The Interpersonal Economy - Automation, Employment, and You

The Future of Work Lies in Knowledge Industries and Interpersonal Services

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Automation is one of the most headline-catching aspects of the modern economy - perhaps you’ve seen the oft-cited Brookings study that 25% of American jobs are at risk for automation or watched CGP Grey’s 2014 video “Humans Need Not Apply.” With rapid advances in self-driving cars, artificial intelligence, and precision robotics, it feels as though human labor and intelligence is on the precipice of being made obsolete. The idea that human labor will be supplanted by machine labor has been around for centuries - Keynes famously postulated that we, the grandchildren of his generation, would only need to work 15 hours a week.

Keynes, however, was wrong. The decades that followed his life represented the single-biggest expansion of formal employment in human history. Instead of destroying jobs, the automation of the late 20th century enabled work so vast that it was able to absorb a dramatic increase of women and African-Americans in the US workforce. The average American worker spends 34 hours a week on the job today, a significant but unexceptional decrease from the 39 hours a week of Keynes’ time.

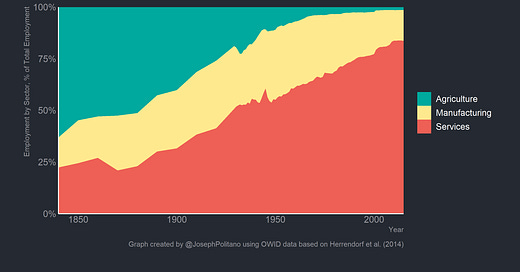

The truth is that the American economy, alongside the economies of most high-income countries, experienced a dramatic shift when transitioning into a post-industrial economy. Instead of manufacturing or agriculture, the vast majority of workers nowadays are in the service sector. Health care, education, law, finance, food service, and hospitality have experienced massive increases in employment over the last few decades. Manufacturing and agriculture’s share of employment generally lost ground to services, and today more than 85% of American workers are in the service sector.

Increases in productivity through automation tend to manifest as additional consumption and production, not in the elimination of labor. Even that Brookings study admits that automation is extremely unlikely to reduce total work even as it replaces individual tasks. The US has actually struggled to boost labor productivity over the last few decades, meaning the country needs more automation, not less. Since there is also a near-infinite amount of services that humans want from other humans, there will be no shortage of jobs even when robots exceed human capabilities in all aspects. The change, however, will have profound effects on the economy and the lives of people across the globe - kickstarting what I call “The Interpersonal Economy”

How Does Automation Affect the Labor Market?

In 1850, more than 50% of American workers were in agriculture. Today, less than 1% of them do. While manufacturing jobs have grown slightly as a share of total employment, the real story has been the spectacular growth of service sector occupations from 25% in 1850 to almost 85% in 2015. Increasing productivity in the agricultural sector fed the growth of the manufacturing sector, and increasing productivity in both of these sectors fed the growth of the service sector. Automation, in this case, did not eliminate the need for work but rather increased the complexity and quantity of production while changing the comparative advantages of human labor and machine “labor.”

First, it is critical to examine the increasing complexity of production through automation. This does not mean that the complexity of the production process itself is increasing, but rather that the complexity of finished goods is increasing and the range of available goods is growing. Advances in manufacturing productivity brought us more computers, but they also increased the complexity of computers and the range of tasks that can be accomplished with a computer. Automation of basic computing tasks eliminated the job of “human computer” but enabled a vast increase of jobs in programming, video production, gaming, streaming, IT, and all the services that support those jobs. This boosts the gross output of the economy while providing additional opportunities for work and new production processes.

Second, we need to see how comparative advantage determines the tasks performed by humans. Comparative advantage is the elementary economics idea that certain units - countries, firms, people - can always benefit from trading with others and specializing in producing the goods or services for which they have a lower opportunity cost. Though plenty of economists have poked holes in the theory’s applications, it still represents one of the bedrock ideas of economics. When mathematician Stanislav Ulam challenged economist Paul Samuelson to find one social science theory that was true and non-trivial, comparative advantage was his answer. The non-trivial part is that both units can benefit from specializing in items for which they have a comparative advantage even it one unit has an absolute advantage in all areas. If you imagine trade between human labor and machine “labor”, changes in the opportunity costs between human and machine production will change their specializations, but there will always be benefits to the two specializing and trading. This is in essence what the industrial and post-industrial revolutions have wrought: a change in the comparative advantage of human labor from agricultural and industrial work to service and interpersonal work. Equally critically, there will remain a place for human labor to improve total production even when machines outclass us in every possible way.

