The New Geopolitics of American Trade

Amidst War and Sanctions, US Trade in Energy and Semiconductors is Taking on Renewed Importance

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 18,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

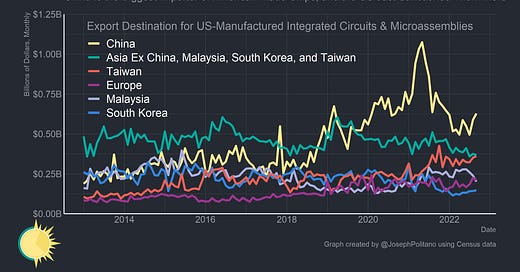

American international trade has become increasingly fraught and political over the last several years. Starting with Trump, the US government has grown increasingly hostile towards trade with China, culminating in a recent export ban for advanced semiconductors. Broad sanctions were placed on Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine earlier this year, cutting Russian industry and households off from critical supplies and consumer goods. “Friend-shoring”—shifting trade relationships from hostile or rival nations to allied or nonrival nations—has become the newest hot topic in Washington.

But it’s not just American weapons of trade wars—or real wars, as in the military supplies sent directly to Ukraine—that are changing the nature of global trade. America’s role as the world’s largest producer of oil and natural gas has made it a key supplier of scarce energy commodities, especially to Europe. A shortage of motor vehicles, parts, and other equipment has buoyed America’s trade with its northern and southern neighbors. Global agricultural shortages have pushed up American corn exports while shortfalls in European chemical and pharmaceutical output are being replaced by American exports. The nature of America’s geopolitical trade relationships has shifted rapidly during the pandemic and will play a key role in the future path for America and the world.

