Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 7,700 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

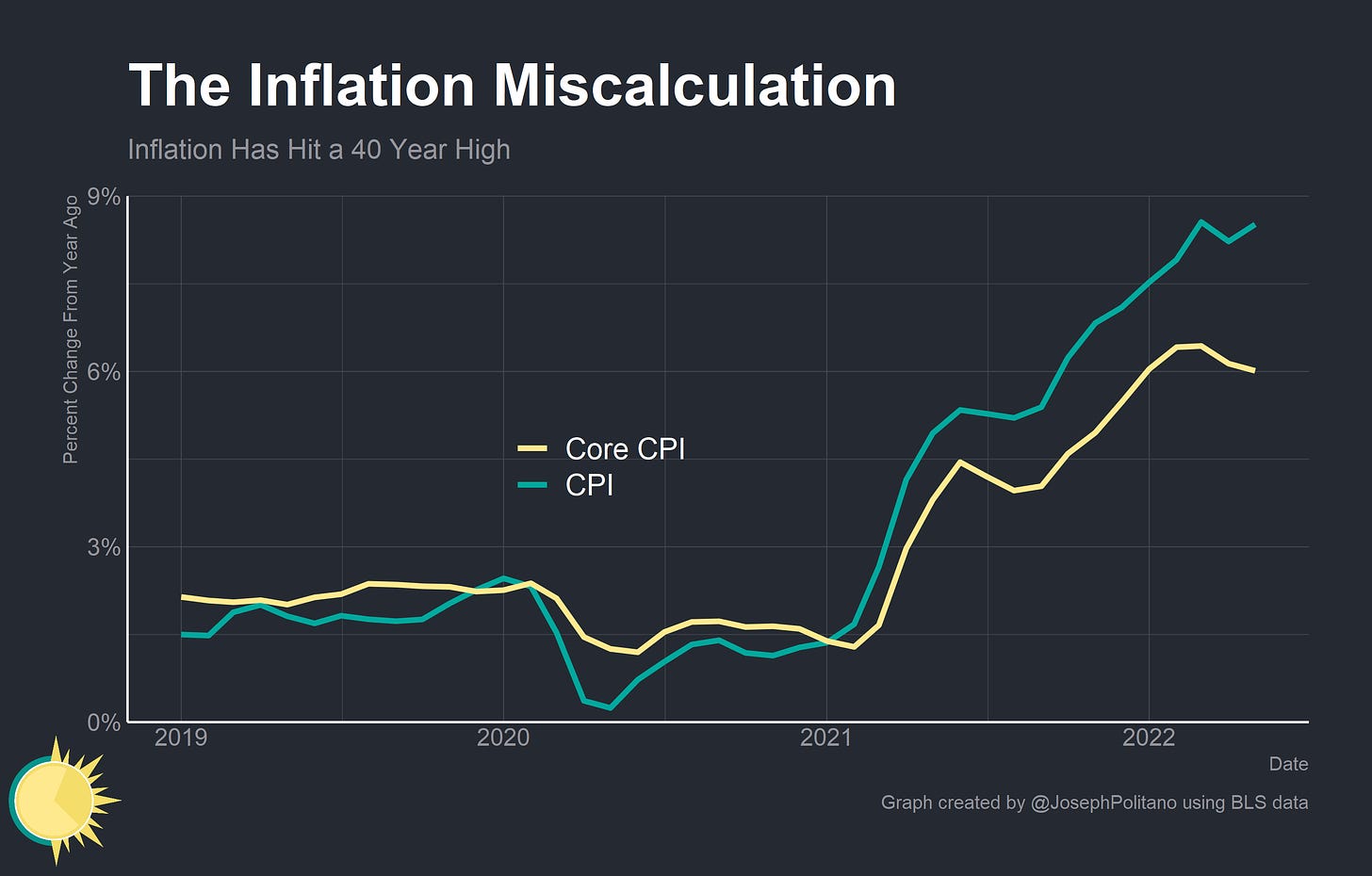

Headline annual inflation is currently sitting at 8.6% as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI)—the highest level in more than 40 years. Just over a year ago academics, policymakers, and pundits (including myself!) were calling the then-5% inflation “transitory”; a theory that has since earned its due share of mockery in the wake of continued price accelerations. The general argument at the time was that 2021’s price increases were mostly catch-up from the low inflation experienced in 2020 alongside a bunch of idiosyncratic factors (a chip shortage lowering car production, homebound consumers spending a record share of income on goods, and the ongoing health effects of the pandemic) that would dissipate without further action from monetary or fiscal policymakers. Instead inflation only got larger, longer, and more broad-based. How did so many people get the forecast wrong?

