The Risks Still Lurking in the Banking System

2023 Has Seen the Largest Banking Failures Since the Great Recession—and Markets are Still Pricing in Significant Failure Risks for More Banks

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 28,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

The American banking system is in crisis—three banks with combined assets in excess of half a trillion dollars have failed already, the largest relative yearly total since the Great Recession, and a large number of regional banks remain under intense pressure. What started with the rapid collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank in March led to a swift response from the US government—with the failed institutions declared systemically important and the Federal Reserve shoring up the banking system with hundreds of billions in direct lending—but that has yet to calm the storm. Last weekend, First Republic could limp along no more and collapsed in the second-largest bank failure in US history, and this week saw investors panic that any number of regional lenders could be next.

One way to understand the extent of the damage is to look at market movements for the surviving publicly-traded banks. Year-to-date, the vast majority of banks have negative excess returns—the change in value compared to the overall market average—with most companies sinking more than 25%. A small cohort had dipped more than half, and a select few extremely distressed institutions have fallen as much as 75%.

Who remains at risk? So far, much of the carnage has been concentrated among “mid-sized” or “regional” banks—looking at the returns of publicly-traded banks by asset size shows relatively small declines for the too-big-to-fail titans like JPMorgan or Bank of America and for the nation’s tiniest banks, but significant declines for institutions in the $5-$150B range.

Indeed, several major mid-sized banks have seen their valuations decline 50% or more since the start of the year, being repriced downward in the immediate aftermath of Silicon Valley Bank’s failure and once again in the recent wake of First Republic’s failure. Recent attention has focused on Pacific Western and Western Alliance, smaller regional lenders with $41B and $67B in assets respectively, who faced significant if so far manageable deposit outflows over the last few months, but there are a range of institutions at risk now. Major southeastern lender First Horizon has tumbled after a merger with Canadian TD Bank was called off, Utah-based Zions bank fell amidst slow deposit outflows, commercial bank Comerica has struggled, and even Midwestern commercial and real estate giant KeyBank has gradually declined for weeks. That’s only the major at-risk institutions—smaller banks like Homestreet, First Foundation, and Republic First (not to be confused with the now-defunct First Republic) have all suffered as badly or worse, though they pose less of a threat to the broader financial system by virtue of their smaller size.

These changes in market prices likely reflect several factors—the rapid rise in costs of bank funding, the deterioration of credit conditions in the broader economy, and (most important for this discussion) the elevated probability of bank failure1—but it is also worth noting that share price itself has somewhat of a causal impact on the chance of bank failure via depositor confidence channels. Silicon Valley Bank failed in no small part because well-informed depositors saw the bank’s share price tanking and began withdrawing money out of fear it could collapse, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. Indeed, that appears to be part of the situation for Pacific Western and Western Alliance—this week investors have soured on the banks in anticipation, not in reaction, to possible renewed depositor outflows, and that is likely making it harder for the banks to raise money just when they need it most. Looking at market pricing can therefore illuminate some of the risks still lurking in the banking system—and what could cause other institutions to fail.

Understanding Rates Risk in the Banking System

The Federal Reserve has been raising interest rates for more than a year now in order to combat generationally-high inflation in the wake of the pandemic, and that has put the banking system’s interest rate risks into stark relief. Silicon Valley Bank failed in no small part because it made large, concentrated bets on safe long-term assets at low yields throughout 2020 and 2021, with the majority of those bets concentrated in Treasury bonds, mortgage-backed securities, and other liquid assets. A lot of hay was specifically made about the bank’s held-to-maturity (HTM) securities portfolio—essentially, instead of holding the assets as available-for-sale (AFS) Silicon Valley Bank and many others promised to hold their bonds until they were fully repaid, allowing them to avoid the risk of further mark-to-market losses for accounting purposes. The banking system as a whole has seen the market value of HTM and AFS securities fall by hundreds of billions of dollars since the start of 2022, and the Federal Reserve set up the new Bank Term Funding Program explicitly to allow banks to borrow against their HTM portfolios as if they had not lost value.

However, it would be a mistake to attribute too much of the recent banking crisis to narrow HTM/AFS dynamics—remember that neither Signature nor First Republic had unusually large securities portfolios before they failed, and the at-risk banks today aren’t all necessarily those that made big bets on Treasuries. Indeed, banks’ aggregate losses on their securities portfolios show basically no relationship to market repricing, though a stronger relationship emerges when looking only at HTM losses.

Understanding rates risk in the banking system requires taking a broader view of balance sheets—it is not so much the over-exposure to Treasury Bonds or Mortgage-Backed-Securities per se that markets believe are raising failure risks, but exposure to long-term assets more broadly. Banks with a higher share of their money in 5+ year-long assets have suffered significantly more since the start of this year.

