The Green Trade Wars

How the US and EU are Trying to Wrest Solar, EV, and Battery Supply Chains From China

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 35,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

The world has recently hit an exponential adoption curve for three key clean-energy technologies—solar, batteries, and electric vehicles. Indeed, progress has exceeded all but the most optimistic forecasts from a few years ago, bringing the items from fringe technologies to the centerpieces of global decarbonization efforts—and none currently shows signs of slowing down.

Global solar output has nearly doubled since 2019, and in some countries like Spain and Greece, it now accounts for more than 10% of annual electricity generation. Of the new utility-scale electric generating capacity planned in the United States this year, fully 1/2 are from solar projects. Costs continue their long march downwards, with the price of panels deployed in the US falling to a new low of $0.31 per peak watt last month, falling nearly 25% in nominal terms compared to pre-COVID.

Meanwhile, electric vehicle sales have gone from 2.2M in 2019 to 14M this year as estimated by the International Energy Agency. That means just under 1 in 5 new vehicles sold worldwide could be battery-powered this year, and EVs are now nearly 7% of new passenger vehicles sold in the United States with roughly the same share coming from hybrids. That global boost in demand for EVs has been so strong that the German statistics office has even had to revise its car manufacturing data methodology to account for their rapidly growing market share.

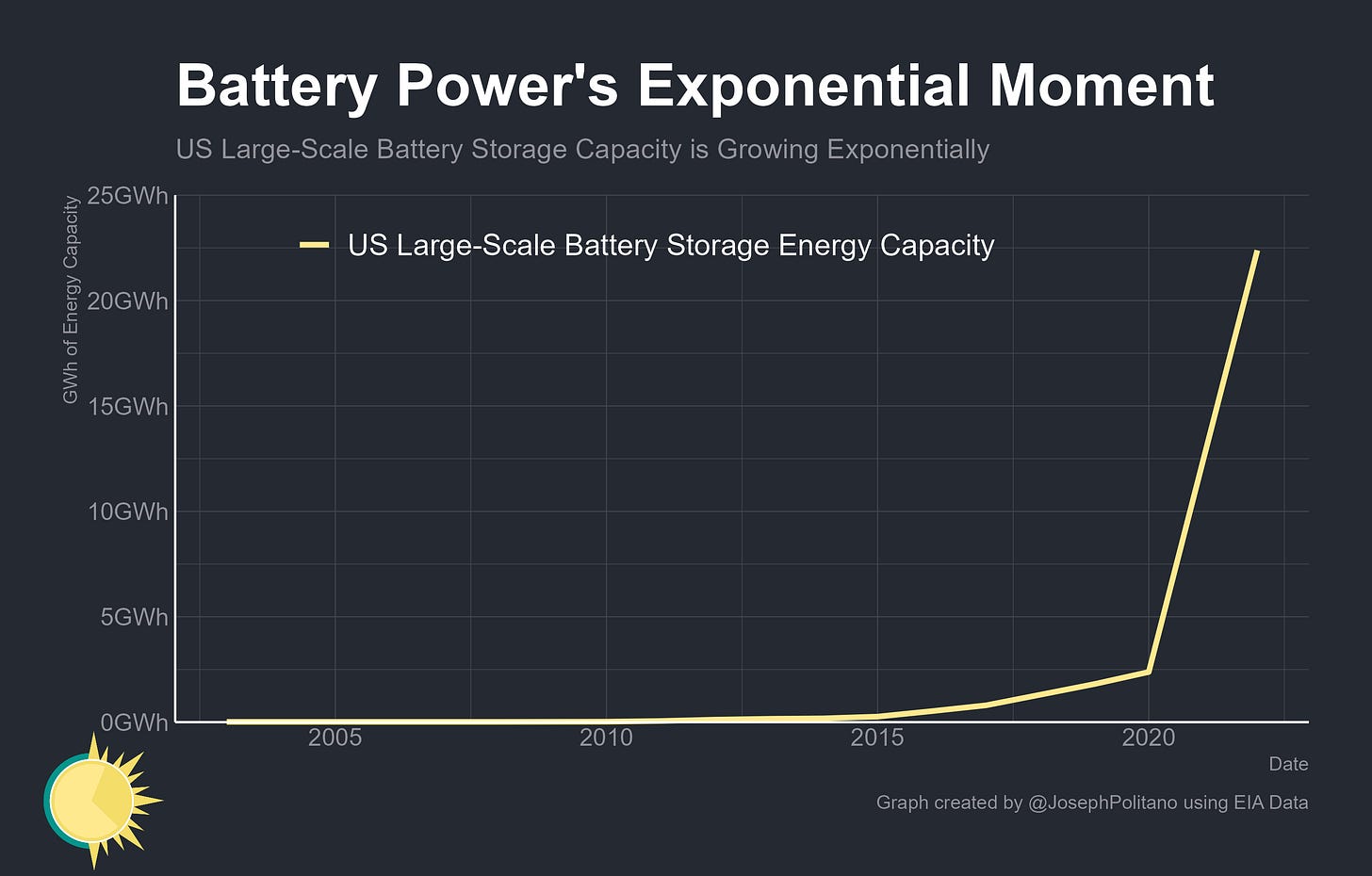

Powering those EVs is the continuous growth and advancement of rechargeable batteries, which for the first time are also being deployed at scale to supplement global power grids. The US has installed more than 20GWh of utility-scale storage batteries over the last two years, mostly to complement renewable energy in states where wind and solar are abundant. Based on planned additions, US battery power capacity—the peak amount of electricity that can be delivered at once—is projected to essentially double this year and then double again in 2024.

