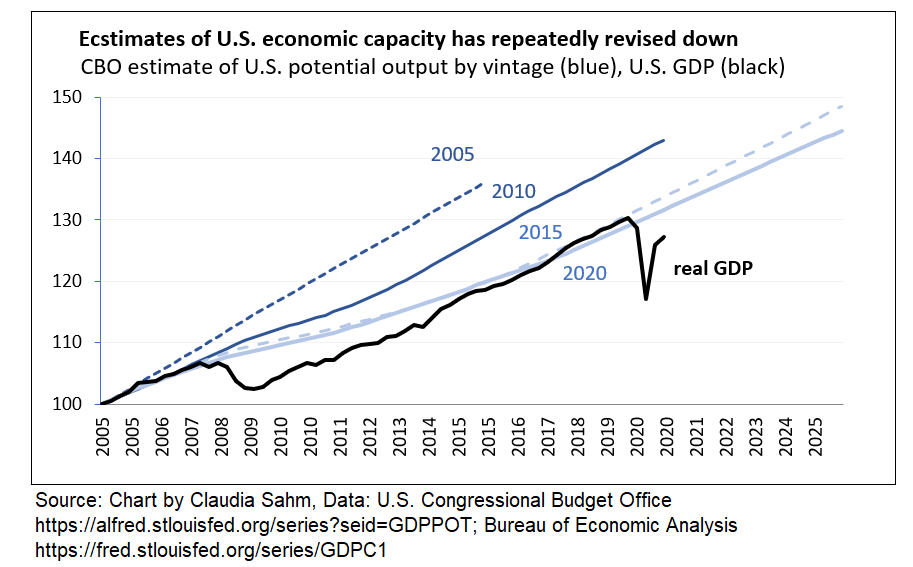

The final stop on the CBO and Federal Reserve’s econometric modeling is potential GDP—the maximum stable level of real growth that the economy can achieve. Estimates usually line up with extrapolation from prior trends, as real GDP per capita in the US had grown pretty stably around 2.2% a year for decades. The crucial flaw in recent potential GDP estimates is that they have been revised down dramatically in the wake of the financial crisis, essentially locking policymakers into the belief that lost growth could not be regained.

Take the CBO’s estimates. They have been revised down significantly since 2005, reflecting the organization’s lack of confidence in the US economy rebounding from the great recession. Critically, when US GDP went above “potential” during 2018 and 2019 there were no adverse consequences; as said before inflation was muted and the Federal Reserve was forced to retreat from some of their rate hikes. No wonder, because these estimates truly did not reflect anything close to an upper level for economic growth.

