The Fed's Plan to Rescue the Banking System

How the Federal Reserve, Treasury, and FDIC Hope to Prevent a Bank Panic in the Wake of Silicon Valley Bank's Failure

In the aftermath of Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse last week, the US financial system was at risk of a full-blown banking panic. Once people lose confidence in one bank, it doesn’t take a lot for them to lose confidence in many banks—and for runs to kill even healthy financial institutions. So regulators had to come up with a plan—and one with enough shock and awe to restore confidence in the banking system.

Silicon Valley Bank was declared a systemic risk to the financial system, enabling the FDIC to guarantee that all of Silicon Valley Bank’s depositors—even those with balances in excess of the FDIC’s $250k limit on insured deposits—would be made whole and have full access to their funds on Monday

Signature Bank—a New York-based commercial bank with $110B in assets, deep ties to the crypto industry, and a significant amount of uninsured deposits—was also closed down and declared a systemic risk to the financial system, marking the third failure of a tech-related bank in less than a week. All of Signature Bank’s depositors will also be made whole.

The Federal Reserve would make additional funding available to banks through the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP), offering loans of up to one year to depository institutions that pledged any collateral eligible for open-market operations. Critically, that collateral will be valued at par instead of at fair value, meaning that banks with large unrealized losses on high-quality held-to-maturity assets thanks to rising interest rates will be able to borrow from the BTFP as if those assets had not lost value. The Department of Treasury is putting up $25B from the Exchange Stabilization Fund to backstop the program, but the Fed does not anticipate needing to draw on these backstop funds.

In broad strokes, depositors at SVB and Signature will be made whole, systemwide deposits will be backed by the BTFP facility and an implicit guarantee from the FDIC, and shareholders and unsecured debtholders in Signature and SVB will go unprotected. The government took these extraordinary actions in the face of significant risks to the US banking system, and to understand the motivations and designs of these actions it’s important to first understand the risks of a broader panic in the wake of SVB’s collapse late last week.

Understanding the Risks of a Panic

Over the last two weeks, the stocks of most US banks have fallen significantly more than the market as a whole—with midsized banks hit especially hard as fears of a spreading panic started getting priced into markets. Seven US banks had seen falls of 20% or more by market close on Friday, with trading on Silicon Valley Bank halted before its eventual failure. The fallout risk from SVB’s collapse was especially hard on tech-adjacent lenders with similar problems, like the now-failed Signature bank, alongside regional lenders concentrated in California like Pacific Western, Western Alliance, First Foundation, and especially First Republic.