These cleantech goods are also radically complimentary in a way few other emergent technologies have been, with the cheap but intermittent electricity of solar power pairing exceptionally well with the flexible demand of EVs and energy storage capabilities of utility-scale batteries. Indeed, these complementary features are helping drive collective widespread global adoption—yet as it becomes clearer how important these industries will be to the future of the global economy, geopolitical competition for their control is heating up. That is especially true given that China maintains a commanding lead in batteries, EVs, and solar panels alongside a wide range of other clean energy manufacturing sectors—with most other countries forced to try and play catch-up through wide-ranging green industrial policies like America’s Inflation Reduction Act or the EU’s Green Deal Industrial Plan. The end result is a growing series of green trade wars, with all nations keen on onshoring cleantech manufacturing industries while trying to cut down foreign competitors and secure key energy supply chains.

Solar’s Time to Shine

When talking about the rise of global solar manufacturing, you're fundamentally talking about the rise of Chinese solar manufacturing—the country makes up 85% of cell manufacturing and 74% of the manufacturing that assembles those cells into modules. Earlier in the production chain, China holds even larger shares of global manufacturing capacity, with 80% of polysilicon production and 96% of production converting that polysilicon into wafers. Amidst this dominance, Chinese output of solar cells is still soaring—almost doubling since 2022 and quadrupling since 2019. To give you an idea of the scale of growth, last year the US and EU added 54GW of solar power capacity combined—and in July alone China manufactured 47GW worth of solar cells.

Of the cells assembled into panels within the country, a large number are exported and end up in Europe or elsewhere in Asia, with smaller but growing shares going to Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa. However, a large chunk of Chinese solar panels stay in China—the country made up 46% of global solar capacity additions in 2022 with its push for widespread rooftop solar drastically boosting installations in response to their energy shortages. Last year, solar delivered 4.8% of Chinese electricity, more than its share of the US power grid or the world average.

Yet countries are now making more direct efforts to curtail China's solar dominance. India, for example, has placed a large set of tariffs on imported solar products—40% on modules and 25% on cells. That's resulted in a massive reduction in imports and a nearly commensurate slowdown in solar capacity installations as domestic manufacturing struggles to keep up with the nation’s decarbonization efforts and growing electricity demand.

