The Housing Credit Crunch

How the US Housing Market is Surviving the Rapid Increase in Mortgage Rates Over the Last Year

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 28,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

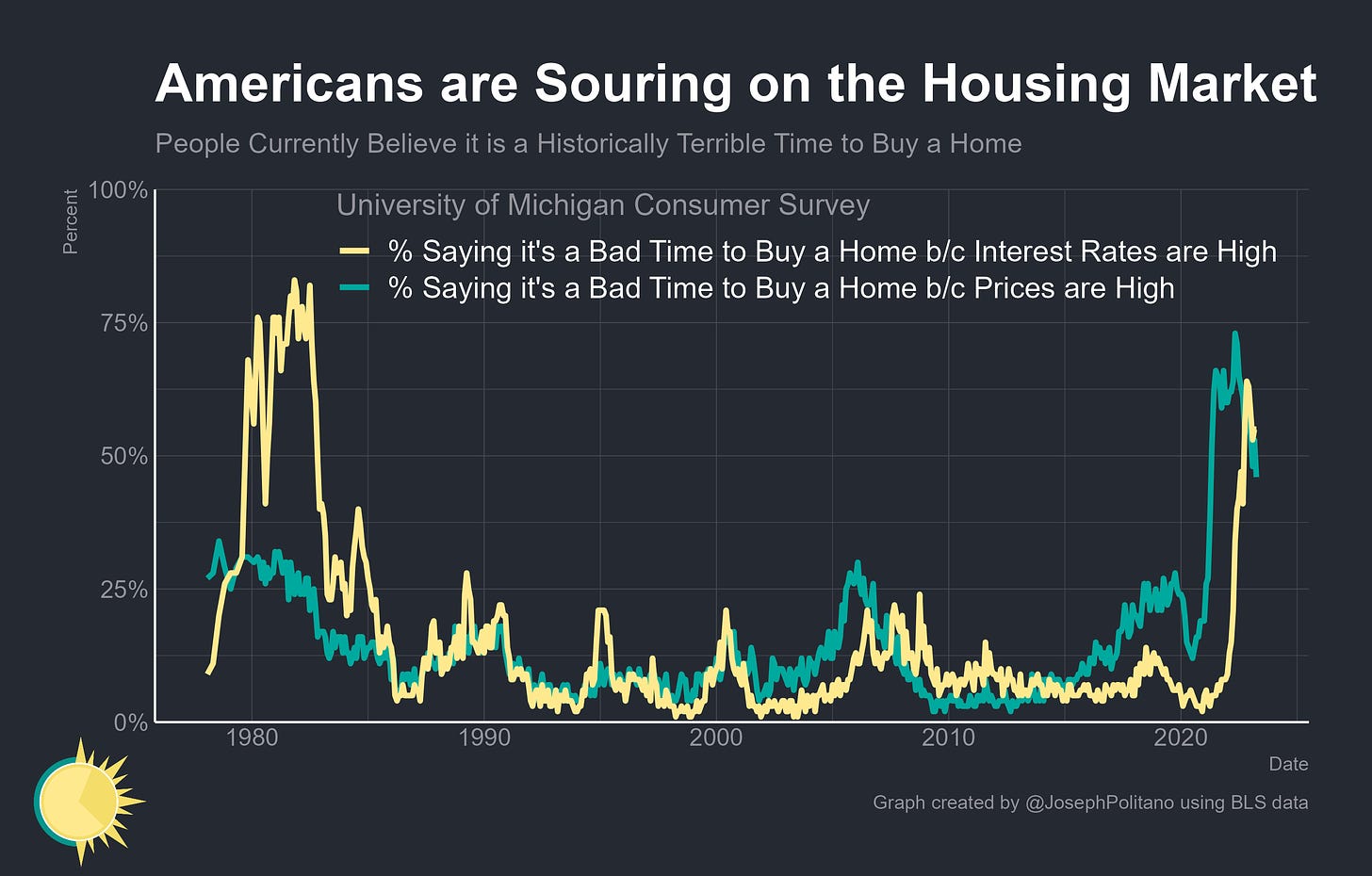

If you ask Americans whether now’s a good time to buy a house they’ll unequivocally tell you “NO”—three-quarters of respondents to the University of Michigan’s consumer survey currently say it’s a bad time to buy, citing both elevated prices and higher interest rates. Buyer sentiment is worse than during the Great Recession, with the only comparable period being the Volcker Shock of the late 1970s and early 1980s—fitting, given that the rapid increase in mortgage rates since the start of 2022 has caused a massive credit crunch that the housing market is still adjusting to.

