The Fed's $300B Emergency Response

The Fed Has Lent $300B in Emergency Funds to Banks in the Wake of Silicon Valley Bank's Failure. Will it be Enough?

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 24,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

For the first time since 2020, the Fed is rushing in to backstop the US banking system. Several major regional banks are struggling in the wake of last week’s collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, and the distressed remains of those failed institutions are still being managed by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). The Fed committed to protecting banks and the financial system throughout the crisis, and it has backed up those promises with strong material actions—supporting the FDIC, opening up a new bank lending facility last weekend, easing the conditions of banks’ emergency credit lines, and promising liquidity to any depository institution in distress.

As of Wednesday, they had also backed up those promises with more than $300B in fresh loans for American banks—more than double the amount of direct credit created at the height of the pandemic in early 2020. So far, that has worked to stem the crisis—no more banks have fallen in the week since the FDIC, Fed, and Treasury got together to respond to the crisis—but many banking institutions still remain at risk. So will the Fed’s $300B emergency response—and the range of new policies they’ve enacted—be enough to stop the crisis?

Breaking Down the Fed’s Emergency Lending

The Federal Reserve had initiated more than $300B in secured direct lending to the banking system as of Wednesday—more than at any time since the Global Financial Crisis—in an effort to stem the fallout of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank’s failure. More than $11.9B in lending came from the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP)—the newly created facility that lets banks pledge government-backed securities at par for loans of up to one year. However, the majority of the Fed’s lending—$295B—came from the discount window, the Fed’s collateralized direct lending facility historically reserved for providing emergency liquidity to banks. The Fed lent $142B to the FDIC-owned bridge banks for SVB and Signature and another $152B to private banks via the discount window. One private bank likely makes up the bulk of that $152B in private borrowing—First Republic, who put out a statement saying their discount window borrowings had varied from $20B to $109B since Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse.

The vast majority of that emergency lending came in the form of very short-term loans—$290B of the lending matures within 15 days, a record high, and only $5.4B matures between 16 and 90 days, almost all of which is likely discount window lending. $11.9B matures between 3 months and 1 Year, which practically exactly matches up with the BTFP lending.

The Fed intentionally doesn’t publish immediate breakdowns of which institutions they’re lending to and how much they’ve borrowed, but by looking at data on total assets from the regional Fed banks we can get a general idea of who is getting liquidity from the Fed. Looking at the line item that includes discount window lending and BTFP funding, we can see that the lending is not evenly distributed nationwide but rather heavily concentrated in just two Fed banks. The San Francisco Fed, which has jurisdiction over SVB and First Republic, saw its assets increase by $233B, and the New York Fed, which has jurisdiction over Signature, saw its assets increase by approximately $55B. That doesn’t necessarily mean all the lending is concentrated in SVB, Signature, and First Republic—several west-coast regional banks have also appeared in distress and the New York Fed has jurisdiction over many financial institutions that are not necessarily New York-exclusive (for example, most Foreign Banking Organizations)—but it does mean the crisis hasn’t necessarily resulted in banks across the country borrowing from the Fed.

