Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 11,200 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

A few weeks ago, I was publicly lamenting the lack of action from Washington in response to the dramatic rise in inflation. Whereas the initial COVID crisis had spurred Congress to an exceedingly rare moment of bipartisan action, inflation had seemingly paralyzed both the White House and Congress. Negotiations for the Build Back Better Act had apparently collapsed, and 1600 Penn seemed like it was retreating to a messaging strategy in the absence of a comprehensive policy strategy to deal with inflation. The Federal Reserve was going to have to go it alone.

Consider me happy to have been proven wrong; the Senate (read: West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin), House, and President managed to pass the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) this week, a new bill composed of the collected remnants of the Build Back Better Act. Functionally that means all the energy, healthcare, and tax reform provisions that could be fit into a deficit-reducing package.

I am personally saddened by the loss of the transformational social care provisions in the original Build Back Better Act, and the IRA notably excludes any significant provisions to meet America’s yawning housing shortages. Though a shadow of its former self, the IRA still represents one of the most important bills in modern history. The importance of its healthcare provisions and climate provisions alone cannot be understated—though I believe they are best explained by others (David Roberts at Volts has two good pieces on the IRA’s climate benefits, and Vox has a good overall breakdown including the healthcare provisions).

Here I want to answer a simpler question: Will the Inflation Reduction Act…reduce inflation?

Critically, the bill takes an all-of-the-above attitude towards energy policy—focusing heavily on abundant production alongside investments in efficiency gains. That, coupled with recent actions from the administration and the permitting reform bill slated to be voted on later this year, has the potential to increase output and lower prices across the energy sector. Considering the fragile state of global energy markets and ongoing acute energy shortages, this bill comes at an extremely critical time.

Outside energy, however, the bill’s effects on inflation are likely to be too small to even be noticeable within the timeframe that matters for current monetary policy (1-2 years). Different models come to slightly different conclusions, but they all functionally say the same thing; the net effect of the Inflation Reduction Act on the federal deficit will likely be minimal in the immediate future, and therefore the effect on core inflation will also likely be minimal. Outside of energy, the Federal Reserve is still basically working alone.

Energy Abundance

Traditional climate economics has centered carbon pricing or cap-and-trade schemes designed to efficiently price the negative externalities of carbon (or other greenhouse gasses) in order to reallocate production and consumption away from carbon-intensive activities. Waxman-Markey, the last big federal climate bill with any serious hope of passing, contained a cap-and-trade system (though that was by no means the totality of the bill) and failed largely due to widespread opposition to that system.

In the intervening decade-plus since the failure of Waxman-Markey, federal climate policy efforts largely abandoned the carbon pricing or cap-and-trade proposals. Though they have passed in some other democracies (Canada, Japan, the EU, etc) and caused important emissions cutbacks, the American electorate simply doesn’t like them and the makeup of the Senate basically ensures they are nearly impossible to pass. Especially at a moment when energy prices are rising across the board and many fossil fuels are in acute shortage, the idea of introducing a tax on carbon emissions is a political and economic poison pill.

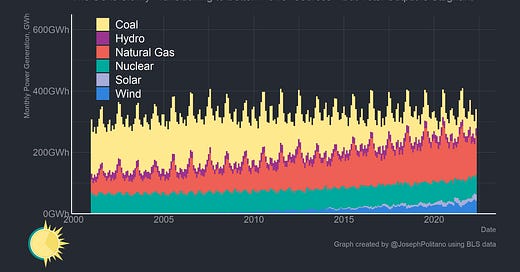

The second, equally important, change since the 2009 Waxman-Markey bill has been the unprecedented expansion of US natural gas production (which has increased nearly 75% since 2009 and largely supplanted less-efficient coal power) and the rapidly decreasing costs of solar and wind power. Learning curves meant that renewable capacity expansion pushed technology to improve, which pushed more capacity expansion, which pushed more technological improvement until the price of electricity from new solar capacity dropped 90% and the price of electricity from new wind plants dropped 70%. Both are now more than cost-competitive with new natural gas, coal, nuclear, or oil power generation—though fossil fuels and nuclear are better able to provide “baseload” power because they are more consistent energy sources. Even on the baseload front though, battery costs are down 90% since 2009—which helps to make up for solar and wind’s comparative unreliability. Coal power—which made up the bulk of US electricity production in 2009—now makes up less than wind alone.

