The October Employment Situation

A great month for the labor market sees employment jump by 531,000 and unemployment drop to 4.6%

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

This is part of a new series where I will be breaking down regular economic data releases like inflation, employment, labor turnover, GDP, industrial capacity, and so on in addition to my usual Saturday posts. Expect 2-3 short breakdowns on an irregular schedule each month. Any input or feedback on these breakdowns is welcome as they are a work in progress.

The labor market improved significantly in October as the US added 531,000 jobs and the unemployment rate declined to 4.6%. In addition, revisions to previous months’ unemployment data added another 626,000 jobs. This still leaves the US millions of jobs short of pre-pandemic employment levels and even farther behind the expected employment growth trend. Pandemic-affected sectors like leisure and hospitality continued to suffer, with employment in accommodation and food services basically stagnant.

In the Aggregate

After stalling out at 78% for two months, the prime age employment-population ratio increased slightly to 78.3%. The prime age employment-population ratio essentially measures the percent of working-age people who are employed, so it makes for the clearest and most consistent measure of labor market health.

Today’s 78.3% prime age employment-population ratio is nowhere near the pre-pandemic rate of 80.4% or the 2000 record high of 81.9%. Even these numbers are nowhere near the levels of America’s peer nations: Japan currently has an 86.2% prime age employment-population ratio. All this to say that there is still a long road to go before America reaches full employment.

It’s not all bad news, however. The number of people employed part-time for economic reasons dropped to 4.4 million , which is close to pre-pandemic levels. This is down dramatically from the record high of nearly 11 million in April of 2020.