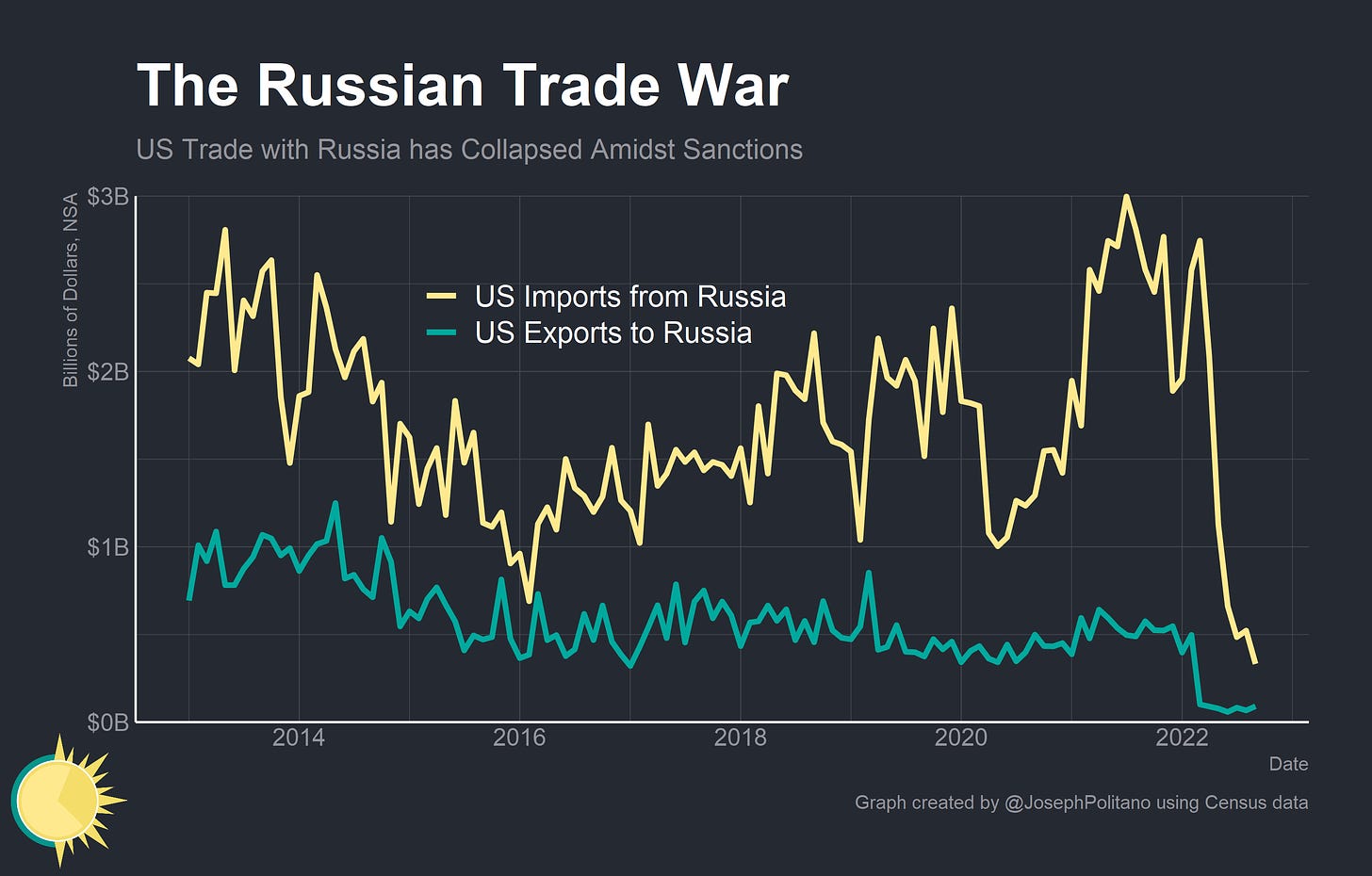

The Russian Trade War and European Energy Crisis

The most sudden shift has undoubtedly been the allied response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The US, alongside the European Union, Japan, Canada, South Korea, Australia, and others, have implemented harsh sanctions that have severely damaged the Russian economy. The US, having relatively little trade with Russia to begin with, has essentially cut Russian markets out. Imports are down 88% and exports are down 82%—lower than during the Russian financial crisis of 1998. While sanctions did cause America to lose access to valuable Russian feedstock for petroleum refineries, the combined force of export sanctions has inflicted significant damage on the Russian economy and bought time for Ukrainian forces to mount a strong defense.

