The Gamification of Finance

How Social Media, Zero-Commission Brokerages, and the "Democratization of Finance" Have Changed the Investing World Forever

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

In December 2014, Robinhood launched on the AppStore with the mission to “democratize finance for all.” The company introduced zero-commission trading and relatively low account minimums in a bid to attract users for whom traditional financial institutions were too expensive and cumbersome. This gamble proved nothing short of an incredible success—in two years Robinhood’s valuation crossed $1 billion and other brokerages were forced to dramatically lower their commissions in order to compete. Today, Robinhood has more than 22 million funded accounts and nearly 19 million monthly active users.

As a result of rising social media use and increasing access to the finance world, investment and trading communities sprung up on a variety of social media networks: Fintwit—finance Twitter—alongside content creators on YouTube and now-famous Reddit communities like WallStreetBets. People shared investment ideas, discussed recent market moves, and posted their incredible gains or devastating losses. The rise of the crypto economy also increased speculative fervor across digital communities, while corporate titans like Elon Musk became social media stars. The pandemic, by causing extreme shifts in markets while leaving many people bored, alone, and with too much time on their hands, only accelerated the growth of online financial communities.

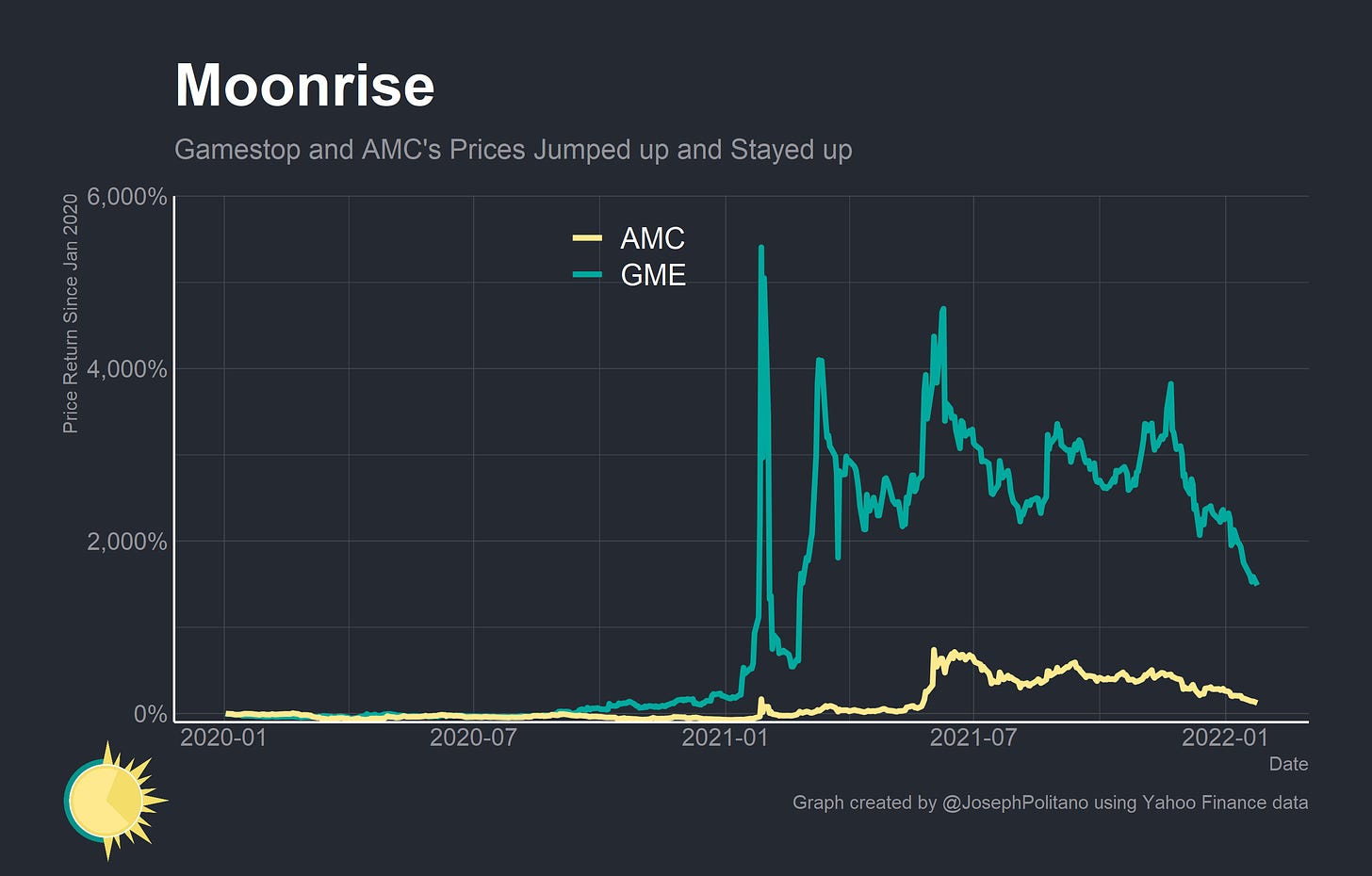

All of this came to a head in January 2021 when GameStop, a struggling video game retail company, became the focal point of the financial world. So the story goes, hedge funds had shorted the stock—borrowing and immediately selling shares in a bet that the GameStop’s share price would decline. Users on WallStreetBets saw the extremely high levels of short interest (more shares were sold short than existed) as an opportunity. If they could push the price of GameStop shares