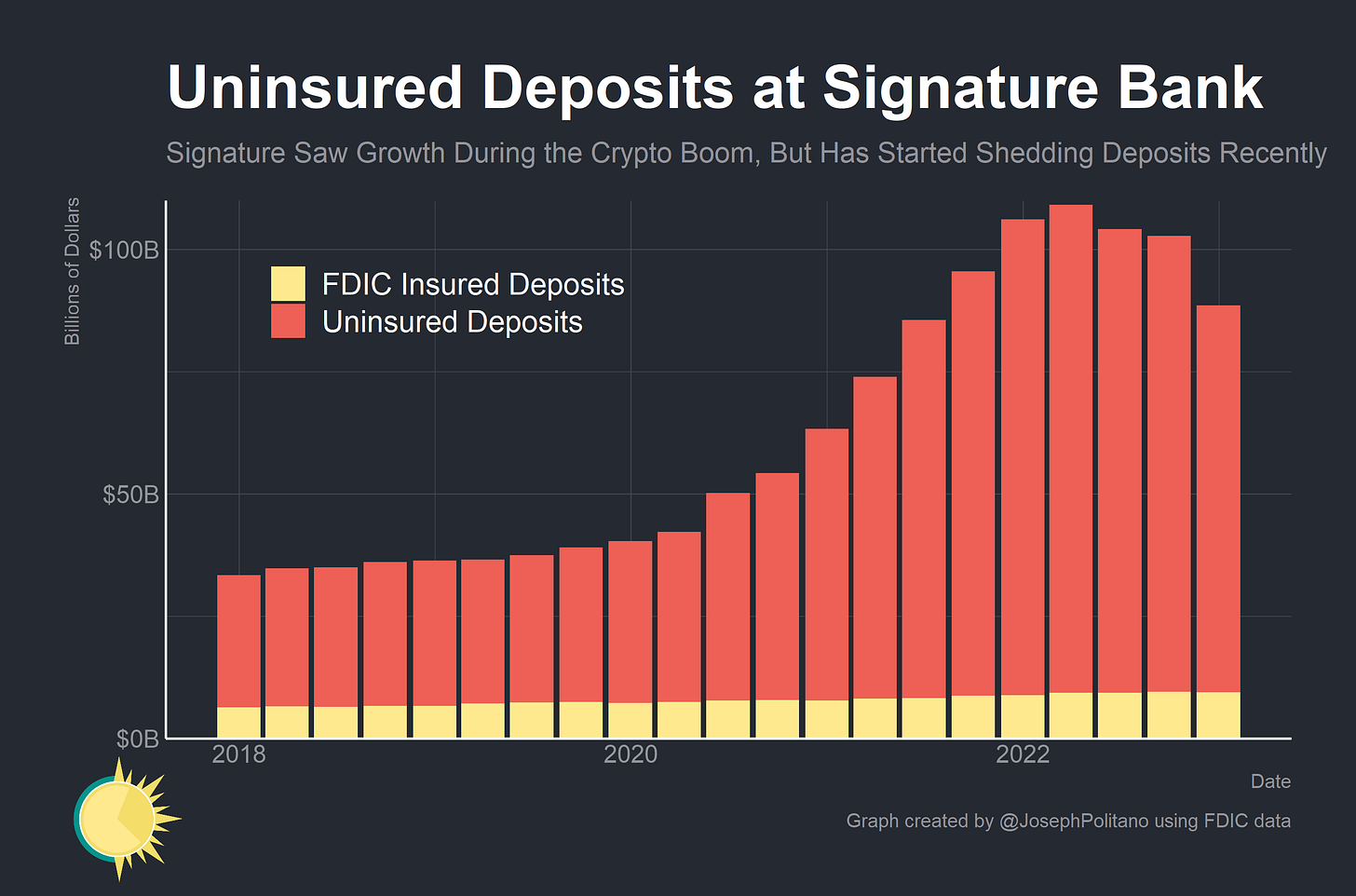

Indeed, the most important at-risk banks were First Republic and Signature, with $176B and $88B in deposits, respectively. The two had similar, though less extreme, versions of the problems that helped kill Silicon Valley Bank. In Signature’s case, the vast majority of its deposits were uninsured accounts belonging to businesses, it had high exposure to the crypto industry, which accounted for more than 1/5 of its total deposits, and had been losing deposits for several quarters amidst the crypto winter. First Republic had a much larger, more diversified, and growing deposit base but still was comparatively concentrated in high-net-worth Californians—plus, it was even more heavily invested in long-term assets (mostly about $120B in mortgages).