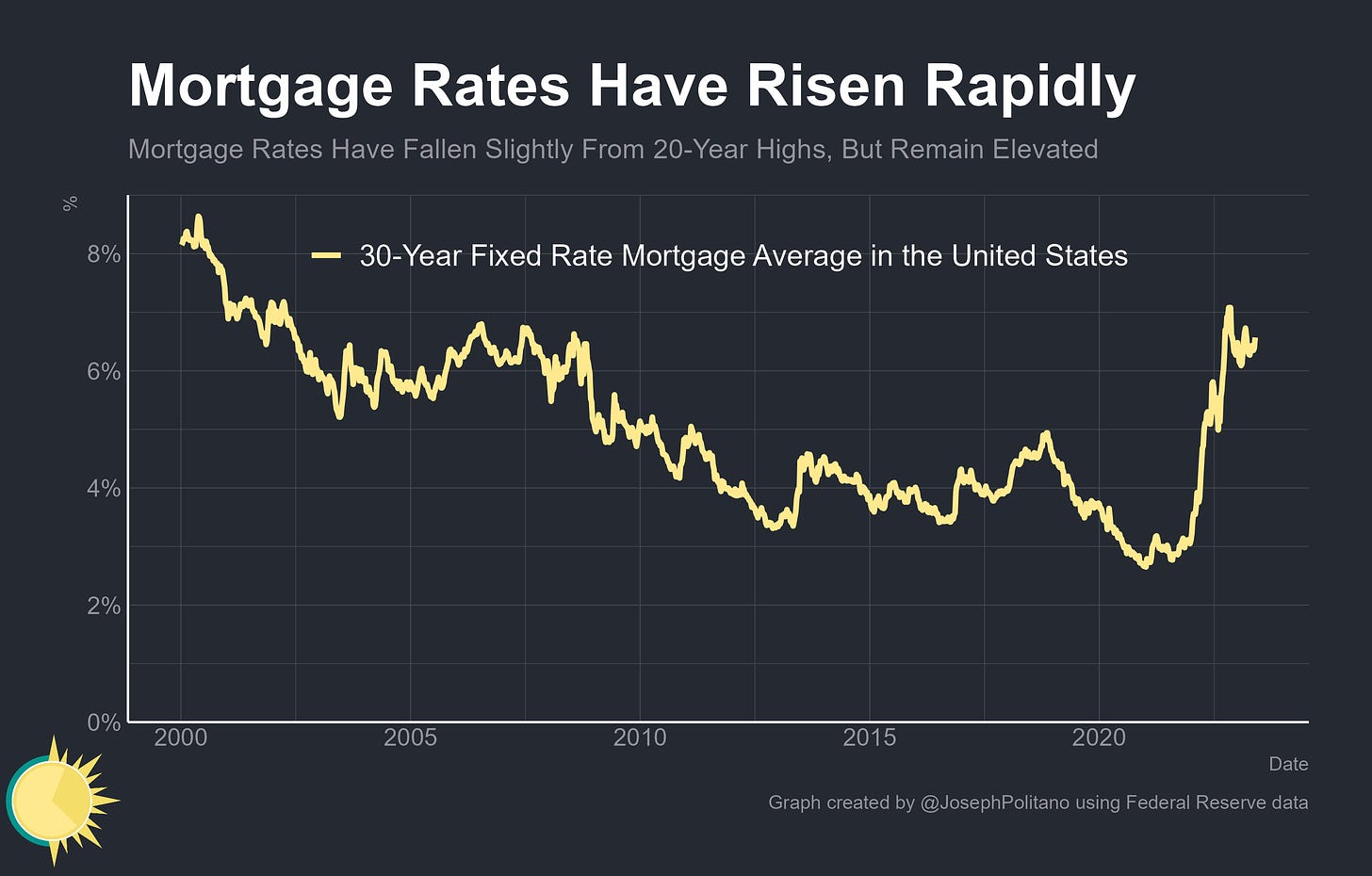

30-year fixed mortgage rates skyrocketed when the Federal Reserve began tightening monetary policy as part of their campaign against inflation, hitting levels not seen since before the Great Recession and occasionally glancing into 7%+ territory. As a result, existing home sales and new inventory have both plunged more than 20% over the last year, residential fixed investment is at a 5-year low, real estate prices have fallen measurably for the first time in a decade, and single-family housing starts have settled well below pre-pandemic levels.