higher, short sellers would have to buy at the higher prices to cover their positions at significant losses. So they bought GameStop en masse, causing its price to rocket at the expense of the Wall Street hedge funds that had bet against the company. GameStop shares went from $20 pre-squeeze to nearly $500, and after its success traders moved to other stocks with significant short interest (like struggling movie theatre company AMC). That was, until Robinhood and other brokerages completely suspended trading in GameStop, AMC, and several other “meme stocks”—effectively cutting off momentum in the meme frenzy.

But that’s just a story—and to tell the story of the story, we’re going to have to start from the beginning.

The Democratization of Finance

The technological advantage of investors being able to band together through an easy-to-use app seems like it’s making profitable day trading harder rather than easier due to the effects of attention on buying and selling behavior.

Ben Felix, Commission-Free Day Trading

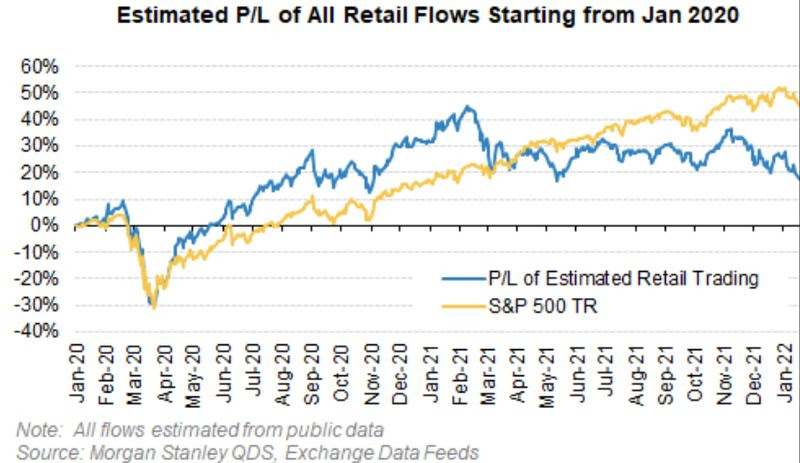

Trading is, for the vast majority of people, a money-losing proposition. Decades of academic research show that retail investors who attempt to pick their own stocks trail risk-appropriate benchmark indexes while those who trade frequently perform even worse. This shouldn’t be terribly surprising—professional fund managers consistently underperform indexes, so why should the average person be able to outperform? The essence of the Efficient Markets Hypothesis is that because the price of an asset reflects all relevant available information, investors cannot earn reliable alpha (return in excess of a risk-appropriate benchmark index). Real-world markets can’t be perfectly efficient, but they are close enough that alpha is generally extremely difficult to obtain. Those who do outperform major indexes tend to do so because they took on additional risk (like Warren Buffet with value investing), unearthed new information (like Renaissance Technologies’ famed Medallion fund), or simply got lucky.

