The Great European Undershoot

The EU's Institutions Encourage Contractionary Policy, and the Results Have Been Catastrophic

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

From 1995 to 2007, the GDP per capita of the Euro area grew by about 1.8% every year. Since then it has barely grown at all.

The average European has $10,000 less in income than they would given the pre-crisis trend. Italy and Greece were reset back to mid-1990s levels of economic output. The European Union (EU) and the Eurozone were supposed to encourage economic growth, but even former world leaders like France were not spared from economic devastation. What caused everything to go so wrong?

The European project represents the most ambitious transnational integration effort ever undertaken. As a result, the EU’s economic institutions were forged through compromises that forced future policy to lean heavily conservative at every turn. The consequences came during the 2008 recession, when the European Central Bank (ECB) refused to take on its role as lender of last resort and implement sufficiently expansionary monetary policy. EU countries themselves could not use aggressively countercyclical fiscal policy without the ECB’s support, and the founding treaties of the EU further restricted member countries’ ability to borrow and spend. The near-collapse of the Eurozone in 2012 was an avoidable, but predictable, result of bloc’s macroeconomic structure. Repairing the damage and preventing the next crisis will require innovative policy and further integration of the Eurozone economies.

The Euro Crisis and the Great Recession

Mark Klein’s inaugural blogpost “Let’s Overshoot” outlines the effects of the Great Recession in the US clearly; GDP per capita growth broke a half-century long 2.2% growth trend and has never recovered since. The problem is the same throughout Europe - the growth trends of the postwar period were shattered by the recession and have never recovered to the pre-recession trend. However, the EU’s problems were compounded by the Euro crisis that almost tore the bloc apart in 2012. While the US merely lagged growth expectations, several European countries actually saw their GDP per capita shrink as a result of the crisis. The Portuguese and Spanish economies have only recently exceeded their 2007 real GDP per capita levels, and Italy never has. Greece was particularly devastated, becoming the first country in recorded history to be downgraded from “developed market” to “emerging market” by MSCI.

To understand the Euro crisis one must first understand the structure of the ECB and the critical differences between it and traditional central banks like the Federal Reserve. While the Federal Reserve is the sole central bank for the United States and operates to implicitly back the US government and all dollar-denominated markets across the globe, the ECB is a Frankenstein’s monster of many National Central Banks (NCBs) which are the exclusive shareholders of the ECB. The NCB governors are appointed by the national governments and had permanent voting rights before 2015 (nowadays they have rotating voting privileges with the largest countries able to vote more often). The European Council, which primarily comprises the heads of state of EU member countries, appoints the voting members of the ECB’s Executive Board. The result is a mismatch system of competing national interests that has proved unwilling to back Euro-denominated markets even within the Eurozone itself.

The spreads between 10 year bonds listed in the chart above reflect the difference between the nominal yields on German 10 year bunds and the nominal yields on 10 year bonds of other EU countries. Since Germany is the largest European economy and has an extremely small debt burden, its bonds are among the least risky and therefore usually have low yields. Before the Great Recession, spreads between German bunds and other countries’ bonds were extremely tight. This means that investors implicitly treated Italian, French, Portuguese and even Greek bonds as being approximately as risky as German Bunds. Investors believed that, implicitly or explicitly, the ECB would back the bonds of all Eurozone members equally and that no country would be allowed to default on its debt. This is implicitly how US Treasury markets work: there is zero risk that the US government will default on its debt as the Federal Reserve can always create bank reserves to purchase treasuries if necessary. The interest on 10 year bonds in the United States is therefore only a function of the expected future short term interest rates in the US, risks from the term length of the bond, and risks of inflation. While many investors expected the ECB system to work the same way, the developments in Greece after the Great Recession proved that the ECB would not explicitly back the debt of Eurozone member countries. Bond yields shot up as investors realized that they had to price in an additional risk - not the risk that national debts would be unsustainable in the long term, but the risk that certain EU countries could run out of Euros.