I’ve given a lot of thought to my own forecasting failure—and the similar forecasting failures of central banks, elected leaders, and academics—over the last few months. I’ve found it especially important in light of what I view as the increasing risk of the opposite forecasting error where central banks tighten aggressively into a slowdown, causing an undue recession. I’ve settled on a non-exhaustive list of factors that upended the transitory inflation narrative—some of which should have been forecasted, some of which couldn’t have been—that fit into three main themes:

The Recovery Was Faster Than Expected

There Was A Genuine Demand Overshoot

Major Supply Disruptions Continued

1. The Recovery Was Faster Than Expected

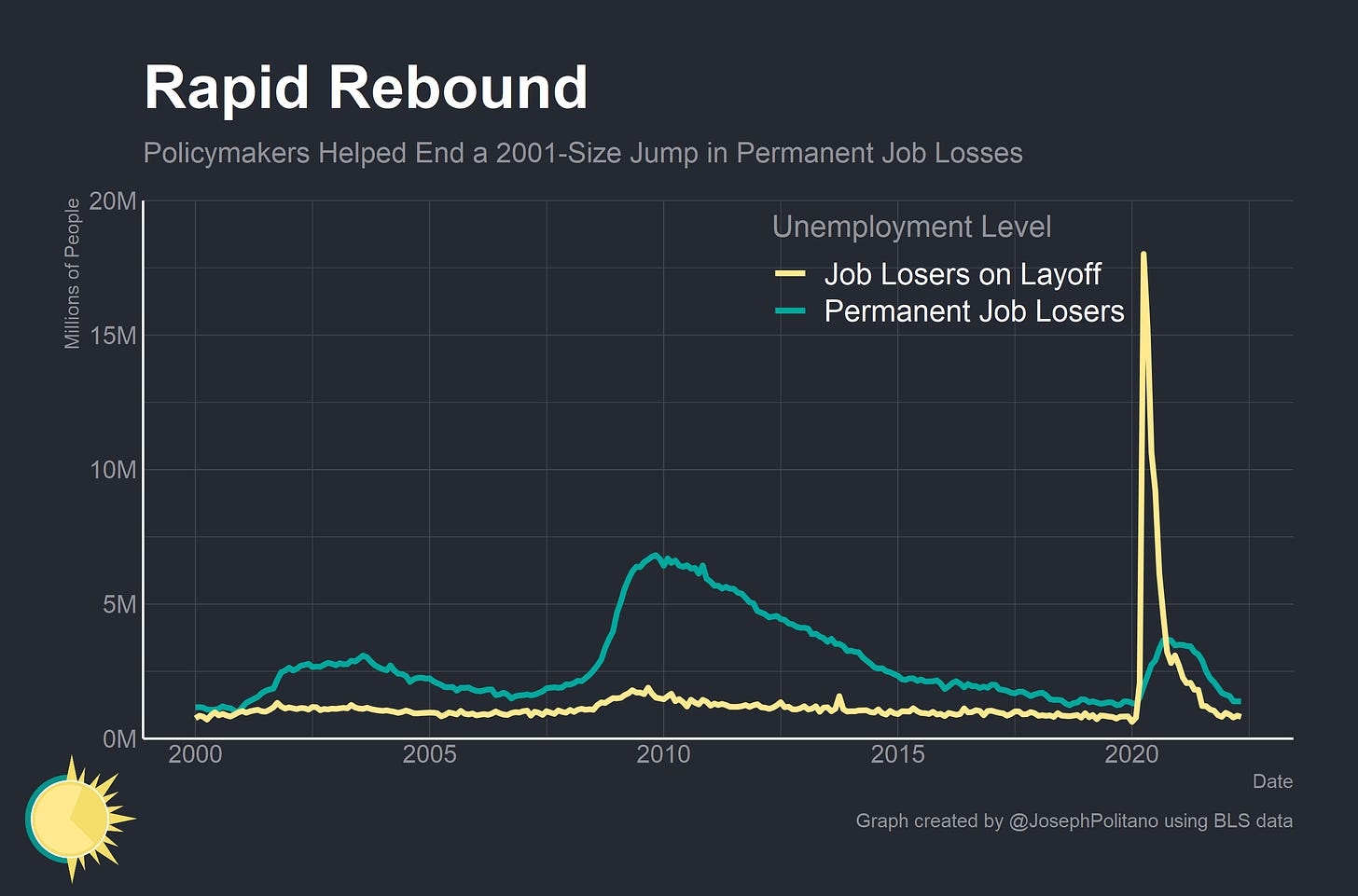

The vast majority of workers who were unemployed at the start of the pandemic were temporary layoffs who likely regained their old jobs relatively quickly. But the conventional wisdom leans too far in this direction—there was also an extremely large number of people who permanently lost their jobs and remained unemployed for a long time. The key word there is “was”, because between May 2021 and May 2022, the number of unemployed people who had permanently lost their jobs decreased by 2 million—a larger decrease than in the entire recovery from the 2001 recession. It took from 2014-2018 to reproduce a similar decline in permanent unemployment during the last recession.