Robinhood emerged at a time where low-cost passive index funds were taking the financial world by storm. The relative underperformance of costly actively-managed funds and the rise of low-cost index fund providers like Vanguard led trillions of dollars of everyday retirement savings to be piled into index funds. Robinhood tasked itself with tearing down one of the financial world’s last barriers to entry for normal people: the high cost of trading and opening a brokerage account. Traditional brokerages had no interest in managing millions of accounts with $500 each and so focused on a smaller fraction of higher-net-worth individuals. Many brokerages were clunky and charged large fees per trade, making them inaccessible to young, tech-savvy, and lower-net-worth users.

A large part of the appeal is not so much “finance is interesting”, it’s that trading stocks or crypto seems to be an easy way of making money. Which, obviously, I don’t think is true.

Bringing brokerages to smartphones, however, began to put a dent in the trend towards passive investing. People who trade on their phones are more likely to purchase riskier, popular, and lottery-like assets. They’re also more likely to chase past returns, succumbing to well-known behavioral biases that impede investor performance. These effects may not be transitory either—investors who start trading on the phone begin to exhibit similar behaviors on other platforms. Robinhood currently has 18.9 million monthly active users out of 22.4 million total funded accounts, meaning that most users are checking their accounts frequently—something that also lowers long-run returns. Active trading started becoming more of an alluring proposition for many people—a way they too could get rich quickly.