In the wake of premature monetary policy tightening by the ECB under Jean-Claude Trichet, spreads soared until the the ECB was forced to act. Even large European economies like Italy and Spain were seeing rapid increases in their bond yields. When Mario Draghi became president of the ECB, he rapidly realized that the only way forward was to have the ECB backstop the debt system. This culminated in a speech in July 2012 where Draghi said that the ECB would do “whatever it takes” to preserve the Euro. This, in essence, was the ECB announcing that they would not allow other countries, particularly the major nations in the Eurozone core, to fall victim to the same fate that befell Greece.

First, it is worth noting that the Euro crisis was not a sovereign debt crisis in the traditional sense. In a traditional sovereign debt crisis, a country is unable to maintain its debt balances without an extreme devaluation of its own currency. Faced with the option of runaway inflation or sovereign default, the country chooses default. The Euro crisis, particularly the Greek debt crisis, was closer but not quite equivalent to a balance-of-payments crisis. In a balance of payments crisis, a debtor country is unable to acquire enough foreign currency to service its current debt or imports without devaluing its currency.

Why wasn’t the Greek debt crisis a sovereign debt crisis? Principally, because the country generally could pay back its debt. Today, Greece is able to much more comfortably service its current debt with a much larger debt/GDP ratio and gross debt size than they had in 2007. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), net interest payments as a share of GDP, which I’ve previously explained is the best measure of national debt, was 4.3% in 2007 but only 3.6% in 2019. This is also with significantly lower inflation than pre-crisis; Greece experienced about 4% inflation from 2000-2008 but has never seen 2% inflation since 2012 and actually experienced several years of sustained deflation. The size of the debt itself was not the problem, the ability of the Greek government to get Euros was. In a usual balance of payments crisis, the country’s central bank would be forced to allow the country’s currency to devalue with respect to foreign currency in order to keep up the pace of imports or service its external debt. In the Eurozone, the Greek government was unable to do this - the Greek government does not have monetary sovereignty and cannot devalue the Euro with respect to the Euro. Even though their economy was strong enough to repay the debt in the long term, the country was not able to obtain enough Euros in the short term to prevent a default. However, unlike in a traditional balance of payments crisis, the core problem was not an unsustainable currency valuation or excessive external debt burdens but an unwillingness by the ECB to act as a lender of last resort to the Greek government.

European banks create Euros when they lend through the ECB system, and these banks are generally backstopped by the ECB in the event of a liquidity crisis. But countries within the Eurozone do not enjoy that same backstop with respect to their sovereign debt. When the Greek government could not repay its debt, the Troika of the ECB, EU Commission, and IMF required private bondholders to take a 50% haircut (reduction in the face value of the bond) before implementing the second bailout in 2011. It also imposed harsh austerity measures on the country that prevented it from effectively spending to close the output gap and boost economic growth. While it became clear after 2012 that the Troika would not allow the Eurozone to completely collapse, it also became clear that they were unwilling to back member countries’ debt 1:1. The predictable result is that, even today, spreads remain unacceptably high by pre-2008 standards: the spread between Italian and German 10 year bonds is nearly 1% at the time of writing.

The founding of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), which replaced the two temporary EU bailout funding programs, represented significant progress towards ensuring that no country would be at risk of total collapse again. The program created permanent emergency lending capabilities to rescue member countries in the event of another Greece-style crisis. The ESM, however, still implies that bondholders will have to take a haircut of some kind in the event of a “bailout”, threatens austerity measures on its beneficiaries, and does not have the sheer capital necessary to fully back large countries like Italy. Only the ECB, with the ability to directly create Euros, can fully back sovereign debt. The ECB chose instead to operate its quantitative easing (QE) purchases of government bonds through a capital key proportional to the size of member countries’ economies and populations instead of using these purchases to equalize yields. Allowing bond spreads implicitly acknowledges a risk of default in many EU countries that the ECB is unwilling to prevent.

It is unthinkable that the Bank of Japan or the Federal Reserve would simply allow the Japanese or US governments to default on their debt obligations, especially if preventing default had minimal to no associated inflation risk. However, that is exactly what the ECB did to the Greek government, and what they threatened to do to countries as big as Italy. Without the ECB reclaiming its role as lender of last resort for all national governments and explicitly closing the spreads between Eurozone countries, quality monetary policy within the EU is impossible.