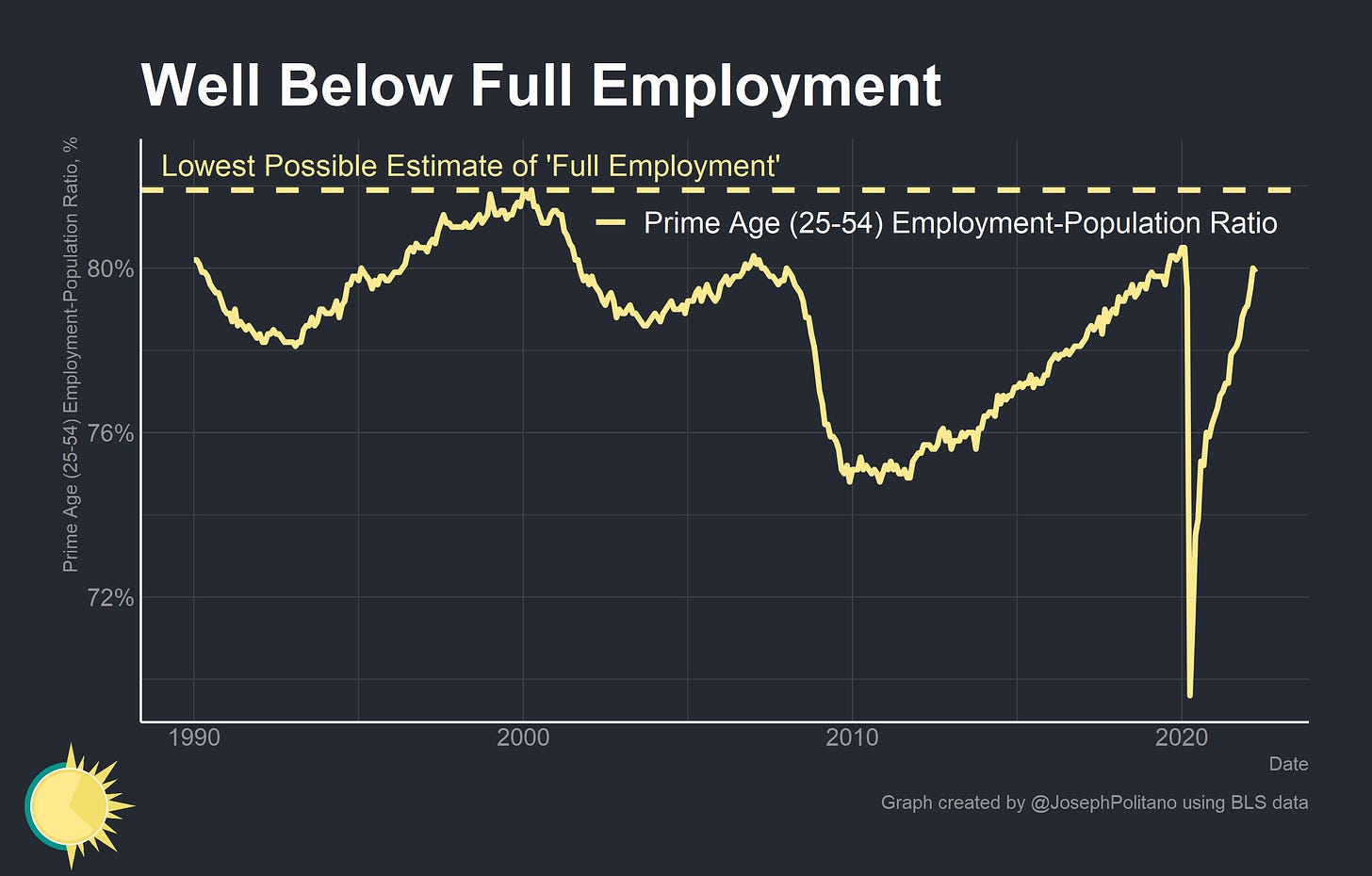

In May of 2021 the prime-age employment population ratio—which represents the share of working age adults with jobs—stood at just over 77%, about the same as in early 2015. But in 2015 raising rates above the zero lower bound caused a mini-recession and forced the Fed to be much more cautious in future rate hikes. Using the same employment and unemployment rates to forecast inflation using labor market slack in 2021 proved wrong both because the labor market recovery was much faster than expected and because many of the fundamental drivers of inflation came from outside the labor market. But in general, an underestimation of the fundamental strength of the labor market, consumption, production, and household balance sheets in late 2021 led a lot of policymakers (especially monetary policymakers) to erroneously conclude that the economy couldn’t yet handle any tightening measures to combat inflation.

2. There Was a Genuine Demand Overshoot

The textbook story of inflation is “too much money chasing too few goods.” A lot of analyses take this idea extremely reductively and presume a direct relationship between money supply growth and inflation where one doesn’t exist (structural forces and new financial plumbing have weakened the already-tenuous relationship between money supply and inflation that existed pre-2008; countries like Japan that have seen large growth in money supply over the last few years without commensurate inflation). People miss the “chasing” element constantly—it is income and spending growth more than money supply growth that determines long run inflation. But in countries with a track record of low inflation and stable income growth it can also become too easy to ascribe all shifts in inflation to supply issues or idiosyncrasies; few people would doubt that Argentina’s 50% annual inflation is caused by monetary policy but were hesitant to blame spending growth for 5% inflation in the US.

Indeed, consumer spending was at the upper bounds of the pre-COVID trend back in mid-2021 and has significantly exceeded the trend since then. This is where I feel it is appropriate to ascribe some more significant blame on myself and others’ forecasts; it should have been more obvious that consumers were going to spend down a large chunk of the “excess savings” that they accumulated in the early pandemic and that the cumulative effect of all that excess spending would generate inflation. Personal income has even overshot the pre-pandemic trend—and that is despite being pulled down by record capital gains taxes.