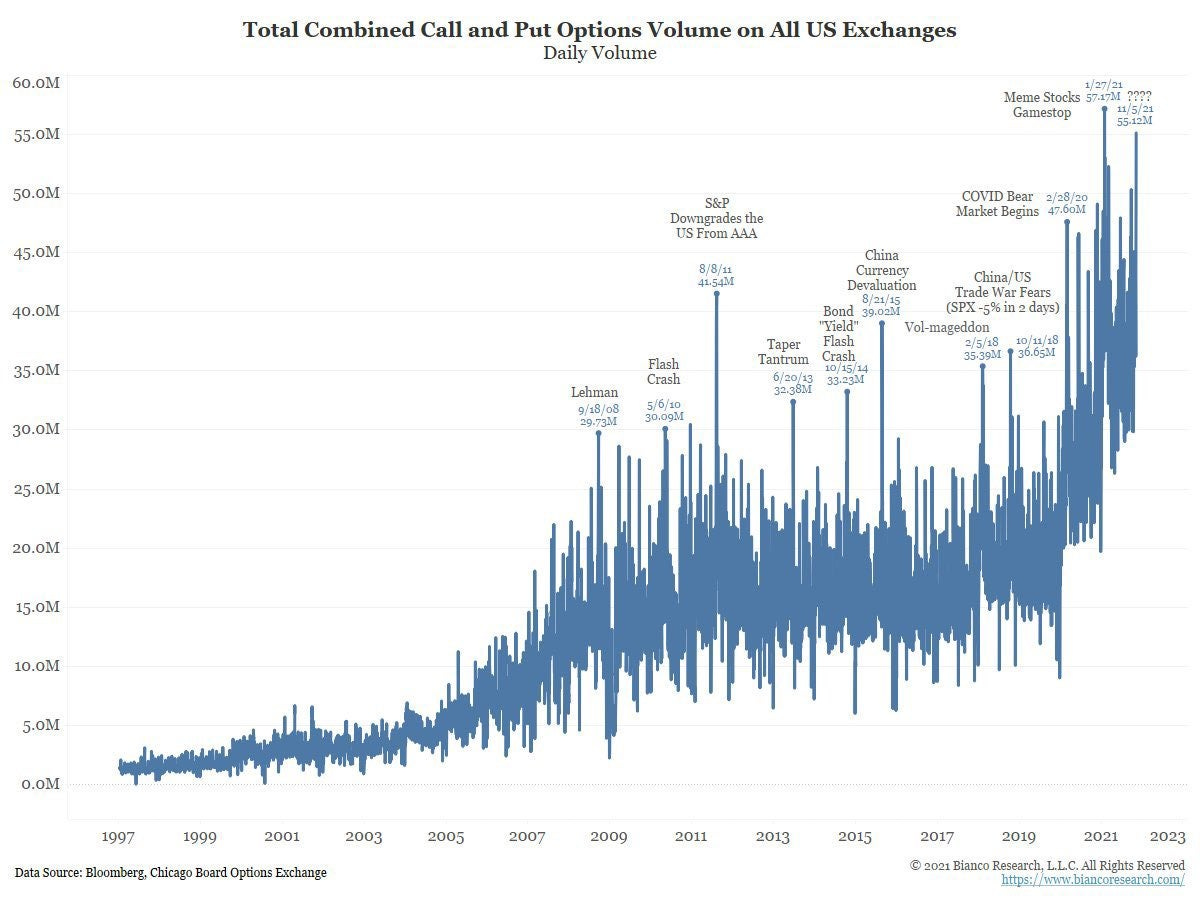

Over time, users of zero-cost brokerages began moving on to riskier and more volatile financial products. Put and call options, high-risk financial derivatives that are normally used for hedging, were increasingly used by retail traders to make levered bets on the movements of different stocks. There was an explosion of meme coins to accompany the already-volatile cryptocurrency market. Critically, Robinhood makes part of its money through Payment for Order Flow (PFOF), whereby the brokerage is compensated by market-makers for directing trades their way. The process is legitimate, an improvement on the hefty transaction fees of bygone eras, and likely cheaper for users than other options, but it still leaves Robinhood with an incentive to get users to trade as often as possible and to trade the riskier, less-liquid assets that market makers are willing to pay more to have routed their way. Last quarter, $164 million of Robinhood’s transaction-based revenue came from options, with another $51 million coming from cryptocurrencies and $50 million coming from normal equities.

The Memification of Finance

Society has always been a war of memes, but before it was fought with sticks and stones. The internet, however, has arms-raced that fight to trench warfare of meme-driven brains in many areas. They’ve not yet captured all fields of thought, but I fear the meme trenches will only expand.

CGP Grey, Q&A with Grey, Meme Edition

With the rise in retail investing and proliferation of social media, corporate executives and high-profile investors became social media stars (and, to a lesser extent, vice versa). Elon Musk, the Technoking of Tesla (yes, that’s his official title), is unquestionably the biggest star of the finance social media world with a staggering 71 million Twitter followers.

The way finance works now is that things are valuable not based on their cash flows but on their proximity to Elon Musk.

Matt Levine, The Elon Markets Hypothesis

Elon’s social media status makes him a market mover throughout both the traditional and crypto financial worlds. His tweets about GameStop, Dogecoin, Bitcoin, and his own company Tesla have caused large, instantaneous responses from financial markets. Many crypto projects are functionally created with the express intent of riding on Elon’s coattails, and CEOs of other publicly traded companies try to associate themselves with Elon’s social media fame as much as possible.

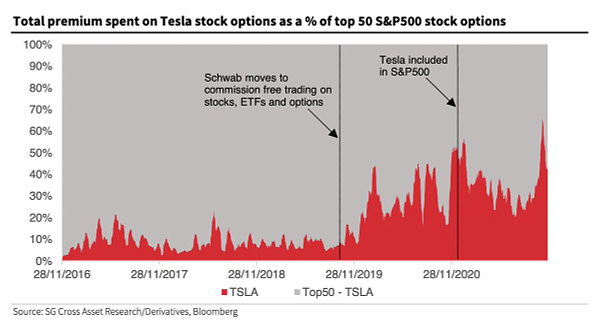

Elon has leveraged his social media fame into a group of highly-devoted retail investors, and he has leveraged those devoted retail investors into business success in a virtuous cycle. Tesla is a nearly $1 trillion company today, but it trades on an extremely high Price-to-Earnings ratio of about 270. For comparison, Apple’s Price-to-Earnings ratio is a measly 28 at the time of writing—making Tesla an extremely valuable company relative to its profitability. Part of this reflects high growth expectations, but part of this reflects Elon’s unique ability to attract retail investor capital at sky-high valuations. Tesla’s stock rose after it issued additional shares in December 2020, its third time raising capital that year at valuations that were even higher than those of today. Elon is able to deploy that cheap capital to rapidly expand real production, and he uses his social media fame to promote Tesla’s brand image and popularity.