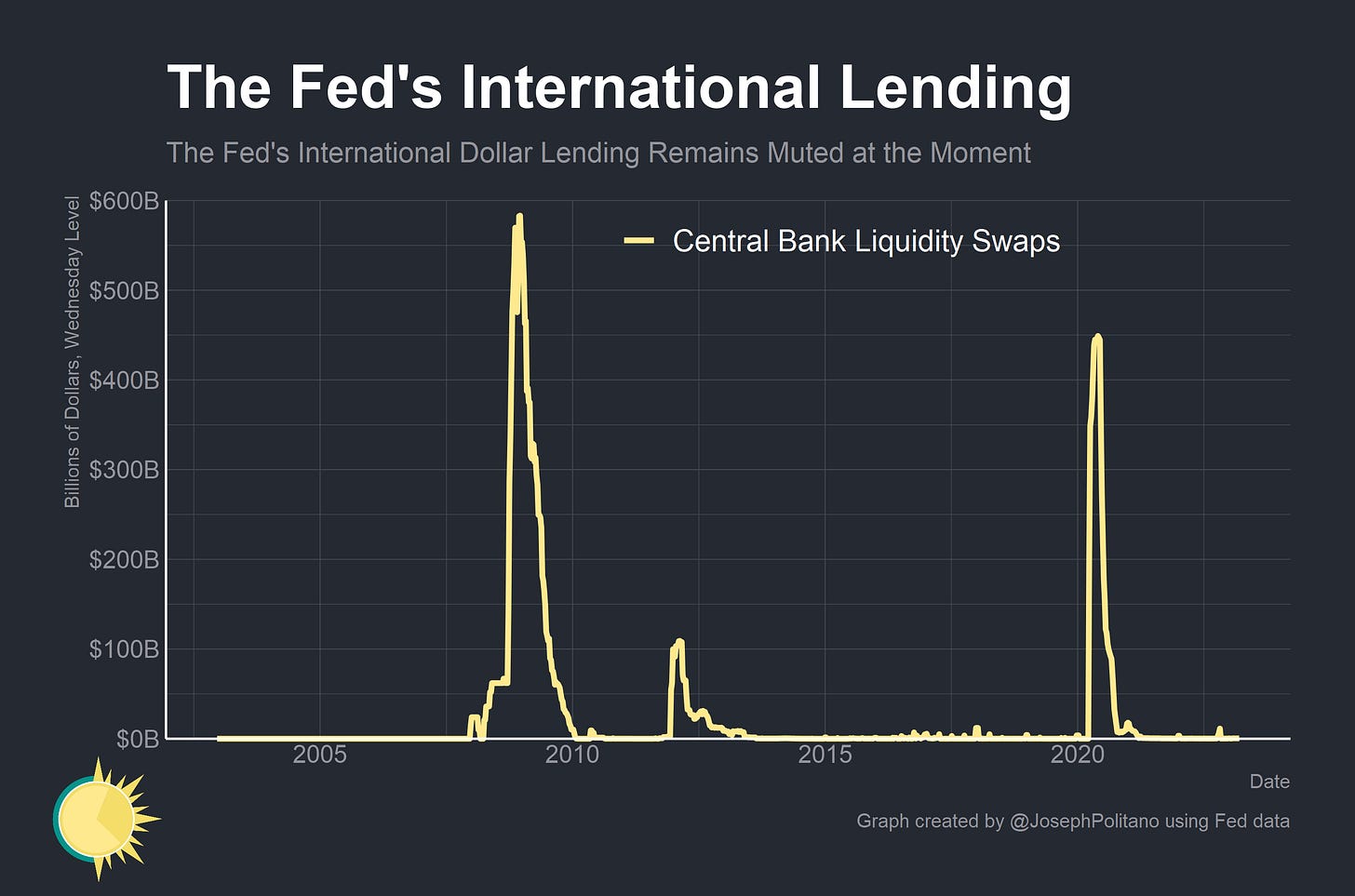

There also hasn’t yet been much additional borrowing through the Fed’s dollar swap lines (tools that foreign central banks can use to make dollar-denominated loans to foreign banks). Although recent weakness at foreign financial institutions like Credit Suisse could require the use of swap lines soon, their current disuse means the crisis has thus far been mostly contained to American shores, and the main recipients of Fed emergency funding are American banks borrowing from the discount window.

Understanding The New Era of the Discount Window

In many ways, the Fed was caught off guard by the collapse of SVB and the risks to the banking system in its aftermath. Regulators had gone easy on smaller “regional” banks under the misguided idea that their failures would not represent systemic threats to the financial system, and the Fed believed the pace of rate hikes had not been too fast to destabilize the banking system. However, in one way they were remarkably prescient—the Fed has been trying to institutionalize reforms to the discount window designed to improve financial stability in the aftermath of the early-COVID financial crisis. Today’s unprecedented use of the discount window partially reflects the desired results of those reforms.