The Maastricht Treaty

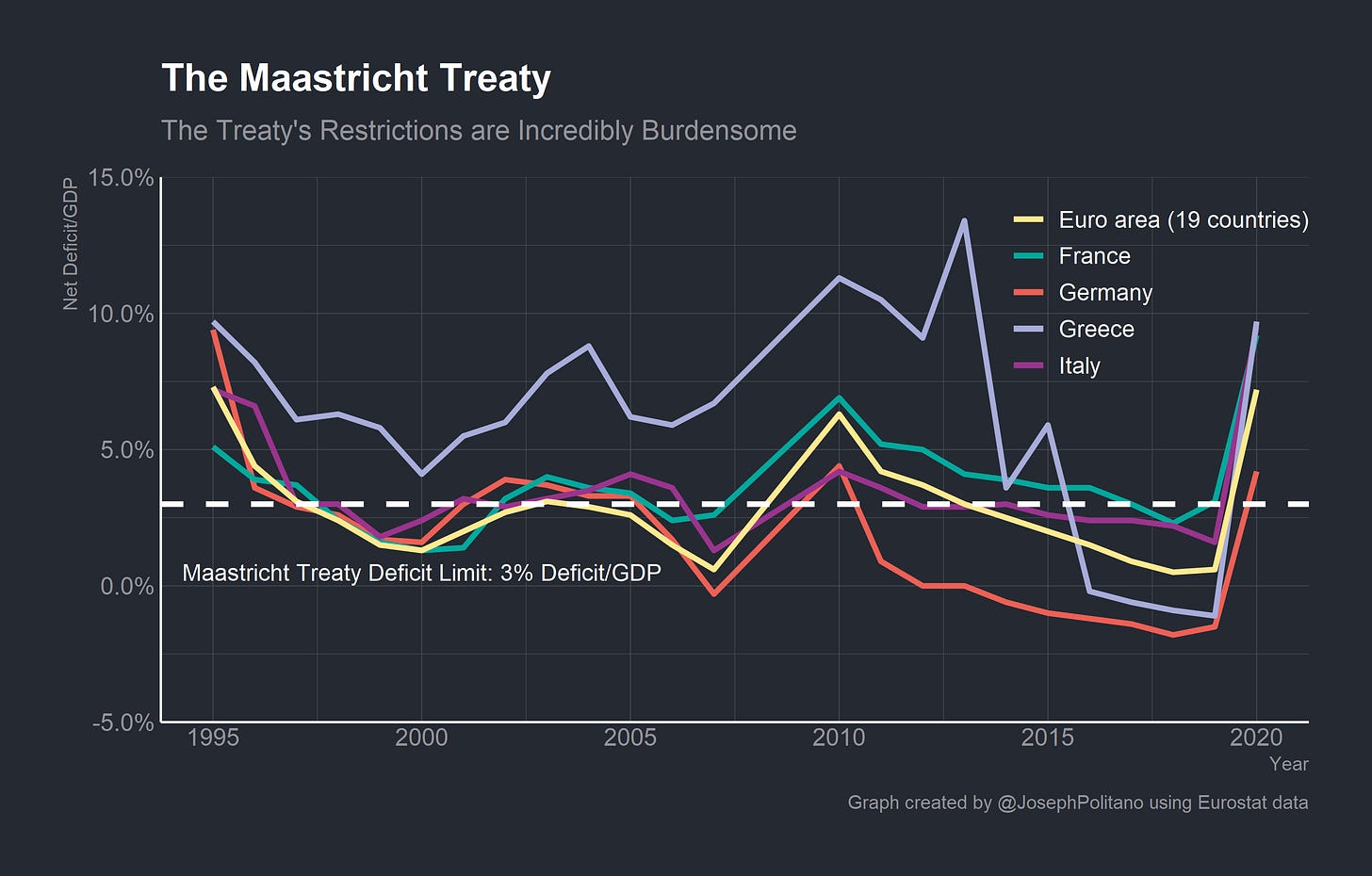

Another critical problem comes from one of the EU’s founding documents: The Maastricht Treaty. The treaty represented the next step forward in European integration upon its signing in 1992. It established the European Union officially, outlined the path forward to creating a monetary union, and laid out the creation of European citizenship. Nowadays, the treaty is mostly remembered for the extremely restrictive criteria imposed on prospective and current Eurozone members. In order to be allowed into the Eurozone, countries had to have a general government debt/GDP ratio of less than 60% and could not have a deficit of greater than 3% per year. The 60% and 3% numbers are both fundamentally arbitrary, and the measures selected are extremely incomplete. By looking only at gross general government debt to GDP, the Maastricht restrictions ignore interest expenses, general government assets, and the ECB’s holdings of government debt. Germany has been stuck slightly above the Maastricht treaty restrictions since the 2008 recessions, but has actually almost reached 0% debt/GDP when you account for their share of ECB assets. These restrictions are onerous, counterproductive, and based on terrible macroeconomic data points. Nevertheless, countries are threatened with fines and the implied loss of ECB support whenever they exceed the treaty’s restrictions and are put through the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP). This leads countries far below their potential output levels to engage in counterproductive austerity simply in order to satisfy arbitrary rules.

The enforcement of the Maastricht treaty itself is also arbitrary - nobody has ever been directly fined through the EDP measure - but countries are still brought in line by the mere threat that the ECB and the European Commission would stop backing the debt of any noncompliant country. The result is that countries like Italy have run primary surpluses (surpluses before accounting for gross interest expenses) almost every year since the creation of the Euro. Italy has been unable to use countercyclical fiscal policy to close their output gap, something that would actually improve both their economy and their debt sustainability. Germany is double bound by the Maastricht treaty and the Schuldenbremse (“debt brake”), the constitutional restriction from 2009 that forced Germany to avoid a structural gross debt/GDP ratio higher than 60%. The largest economy in Europe essentially prevented itself from using proper fiscal policy to close output gaps throughout the Euro. There may be ways around the debt brake, as Matt Klein explains, but the fundamental obstacle to optimal German fiscal policy is the political forces that created the debt brake, not legal debt brake itself.

The deficit restriction had also been onerous for many countries. It is worth noting the compounding nature of the EDP and the ECB in this case. When countries violate the debt/GDP limits from the Maastricht treaty, the mere threat that the ECB might not back their debt fully forces investors to price in a higher risk of default. That priced in risk drives up bond yields, increasing the interest expenses for countries like Italy to ridiculous degrees. As a result, their interest expenses rise and buoy their fiscal deficits. That’s how Italy can run decades of primary surpluses and barely stay below the treaty’s gross deficit limits.