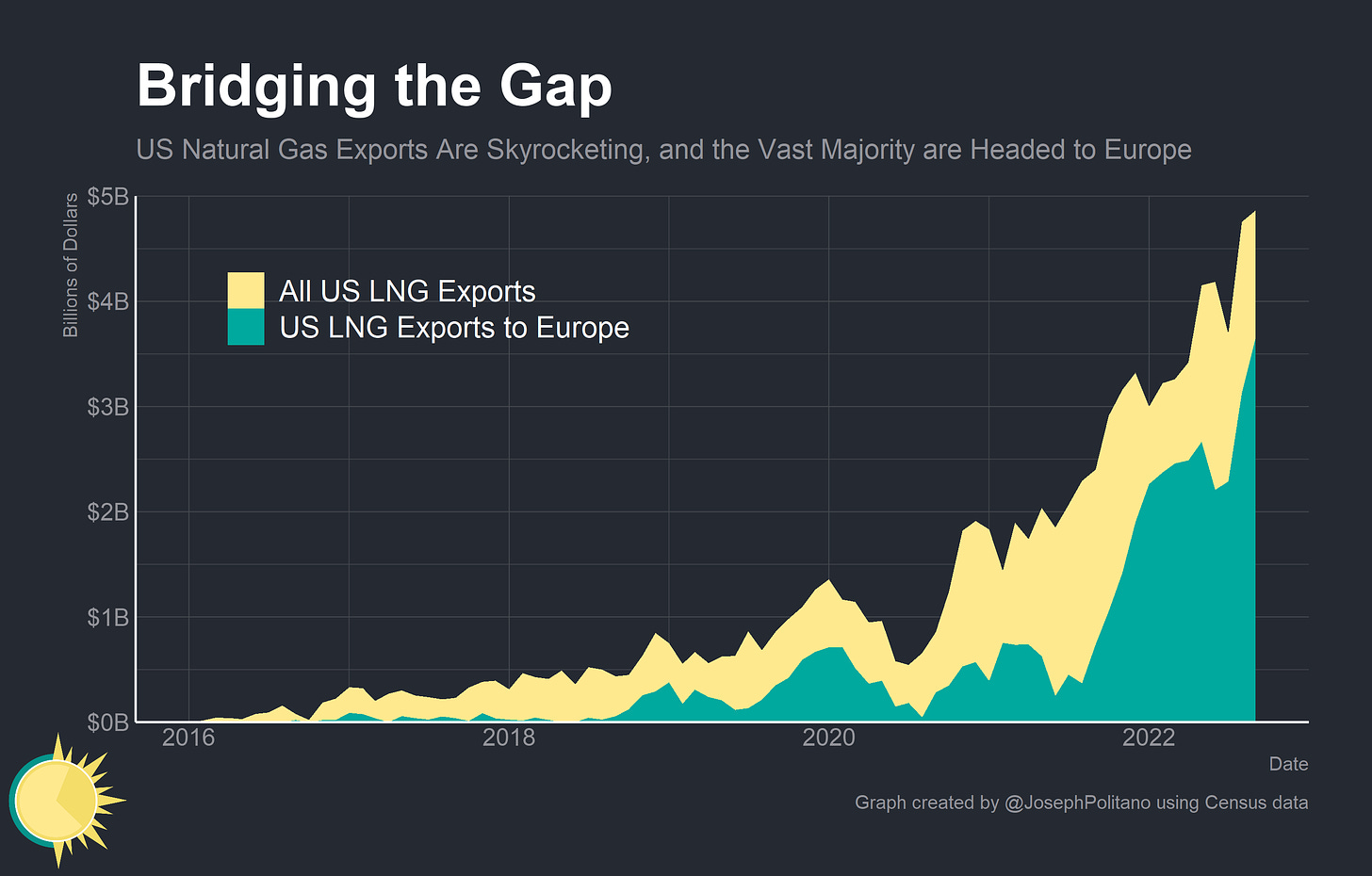

In response to sanctions and Russia’s worsening position in Ukraine, Vladimir Putin has cut off more and more of Europe from critical natural gas supplies. America responded by leapfrogging into the number one global exporter of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) and becoming one of the largest sources of natural gas for the European Union. American LNG exports have climbed from essentially zero just 6 years ago to nearly $5B a month, and are still rising. US LNG exports now look on pace to rival the total natural gas consumption of California and Florida combined.

