The Fed Sees a Softer, Higher Landing

Fed Forecasts Now Imply a Recession is Not Necessary to Stop Inflation and that Rates Might Remain Higher For Much Longer

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 35,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

The FOMC decided to keep interest rates steady yesterday, sounding more optimistic about the American economy than at any point over the last year. Critically, the new projections from meeting participants essentially erased the recessionary fall in growth and rise in unemployment they previously implied was necessary to contain inflation. “We are in a position to proceed carefully” was thus the theme of the meeting—Jerome Powell used variations of that phrase 6 times during his press conference, explaining that with inflation cooling and growth holding up, he felt as though the Fed had been afforded the luxury of patience. Risks, so heavily weighted towards excess inflation over the last year, were now perceived as more closely balanced between the Fed’s dual mandate of price stability and full employment.

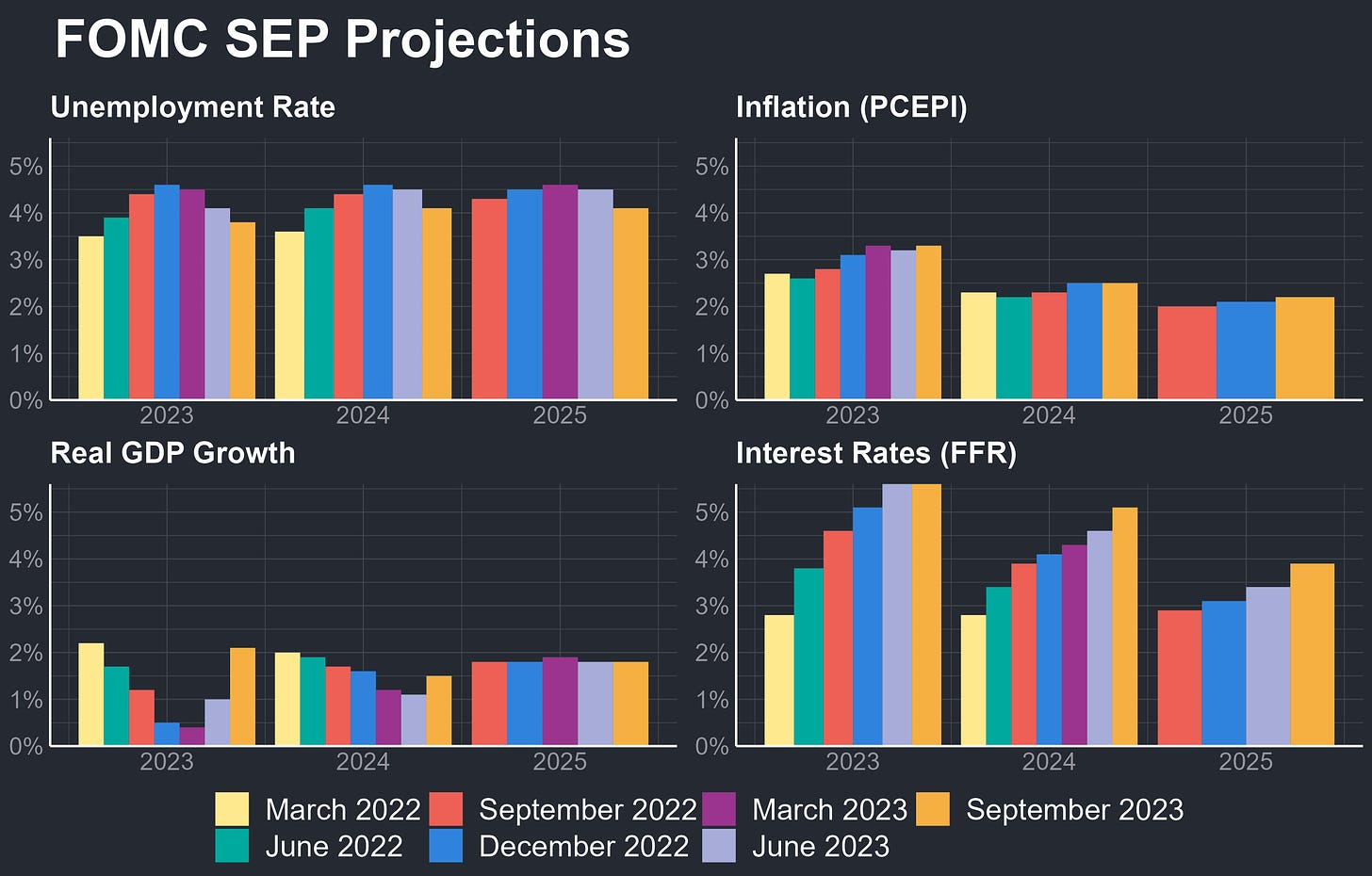

Indeed, compared to June the FOMC has raised their economic projections broadly—they now see higher GDP growth (in excess of 2% this year and at 1.5% next year) and for the unemployment rate to hold steady this year and only experience a “minor” (0.3%) increase