Yet what’s arguably been most remarkable has been the relative resilience of the housing market—nationwide prices haven’t collapsed despite the relatively enormous increase in rates, employment in housing-related sectors hasn’t fallen, and sentiment among homebuilders is rebounding. It’s not all roses—the market is partially being cushioned by the dwindling backlog of projects started during the pandemic, and recent bank failures will likely drive further credit tightening from institutions with big losses on their commercial real estate portfolios—but the housing market is holding up so far amidst a historic credit crunch.

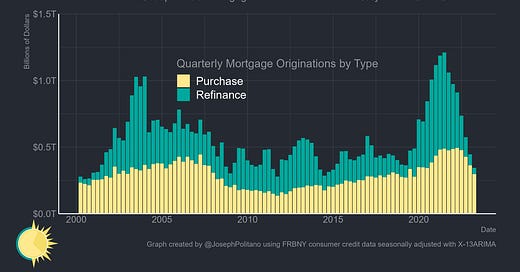

The Pandemic Mortgage Boom is Over

The early pandemic saw one of the largest mortgage booms in American history—with more than $1T of mortgages being originated every quarter at the peak. The rapid reduction in interest rates at the onset of the recession and the simultaneous permanent surge in housing demand as COVID changed living patterns meant that millions of existing homeowners could easily refinance for lower interest rates or to extract home equity. Nationwide home appreciation and a boom in construction also sent purchase mortgage originations to new record highs.

The Pandemic Mortgage Boom ended just as quickly as it began, however—the rapid rise in interest rates over the last year has brought refinance activity to the lowest levels in decades. The vast, vast majority of homeowners with existing mortgages have lower rates than what is being offered today, so few of them can gain much by refinancing. That bygone early-pandemic refinance activity facilitated extra household consumption, particularly of home improvements and durable goods, which is now slowing as the downstream effects of tighter policy take hold. Purchase activity, too, has slowed—though importantly those originations have only returned to pre-pandemic levels despite the surge in rates.