They are not the only ones struggling to compete with China in solar production—the US and EU, for example, are setting record highs for their domestic solar production but continue to fall well behind Chinese growth. Last year, the Energy Information Administration estimated that the US assembled only about 5GW of panels—and the agency could not even publish detailed cell production statistics because the numbers were so small they would expose proprietary individual company-level data. The early stages of subsidized domestic production are starting in both the US and EU, where solar manufacturers are eyeing rapid growth, but it remains to be seen how much hope can be turned into reality.

Winning the EV Race

On the other hand, EVs tend to be more expensive and complex than solar panels, and they come from more established companies with higher industry concentrations outside China, making them a highly sought-after target of countries with high-value-added manufacturing industries. For example, in Europe’s historic car manufacturing stronghold of Germany, quarterly production of EVs and plug-in hybrids had boomed during the pandemic, with the country manufacturing more than 300,000 total in just the first quarter of this year.

Indeed, the EU more broadly has been able to translate some of its strength in traditional car manufacturing into success in the EV world. Bloc-wide net EV exports have now exceeded €10B over the last 12 months, with Germany in particular exporting more than €20B on net.

Meanwhile, the US has gone from a net exporter to a major net importer of finished electric vehicles even after the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act. The IRA and its associated EV subsidies and tax credits have increased US production, but they have also significantly increased domestic demand—with the end result so far being a widening EV trade deficit.

Indeed, the Inflation Reduction Act’s protectionist EV policies have not had the deleterious effects European and Korean manufacturers worried about upon its passage. Quite the opposite—so far, it has turbocharged US spending on foreign-made EVs with imports from the European Union, South Korea, and Japan all steadily climbing to new highs. As pointed out by Chad Bown, this is in part thanks to the fact that non-domestically manufactured EVs can still qualify for tax credits if they are leased instead of bought, leading to a massive surge in the leasing of foreign-made EVs. In other words, the increase in federal spending has so far more than offset the effects of trade restrictions for America’s biggest EV trade partners.