It’s worth noting here the critical difference between the fiscal borrowing structure in the Eurozone and in America. In America, the federal government’s borrowing ability is implicitly backed by the Federal Reserve - the Fed will buy US Treasuries according to its mandate in order to encourage stable prices and full employment. States and local governments, however, are constrained by private markets and must rely on taxes, income from the federal government, and other streams of revenue. While the Federal Reserve occasionally intervenes in state and local credit markets, as it did during the pandemic, these interventions are explicitly authorized by the congressional and executive branches. States and localities can go bankrupt, and usually it is up to fiscal policy to provide funding in the case of emergencies. In the European system, however, countries exist in this middle zone where they are not fully backed by the ECB or any other fiscal authority but remain the largest government entities capable of borrowing in Euros. Only the ECB can create the Euros necessary to backstop national debts, and yet it chooses not to. Implicitly, the countries of the EU are closer to states than the federal government - their borrowing is constrained by their ability to obtain Euros from taxes and other streams of revenue, not by the optimal mix of monetary and fiscal policy needed to maximize stable growth.

The Sub-Optimal Currency Area

Economist Robert Mundell popularized the idea of an optimum currency area (OCA). An OCA is any geographical region where a single currency would maximize economic efficiency, and Mundell came up with several criteria for determining whether a certain area was an OCA:

High labor mobility

Capital mobility and wage/price flexibility

Fiscal risk-sharing

Coinciding business cycles

The Euro area struggles with many of these. While any EU citizen can move to any other EU country easily, in practice language and cultural barriers mean that workers are less likely to move than their counterparts in more linguistically homogenous countries like the US or Japan. There is minimal fiscal risk-sharing, as the EU itself spends little money compared to the national governments. While the federal government of the United States meaningfully redistributes money from rich to poor with no regards to state borders, the mechanisms for the EU to redistribute money from wealthy Germans to poor Italians are almost nonexistent. Capital mobility is relatively high (as analysts point out, the ability for investors to pull capital from the collapsing EU economies to the prosperous ones was a catalyst during the debt crisis), but wages and prices retain significant dispersion. Business cycles also barely coincide: Italy has basically undergone a decade-long recession while its German neighbors have grown slowly but consistently.