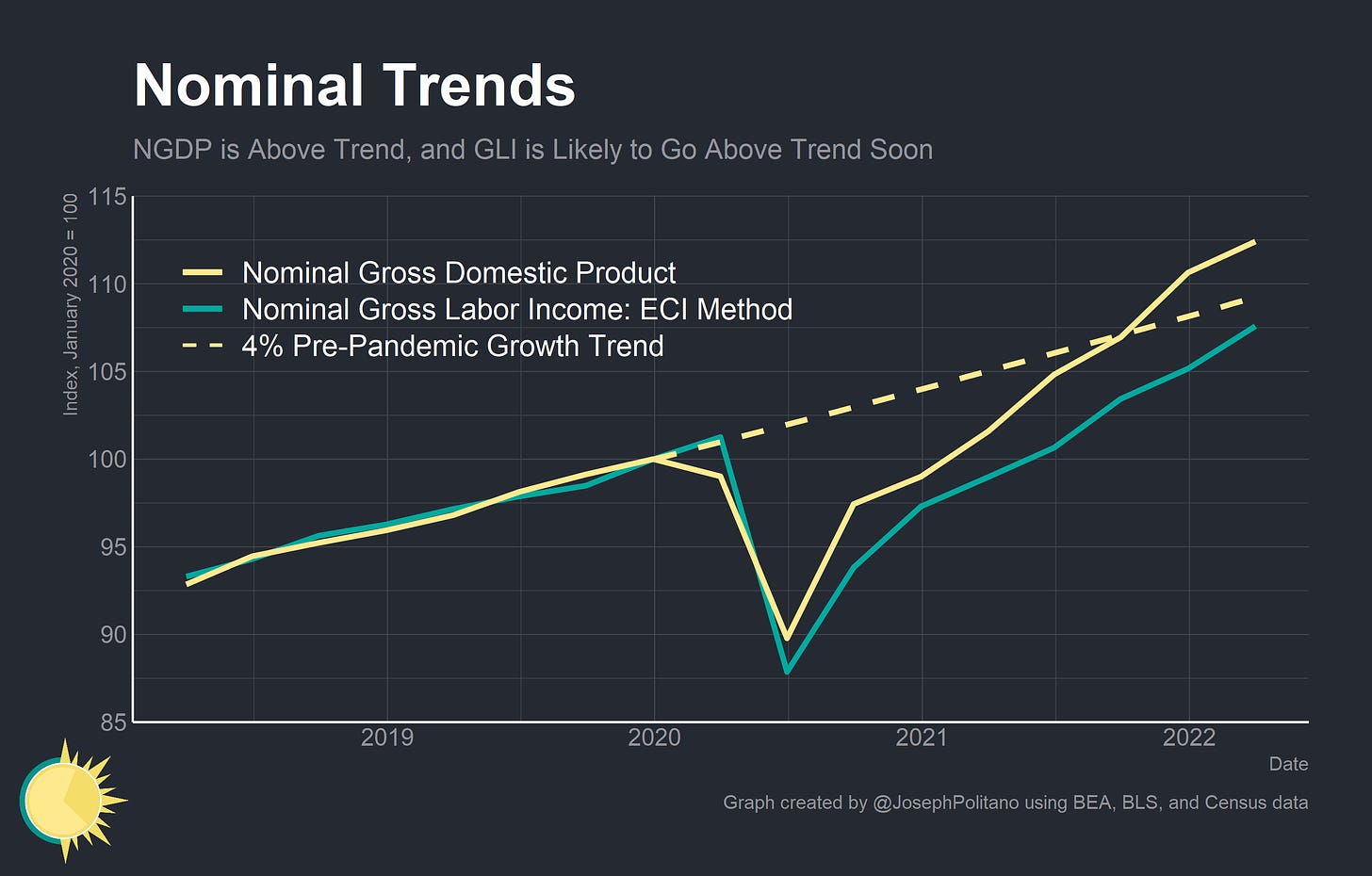

Nominal Gross Domestic Product (NGDP), which measures aggregate spending in the economy, has also overshot its pre-COVID trend while Nominal Gross Labor Income (NGLI), which measures the sum total of workers’ incomes, looks set to do the same in the second quarter of this year. Indeed, other measurements of NGLI (derived from BLS or BEA data) have already significantly overshot the pre-pandemic trend. All of that is indicative of the kind of monetary-policy-driven broad-based inflation we are currently experiencing.

The simplest way to see this in action is to look at services prices. In normal times, services prices (about half of which are housing) will be the biggest positive contributor to inflation, as services costs tend to grow in direct proportion to wages. Meanwhile durable goods prices tend to be the biggest negative contributor to inflation as manufacturing processes improve over time, and nondurable prices tend to fluctuate along a slowly increasing long-run trend. The initial shock the pandemic inverted all of that; services price growth slowed while prices for goods skyrocketed. But over the last year even services prices have overshot their pre-pandemic trend, indicating how broad-based and demand-driven inflation has become.