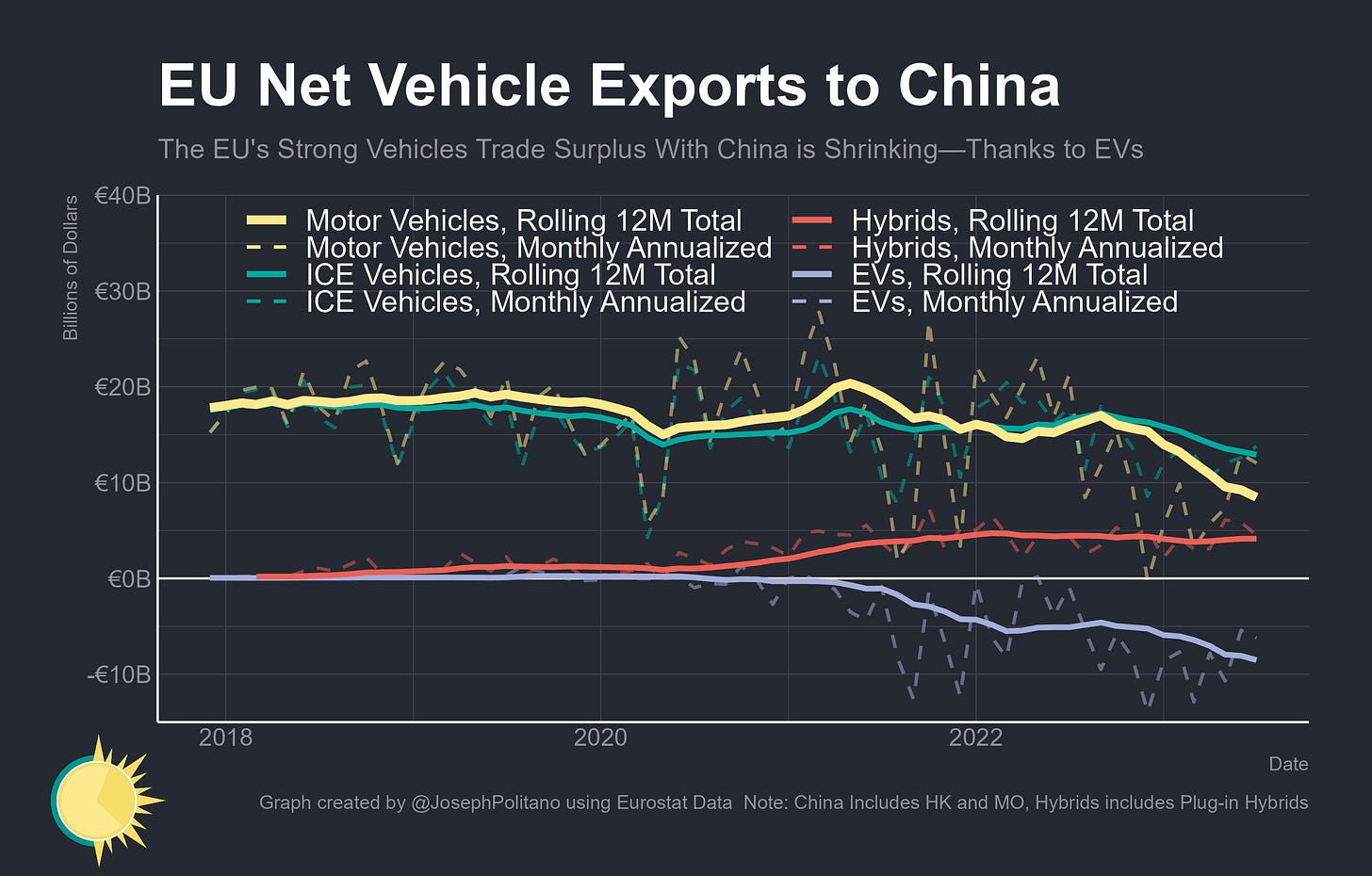

The EU’s primary EV competition still therefore comes from China, not the US, and it is here where the bloc performs more poorly. The EU used to enjoy a rather large surplus in its vehicle trade with China, but that has diminished significantly since the start of the pandemic thanks to a boom in Chinese EV exports. Over the last 12 months, the EU imported €8B more of EVs from China than it exported, heavily offsetting the large surplus in internal combustion vehicles and hybrids.

Indeed, China remains far and away the world’s largest manufacturer of electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids, assembling 800k of them in August alone—for context, the US produced roughly 830,000 vehicles per month in total last year. However, it is not so much that aggregate Chinese vehicle production has increased since pre-COVID, EVs are just making up a much larger share of the nation’s total production. By the same token, the boom in Chinese vehicle exports amidst stagnant production is a byproduct of weak Chinese consumer demand and a history of subsidies to manufacturers—hence why President of the EU Commission Ursula Von Der Leyen is opening an investigation into China’s subsidies of EV exports and is weighing tariffs and other possible responses.

The Battery Boom

The millions of new EVs on roads across the planet all require large batteries to run, as do the growing amounts of intermittent renewable energy capacity on global power grids. It’s thus not a surprise that global battery manufacturing is surging, and while the vast majority of production still occurs within China the boom has by no means been exclusively there. For example, EU industrial production of batteries and accumulators reached triple 2018 levels earlier this year before taking a recent dive.