Let’s not get too ahead of ourselves, though. In terms of total energy sources,(i.e, not just electricity but heating, driving, and so on) fossil fuels make up about 80% of American consumption compared to about 12% for renewables ex-nuclear and about 8% for nuclear alone. In other words, fossil fuels will still be the vast majority of American energy consumption in the near future—which is why it’s important that the IRA is an energy bill more than it is a strictly climate bill.

The energy provisions in the IRA are basically a grab-back of stuff for a multitude of different energy consumers and producers. In what I am dubbing the “cash for clunkers for climate” provisions, consumers get up to $7,500 to buy a US-made electric vehicle, $2,000 to buy a heat pump (an energy efficient dual purpose heating-cooling system), 30% off rooftop solar systems, $840 for electric cooktops, and up to $9k for electric panels/home insulation upgrades. All of these are functionally investments in more technologically advanced, safer, and more efficient products—which should reduce energy demand while making consumers strictly better off.

Green investment and production tax credits were renewed and changed to more direct payment mechanisms, making them more accessible to smaller producers with less financing access. Specific tax credits were created to keep existing nuclear power plants running—which may be partly why California Governor Gavin Newsom is scrambling to stop the closure of the Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant. The new Clean Electricity Production Tax Credit subsidizes nuclear, hydrogen, and geothermal power in addition to regular solar and wind. $700M is also allocated to help buildout research and a domestic supply chain for High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium Fuel, the stuff used to power modern, advanced nuclear reactors.

The Inflation Reduction Act also has critical provisions designed to buoy domestic fossil fuel production—namely, the legislation guarantees new leasing opportunities for federal lands in the Gulf of Mexico and Alaska. The bill also “prohibits leasing of federal lands and waters for renewable energy unless the government has offered at least 2 million acres of public land and 60 million acres in federal waters for oil and gas leasing during the prior year.” There are additional benefits for carbon capture, utilization, and storage strategies, which aim to capture and store the carbon emitted from fossil fuels before they enter the atmosphere. It’s a subsector that will need to be pushed down similar learning curves as solar and wind in order to reduce the climatological damage of fossil fuels wherever they remain necessary.

There’s also a critical second bill that Congressional leaders agreed to vote on in order to gain Senator Joe Manchin’s support—reform to America’s outdated federal permitting system. The provisions would cap the length of environmental review processes and allow the president to designate energy and infrastructure projects of national importance. That cap is important because the natural tendency of review processes is to get longer over time—people can sue you for not doing enough review but can’t sue you for doing too much review. Permitting therefore remains a key obstacle for both fossil fuel and renewable energy deployment while stopping more boring but essential infrastructure projects.