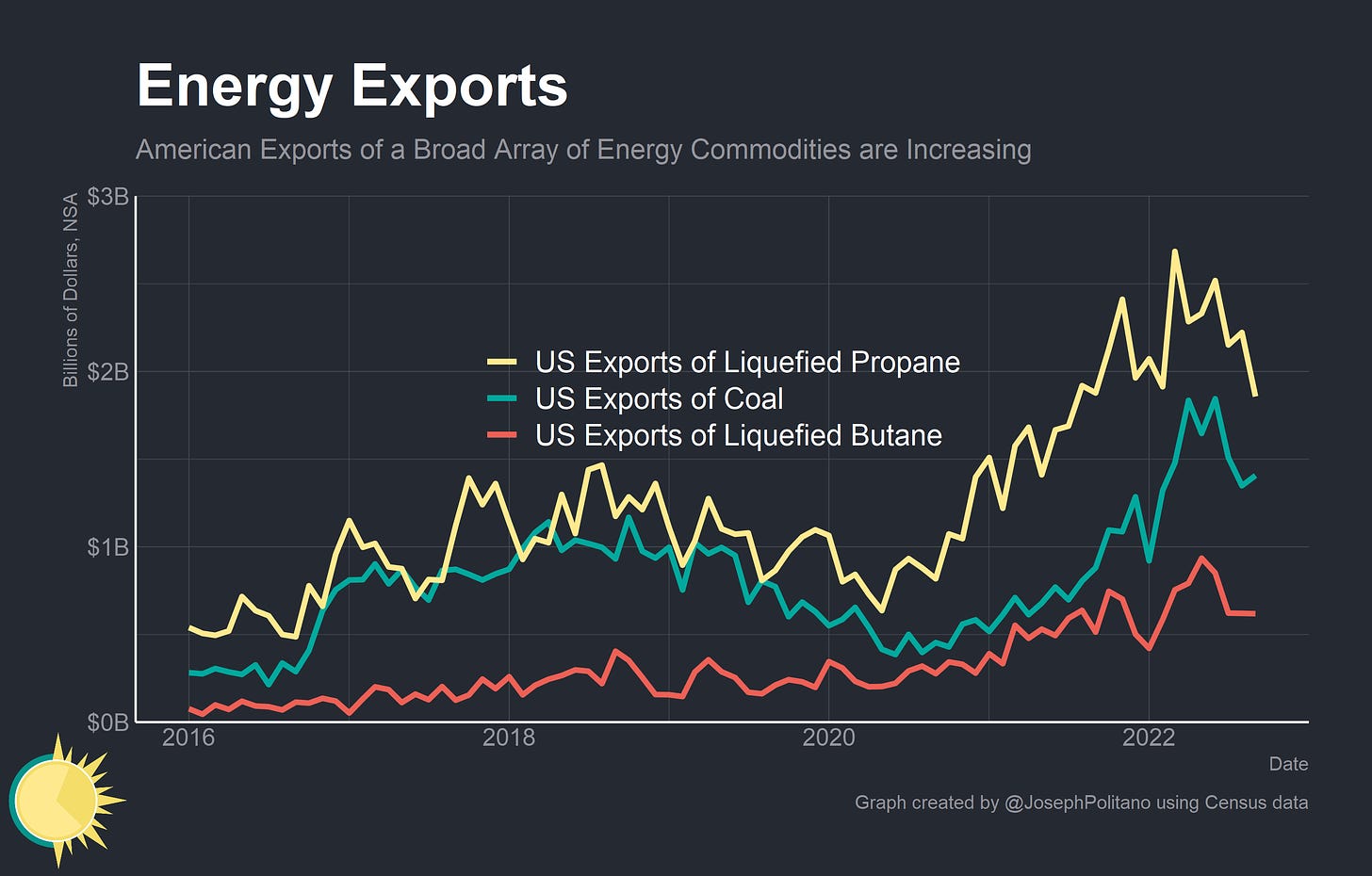

It’s not just LNG, though—and it’s not just Europe that American energy exports are supporting. US exports of coal, propane, and butane have all skyrocketed as prices and unmet demand for energy commodities spike. Coal production is still sliding as the fuel is phased out, but domestic butane and propane production have been notching new record highs alongside the growth of the natural gas industry. These products aren’t headed to Europe in much greater shares, but they are still helping to alleviate global energy imbalances.

Crucially, although America has seen its refining capacity shrink since the start of the pandemic the country’s dollar-valued net exports of refined petroleum oils are closing in on ten-year highs. That’s thanks to the dramatic increase in refining margins—the price to convert crude oil into gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and other refined products—and America’s role as a refinery powerhouse. The US, despite being the largest producer of crude oil, still imports crude on net for refining and re-export, making the country a critical supplier amidst the ongoing refinery capacity crunch. All of this has combined to help make the United States a net energy exporter for the first time in modern history and has helped to buffer democratic nations against reliance on autocratic energy exporters.