Retail traders are emotionally invested in Tesla’s success thanks to their parasocial (meaning a one-sided relationship that a media user engages in with a media persona) connection to Elon Musk. Their emotional connection makes them stickier investors and willing to buy Tesla shares at high valuations. Seeing this, other corporate executives and fund managers took to social media to build social media followings of their own. Michael Saylor of Microstrategy Inc. built a following based on his company’s purchase of Bitcoin, Cathie Wood built a following based on her “disruptive” investment funds, and Chamath Palihapitiya built a following based on taking private technology companies public using Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs).

Part of our response as young people is to meme everything, and so I wouldn’t be surprised if that does become somewhat of an investment style.

The beauty and curse of social media is its ability to create narrative communities and parasocial relationships. Humans are narrative, social, and tribal creatures; we form communities based on in-groups and out-groups and learn from the stories members of our in-group tell us. Memes are not exclusively funny pictures but any shareable, mimicable, and adaptable short-form expression of complex ideas—and they are the lifeblood of narrative communication on the internet. An effective meme defines an ingroup and outgroup simply through who gets the joke (and thereby who will be shown the joke by social media content delivery algorithms) and communicates complex ideas through the medium of familiar templates (think about how many people use the famous “distracted boyfriend meme” to comment on a wide variety of different situations). Consider the recent crypto memes of WAGMI (“we’re all gonna make it”) and NGMI (“not gonna make it”). They clearly define an ingroup (the “we” who are invested in crypto or a specific coin/project), an outgroup (the “you” who are not invested), and tell a narrative story about the two groups (whether you will “make it” financially or socially) based on their relationship to the coin/project (which is implied to dramatically increase in value in the future).

Social media narratives underlie the explosion in the use of SPACs over the last couple years. In a SPAC, a shell corporation is listed on a stock exchange in order to finance the merger or acquisition of a privately held company. Since the SPAC launches without an real company attached and has to go searching for acquisition targets, they depend on investor’s faith in the SPAC’s founders to raise money. In the social media era, people with large, devoted digital followings—like Chamath Palihapitiya—can leverage the parasocial relationships they have with fans to acquire large amounts of funding for SPACs based only ideas and narratives.

Online communities form through constant exposure with memes that convey similar narratives. Eventually they start to self-catalyze. The memes get more popular, which drives previously uninterested people to participate in the community. These people become convinced of the core tenets of the community’s defining beliefs and they begin creating and sharing more memes. These memes convince more previously uninterested people to participate, and the cycle begins again. Which brings us back to GameStop and WallStreetBets.

The Gamification of Finance

WallStreetBets expanded dramatically early in the pandemic as COVID caused unprecedented movements in the stock market while cooped-up high earners had time and money to spare. It should not be forgotten that the subreddit also attracted many desperate people looked for ways to improve their financial situation and many people who lost social interactions during the pandemic and were looking to find a sense of community. The subreddit became infamous for traders who gambled everything they had on risky plays, either winning tons of money or (more likely) losing it all.

Our brains are still adjusting to this online space, and the way that they’re processing that is through a function of loneliness, through a function of “man, all I do is talk to people on Zoom all day.”

In late 2020 and early 2021, a subsect of Reddit’s WallStreetBets community became fixated on GameStop. The company appeared to be making some important changes to company organization and strategy in response to years of declining profits, and users on WallStreetBets saw the company’s record short interest as an opportunity. They began pouring money into the company’s stock in an attempt to squeeze short sellers, and the rest is history.