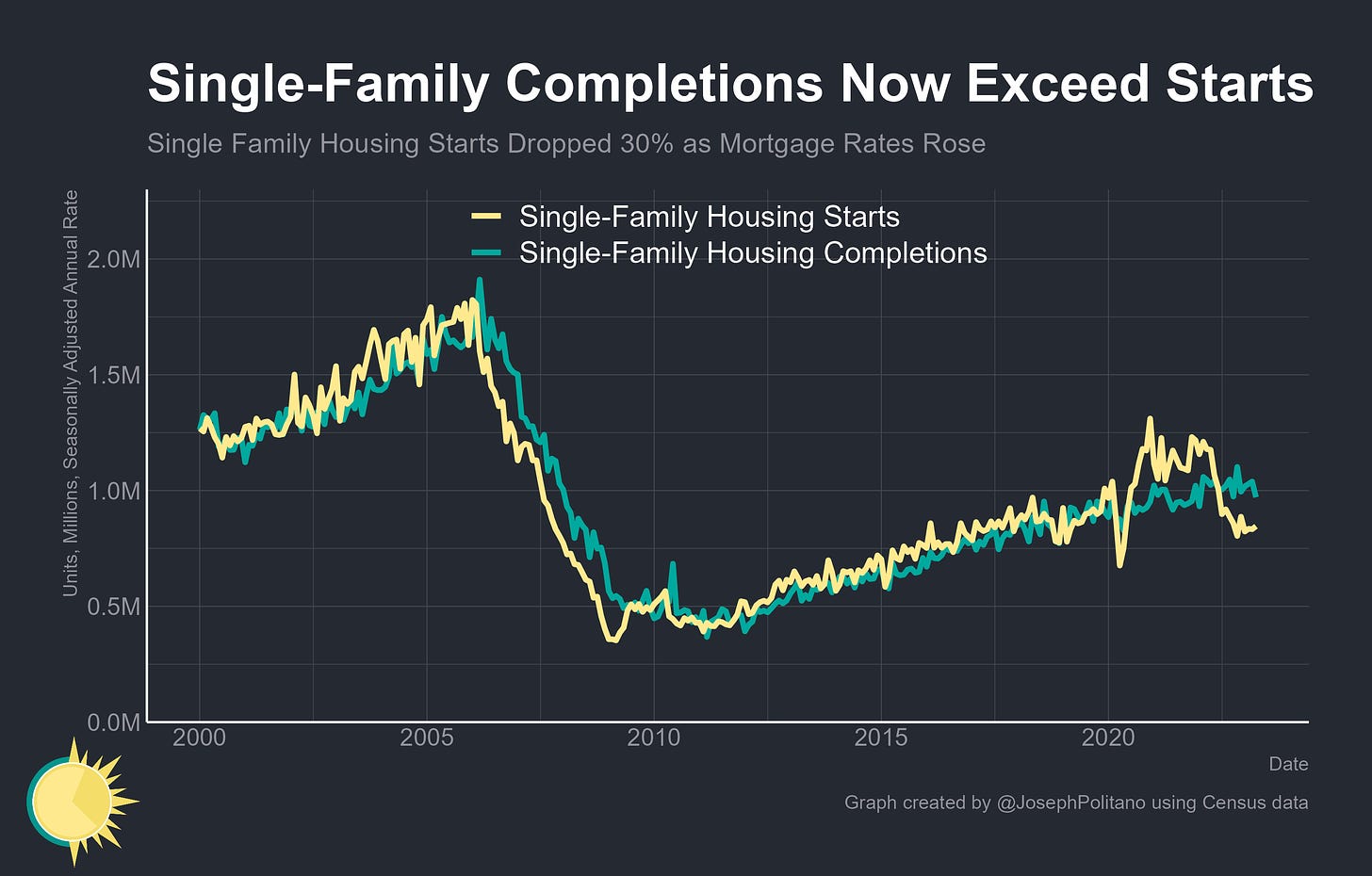

In the early pandemic, the Pandemic Mortgage Boom helped single-family housing starts skyrocket. With newly lowered interest rates, consumers could readily afford bigger sticker prices for the same monthly payment. Housing was one of the few major purchases consumers could funnel their new “excess savings” into, and with the rise of remote work families could move to more construction-friendly areas where housing was relatively affordable. The constraint rapidly became construction capacity—physical inputs like wood were in famously short supply, as were labor and other materials. Prices skyrocketed, with the Census Bureau’s index of single-family construction costs rising 40% from the start of 2020 to the peak in late 2022. With not enough to go around, construction times lengthened and the number of single-family homes started vastly exceeded the number actually completed. That is until mortgage rates started rising, at which point single-family starts plunged back to pre-pandemic levels and fell significantly below completions.

The net result is that the surge in housing starts at the start of the pandemic essentially created a buffer that has cushioned the impact of higher rates on residential construction employment. The backlog of homes under construction and incomplete renovation projects means that residential building employment has not fallen back to 2019 levels even as single-family housing starts have. That’s important in particular because single-family housing construction is a much bigger force in the labor market than multi-family construction. There are nearly an order of magnitude more workers in both single-family construction and residential remodeling than in multi-family construction, despite the fact that multi-family construction makes up 40% of the new housing starts in the US. Indeed, the relative weakness in single-family construction employment is a large part of the reason aggregate construction employment has stagnated even as multi-family starts approach 40-year highs.

The credit crunch has also reshaped American home prices, with the main dynamics being threefold. First, nationwide home values are declining slightly—but noticeably—for the first time since the 2008 recession. Second, that decline has been regionally concentrated in the Western US—all of the major metro areas with substantial price declines in the Zillow Home Value Index are in the West Census region, with California hit particularly hard. Thirdly, changes in lifestyle, work preferences, and migration patterns have caused a “donut” pattern to emerge in many metro areas, with prices in the expensive urban cores declining while prices in the surrounding suburbs and exurbs are holding up better. In other words, home price declines have thus far manifested as a correction to the expensive, supply-constrained markets that boomed most in the preceding decade, not as broad declines across the entire nation. Those patterns have made the impact of this housing credit crunch much more disparate—and complex—than in prior cycles.

A Deeper Look at Housing Prices

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.