The growth in service jobs has not come from a reduction in manufacturing jobs, even though agricultural jobs have significantly decreased. Rather than pulling workers from manufacturing and agriculture, the service sector mostly grew by pulling workers into the labor force in the first place. The prime-age employment-population ratio, which measures of the percent of people 25-54 who are working, steadily increased from about 62% in 1960 to about 82% in 2000. This was driven by a massive increase in women and African Americans in the labor force as the elimination of some of the legal obstacles to work coincided with large wage growth across the country. Essentially, the service sector pulled people off from the sidelines of the labor market rather than directly poaching workers from manufacturing jobs. Automation, instead of destroying jobs, has dramatically increased the demand for formal employment and allowed people out of household production and into higher-paying jobs. Critically, service sector jobs can actually amplify the productivity of agricultural and manufacturing jobs through the same comparative advantage channel that amplifies productivity when human labor and machine “labor” trade.

While employment by factor changed dramatically, it is also worth noting how consumption and production by factor changed throughout the latter half of the 20th century. In 1950 America’s personal consumption expenditures on goods represented 40% of GDP, and services represented only 25%. Just before COVID-19 that ratio had more than fully reversed - consumption of services represented 45% of GDP and consumption of goods represented 25%. The share of GDP spent on production of goods is even lower, as the United States imports much of its goods from abroad. This critical shift in demand is a result of boosting productivity in the agricultural and manufacturing sectors - while there are limits to the amount of food one person can eat and the amount of physical goods they can own there is basically no limit to the amount of services they can purchase. The result is an America where consumers spend more money at restaurants that at grocery stores and more money on recreational services than motor vehicles.

Throughout all these tectonic shifts in the economy, labor’s share of national income has barely budged. The graph above shows how income across the whole economy has been distributed among the two factors of production, labor and capital (which includes land). The recent decrease in labor’s share of national income has been thoroughly examined with explanations ranging from the housing shortage to superstar firms to the rise of rapidly-depreciating capital assets like software, but in truth labor’s share of income remains near its historical average. Even the slight decline in labor’s share of national income is cause for concern, but it is by no means the apocalyptic future envisioned by some where the owners of autonomous machines receive the lion’s share of income in the economy. In a competitive economy, whenever automation pushes the average cost of production extremely low either the quantity produced would explode as the price decreased or low profitability would push the firms to abandon the product. The former is what has happened to music, where the reduction in costs led to the explosion in quantity offered, and the latter is what happened to tape recorders, where decreasing prices caused by technological improvements forced the product into irrelevancy.

This is not to say that we should not care about the inequality effects of automation. There has been a measurable downward shift in labor’s share of national income in many high-income countries and inequality among workers has has been growing as pay for highly-educated workers has increased faster than average. However, government social benefits to people have expanded from approximately 3% of GDP in 1947 to 10% of GDP in 2019. That growth is perfectly consistent with an economy with growing automation and pre-transfer inequality where a government with greater state capacity redistributes wealth to combat inequality. If inequality continues to grow as automation continues, it is likely that government social benefits in democratic nations will continually increase as well. A world where increasing economic growth through automation is redistributed through efficient taxes on consumption and carbon emissions is one we should welcome, not fear. Indeed, further automation is the only way we as a society will be able to afford universal basic income or other guaranteed income proposals.

The Interpersonal Economy

“Two separate beings, in different circumstances, face to face in freedom and seeking justification of their existence through one another, will always live an adventure full of risk and promise”

Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex

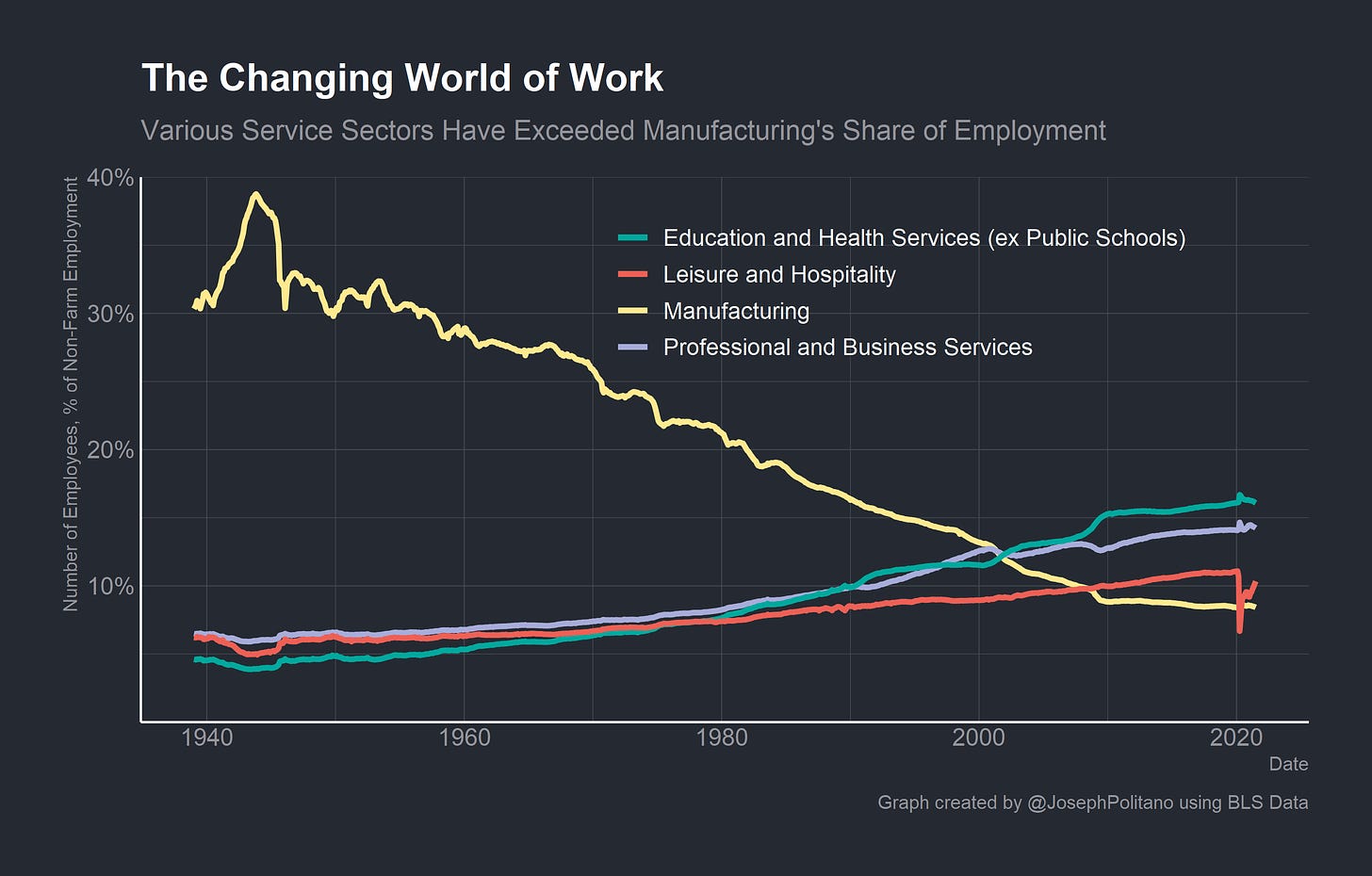

It is worth examining where the current and future comparative advantages of human labor lie in a world of accelerating automation. While American employment in manufacturing has been steadily decreasing for decades, employment has been rising dramatically in knowledge and interpersonal services. Knowledge services include specialized professional, scientific, technical, and administrative work while interpersonal services include work based in social interactions like childcare, leisure, and hospitality. At the intersection of these two are sectors like health care and education that require a strong balance of knowledge and social skills.

In 1950, nearly 50% of American workers were employed in manufacturing. Nowadays, less than 10% of Americans are, and more people work in education, health services, hospitality, and professional services than in manufacturing. The growth of knowledge work is a direct outgrowth of the high level of productivity in the American economy - it is more productive to work as an engineer designing cars rather than to work on the cars’ assembly line. It also more productive for the engineer to pay for a master’s degree to invest further in her career, and it is more productive for her to pay a daycare to look after her children while she is studying. This chain of services, even though none are directly related to the physical construction of cars, all contribute meaningfully to increased productivity and additional production of cars.

Interpersonal labor complements knowledge labor even further - day care, healthcare, and education all represent direct investments in human capital that increase future productivity. However, it is in interpersonal interactions that true value of this work lies. Teachers know that part of their job is to teach the subject matter, but another is to help build the interpersonal skills children require to be part of functioning society. Empathetic medical care improves patient outcomes, and talking to a therapist improves mental health. The jobs of bartenders and baristas could be automated away with sufficiently complex vending machines, and servers’ jobs could be eliminated by having customers order online and pick food up directly from the cooks, but this is not happening everywhere. In other words, people go to coffee shops for the shop and the barista, not for the coffee. There are contexts where people just want to pick up food and go, but the comparative advantage for human labor lies in the social interactions between people. It lies, as de Beauvoir put it, in the wondrous thrill of the justification of our own existence through other human beings.

Alex Williams from Employ America recently wrote a post titled “Under Full Employment, Your Job Could be ‘Anime Appraiser’.” In it, he crafts an exceptional, lighthearted discussion about the role cultural production plays in creating full employment. To quote directly:

Culture is nonrivalrous, and as long as the purchase of it creates wages that feed the rest of the productive system, it will serve the role of Keynesian “sumptuary” consumption or Bataillean “expenditure without recompense,” by generating needed demand without generating excess capacity.

