The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

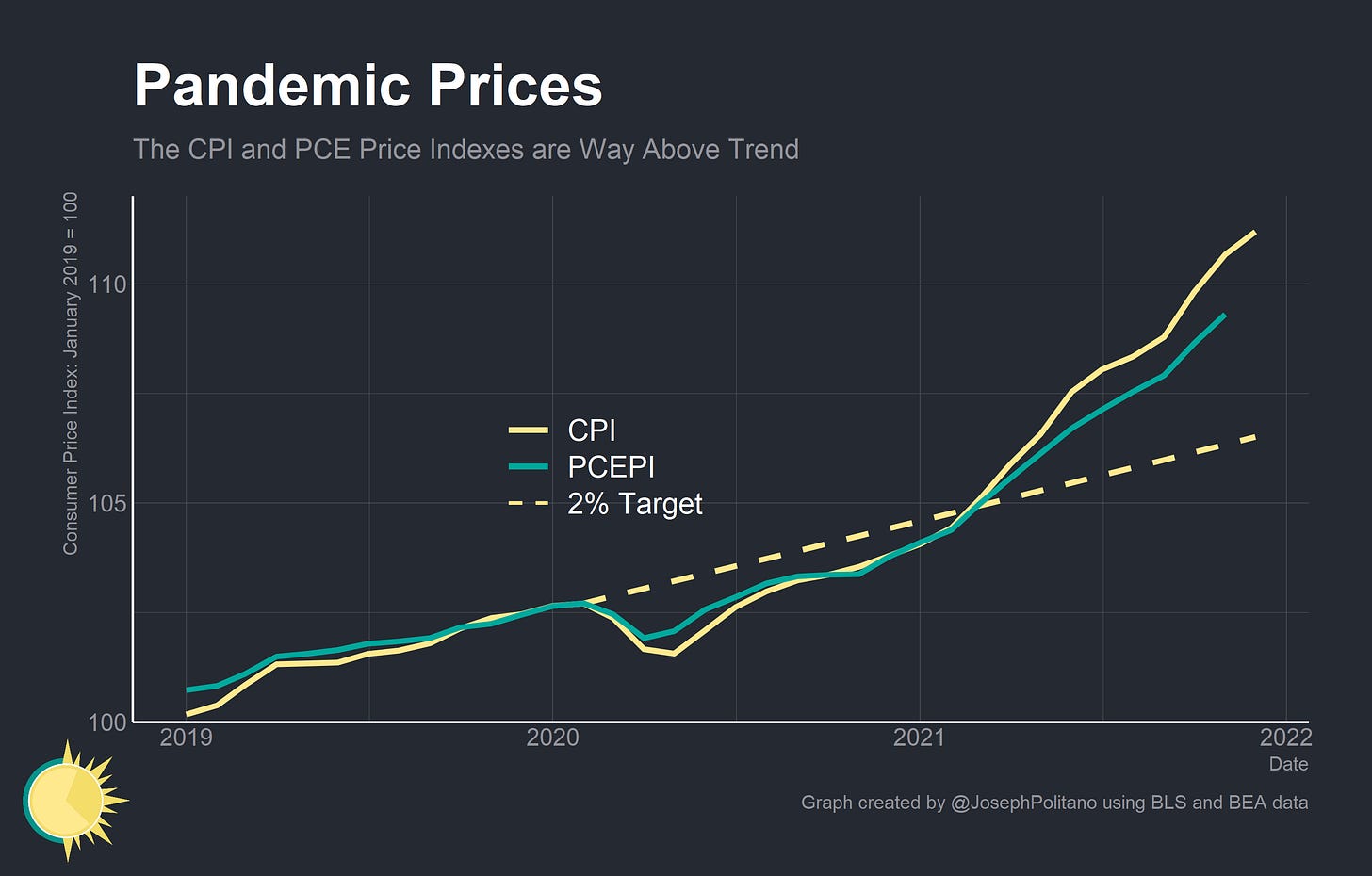

December was another month of high inflation with the Consumer Price Index (CPI) increasing 7% year over year and 0.5% since November. Core CPI, which excludes food and energy, rose by 0.6% month-on-month and 5.5% year-on-year. Prices for used cars and trucks moved up 3.5% in December. Gasoline prices inched down 0.5% over the month. Housing prices, which make up almost a third of CPI, increased 0.4% over the last month as well. CPI has significantly exceeded its prior 2% trend, as has the Federal Reserve’s target measure, the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCEPI).