At the mania’s peak more than 750,000 individual accounts were trading GameStop, pulled in by the narrative—the meme—that they were sticking it to the hedge funds by buying the stock. If retail traders just drove the price high enough, they could wreck the suits on Wall Street while enriching themselves in one fell swoop. That meme started on WallStreetBets but rapidly spread: first across the rest of Reddit, then to Twitter and other social media platforms, then to Television and mainstream media outlets, then to the dinner tables of millions of Americans, and finally to the halls of Congress and the White House. Social media influencers like Elon Musk spread the meme even further, amplifying its reach by attaching their clout to the mania. The meme spread to other companies’ stocks—AMC, Blackberry, and other struggling retailers with significant short interest.

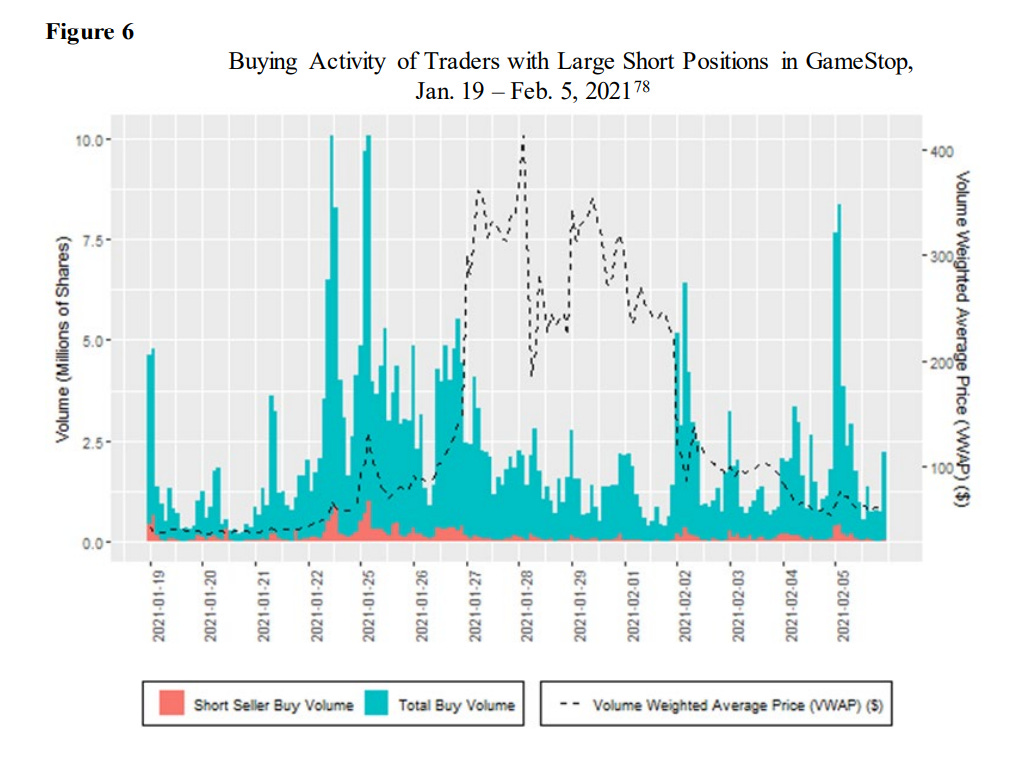

Whether driven by a desire to squeeze short sellers and thus to profit from the resultant rise in price, or by belief in the fundamentals of GameStop, it was the positive sentiment, not the buying-to-cover, that sustained the weeks-long price appreciation of GameStop stock.

SEC Staff Report on Equity and Options Market Structure Conditions in Early 2021

The beauty of social media is its ability to create narrative communities and parasocial relationships. The curse of social media is that those narratives do not have to be based in truth, and those communities can be lead astray by groupthink and ingroup-outgroup dynamics. The GameStop saga identified a clear ingroup—the online communities made of the forgotten, average Americans—and a clear outgroup—the Wall Street suits who had hollowed out the country. It identified a clear narrative: by buying GameStop stock you are sticking it to the hedge fund outgroup and enriching the online ingroup. This meme is what caused GameStop’s price to appreciate more than the actual short squeeze.