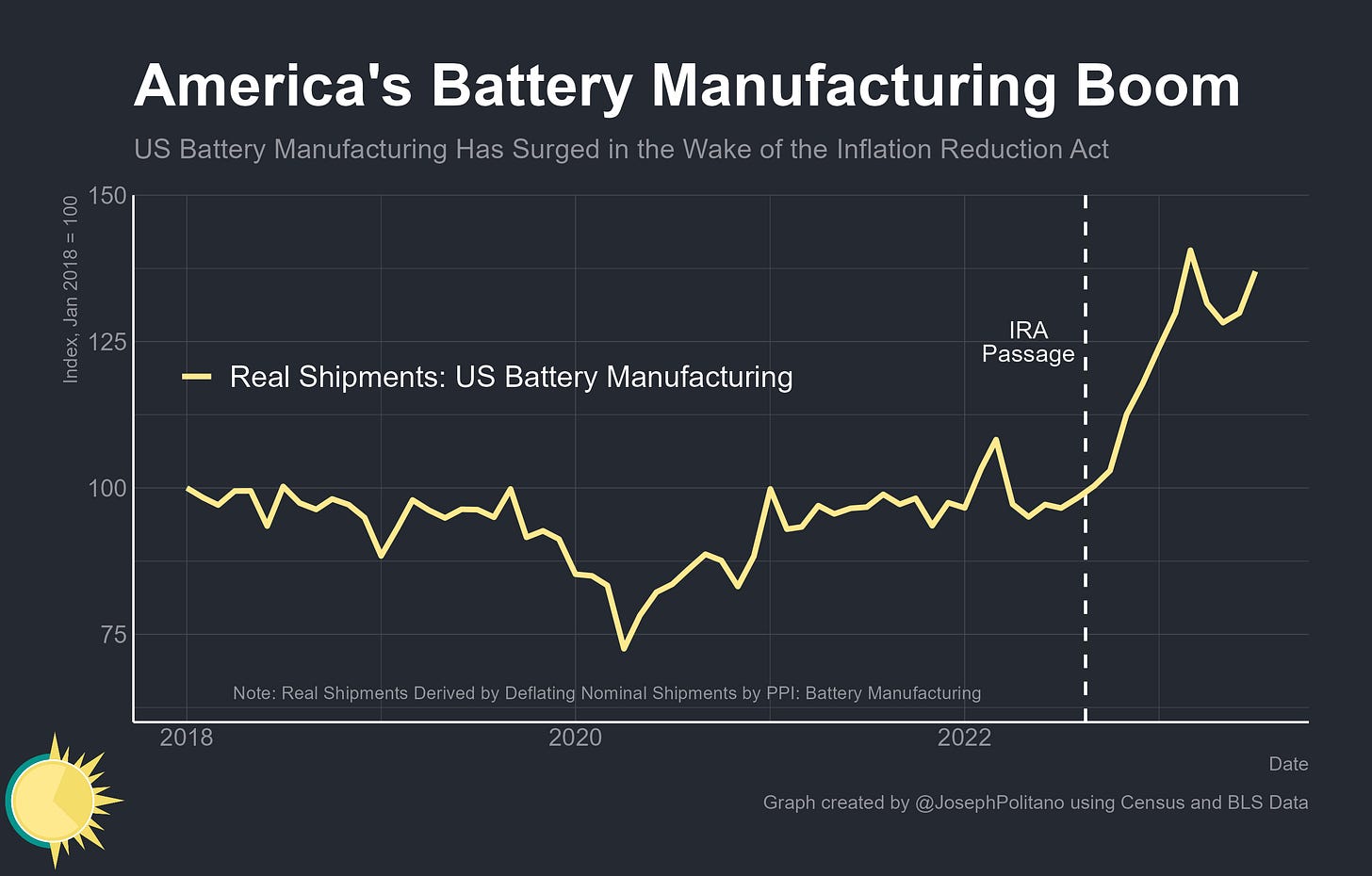

US battery production has likewise surged, especially in the wake of the Inflation Reduction Act in late 2022. The battery manufacturing data is of lower quality in the US than in the EU, and the numbers are not comparable, yet American figures still show a 35% increase in real shipments in the wake of the IRA’s passage.

Still, neither the US nor the EU are close to achieving battery manufacturing independence—and both have in fact ended up with large and growing battery trade deficits in order to support their domestic manufacturing and consumption needs. Net battery imports have been roughly $23B over the last year in both places, with the vast majority of those imported batteries coming from China.

Indeed, China remains the single-largest supplier of imported batteries in the US, with Korea, Japan, and the EU trailing far behind. Domestic US battery manufacturers’ shipments, clocking in at a roughly $16B annualized pace, are only just now exceeding America’s net imports from China alone. In other words, US production would have to more than double in order to meet all the country’s current needs without trade—under the extremely unlikely assumption there is no increase in aggregate demand.