In particular, banks’ real estate lending activities represent another way they had invested in long-term assets that are sensitive to rate hikes—especially now, in the wake of persistent worries surrounding the creditworthiness of borrowers in the commercial real estate lending market. Financial institutions with more real estate exposure have seen worse returns since the start of the year, and America’s small and mid-sized banks tend to have more real estate exposure than its large banks.

Looking at the major at-risk banks, Zions, Western Alliance, and KeyBank all have elevated exposure to long-term assets, though none of them match the long-term asset share of 50% seen at Silicon Valley Bank or the 60% seen at First Republic. All of these banks did, however, also increase their relative exposure to long-term assets over the course of the pandemic.

Aggregate long-term asset exposure in the American banking system remains relatively low though—increasing only slightly from 22 to 25% since 2018. Those assets, to the degree their interest rate risks went unhedged, represent significant unrealized losses. Yet this alone is not enough to cause the recent crisis, and in fact only represents half the picture of the effect of higher rates on the banking system. Talking about banks as if they are necessarily out-and-out losers thanks to rate hikes misses the rise in interest margins over the last year—quarterly net interest income increased by $42B in 2022 as banks charged higher rates for loans and passed on comparatively little to the interest rates paid on deposits. The other ingredient of the recent banking crisis has been the increased risks to banks’ deposit funding.

Rates Risks and The Case of Uninsured Deposits

That risk, at least as currently perceived by markets, hasn’t necessarily come from the flight of deposits to higher-interest assets like money market funds or longer-term bonds. Neither the banks more reliant on noninterest-bearing deposits nor those who used more high-cost time deposits have not been disproportionately punished for it—the narrow effects of rate hikes on deposit costs and flows had mostly been priced in already by the start of the year. Indeed, prior to the recent banking crisis deposit outflows have proceeded at a fairly normal pace and have been concentrated among larger domestic banks.

Instead, it is banks more reliant on uninsured deposits that have seen worse returns since the start of the year. The fall of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic were all caused by the massive, sudden withdrawal of billions in uninsured deposits, and markets are now repricing the renewed information sensitivity of American depositors. It is not entirely that deposits are now unusually sensitive to interest rates and moving quickly to seek yield, but rather that banks with significant losses thanks to interest rate movements are finding their depositors much more sensitive to questions of solvency and liquidity.

Of the six major at-risk banks, most rely on uninsured deposits for a significant chunk of their funding—though none to anything approaching the degree of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, or even First Republic. Pacific Western and Western Alliance have already seen some flight of uninsured deposits in the wake of SVB’s failure, though reportedly little yet in the wake of First Republic’s failure.