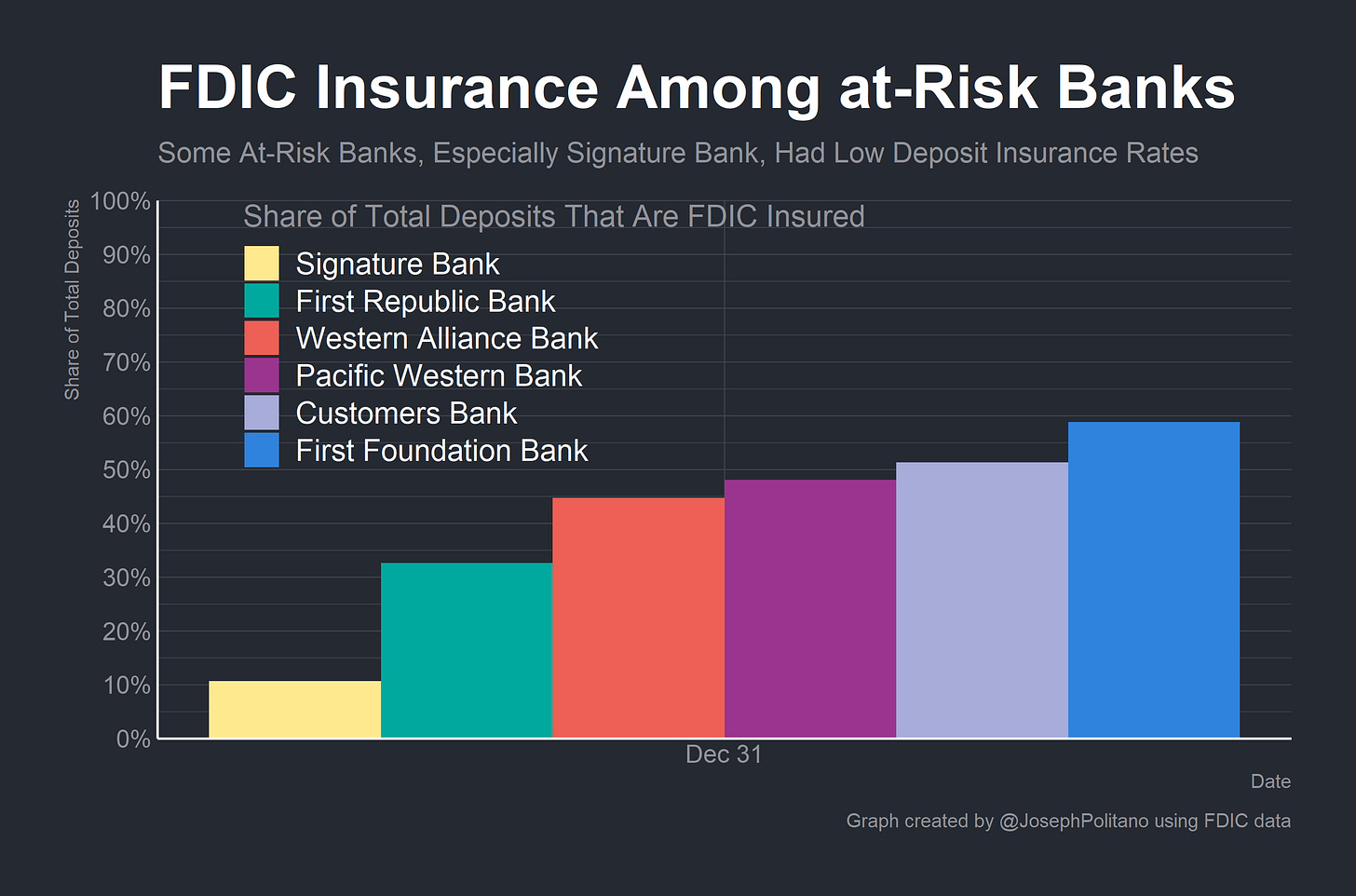

Both First Republic and especially Signature had relatively low shares of insured deposits—just a meager 10.6% in Signature’s case and 32.7% in First Republic’s case. Critically, both banks (but especially Signature) also had a deposit base that was much more coordinated than at most banks—if sentiment shifted among crypto companies, wealthy California tech executives, or New York businesses their deposits could flee nearly as quickly as SVB’s.

Signature Bank also fit the bill of a high-growth bank falling amidst the recent market downturn—total deposits had tripled from early 2018 and had been sliding throughout 2022 as the tech and crypto industries weakened. Although Signature was not in an immediate crisis as of Friday, internal sources suggested that it was also facing massive deposit outflows at the same time as SVB, and the FDIC evidently believed it would suffer further destabilizing withdrawals on Monday if it was not put into receivership.

First Republic’s problem wasn’t strictly a shrinking deposit base or an overabundance of uninsured deposits—it was more the direct spillover connections from among Bay Area industries and the banks’ concentration in long-term assets. At the end of 2022, more than 60% of First Republic’s assets had maturities of five years or longer, which is a higher share than SVB had before its collapse.

First Republic, like SVB, had also increased its concentration in long-term assets throughout the pandemic and was sitting on large unrealized losses as interest rates rose, but not to the same scale as SVB, which saw long-term assets rise from 33% of total assets at the end of 2019 to 55% in late 2022. However, First Republic still had to work with the Fed and JPMorgan Chase over the weekend to improve its liquidity profile in the wake of SVB’s failure, with the company accumulating $70B in unused liquidity as a buffer, so they clearly don’t feel out of the woods yet.

Still, the critical part about bank runs is that they can be capricious and random—it isn’t necessarily the bank’s actual financial health that causes a bank run but the perception of the bank’s health among depositors. Vanishingly few institutions would be able to survive the rapid amount of withdrawals that Silicon Valley Bank experienced—and the lineup of at-risk banks in many ways reflects institutions that, regardless of their direct financial health, would be most susceptible to another run.

Understanding the Plan

So how is the joint Fed-Treasury-FDIC plan supposed to help?

The first mechanism is by making more explicit the implicit policy of always making depositors whole. In practice, the FDIC has worked hard to prevent all depositor losses post-2008, but clearly the general public does not believe this implicit guarantee or they wouldn’t have started the run on SVB in the first place. Backstopping depositors at SVB and Signature should make uninsured depositors at other institutions feel more secure, which makes them less likely to pull deposits, which makes it less likely that more banks fail due to runs.