In the Federal Reserve’s early years, a large number of institutions would be borrowing from the discount window essentially at all times—the window was more of a normal tool of monetary policy rather than an emergency backstop to the financial system. By the late-1920s, the Fed started discouraging the constant use of the discount window under the theory that overreliance was breeding financial stability risks and that the tool had outlived its usefulness in an era where the Fed set policy rates by injecting or removing bank reserves from the system. Anytime banks started borrowing from the discount window again, the Fed would intensify requirements, increase surcharges, or place more restrictions on lending to push banks away. This created a serious problem—because the Fed heavily discouraged the use of the discount window and overall use was extremely low, any bank attempting to borrow using the discount window for genuine emergencies would face significant stigma.

By borrowing from the Fed, a bank signaled that they were in a truly desperate situation and had no other options. Shareholders, creditors, depositors, and even government regulators would not be kind to you if they found out you had used the discount window—it was essentially a fireable offense for bank executives. The consequence was that even distressed institutions that came under pressure through no fault of their own would choose to bear unnecessary financial risk rather than ask the Fed for help—making the financial system as a whole more unstable.

In the wake of the financial crises of early 2020, the Fed made several reforms to the discount window to encourage more use among banks and reduce the stigma associated with borrowing from the Fed. First, the maximum term was extended from overnight to 90 days, enabling longer and more flexible borrowing by banks. Second, the “penalty rate” assessed on discount window borrowing was substantially reduced so that the cost of borrowing from the Fed was no longer substantially larger than market interest rates—as of today, the discount window’s primary credit rate is only 0.1% above the interest rate the Fed pays on bank reserves, compared to 0.7% before the pandemic.

Although the stigma surrounding the discount window persists, it has waned since the pandemic—more than 60% of banks said they would borrow from the Fed if market conditions caused funding to be scarce back in March 2021, and banks were regularly borrowing billions of dollars from the discount window before SVB’s collapse. Further changes to ease collateral requirements in the wake of SVB’s collapse will likely encourage more discount window use and help reduce stigma. That so many banks feel the need to use the discount window is a bad sign for America’s financial health, but that they are using the discount window rather than trying to go it alone without the Fed’s help is a good sign. The irony, however, is that the BTFP may end up inheriting many of the stigma issues that plagued the discount window, especially given the facility’s association with SVB’s collapse. However, the $11.9B in takeup suggests banks aren’t excessively worried about being seen borrowing from the Fed and is a positive sign for financial stability. If stigma becomes an issue again, the Fed might try to resuscitate or adapt the Term Auction Facility—a Great Recession-era program where the Fed would auction off a set amount of collateralized loans to banks in order to prevent any one financial institution from being tarred by the stigma of asking to borrow from the Fed. However, the Fed is likely to perceive persistence in discount window usage as a sign the system is working as intended for the time being.

Conclusions

So far, the Fed’s interventions have been successful in preventing a catastrophic tightening of financial conditions—although spreads on corporate debt have increased meaningfully since the failure of SVB, indicating worse borrowing conditions for major companies, the level is still below the recent July and October highs. But that shouldn’t be mistaken for a sign that the crisis is over—First Republic, for example, had to take in $30B in deposits from a group of other major banks in addition to the billions borrowed from the Federal Reserve. Several banks still remain at risk, and it could take time for the impacts of the Fed’s emergency measures to stabilize the banking system (all of which is a topic I intend to cover in the next edition of the newsletter).

One thing is clear, however—the ongoing effects of the SVB crisis have worsened financial conditions while also reducing interest rate expectations for the near future. On March 8th, interest rate futures markets expected the Fed to most likely going raise rates by 0.5% at next week’s FOMC meeting—today, they think there is a good chance there will be no rate hikes at all. The two-year Treasury yield fell more than 1% and has been highly volatile over the last week. Banks were already tightening their lending thanks to their worsening economic forecasts—and the events of the last two weeks are not likely to make them more excited about future economic prospects. Whether the Fed’s emergency efforts are enough to restore confidence in the financial system will come down to whether banks can return to stability without causing a credit crunch large enough to drag down the US economy.

Your coverage of these events has been some of the clearest and most helpful. Great work!

nice work joey