Friend-Shoring and Decoupling with China

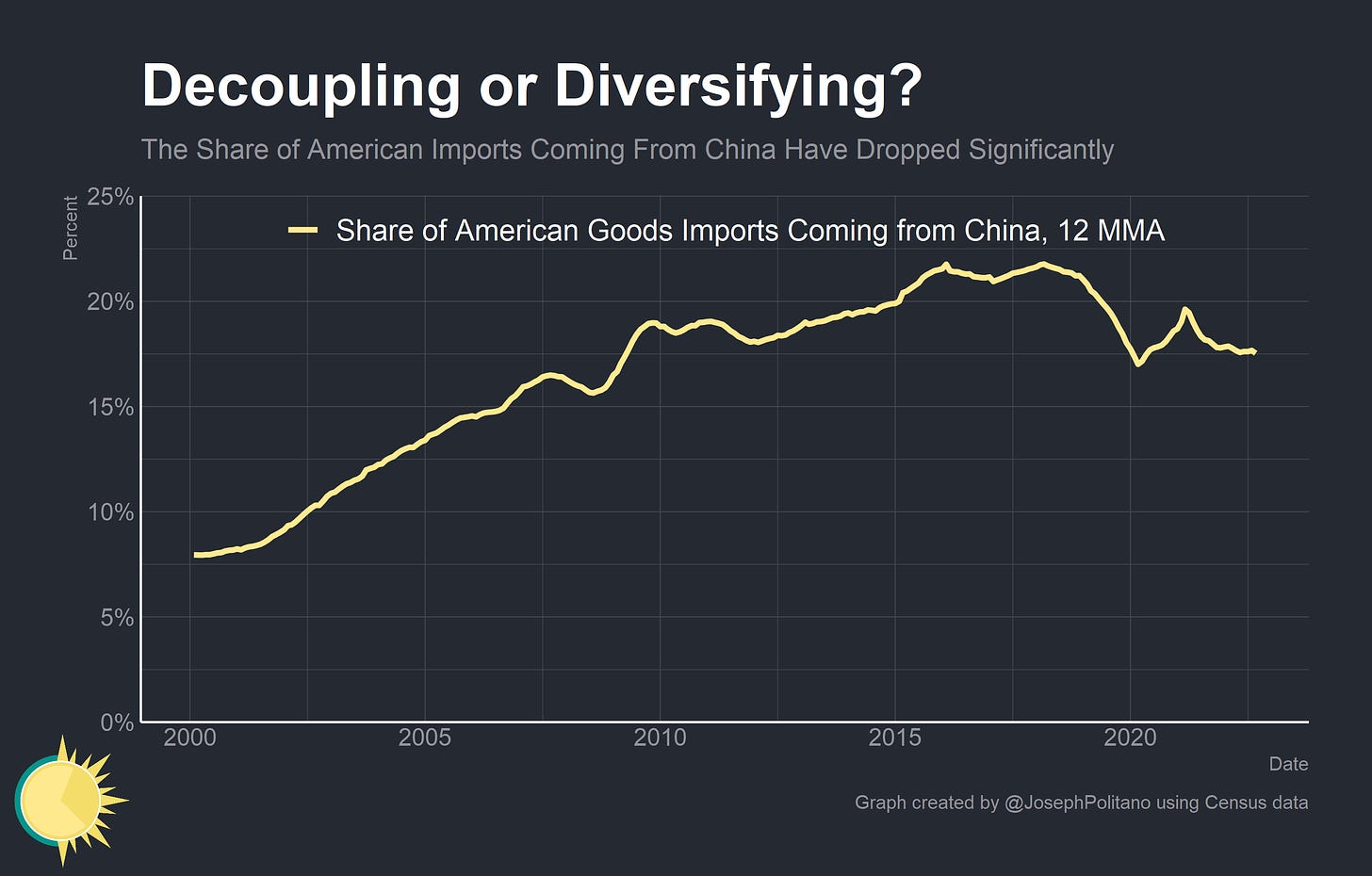

At the same time, America’s long-contentious trade relationship with China appears to be weakening since the start of the pandemic. China remains America’s biggest source of imported goods, but the share of imports coming from China has dipped by almost 4% since the start of 2019, erasing more than a decade of gains. The trade war instigated by President Trump during his term has continued into this administration and still has constricting effects on US trade flows with China—although supply-chain congestion is also definitely still limiting transpacific trade.