Indeed, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) report published in the aftermath of the GameStop episode shows that short seller buy volume made up a small proportion of total buy volume and that the majority of short sellers had capitulated long before GameStop reached his highest prices. It was retail buy volume, with an additional push from some institutions, that propelled GameStop’s share price to record highs. The short-squeeze was not the driving force behind GameStop’s price appreciation, it was an outpouring of money from retail traders that propelled the share price higher. Critically, it is the continued interest from retail traders that is keeping GameStop’s share price so high—as of writing, the company is trading at four times its pre-mania level and nearly twenty times its pre-pandemic level.

One of the main drivers of a gamma squeeze is an influx of call option purchases, which causes market makers to hedge their writing of the call options by purchasing the underlying stock, driving up the stock price in the process. While staff did find GME options trading volume from individual customers increased substantially, from only $58.5 million on January 21 to $563.4 million on January 22 until peaking at $2.4 billion on January 27, this increase in options trading volume was mostly driven by an increase in the buying of put, rather than call, options. Further, data show that market-makers were buying, rather than writing, call options. These observations by themselves are not consistent with a gamma squeeze.

SEC Staff Report on Equity and Options Market Structure Conditions in Early 2021

Just to put the other myths to bed, a gamma squeeze was also not responsible for the GameStop mania. A gamma squeeze is marginally more complicated than a short squeeze but essentially involves traders purchasing call options (a bet on a price increase of the underlying asset) from market-makers, thereby forcing market-making institutions to buy the underlying asset to hedge the call option they wrote. In purchasing the underlying asset the market maker drives the price up, so the purchase of enough call options by retail traders can pull the price higher. This would force short sellers to buy the underlying asset in order to hedge their positions, pulling the price even higher. However, retail traders were net buyers of put options and market makers were net buyers of call options—a scenario inconsistent with a gamma squeeze.

Finally, there was no conspiracy by hedge funds or other financial institutions to undermine the GameStop saga. When Robinhood and other brokers suspended trading on meme stocks it was not to protect the bottom lines of financial institutions that were suffering due to the squeeze. Instead, the extreme volatility forced clearinghouses to request massive deposits from Robinhood to cover the settlement period of trades in meme stocks. The deposit amounts were ten times Robinhood’s normal levels, and the company simply couldn’t foot the bill immediately.

When a naked short sale occurs, the seller fails to deliver the securities to the buyer, and staff did observe spikes in fails to deliver in GME. However, fails to deliver can occur either with short or long sales, making them an imperfect measure of naked short selling. Moreover, based on the staff’s review of the available data, GME did not experience persistent fails to deliver at the individual clearing member level. Specifically, staff observed that most clearing members were able to clear any fails relatively quickly, i.e., within a few days, and for the most part did not experience fails across multiple days.

SEC Staff Report on Equity and Options Market Structure Conditions in Early 2021

There was also no conspiracy surrounding failures to deliver. A failure to deliver occurs when one party in a trading contract doesn’t deliver on their obligation, and the conspiracy surrounding GameStop is that the short squeeze was partially undermined by short sellers simply failing to deliver when closing out their short positions. But the vast majority of failures to deliver were resolved quickly, and fails to deliver declined precipitously after the initial market turbulence.

This may seem like a lot of ink spilled just to debunk a couple misguided theories around the GameStop mania, but it is necessary in order to fight the pervasive narrative that has created a fundamental misunderstanding of the entire situation. The GameStop saga was not about short selling or sticking it to Wall Street—it was about millions of people becoming convinced by a meme on the internet to gamble what little money they had on the stock of a dying video game retailer. Wall Street won because, although a few hedge funds experienced large losses, brokerages, market makers, asset managers, and other large financial institutions profited handsomely from the rise in trading. Retail investors lost because they traded more—worsening their returns—and were drawn to extremely risky assets by the social media buzz.

In the end, what matters is what people think as opposed to what the actual facts are. As long as people think it’s “retail versus the suits” they don’t have too much of a consideration for the facts.