The second mechanism is the previously-mentioned Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP), the key part of which is the ability for depository institutions to borrow using collateral at par value instead of fair market value. That’s a big deal because of the popularity of held-to-maturity securities on banks’ balance sheets today—assets that get valued at par instead of fair market value for many banks in exchange for being held on the bank’s balance sheet until full repayment. In essence, this is an extremely large easing of collateral requirements—if a bank bought a $100 low-yield Treasury bond in 2020 that now has a fair market value of $80 thanks to rising rates, the BTFP enables them to borrow $100 against the Treasury instead of the usual $80.

Since banks have about $620B in unrealized losses on securities as of the end of 2022 (about 2.6% of total assets) this should help shield institutions from the kind of emergencies that Silicon Valley Bank faced—ones where depositors worried about unrealized losses flee en masse and force the bank to realize losses by fleeing. Ideally, banks that are insolvent mark-to-market with large held-to-maturity portfolios could borrow against their securities at par to meet depositors’ needs and hold the securities over a long enough time period to make back the money required to become mark-to-market solvent again.

This represents a large shift in Fed policy in a few ways—first, instead of working to protect banks against credit risk as in prior crises the Fed is now also essentially explicitly looking to protect banks against interest rate and duration risk. Second, it works against one of the oldest aphorisms in central banking—that institutions like the Fed should lend at penalty rates even in a crisis to prevent commercial banks from becoming overreliant on central bank lending programs. At BTFP, although funding rates would be much higher compared to deposits, they would still be low compared to historical norms and especially low when considering the generous effects of valuing securities at par in today’s higher-rate environment. Combined with ongoing changes to the discount window—the Fed’s emergency lending facility—it paints the picture of a central bank that has firmly decided to emphasize stability in the financial system.

Move Fast and Fix Things

So will it all work? Hopefully—of the possible government responses to the crisis, this one is much stronger and faster than expected. But it is hard to know right now—again, bank runs can be capricious and random and it is hard to gauge depositors’ reactions to prevention efforts in real time. Still, these are strong material actions with significant monetary backstopping from the government—exactly what public authorities should do to try and prevent banking panics. So the chances of panic have declined since Friday but it’s worth keeping an eye on at-risk banks for now, just in case.

Broadly, it’s hard to tell precisely what all this means for the Fed’s upcoming decisions on interest rates given the significant volatility, but on net it looks very likely to result in fewer hikes. Talk of a 50bps (0.5%) interest rate hike at the Fed’s March meeting has faded dramatically and as of early Monday 2-year bond yields have fallen 90bps over the last week. Still, it’s worth taking a broader view of the situation. The fall of Signature and Silicon Valley Bank is historically notable for a few reasons.

For one, it certainly represents the largest episode of crypto financial contagion in the traditional banking space. Although none of the banks collapsed due to losses on loans to crypto companies or wrong-way bets on the value of cryptocurrencies, their failure is an indirect consequence of the crypto financial crisis earlier this year. FTX’s collapse led to massive deposit outflows for Silvergate, Silvergate’s failure led to a crisis in confidence at Silicon Valley Bank, and Silicon Valley Bank’s failure led to the failure at Signature. It’s ironic that the proximal vector for crypto contagion was normal banking problems like duration mismatches and deposit outflows rather than some novel cryptocurrency financial product or lending to crypto firms, but nonetheless it will likely reinforce the desire for many traditional banks to stay as far away from crypto as possible at the moment.

For two, it likely portends a significant regulatory crackdown on mid-sized US banks. Partially thanks to deregulations in 2018, Signature and SVB were not stress tested, nor were they subject to regulations like the Liquidity Coverage Ratio or Net Stable Funding Ratio in the same way as large US banks like Bank of America. The logic was, even at hundreds of billions of dollars in size, banks like Signature and SVB were too small to pose a systemic risk to the financial system if they failed. Well, here we are today and the FDIC is saying their failures posed such systemic risks that it necessitated a large intervention to prevent panic. If the government treats them as systemically important in liquidation, it will almost certainly have to start treating them as systemically important in regulation.

Perhaps most importantly, the fall of these banks should be a wake-up call that financial flows and financial information can move faster than ever now. The run on Silicon Valley Bank happened over the course of just hours in VC group chats, social media networks, and other online spaces. Within 24 hours, 1/4 of the bank’s deposits were moving out the door and a 40-year old financial institution was on its deathbed. The FDIC, Fed, and Treasury moved in extremely quickly to stem the fallout of the SVB crisis—but they might have to get used to a world where they have to move even quicker, especially in the near future.

Outstanding explanations, and the graphs are excellent! 👍🏾

Great article!