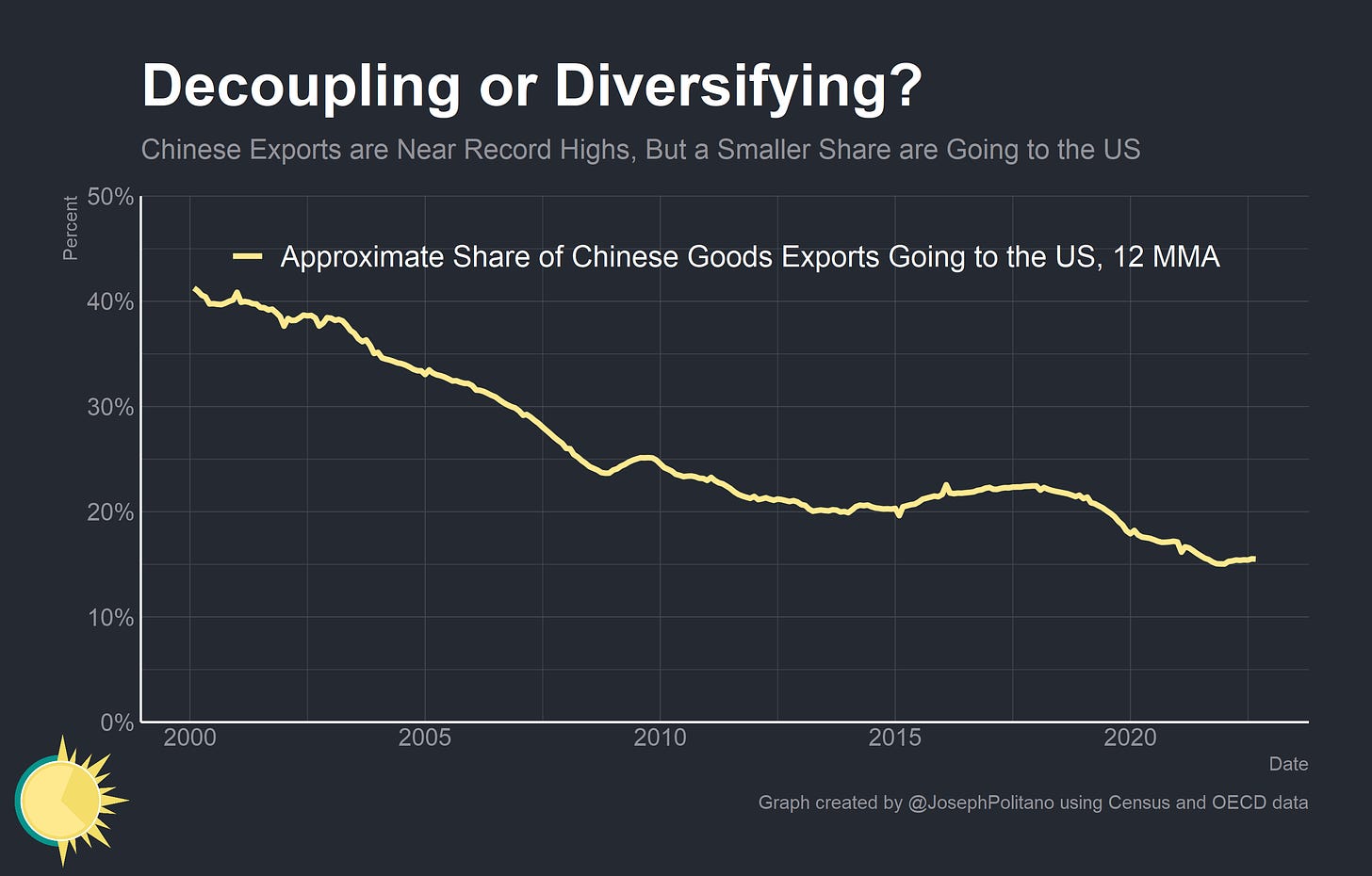

On the flip side, the share of Chinese exports headed to the US has also declined to a new low of only 15%. China’s trade surplus is at historic levels as the country prioritizes exports over domestic consumption amidst COVID-zero policies, but those trade surpluses are with Europe and Asia more than with the United States. So if not China, then where is the US getting its record-high amount of imports from?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.