next year. They projected slightly higher overall inflation, but this was mostly due to rising energy and food costs—median core inflation projections for 2023 fell 0.2%. Importantly, they continued upgrading their interest rate forecasts—by the end of 2024, the median FOMC member sees rates declining only slightly to 5.1%. Thus, they see a softer landing that requires interest rates to stay higher for longer.

Importantly, FOMC participants are also feeling less uncertain about their macroeconomic forecasts, especially compared to the historically high levels of uncertainty they’ve experienced throughout much of the pandemic. For inflation, GDP, and unemployment, relative uncertainty levels fell to the lowest levels since pre-COVID—though they still remain elevated by historical standards. So not only are the Fed’s projections increasingly consistent with a soft landing, but they feel less worried about the risks to that soft landing.

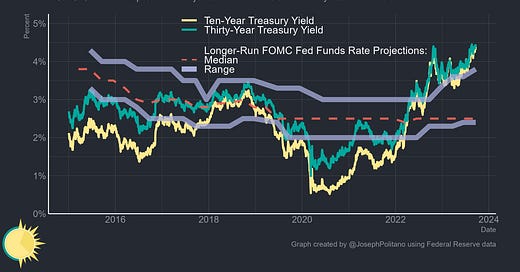

That lower-uncertainty forecast of a softer landing is seen in markets too, where fewer rate cuts are expected next year even as peak expected interest rates for this year have held flat. In other words, markets expect interest rates to stay at high levels for a longer time as the rate cuts that would be expected in a downturn get priced out of expectations. But just how long will rates have to stay high?