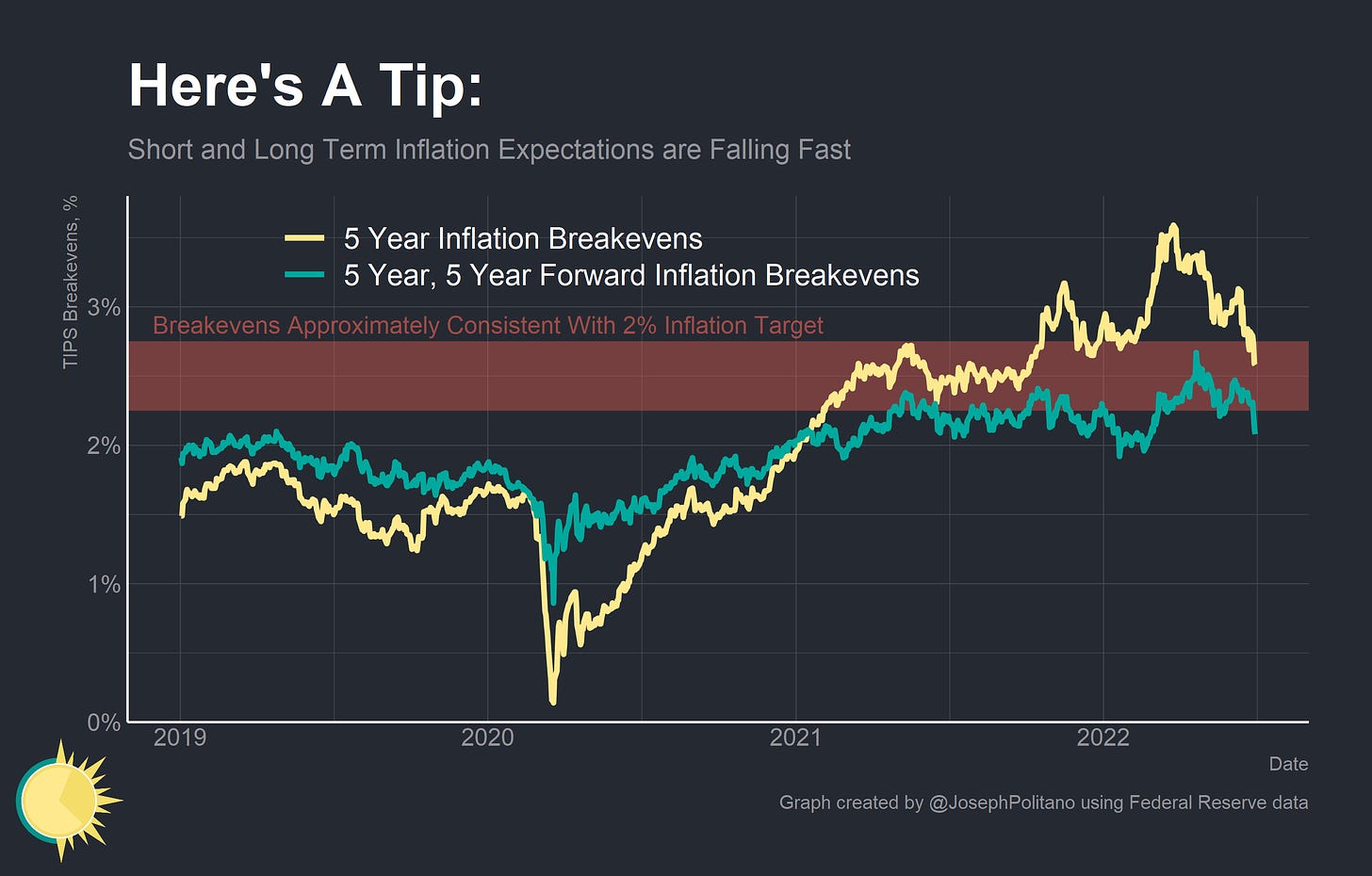

To give some credit to past predictions even market-based measures of inflation expectations were not indicating significant long-run inflation risk by mid-2021. That wouldn’t come until later 2021 and early 2022, at which point policymakers acted swiftly to re-constrain inflation expectations.

However, some amount of the blame ought to be ascribed to policymakers and pundits “fighting the last war.” For the last 10 years high-income nations have dealt with a demand undershoot where abundant excess physical capacity and underutilization of labor were the norm. Fiscal and monetary authorities in the US were caught off guard when thrown into a situation in which physical capacity was in short supply and labor utilization was relatively high.