The result is that monetary policy cannot satisfy the needs of all countries at once. Different inflation rates across the Eurozone means that while nominal interest rates remain uniform, real interest rates across the bloc differ significantly. Even if real interest rates could be made consistent throughout the bloc, some economies likely need lower real interest rates than others and policy will therefore always be too tight for some countries. If monetary policy is too tight for Italy, growth and employment fall, which necessitates an even lower nominal interest rate to restore labor income growth. Every year monetary policy is too tight growth decreases further, pulling inflation and the optimal nominal interest rate again until the economy is stuck near the effective lower bound (ELB). The ELB represents the lowest possible nominal interest rate that a country can sustain without causing problems by passing negative nominal interest rates onto bank depositors. At the ELB the Maastricht treaty restrictions also prevent the Italian government from borrowing and spending sufficient funds to escape this liquidity trap. The result is an economy that is unable to boost aggregate demand enough to prevent secular stagnation.

Conclusions

The only way forward will require further integration within the EU and especially the Eurozone, but the terms of integration must change. The ECB ought to explicitly seek to close bond spreads between countries and backstop the national debts of all Eurozone members. The flexible approach that the ECB has taken to debt purchases during the pandemic has prevented another explosion of bond spreads, and this approach should be strengthened and institutionalized in the wake of its success. The authorization of more than a trillion euros in supranational EU common debt to fund the European recovery is another critical step forward. The common debt will be alleviate the burdens faced by member countries struggling in the wake of the Euro crisis and further harmonize the economic fortunes of the bloc as a whole. Critically, it will also give the the ECB an asset it can fully backstop and easily buy to stimulate the economies of all member countries without violating the capital key requirements for buying national debt.

The EU should also work to build mechanisms that guarantee the debt of national governments and alleviate the Maastricht treaty rules. The EU should transform the ESM into a fully fledged “European Monetary Fund”, an institution with the complete support of the ECB that will backstop the debt of any member country in the event of a crisis. That way no country will ever be tarred with long term economic harm due to short-term debt problems. This EMF in conjunction with the EDP can be used to ensure that member countries do not borrow and spend money wastefully, but their criteria for evaluation should be based on careful cost-benefit analysis and not the arbitrary numbers of the Maastricht treaty. To the extent that the treaty’s rules remain set in stone, EU policymakers should focus on crafting innovative solutions to work around the targets and weaken or eliminate the punishments for violating the rules. For example, the EU could use funds from the issuance of common debt to purchase and pay down national debt, and these newly issued EU common bonds could be swiftly bought up by the European Central Bank. In effect, the ECB would be paying down national debt in the same way that it currently does when it engages in QE, but this method would lower the gross nominal amount of debt owed by member countries while current QE does not. When countries do cross the into dangerous levels of debt the EDP should focus on encouraging productive investment and reducing waste, not slash and burn austerity measures to get below an arbitrary number. The threat of EDP fines should be used sparingly if at all by the EU commission, especially if the country in question is below potential growth, and there should never again be an implication that the ECB would not fully back the national debt of any one country.

The EU will never be a perfect institution. It is forged by a million tiny compromises, its policies and politics a bottomless well of asterisks, exceptions, and complications. The EU and ECB will never behave with the single minded focus and clarity of national governments and central banks. The promise of the EU lies in its ability to slowly wear away at the divisions between the people of Europe and forge a one of a kind institution that transcends arbitrary national divisions that have separated humans for millennia. To reach its true economic potential, the EU needs further integration, monetary policy that properly protects all citizens, and strong countercyclical fiscal policy. Without those reforms, the countries of the European Union will simply continue to undershoot their potential.

Great article. I first got aware of the problems discussed here a decade ago when reading MMT literature. Especially Bill Mitchell's blog. Besides all of that, this is the clearest explanation of the topic I've seen.