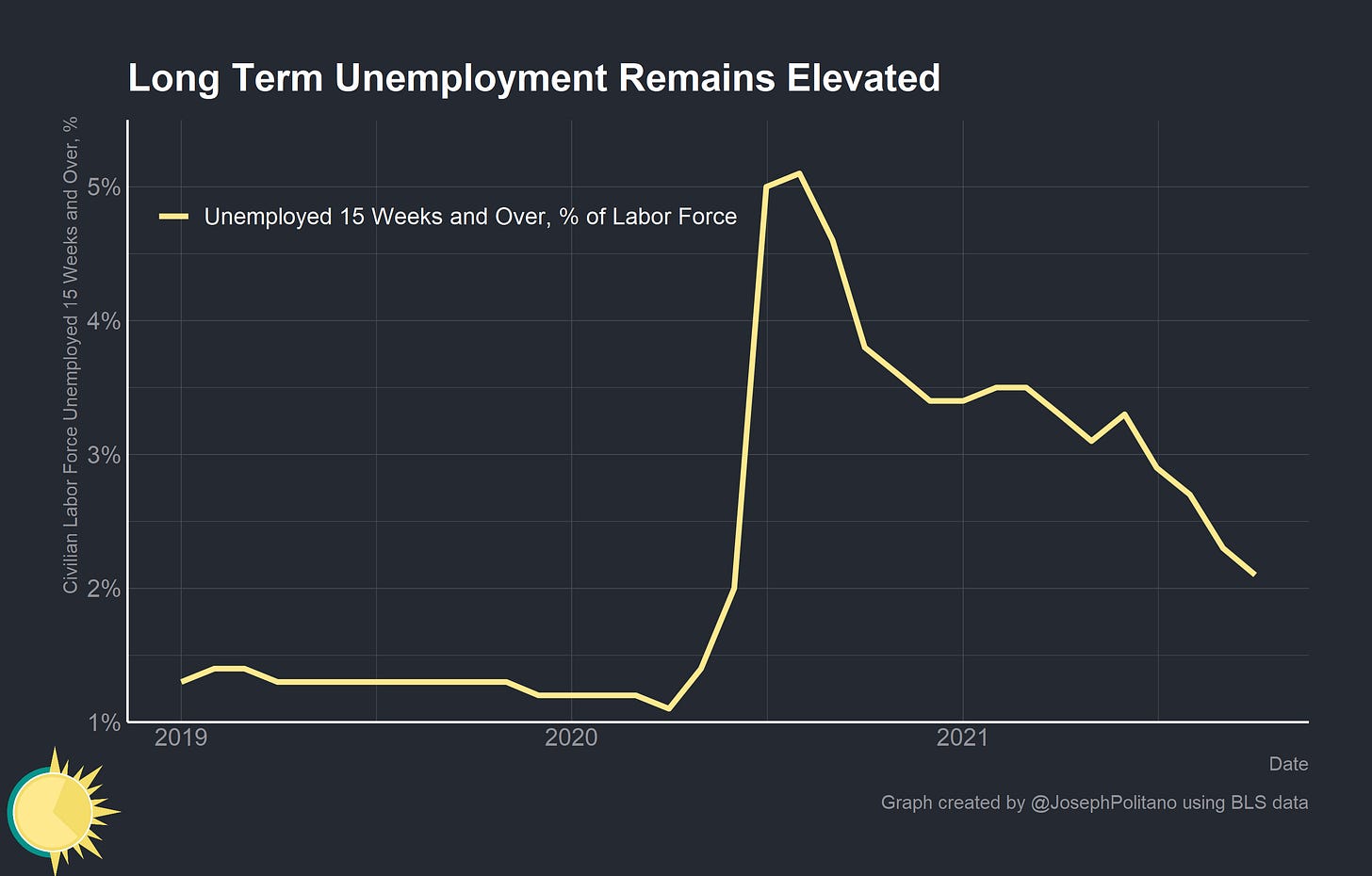

The percent of the workforce experiencing long term unemployment (15 weeks or more) also decreased slightly to 2.1%. Long term unemployment has been on a steady decline since August 2020, when it peaked at 5.1%. Remarkably, despite headline unemployment setting records during the pandemic, long term unemployment never hit the record highs of almost 6% that occurred in 2010. For additional context, the long term unemployment rate did not drop to 2% until 2016, 8 years after the 2008 recession.

Sectoral Breakdown

Digging deeper into the sectoral employment data shows that employment in interpersonal service industries remains depressed while the boom in goods spending has buoyed employment throughout the transportation and warehousing industries.