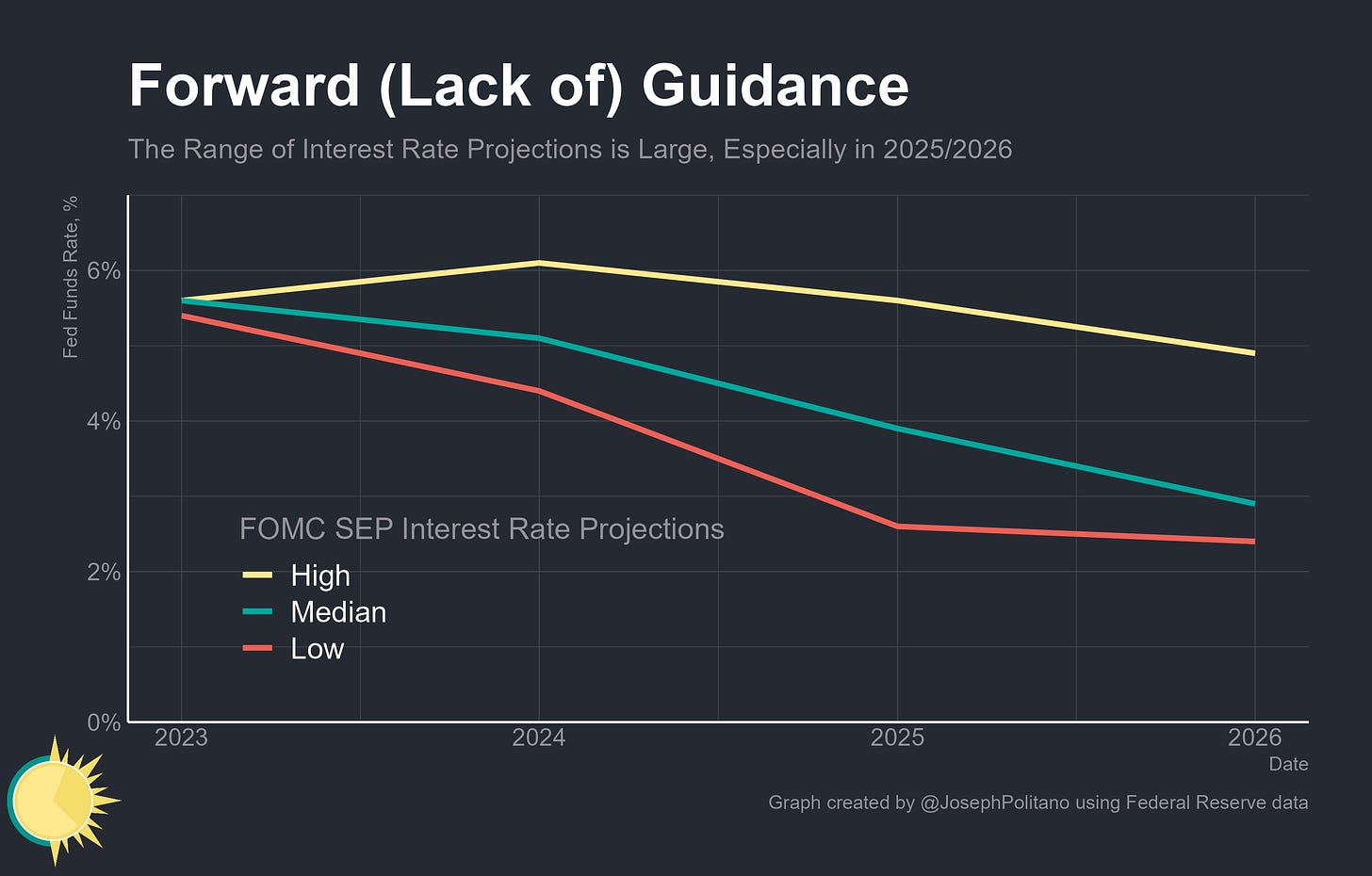

There are large disagreements within the FOMC over that exact question—with different participants seeing radically different appropriate forward paths for interest rates. While most participants see rates gradually declining from here on out, some see hikes continuing into 2024 and driving short-term interest rates to a peak above 6% before declining. The median participant sees interest rates declining to 2.9% by 2026—but for some participants that number is as low as 2.4% or as high as 4.9%. Perhaps most importantly, there are hints within the FOMC projections that a growing contingent at the Fed does not believe high interest rates are just a cyclical blip and are becoming convinced they must permanently stay higher than previously expected.

The FOMC Tries to Find the “Neutral” Rate

In terms of what the neutral rate can be, you know, we know it by its works. We only know it by its works, really.

Jerome Powell, FOMC Press Conference, September 20, 2023

The Federal Reserve still operates within a framework based on “natural” interest rates—where there is one rate path that keeps the economy in equilibrium and raising rates above that path constricts growth, raises unemployment, and dampens inflation while pushing rates below that path does the precise opposite. These frameworks, by virtue of the “neutral” rate’s direct unobservability, come with more than their fair share of problems, and Jerome Powell has come perhaps the closest of any modern Fed chair to acknowledging the flaws in the approach. He has thus often stated that the FOMC is trying to find the natural rate through reactions to its monetary policy, rather than making monetary policy based on divinations of the natural rate.

Still, part of the FOMC projections do ask participants to dictate what the appropriate “long-run” rate of interest will be—that is, the number to which interest rates “would be expected to converge under appropriate monetary policy and in the absence of further shocks to the economy” or in a rough sense the “neutral” rate. For essentially all of the 2010s, that number was constantly getting revised downward—in 2012 the median FOMC official thought it was 4.3%, by 2015 they thought it was 3.8%, by 2017 they thought it was 3% and just before the pandemic it had settled to 2.5%, where it has stayed ever since. That shift in medians belies shifts in the outer trends, however—at yesterday’s meeting, the lowest projection was only 2.4% and the highest was 3.8%. Seven participants put numbers above 2.5%, compared to just two who did so at the meetings two years ago. Yet perhaps what’s most interesting is the core disagreement between markets and the Fed over where long-term interest rates must go—even the participant with the highest long-run rate projection at 3.8% put a number well below current 30-year interest rates at roughly 4.4%. What’s behind this discrepancy?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.