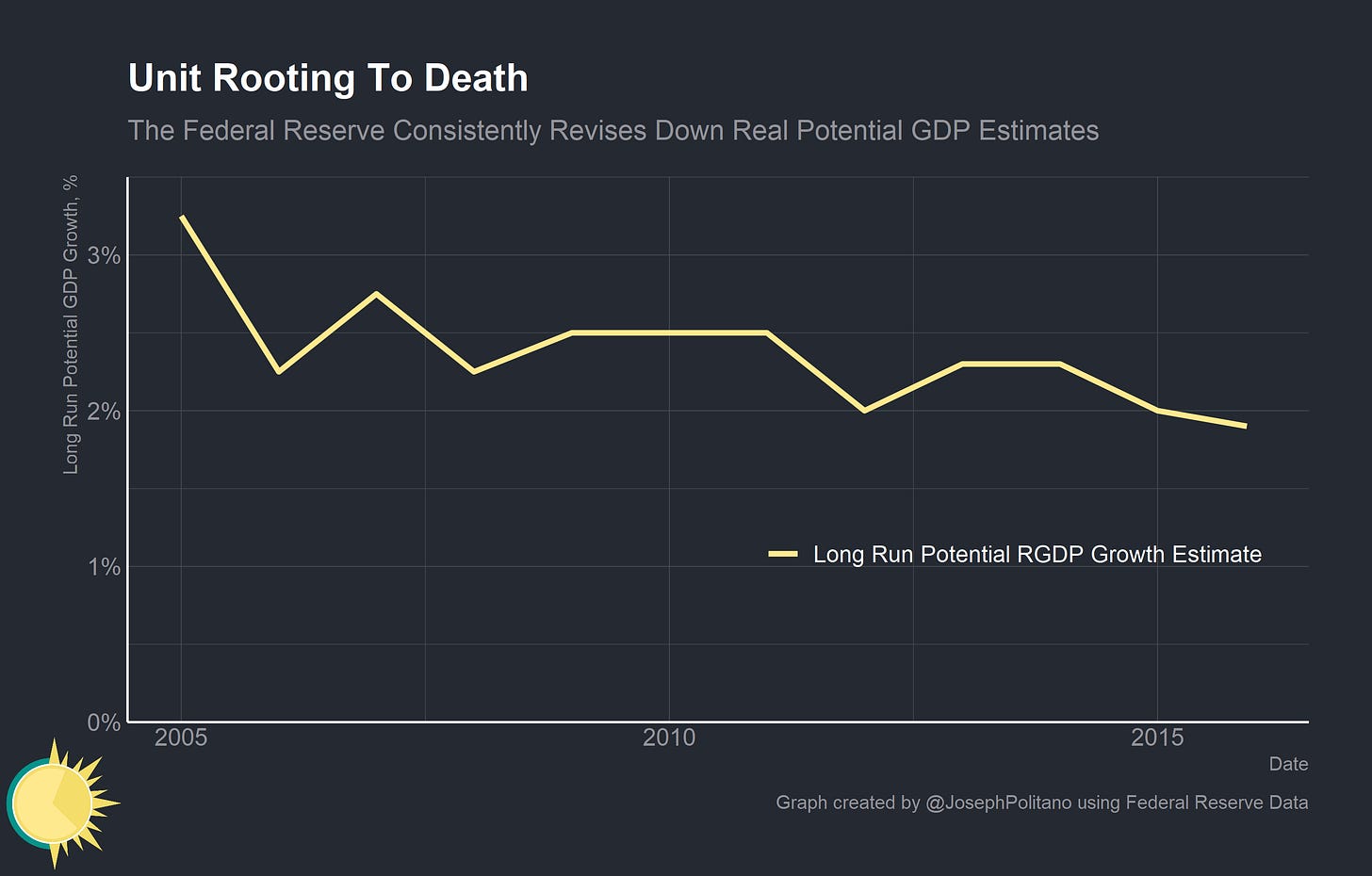

The Federal Reserve’s long run potential real GDP growth estimates reflect much of the same problem. Since 2005 estimates have been revised downward repeatedly as the weakness from the 2008 economy was believed to be a standard state of affairs. What good is a measure of “potential” growth if anytime the economy performs poorly “potential” is simply revised downward? That is the failure of these “natural” estimates in the last decade; they increasingly presumed that the poor economic performance was evidence that “natural” growth was decreasing and “natural” employment was decreasing. Instead of being used to illustrate the wide gap between the quality of the pre-recession and post-recession economies, they were used to etch the failing economy in stone and argue against the possibility of improvement. When policymakers decided to set interest rates or score fiscal spending based on these estimates, they were implicitly evaluating the US economy as unable to improve. When they acted on these estimates, they wrote their “natural” limits into the economy itself in a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy. Of course unemployment won’t go below 5% if every time it does policymakers work to limit further economic growth out of misplaced fears of inflation.

The trend of recent “natural” rate estimates is clear: lower interest rates, lower GDP growth, and lower unemployment estimates. It is worth noting the somewhat contradictory nature of these changes—although policymakers and professionals clearly believe that unemployment can go lower and interest rates will remain low, they are increasingly bearish on the future economic growth of the United States. This is partly a direct result of prior misestimation, as overly tight monetary policy from the financial crisis has tampered future GDP level and growth expectations. However, it also reflects the last vestiges of the prior “natural” estimation system working their way into current policy. If we can push employment up and institute better monetary and fiscal policy, there is no reason to believe we cannot return to the pre-crisis 2.2% real GDP per capita growth rate.

Conclusions

I see the current path of gradually raising interest rates as the FOMC's approach to taking seriously both of these risks. While the unemployment rate is below the Committee's estimate of the longer-run natural rate, estimates of this rate are quite uncertain. The same is true of estimates of the neutral interest rate. We therefore refer to many indicators when judging the degree of slack in the economy or the degree of accommodation in the current policy stance. We are also aware that, over time, inflation has become much less responsive to changes in resource utilization.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, August 14th, 2018

The Federal Reserve in particular has made significant progress in reworking the “natural” rate framework under Jerome Powell, leading to increased reliance on market indicators and decreased faith in estimates like NAIRU. When the rate hikes of 2018 proved to be too much for the US economy, the FOMC was comfortable backing off and easing policy despite low unemployment rates.

Under a better policy regime, however, the hikes would not have happened in the first place. It was clear in retrospect that the economy remained far away from full employment and the threat of persistent above-trend inflation was limited. Even if policymakers were taking NAIRU estimates less seriously, they were still trusting them far too much.

The “natural” rates may be good in explaining monetary economics to students or modeling hypothetical economies, but policymaking from unobservables is a recipe for disaster in the real world. It is imprudent to put that much stock into one variable, especially a terrible measure like unemployment, as the real economy is an incredibly complex system. Expecting the relationship between any macroeconomic variables to remain constant over time violates the Lucas critique, yet remains part of policymaking throughout the world. The credence given to these estimates flies in the face of the understanding and deferment to dispersed knowledge throughout most of modern economics.

It would be wise for policymakers, especially central banks, to acknowledge that they are always choosing a subset of policy paths rather than reaffirming the fundamental Nature of the world. In that respect, they should be agnostic to the “natural” rates and always lean on the side of supporting income and output over fighting inflation on the margins. This is why choosing an output target, like gross labor income, is a much better framework than trying to overoptimize intermediate variables like unemployment and interest rates. Policymakers will always need some rigorous econometric analysis to inform their work, but until they stop looking to the stars for guidance they will remain at risk of getting lost.

If you like what I do, consider subscribing to get free economics news and analysis delivered to your inbox every Saturday!

I did something along those lines a few years ago. "Star trekking" is really a waste of time, effort and resources! https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2015/10/25/looking-for-wally-when-there-are-many-wallies/