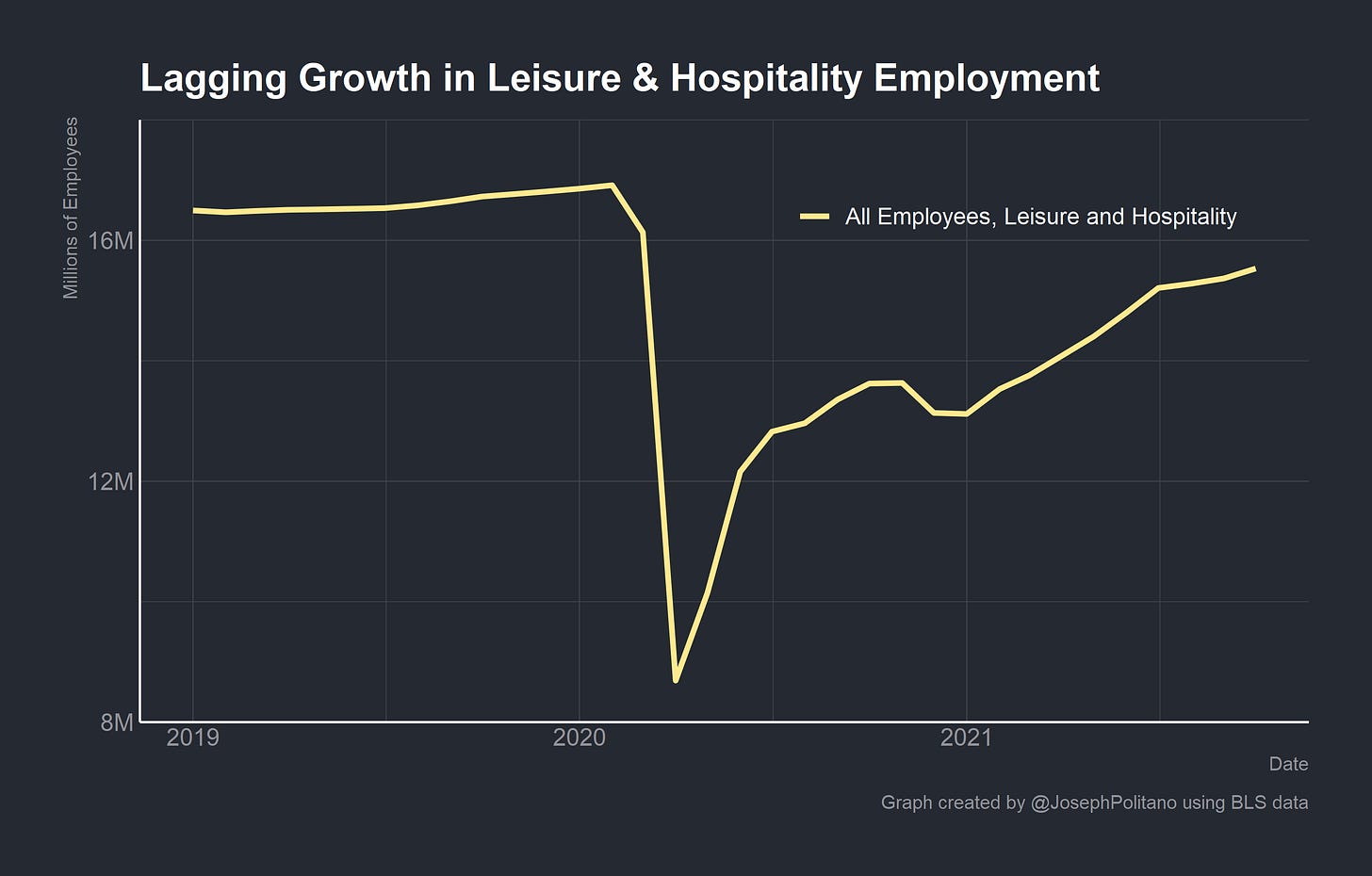

After several months of stagnant growth, the leisure and hospitality sector added 164,000 jobs in October. This is a significant jump but still leaves it far below pre-pandemic levels and a significant laggard compared to the aggregate recovery.

Employment in food services and accommodation, which makes up the majority of employment in leisure and hospitality, jumped up by 142,000. The industry is a long way from the pandemic lows of about 7.5 million, but still more than 1 million jobs short of the pre-pandemic level.

Remarkably, spending on food services and accommodation has recovered and has even exceeded its pre-pandemic levels. In other words, the shift from dine-in to take-out has meant that restaurants and other food service establishments can make the same amount of sales with fewer employees. As the pandemic abates, it will be crucial to see how much of this shift is permanent. 2.6 million people were employed as restaurant wait staff before the pandemic, rivaling the 2.8 million employed by the federal government (this excludes fast-food counter workers, baristas, bartenders, and other consumer-facing food service industry occupations).

Employment in local government education, which is mostly public K-12 schools, is also approximately 600,000 jobs short of its pre-pandemic level. Analyzing the non-seasonally adjusted (NSA) numbers is crucial here, as the seasonal adjustment’s attempts to account for the cyclical decline in school employment over the summer has actually increased the data’s noise during the pandemic. This decline represents an unprecedented hit to educational employment, as employment only decreased by approximately 300,000 in the years after the 2008 recession.

The jump in demand for goods caused by the pandemic has resulted in a miniature boom in the warehousing and transportation industries. A record-high 5.9 million people are employed in the transportation and warehousing industry, with little signs of a hiring slowdown. Employment in warehousing and transportation grew by 54,000 in October. The ecommerce boom of the 2010s has resulted in a long term increase in transportation and warehousing employment from 4.1 million employees in 2010 to 5.9 million today.

While the disproportionate spending on goods will likely subside as the pandemic ends and consumer shift back to spending on services, it is likely that warehousing and transportation employment will continue to reach new highs in the near future. The pandemic has likely accelerated the ecommerce revolution and intensified consumer’s attachments to ordering goods for delivery instead of visiting a store. Employment growth is consistent with the idea of a temporary goods boom but a permanent e-commerce boom—employment in manufacturing has yet to recover as employment in warehousing and transportation continues to grow. Employment in retail trade, which represents the traditional in-person stores, has also not recovered to its pre-pandemic levels.

Conclusions

It’s trite to say at this point, but the pandemic remains the boss of the economic recovery. The primary economic risk this winter remains that seasonal factors will result accelerating COVID-19 case numbers and a decline in possible in-person production and consumption. Only 70% of adults and 60% of all Americans are currently vaccinated, so there is potential for serious disruptions in economic activity if the winter sees another wave of delta variant infections. With so much progress to be made in order to reach full employment, a focus on vaccinations and virus control is critical to further improvements in the employment situation.

Nevertheless, it is worth appreciating the sheer scale of the progress the recovery has made thus far. In less than two years the unemployment rate has dropped from nearly 15% to nearly 4%. It took until nearly 2017 for the prime age employment rate to recover to current levels after the 2008 recession, which speaks to the power of the coordinated fiscal and monetary policy deployed during the pandemic. Things are getting better at a rapid pace, even if there is still plenty of work to be done.

If you liked this post, consider subscribing to get free economics news and analysis delivered to your inbox! Leave a comment below to participate in the discussion or share this post to others who may find it useful!