Critically, headline and core measures of inflation are not excluding all the pandemic-induced price volatility. Goods—durable goods in particular—are behaving more like food or energy and less like normal. The trimmed mean PCEPI, which excludes the items whose prices have increased the most and least, rose 2.8% over the last year. This is high for the post-2008 era, but not terribly so—and it reveals the outsized impact a few categories have had on overall inflation. Luckily, it is prices in idiosyncratically-behaving goods that are likely to come down soon, even if price increases in the service industry cancel out some of this effect.

Durable Goods, Fungible Prices

Critically, this is not inflation caused exclusively by an excess of demand. Total consumer spending since the start of the pandemic is $1 Trillion less than would be expected given the pre-pandemic trendline, although the rate of spending is currently above-trend. Instead, this has been about a dramatic reallocation of demand. Americans are spending much less on services and much more on goods thanks to the pandemic.

The result has been an unprecedented jump in prices for durable goods relative to services. When I say unprecedented I mean it—a jump of this size has never occurred in American history. The natural tendency of the economy is for manufacturing prices to decline relative to services prices as production becomes more efficient over time and more workers transition to services. The massive positive shock to goods demand and negative shock to services demand caused by the pandemic should both renormalize as COVID fades.

The other side of the durable goods coin is that spending may sink below trend as the economy reopens. Durable goods are, well, durable—they should last several years before consumers need to purchase replacements. The rush to buy durables during the pandemic may be offset by a post-pandemic situation in which fewer people than expected want new durables. Either way, we are seeing the first trends of a reversal now: real consumption of durable goods is down for the first quarter since the pandemic started.