Critically, the GameStop story doesn’t end when it fades from the public eye in early 2021. WallStreetBets sat at under 2 million subscribers at the start of January 2021 and has since risen to nearly 12 million subscribers. “Superstonk” and “AMCstock”, the subreddits for GameStop and AMC, have risen to 730 thousand and 450 thousand subscribers respectively. Their front pages regularly contain posts predicting a total collapse of financial markets, the Mother of All Short Squeezes’ (MOASS—another meme), and a rapid rise in GameStop/AMC’s share price. They regularly promote conspiracy theories about financial firms, the Federal Reserve, and media organizations. It is this hyper-devoted niche internet community and the memes it believes in that keep GameStop’s share price high. Critically, they are communities for the lonely—with discussion thread, chatrooms, discords, livestreams, and more all working to build a shared digital space. Superstonk even got together to donate more than $100,000 to the charity Toys for Tots this winter.

When WallStreetBets went from 2 million to 9 million subscribers almost overnight most of the new subscribers did not have the sense for what was right or what was wrong. They were just coming from Twitter or Instagram, often inspired by meme pages or their friends. Those are the people I worry about.

Fundamentally, these people are victims of self-catalyzing, insular internet communities where users encourage each other to gamble money on extremely speculative investments to their own detriment.

Conclusions

The market is no longer driven by fundamentals—it’s driven by memes. No longer a metaphor, but a living structure—the stonk market.

Many people believe that a singular event—like a market crash, a recession, or the conclusion of the pandemic—will bring the meme trading frenzy to a close. I fundamentally do not see it that way. The primary drivers of meme trading are sociological forces brought about by the social media era and increasing access to financial markets. These are processes that were accelerated by the economic forces of the pandemic era, but were well in motion before the pandemic emerged. Corporate social media stars, online trading communities, and increasing access to financial services will only grow in importance as the digital age progresses. The meme trading frenzy won’t go away, it will simply move from asset to asset, platform to platform searching for another narrative to seize upon. Even the memes themselves are dedicated to keeping traders involved in the frenzy. “HODL” and “Diamond Hands” are both extremely popular memes for holding onto financial assets despite their large fluctuations in value. When people who you have a parasocial relationship with and the online communities you frequent are all constantly encouraging you to trade, it can be extremely difficult to quit.

Nor do I see the meme stock frenzy as something that is fundamentally disrupting the normal function of financial markets as a whole. While there is evidence that Robinhood day traders cause extra volatility in the ticker symbols they focus on, retail traders only make up a fraction of overall trading volume. While margin debt is at all time highs, it still represents a normal fraction of overall market value. The primary victims of the retail trading boom are the traders themselves, who are likely to suffer from lower returns thanks to their trading behavior.

Consideration should be given to whether game-like features and celebratory animations that are likely intended to create positive feedback from trading lead investors to trade more than they would otherwise. In addition, payment for order flow and the incentives it creates may cause broker-dealers to find novel ways to increase customer trading, including through the use of digital engagement practices.

SEC Staff Report on Equity and Options Market Structure Conditions in Early 2021

There are two primary beneficiaries of this retail trading boom. First are the financial institutions that are deploying behavioral nudges and gamification to encouraging their userbases to trade more. Every trade by a retail investor is more money in their pockets, and the riskier the trade the more money they make. The second beneficiary are the people who shape the social media narratives and—for lack of a better term—create the memes. Their ability to direct retail investor money will become an increasingly important part of corporate and fund strategy going forward. The parasocial relationships they develop with their audiences give them the unique ability to deploy cheap capital to affect outcomes in the real economy—all while enriching themselves.

In the social media age, it is important to remember that you are not immune to propaganda. Propaganda, in this case, does not exclusively mean political campaigns but any piece of information that furthers a particular narrative. The narratives that form on Twitter or Facebook may not be top-down ploys to shape public opinion, but the flow of information from content delivery algorithms nonetheless shapes and is shaped by the views of their users—whether these views are true or not. Some memes are innocuous, but others are deadly—and distinguishing between the two is increasingly hard in the extremely competitive attention economy. The natural tribalism of the human mind means that propaganda in the social media age is created in an extremely decentralized fashion. There are millions of tiny communities with their own ingroups and outgroups competing against each other for control of the narrative. All social media influencers—yes, this includes me—have biases, shortcomings, and incentives that make them imperfectly trustworthy institutions. The only way to stay safe in the modern era is to confront your own biases and susceptibility while constantly challenging your information sources.