3. Supply Disruptions Continued

Still, that doesn’t make for a satisfactory conclusion. Inflation is extremely high across the world—7.7% in Canada, 7.9% in Germany, 5.5% in Australia, 5.4% in South Korea—did every major country on earth really make the same macroeconomic policy errors? Sure, inflation is much more concentrated in energy within the EU than it is in the US and countries like Japan have managed to keep core inflation low, but the bigger explanation is that global COVID-induced supply chain disruptions have persisted and even intensified over the last year. In retrospect, the transitory inflation narrative rested too much on optimistic projections of supply chain renormalization and could not predict the food and energy shocks caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

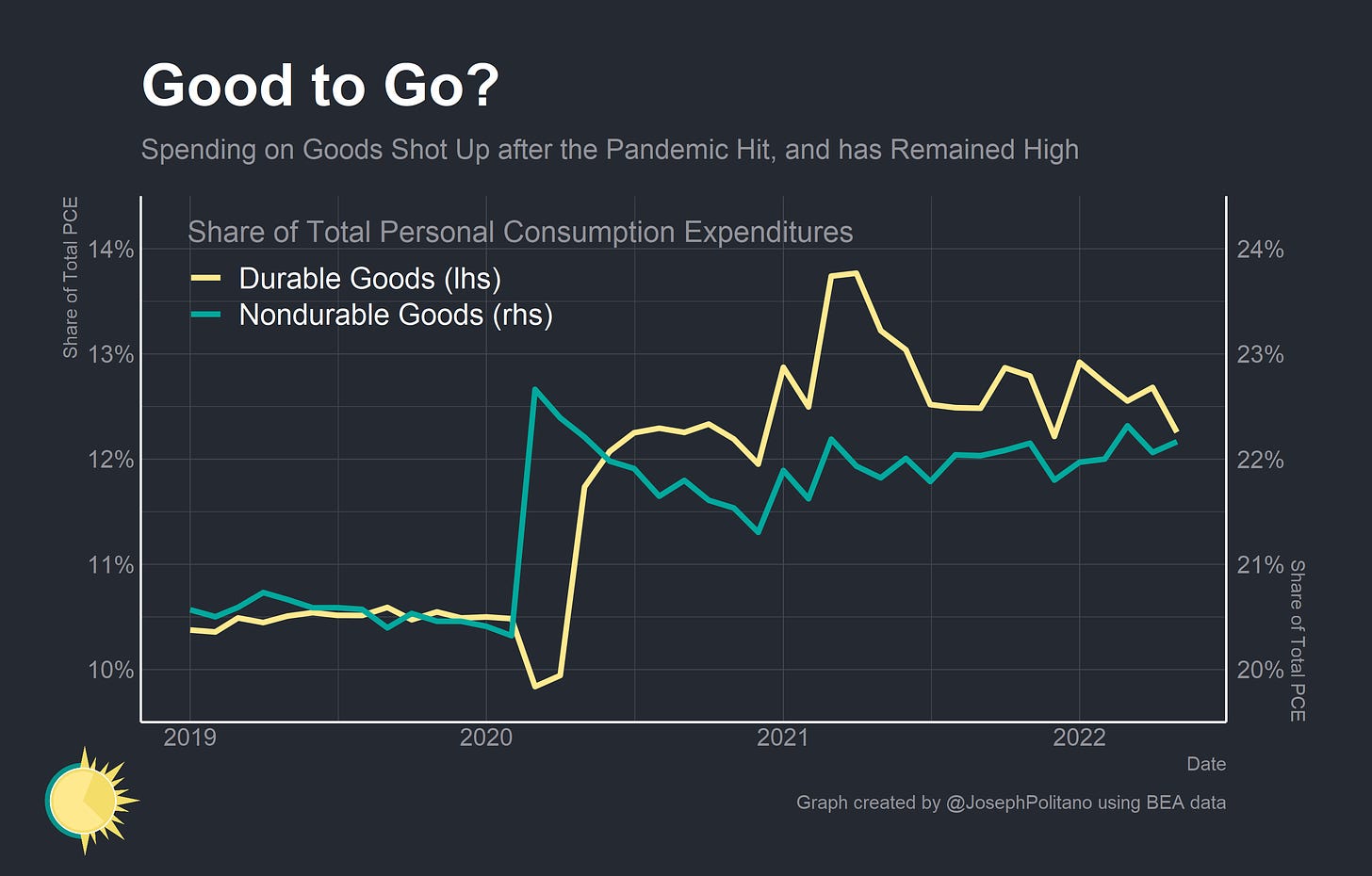

For example, one of the key drivers of the inflationary impulse in 2021 was the record goods spending of homebound consumers across the globe. As vaccines became more widely distributed, consumption was supposed to renormalize—people would want to buy less new furniture and more concert tickets—a change that would be welcome considering how much labor demand in high-income nations is dependent on services production and how dire the shortage of physical capacity for goods production was. Instead, more than two years into the pandemic and more than a year and a half after the initial vaccine rollout, Americans are still spending a disproportionate amount of money on goods—putting further strain on supply chains.