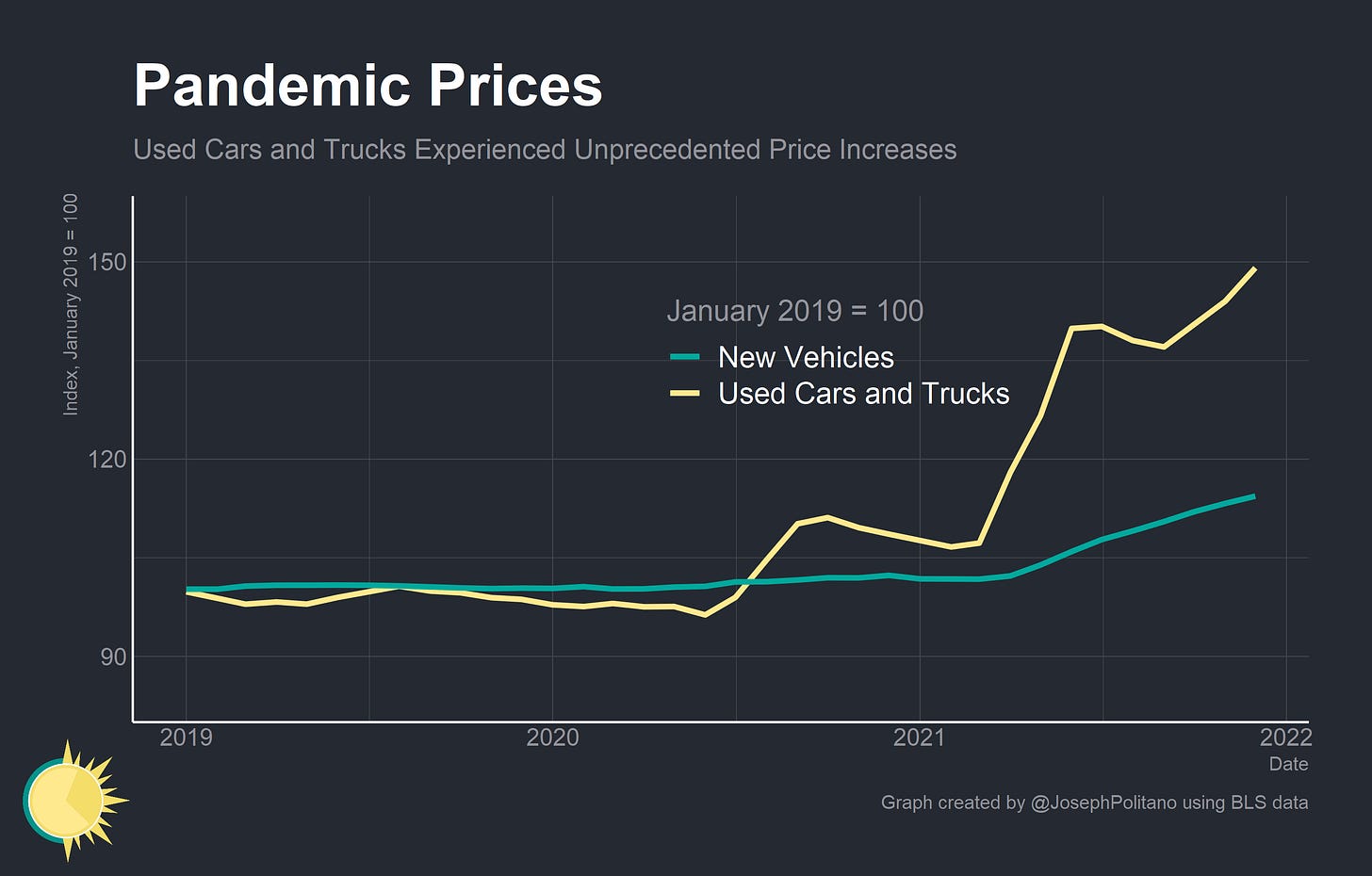

Motor vehicles are the major subsector where Americans are actually consuming fewer durable goods—though not for want of trying. As I explained in another piece, demand for automobiles has increased dramatically as Americans travel more and use public transportation less. Meanwhile, the chip shortage and other production issues have resulted in a shortfall of 3.5 million vehicles—with the end result being a massive jump in prices. The good news is that vehicle assemblies are up somewhat relative to their recent lows and most automakers expect fewer production disruptions, but it will still take a long time to close the shortfall.

Last month, the appearance of the Omicron variant looked as though it was going to pull down global oil prices (and I said as much in the piece on November’s inflation). While oil prices are still below their highs earlier this year, they have ticked up nearly 18% from their recent lows, and it is not likely that gas prices will continue shrinking in next month’s CPI print. Critically, US oil production has been extremely lackluster despite the jump in prices as the increased risk of the pandemic environment weighs on producers.

Looking Ahead

Looking ahead, there are some encouraging signs that inflation will be abating in the near future. For one, we are not seeing any signs of a so-called wage price spiral where rising wages feed into higher prices, which then cause demands for even higher wages. Salary growth is highest in the service sectors while price growth is highest in the goods sector—the exact opposite of what a wage-price spiral would predict.

Second, market-based measures of inflation expectations have retreated somewhat from their highs and remain near the Federal Reserve’s target. While 5-year inflation breakevens are at record highs, breakevens for the 5 year period starting 5 years from now are well within historical levels. In other words, markets are not worried about long term inflation. If you are concerned by 5-year inflation breakevens sitting at 2.87%, remember that these measures embed risk premiums in addition to real inflation expectations into their pricing. The DKW model, which attempts to adjust for these risk premia, has 5 year inflation expectations at 1.58%.

Finally, it is worth noting that aggregate incomes and spending remain largely on-trend. Outlays will likely remain above trend as consumers spend down some of their excess savings, but aggregate incomes should remain on-trend as higher labor income cancels out with reduced government transfer income. As long as nominal incomes remain on-trend, inflation will come down while the economic recovery continues.