I take a bit of umbrage with how the article plays down the consumption of entertainment when compared with its production, but the primary reason I’m bringing it up is that online entertainment is the pure essence of the interpersonal economy. The explosion of productivity wrought by the internet has resulted in the greatest library of entertainment ever created by mankind, and it is still growing at an accelerating pace. Creators work exceptionally hard to produce content, and those who commit to building an online audience are building interpersonal relationships and community alongside their content libraries. This is the core of what I would call “experiential services” - services whose worth is almost entirely defined by the experience generated for the consumer. Modern success in large chunks of the entertainment space is built through the community you craft with your audience and the social (or parasocial) relationships you form. That is why virtually every major YouTuber now has a discord and Patreon - they are selling micro-communities as much as they are selling entertaining content. This end result is Noah Smith making approximately $25,000 a month from blogging or a YouTube channel dedicated solely to in-depth analysis of every single episode of “Avatar the Last Airbender” that makes $3,000 a month on Patreon alone.

This should not be construed to discount the work that comes with being an online content creator. These jobs are no less inherently valuable than traditional work, and can carry extreme workloads and stress levels. Entertainment and community are core pillars of the human experience, and it is more than natural that demand for them would increase as living standards rise. My point in bringing them up is just to illustrate that the internet and computers have opened up incredible new opportunities for the production and consumption of social entertainment. The economy is built on humans’ demands for utility and happiness, and the internet age has dramatically amplified the possibilities for happiness generation.

Obviously, only a select few people can make their living through content creation. My only point in bringing it up is to illustrate the ways that human beings will identify their comparative advantages in an increasingly automated economy. Employment categories that were not even formerly tracked by the Bureau of Labor Statistics 30 years ago now represent the fastest-growing fields in America. 10 Million more people work in healthcare than did in 1990 thanks in no small part to medical technology advances that have dramatically increased Americans’ lifespan, boosting demand for old age care. Given that some of the healthcare employment is due to inefficiencies in America’s unique healthcare system, it might be better to look at accommodation and food service, where employment more than doubled over the last 30 years. Even the knowledge-based production adjacent fields of administrative, professional, and technical services have almost doubled! The range of service jobs is increasing while their pay and productivity is rising because of automation, not in spite of it.

Humans will remain good workers for certain hard-labor tasks - after all they are essentially a supercomputer with fully articulated movement that can run on coffee and pizza in a pinch. However, the bulk of growth in the American economy will come from the interpersonal and knowledge sectors as automation continues to grow. There is no risk of humans losing all forms of comparative advantage in the near future, and there will be no shortage of productive, well-paying work if policymakers continue to push demand-side growth for the foreseeable future.

Conclusions

It is easy to stumble into the trap Paul Krugman fell into when an old offhand comment about the internet’s inability to accelerate economic growth got him relentlessly mocked by online commenters. I consciously avoided any discussion of the future capabilities of AI, robotics, or the internet in this post, as I frankly do not have the experience necessary to accurately talk about these topics. I do have enough experience with economics to know that an economy governed by human demands and human ambitions will have a place for human work in the future. In fact, America could use more automation - labor productivity has grown at a much slower rate since the 2008 recession stymied aggregate demand.

This discussion has centered America because it is the world’s largest economy and is constantly pushing the technological frontier, but it is worth noting how different America’s situation is to the rest of the world. 50% of workers globally are in the service industry and 26% are in agriculture, compared with 80% in services and 1% in agriculture in the United States. Despite this, America has the third-largest agricultural sector on the planet - thanks in no small part to America’s GDP per capita being six times the world’s. Given how many people across the globe suffer from extreme poverty, there is no shortage of work to be done to get them to the standard of living enjoyed in high-income countries. Given how many people are threatened by climate change over the next century, there is no shortage of work to be done to protect and preserve the planet. We should focus on using automation to boost economic growth, increase living standards, and redistribute money rather than worrying about its effects on the labor markets of the far future.

In the extremely long run, it is possible that the limits of the human economy will eventually be reached. At some point the economy might be so large and complex that we either run into physical limits to growth or decide to satiate all our demands without working. However, these are ideas that belong either in the pages of science-fiction novels or alongside discussions of the heat death of the universe - they are not relevant to the economics of anyone living today. It strikes me as the same vein of thinking that lead Victorian era Londoners to worry that their city would not be able to clean up after all its horses if the economy kept growing - narrow extrapolation of current trends extremely far into the future without examining underlying assumptions or implications.

Keynes’ famous quote “In the long run, we are all dead” is often misunderstood to mean that we should not concern ourselves with the far future. In actuality, Keynes was critiquing the value placed on schools of thought that only concerned themselves with long-run equilibrium and said little about addressing the “tempestuous seasons” that occur in the short term. In this respect, Keynes was completely correct - concerns that automation will eventually completely eliminate human labor are not relevant to discussions of today’s economy.