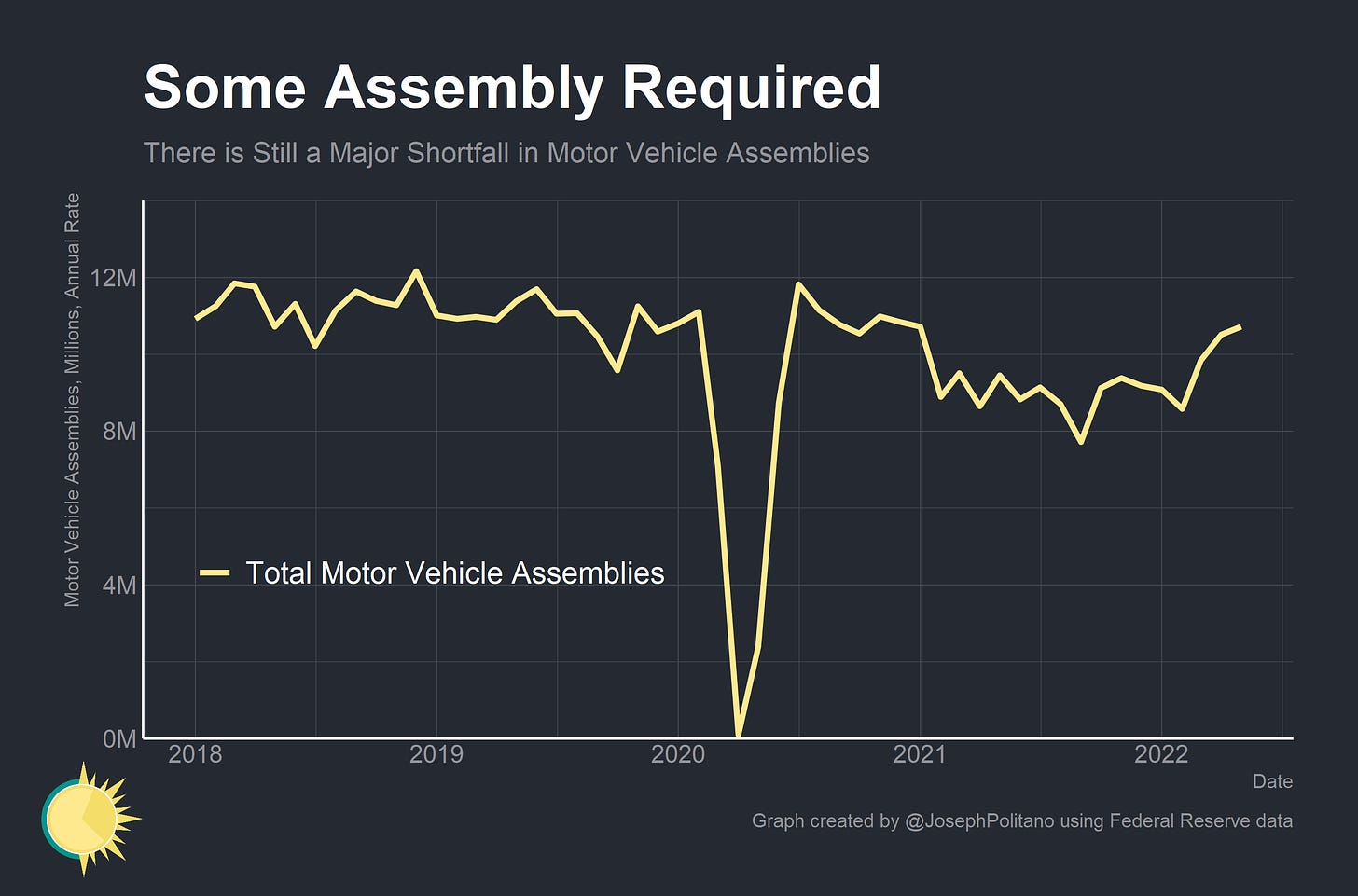

Production of key goods in the United States also did not improve much as time went on. Automobiles were the center of attention this time last year after a 50% rise in used vehicle prices added 2% to CPI alone. The end of the semiconductor shortage was supposed to allow new car production to catch up and bring used car prices down—but here we are more than a year later and domestic vehicle output still remains below 2019 averages. The cumulative production shortfall has only grown, keeping used car prices elevated and pushing new vehicle prices up 15%.