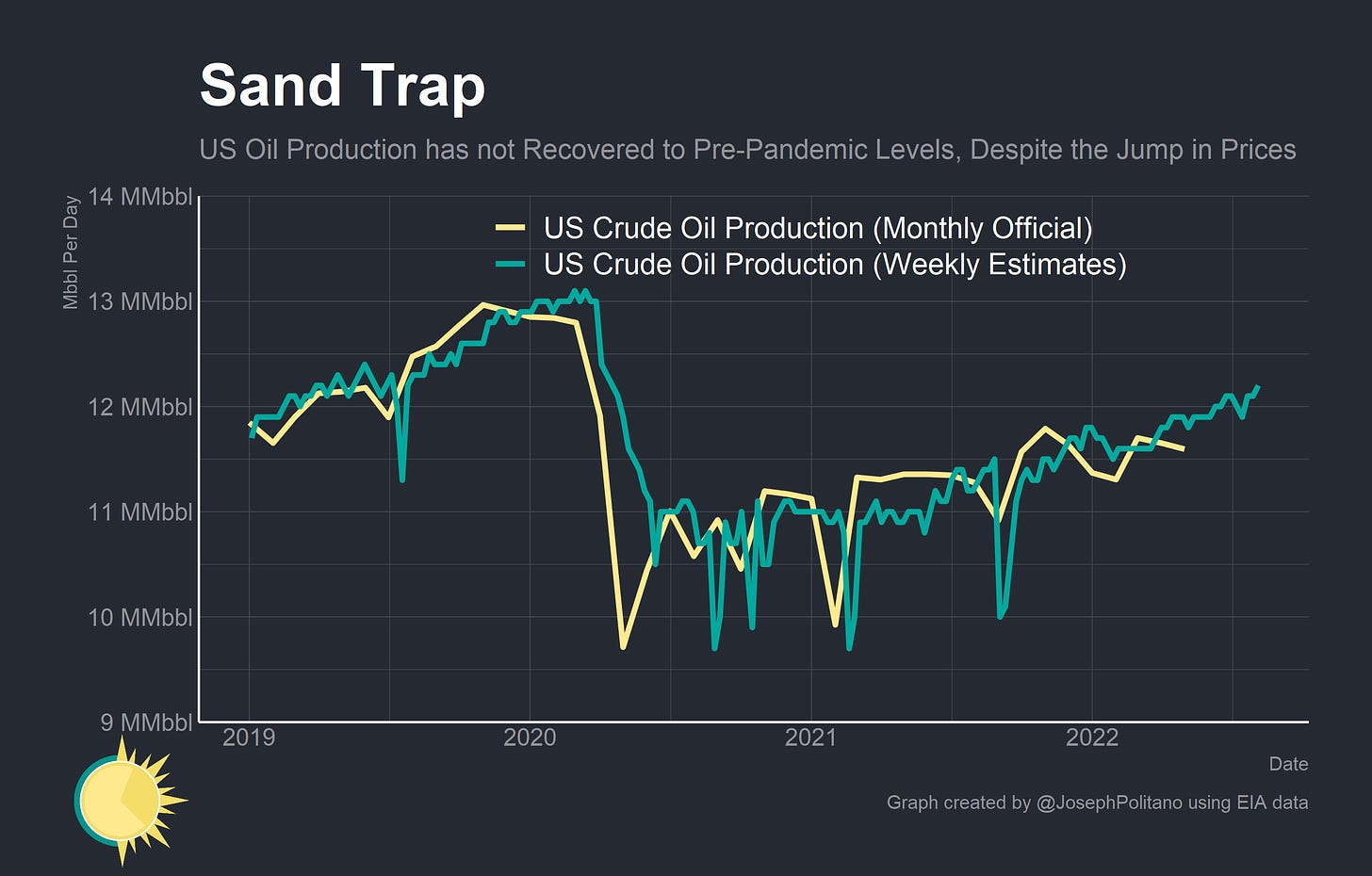

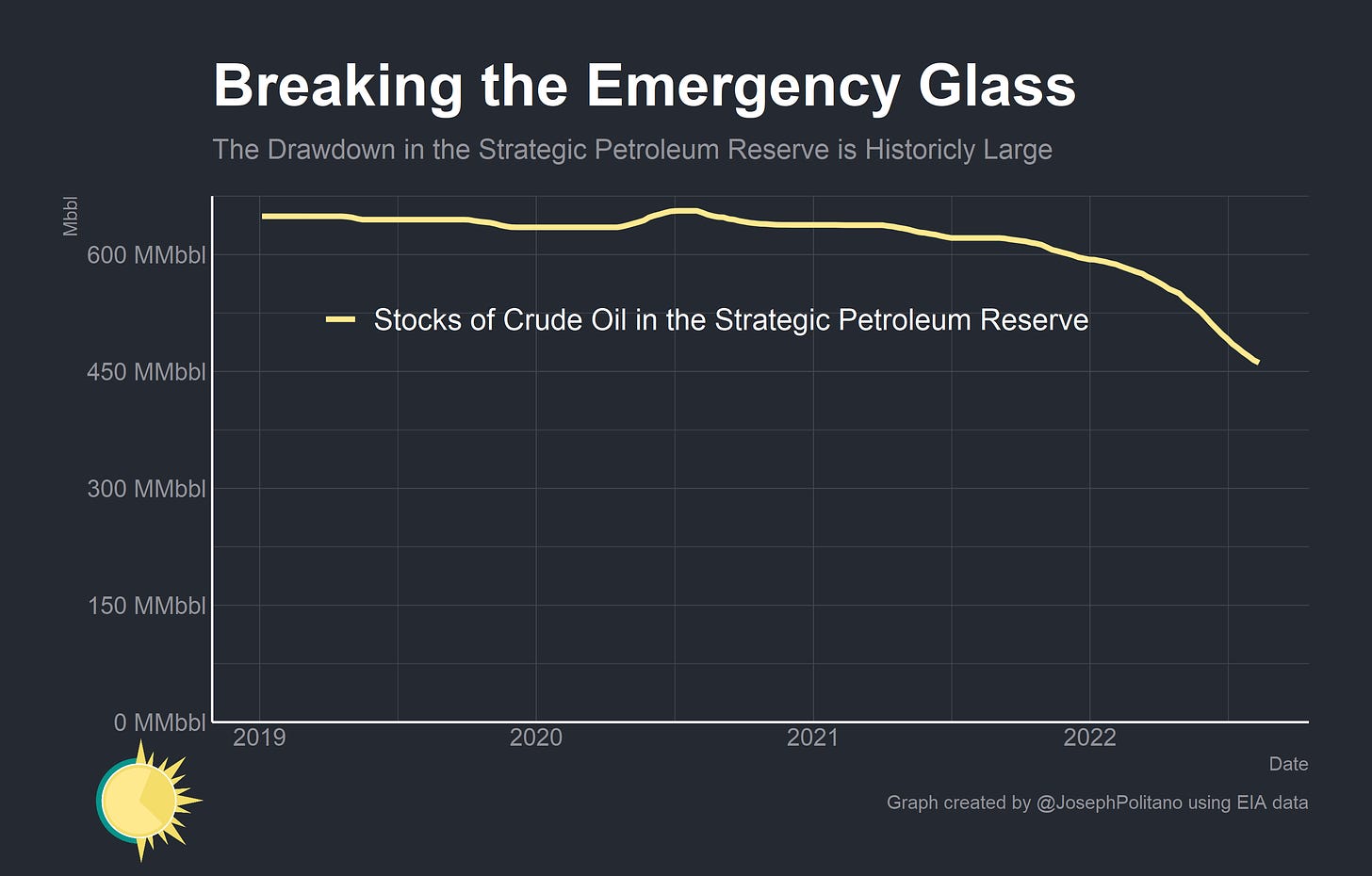

In the near future, this should all combine to represent greater output, more efficient consumption, and hopefully lower prices for domestic energy. But I think it is also important to remember that investments, prices, and decisions today are still affected by policies that take effect tomorrow. Diablo Canyon’s nuclear reactors are a good example—policies and subsidies that take effect in the future spurred action in the present to (hopefully) save the plant by creating certainty and changing incentives. The White House and Department of Energy are using similar authority to stabilize energy markets and lower spot oil prices through historicly large releases of crude oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR). This is, after all, the moment that the SPR was made for—global energy output shrank dramatically with the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and preventing wartime shortages is the SPR’s raison d'être.

However, there’s a new tool alongside the historic SPR releases that should make them even more impactful. The team at Employ America—a think tank I have tremendous respect for—has been advocating for the Department of Energy to submit fixed-price bids to refill the SPR in the future to pair with releases in the present. The general idea is that the SPR would release crude oil today and then sign a contract at a set price to refill that crude sometime in the future. That way oil producers have more certainty in how they invest—producers who sign a contract with the Department of Energy know how much they can sell oil for in the future and won’t have to worry about the kind of crashes that wiped out oil producers in 2014 and 2020. In a backwardated market—where the price of oil today is more expensive than the price of oil in the future—the combination of SPR releases and fixed price bids should lower prices today while still enabling necessary investment for the future—all while netting the government a tidy profit. The Department of Energy has submitted a notice of proposed rulemaking (a proposed regulation) that allows them to do exactly that—which may have already helped contribute to the recent decline in oil prices while also closing the gap between current and future oil prices.