The US data also specifically breaks out imported batteries for use in electric vehicles, which are likewise heavily dominated by China. However, there have been some substantial recent shifts as IRA battery sourcing rules come closer to going into effect—EV battery imports from China fell to nearly 0 in July, the lowest level since the early pandemic. That may be temporary—but may also be the early effects of battery sourcing rules that start going into effect in 2024 where EVs that want to remain tax-credit-eligible are prohibited from having battery components manufactured in “foreign entities of concern”—a list of nations that includes Russia, North Korea, Iran, and most importantly China. By 2025, EV-makers who want to remain eligible for the tax credits will also have to avoid critical minerals extracted or refined in China and the other “foreign entities of concern.”

That’s a good reminder that the battery trade is not just about direct manufacturers but the entire apparatus of extracting, processing, refining, manufacturing, and recycling. Two big underappreciated winners of the recent cleantech boom are Chile and Australia—major lithium exporters who have comparatively little direct involvement in solar, battery, or EV production—and the Chilean state is now making efforts to take more control of the industry. As green trade continues to get larger, so too will its geopolitics.

Conclusions

There is not a risk of overcapacity in green energy technologies—the climatological risks are weighted heavily towards doing too little, not too much, so a world in which the furor of geopolitics convinces major powers that they have to do more for the climate is a better one. Yet there are massive risks that geopolitical trade conflicts will cause the underbuilding of green energy technologies—that they will heavily reduce their efficiency and inflate costs relative to their fossil-fuel counterparts. How useful is it, when time is of the essence and resources for fighting climate change limited, to force EV manufacturers to run all their carmaking operations in triplicate so that separate production lines can satisfy EU and US subsidy rules? After all, consumers are not adopting green technologies en masse for altruistic reasons—PVs and EVs are winning because they are becoming cheaper, superior products to their dirtier counterparts. Trade conflict undermines this if all it does is replace inexpensive green imports with their higher-priced domestic counterparts and make transitioning away from dirty products more costly—especially since so many cleantech products are fixed investments that provide returns to the buyers over time.

This is compounded if green industrial trade policy regimes occur without international coordination. These policies are usually designed to wrest some control of cleantech supply chains from China, which has significant short-term costs but is understandable given economic security and geopolitical goals, but also aim to wrest back control from all other nations, which necessarily makes competition with China harder. US subsidies in the Inflation Reduction Act may have helped European, Korean, and Japanese EV manufacturers on net, but they certainly hurt them relative to the counterfactual in which subsidies did not so heavily favor domestic EVs—and they weren’t politically beloved among international partners. In many places, China’s lead is so large that it will take significant cooperation among its competitors if they are serious about catching up, which broad trade conflicts make harder.

The good news is that internecine green trade conflicts may not be as significant as they first appeared—negotiations since the IRA, though very much still ongoing, have produced a somewhat more unified anti-China trade policy front among the US, EU, and other allies. The rather large amount of government spending directed at global decarbonization efforts and cleantech reshoring is a large part of this, with cooperation being made easier when there’s less zero-sum competition. But in many ways, rich nations’ efforts to buy energy security with subsidies is the easy part—a necessary prerequisite for learning-by-doing, but not the hard work of translating investments into the kind of durable productivity growth that can keep domestic manufacturers standing on their own amidst global competition. The long-run focus must be on making domestic production more efficient, rather than just making foreign competitors artificially more costly.

Yet energy has always been an extremely fraught aspect of international trade—institutions like OPEC put fossil-fuel markets in a perpetual state of what we would otherwise consider a trade war, and Europe’s recent experience with Russian gas exposes the weaknesses of relying so heavily on energy imports from hostile autocracies. Despite everything, the global green energy trade regime remains freer than its competition—which is partly why it’s growing so exponentially.

The chart of panel exports to India screams out that BRICS don't exist

Love the details on Europe! The data show that the EU has actually done quire a lot on EV and battery manufacturing, with more in the pipeline.

As usual, it doesn't do that with a big bang, but it has worked to build up these industries for some years now. Personally, I think Chinese automakers will capture some of the lower-price segments of the car market and European automakers will move further upmarket.

Whether the US or the EU can catch up on utility batters and particularly PV - and if it is worth to do it - remains to be seen.