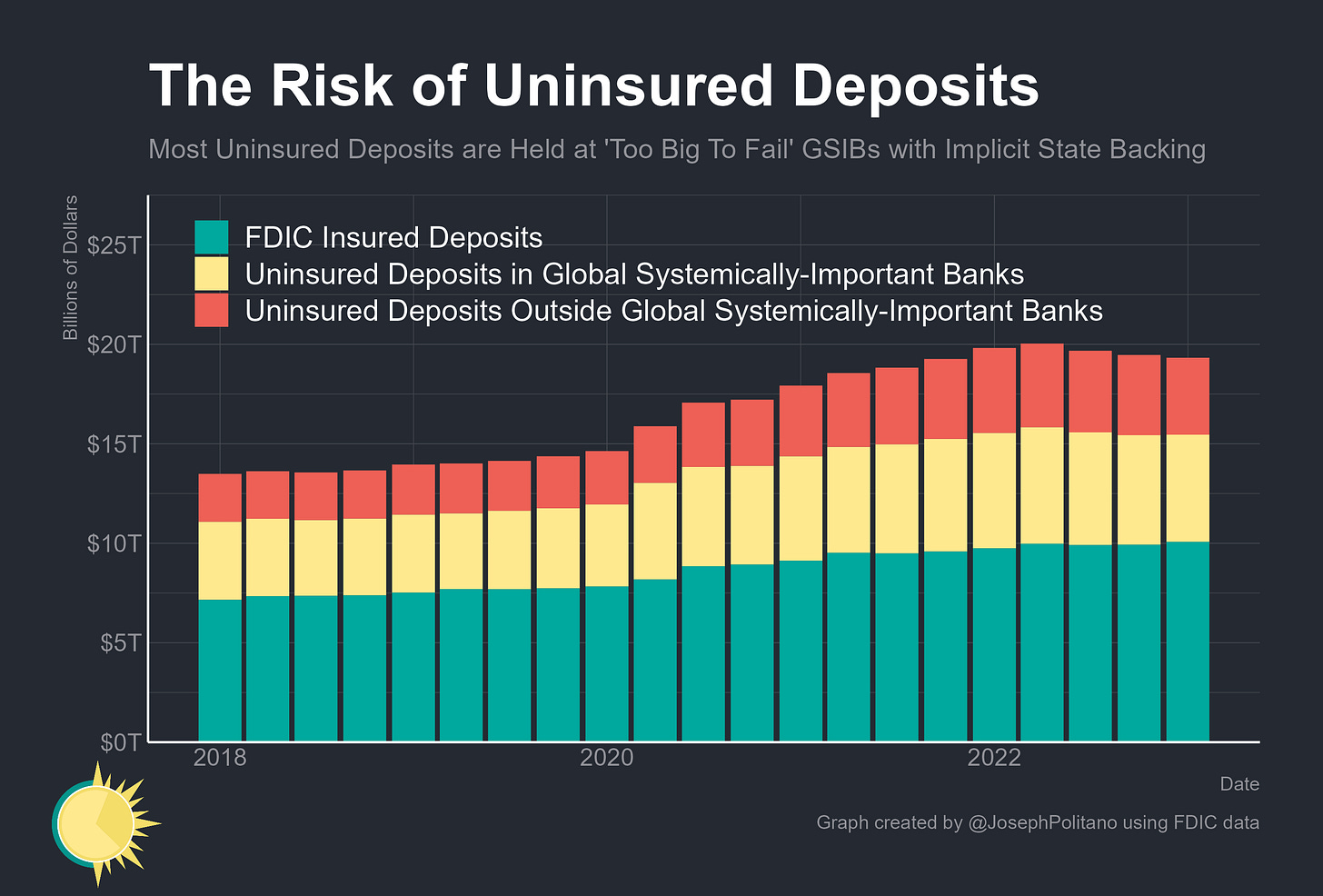

The renewed concern about nominally uninsured deposits is, to a degree, a strange phenomenon since the vast majority of American deposits have government backing—about half are FDIC-insured, and another large chunk are held at Global Systemically-Important Banks (GSIBs) that are essentially government-backed by virtue of being explicitly regulated as too-big-to-fail. Plus, the US government has implicitly backed all domestic deposits, whether officially insured or uninsured, since the 2008 crisis, and declared all the recently-failed banks systemically important in order to ensure their depositors were all made whole. Given the great lengths undertaken in backing deposits, one would not expect markets to be so apprehensive about more bank runs by uninsured depositors.

Plainly, it’s clear that government efforts haven’t yet been enough to convince depositors their money is safe. The government backing of uninsured deposits at Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank did not convince First Republic’s depositors their bank was safe, and in related crises abroad even GSIB status did not stop Credit Suisse’s depositors from fleeing. To the extent depositors remain unconvinced of the financial system’s safety and security, banks with shaky balance sheets reliant on uninsured deposits will continue to be punished.

Cooling the Crisis

The good news is that, after the failure of First Republic, it looks as though relatively few financial institutions currently have highly acute funding stresses—Federal Reserve direct lending to banks via the discount window fell to a post-SVB low last week. Aggregate bank borrowings had stabilized about $100B below March highs in the week before First Republic’s failure, with borrowings at small domestic banks falling 20% from peak levels.

Deposit outflows also seem to have slowed down for the time being, especially at the smaller domestic banks that saw rapid outflows in March. The recent stock market turbulence therefore seemingly reflects anticipation, not reaction, to banking risks—jitters about the possibilities of future deposit outflows rather than reactions to current withdrawal behavior. Those jitters, however, have continued to intensify over the last few weeks and have spread to institutions that, while smaller, should have been less susceptible to failure than the crisis’ prior victims. The underlying risks of flighty uninsured deposits and a banking system with large unrealized losses on long-term assets haven’t changed, and the crisis won’t fade completely until confidence is restored and banks have enough time to fully adapt to the new macro environment.

Looking at stock returns is perhaps the best way we have for gauging the risk re-pricing of banks amidst the current crisis, but it is by no means perfect. Prices can be volatile and move with liquidity and sentiment just as often as with fundamentals. Many stocks—like Citi or Charles Schwab, for example—are not simply holding companies for commercial banks but encompass multiple business ventures like asset management or investment banking and are influenced by factors besides changes to the banks’ valuation. Publicly-traded financial institutions may have different profiles to the unobservable valuations of private banks, and as always correlation does not necessarily mean causation. It’s important to keep these in mind when discussing pricing, but it’s also true that structural shifts in risk pricing could also be reflected in changes in publicly-traded asset prices.

A special thanks to Paul Goldsmith-Pinkham, whose work and assistance were essential to the excess returns analysis in this piece.

Love the visuals Joseph!

Fantastic post.

Banks will get par back on their bond portfolios. Need enough capital to see the maturity payback!

Most depositors should be indifferent if their bank fails.

IRR / ALM management is banking 101. Those that don’t know this deserve failure.

Banks will earn less until/if/when curve normalizes. Again, need enough capital to wait for this!