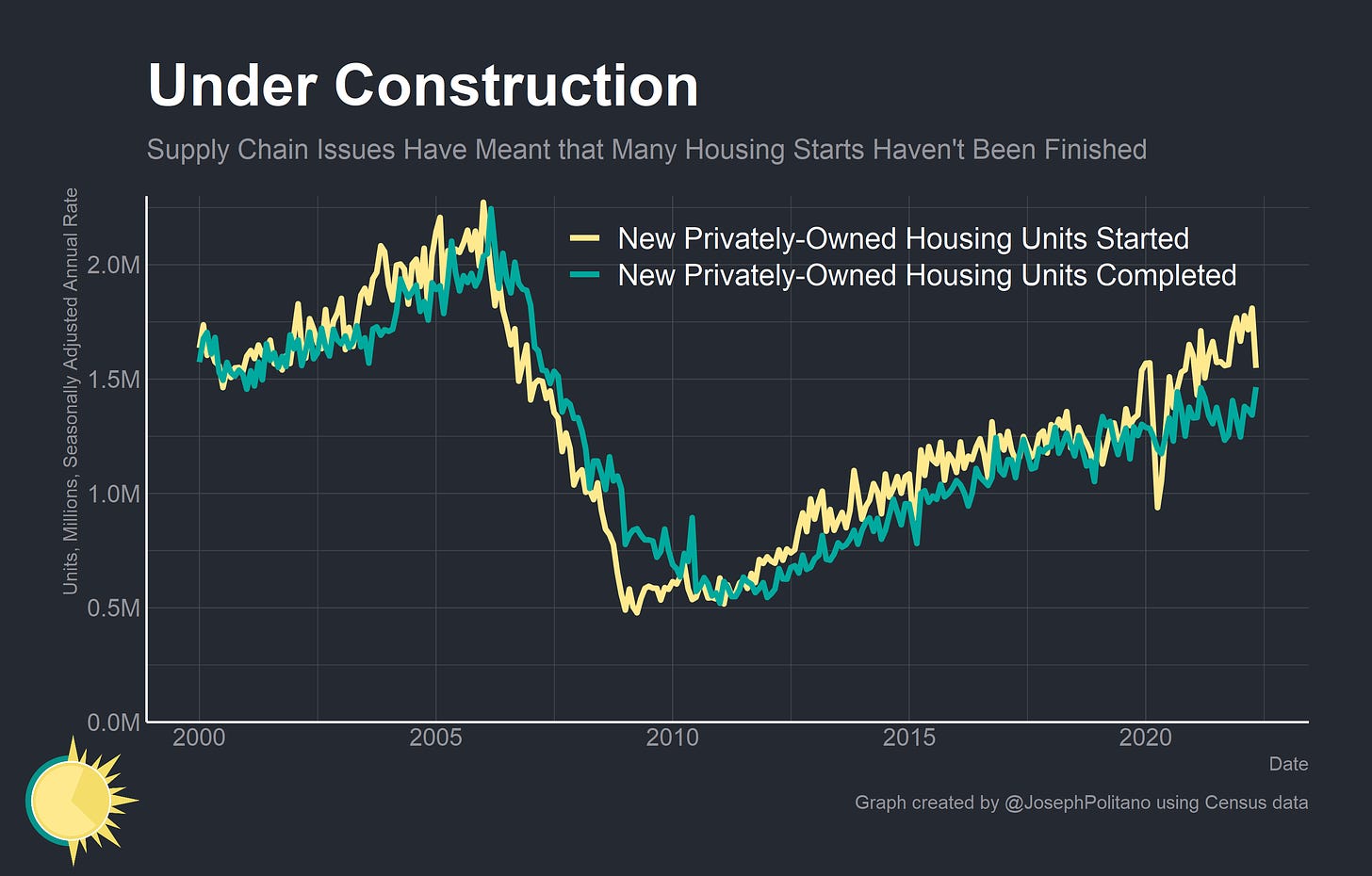

Or take housing—despite record-high demand, supply chain pressures have slowed down construction times, prevented started projects from finishing, and prevented permitted projects from starting. The end result is that the actual number of new housing units coming online each month has barely moved throughout the last two years, putting significant upward strain on housing prices—which make up 1/3 of the CPI.

Then there is the ongoing energy crisis. Global oil markets were already in a precarious position before the Russian invasion of Ukraine—and now there is an acute shortage of both crude oil and refinery capacity that is pushing gas prices up. Or take natural gas, where the dearth of Russian exports is driving up prices in the EU and by extension the US. Or food prices, which have skyrocketed in part due to natural-gas-related nitrogen fertilizer shortages and in part due to disruption of critical crop imports from warring nations. All of these represented significant global supply shocks that were extremely difficult to forecast ahead of time, and you could fill a whole encyclopedia with the intricacies of the supply chain disruptions across the globe.

Conclusions

We understand better how little we understand inflation

Jerome Powell

Economists often like to imagine the world as fitting neatly into the set of models and calculations—they’re the kind of people who look for the box scores instead of highlights, and sometimes they need to get egg on their faces before they update their priors. One of the primary lessons of the last two years should be that outside factors—like pandemics and wars—can drive economic conditions in ways that don’t fit neatly into models.

Still, I don’t want to absolve what were in many ways fundamentally wrong decisions and predictions—my interpretation of team transitory’s position was about whether tighter policy was needed to constrain inflation, and I think it has been more than proven that some amount of rate increases were necessary. But in a similar vein to how the Federal Reserve ignored some of the signs of of elevated inflation last year they are now ignoring some of the signs of elevated recession risks this year. Corporate credit spreads are at the highest levels since the initial COVID crisis and higher than at any point between 2017-2019, employment rate growth has stalled over the last three months, futures markets are pricing in significant rate cuts in 2023 and 2024, and manufacturing PMIs are showing extremely weak output growth or outright contraction. Hiking aggressively into an energy shock has an especially bad track record of success in the US.

On the other side, there are signs that short term inflation may be rolling over—consumers’ excess savings are being spent down rapidly, commodity prices are dropping, oil prices are down from their highs, 5-year inflation expectations have shrunk a full percent from their March highs, aggregate labor income growth has slowed, the federal government is nearly running a budget surplus, and real rates have increased significantly. The crisis could rapidly roll over from one in which spending is too high into one where spending is too low, and we should not ignore the continued signs of a worsening economy.

Great work! I like the balanced discussion: everyone who dunks on central bankers and forecasters for having gotten it so wrong just proves how little he knows about the complexity of it all.

Worse case would be that the Fed tightening spills over internationally with a stronger USD that kills supply faster than domestic demand. It’d keep inflation high and continued tightening.