All of this is many words to say one thing: the Inflation Reduction Act—paired with permitting reform and other tools available to the executive—will likely ameliorate some of the acute shortages in the energy market and thereby help reduce headline inflation and increase economic output.

Core Problems

The problem is outside of energy prices the Inflation Reduction Act is unlikely to have much measurable impact on prices. To understand why, I have to talk about monetary offset.

Generally, immediate fiscal spending is thought to have a positive fiscal multiplier; that is, new aggregate government spending will induce an increase in overall economic output. That will also likely manifest as higher prices, especially in an economy nearing capacity constraints. The reverse is true too—new taxes or a cut in government spending will induce a decrease in economic output and likely disinflation in the short term.

The problem is that in the long term a central bank trying to keep inflation constant must “cancel out” or offset this new fiscal stimulus. If the government announces a set of new spending programs to take effect in two years the central bank should raise expected future interest rates by an amount designed to offset the new spending in order to keep the economy balanced. The same, inverted, is true if spending is cut—the central bank should decrease expected future interest rates to offset the decline in fiscal stimulus. Even if the new government policies permanently increase or decrease long run real output, with enough warning the monetary policy authority should be able to keep the economy balanced.

In practice the Federal Reserve and other central banks aren’t perfect at this offset (have you checked the inflation numbers recently?) but monetary policy is still more like the captain of the ship and fiscal policy is more like the currents. Yes, the ocean will push the ship around (and the ship, when stranded, will need boosts from the water) but it's still fundamentally up to the captain to get the ship to the destination. The fact that fiscal multipliers are positive and nonzero in the short run indicates that monetary policy can't (or doesn't) immediately offset fiscal spending—possibly for financial stability reasons.

Take the IRA's healthcare provisions as an example. The bill caps out-of-pocket prescription expenses for Medicare recipients and allow for the government to negotiate Medicare drug prices—both of which should lower these drug prices and increase efficiency eventually. However, these provisions won't start taking effect until 2026, far enough away that they simply won't matter for short-run inflation. By the time they do kick in the Federal Reserve will have already taken them into account and compensated for them when setting monetary policy. It's a similar story for the bill's deficit reduction—most of it happens far enough in the future that monetary policy can fully account for it.

However, if the bill reduces the deficit in the short-term it can still provide the kind of negative fiscal impulse that could pull down inflation. So does the bill affect the short-term deficit? Not by much. The Penn Wharton budget model expects a $30B increase in the deficit during the first two years, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget expects a $30B decrease, and the Congressional Budget Office expects a less than $20B decrease. I have problems with each group's modeling, but functionally all of those numbers are extremely small compared to a $25T economy, and all are even smaller than the Bureau of Economic Analysis’ estimate for the annual cost of student loan interest forebearance alone ($38B). There's an added wrinkle that a lot of the tax increases come from housholds with higher marginal propensities to consume (the 1% tax on stock buybacks will primarily affect wealthier shareholders, for example) and a lot of the spending increases go towards subsidizing consumption (the electric vehicle tax credit, for example). That's good for reducing inequality, but could mean temporarily increasing consumption demand while reducing saving at a time when supply chains are at capacity and consumption is constrained. Again though, the net effect of the bill on core inflation is likely to be immaterial because of how small the changes in net spending are.

Conclusions

So the Inflation Reduction Act, coupled with permitting reform and other executive tools, could improve US energy markets and reduce prices. Outside of energy, though, the bill is likely to have minimal effects on inflation.

That's not to detract from the other important accomplishments contained within the IRA. Modeling estimates that it will represent the biggest net reduction in US carbon emissions by any bill in history, the healthcare provisions are an important step forward for an American healthcare system plagued by inefficiency and overpricing, and the bill's tax reforms promise a more efficient and equitable system. The future of inflation, however, largely remains with the captain—at the Federal Reserve.