The Semiconductor Trade War

The US is Engaged in a Massive Chip Trade War with China. It Will Need Help if It Wants to Win

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 29,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

The last decade has been dominated by the partial unraveling of global trade networks amidst growing great power competition. The world’s major democracies, finding themselves facing down aggressive autocratic states in China and Russia, have stopped believing in the power of trade to induce political liberalization and international friendship. The result has been the growing use of economic conflict and industrial statecraft to achieve geopolitical aims—and an increasing frequency of trade wars. This was particularly important in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, where a package of harsh financial and trade sanctions from the US, EU, and others threw Russia into a recession that helped reduced its war-making capabilities. Yet the Russian trade war pales in size and technological importance to another economic conflict—the American-led semiconductor trade war with China.

Semiconductors are among the most complex products ever developed by humanity. They are essential components to the production of all modern manufactured goods—as Western countries learned when the chip shortage of the last few years crippled production in key industries like motor vehicles. They are necessary for the training and implementation of large-scale, cutting-edge Artificial Intelligences like ChatGPT, which are poised to play an increasingly large economic role in modern life. Of course, they are also critical components of the kinds of modern military craft and advanced weaponry the major democratic allies use to defend themselves and countries like Ukraine. China has long resented its technological dependence on foreign chips—which often make up a larger share of the nation’s total imports than oil—especially since so much of its foreign chip imports come from Taiwan, whose independence China does not respect. Western countries likewise fear that China will continue moving up value chains, build a threatening lead in high-end chip production, and gain even more economic leverage over the rest of the world.

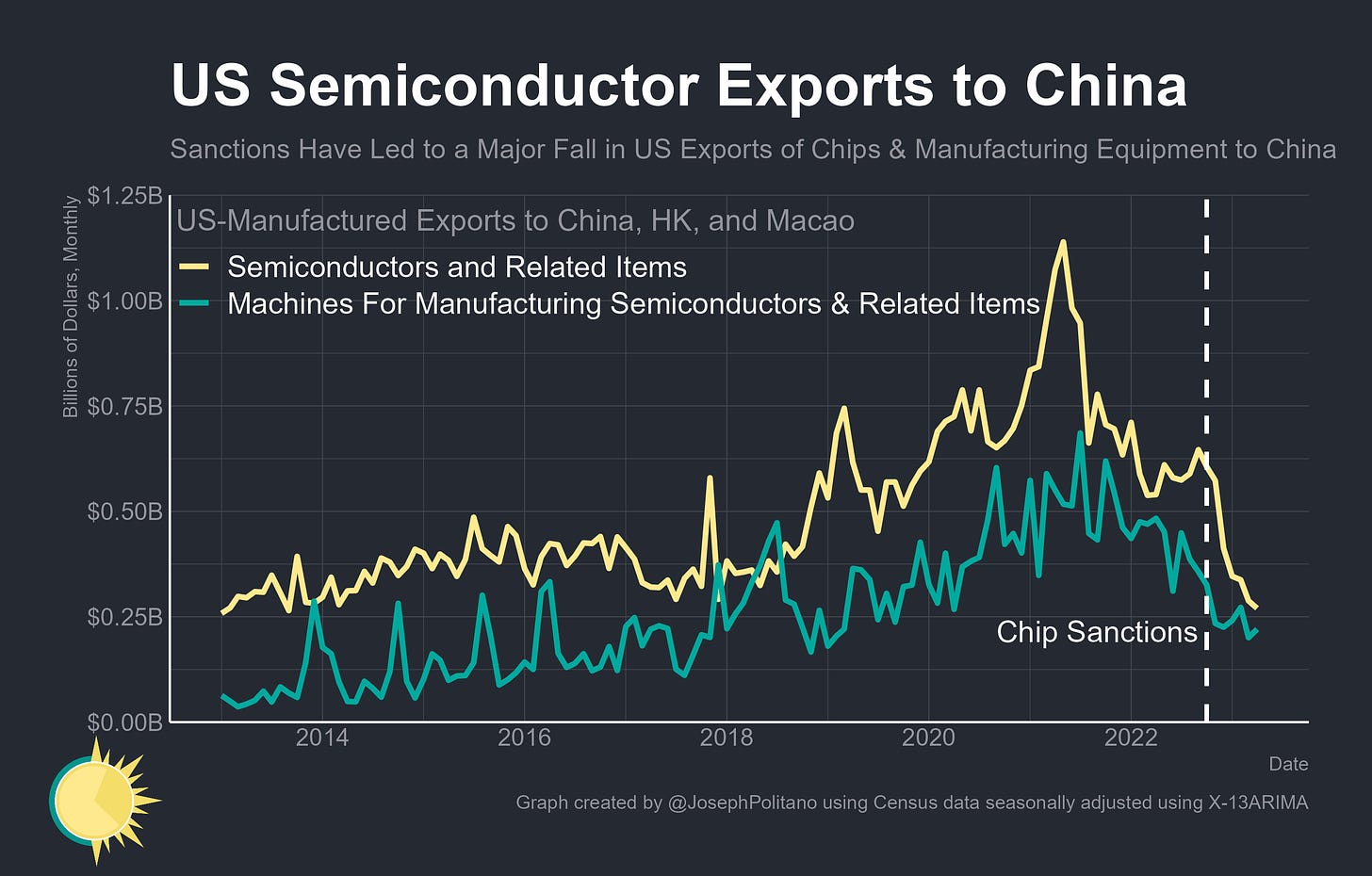

That’s why the Biden administration announced a comprehensive package of chip sanctions and export controls against China back in October 2022. The sanctions are designed to restrict US exports of advanced chips and chipmaking equipment to China, curtail exports from non-American nations that use US tech, and even restrict US citizens or green card holders from working at Chinese semiconductor production facilities. The implementation of those sanctions has caused US-manufactured chip exports to China to fall by nearly 60% since September and exports of US-manufactured chipmaking equipment to fall by nearly 40%.

However, the US will need high levels of help and coordination from Allies and trade partners, especially in Asia, to have any hope of winning this trade war. While most of the world’s largest semiconductor companies are still American, the vast majority of semiconductor fabrication and equipment manufacturing occurs abroad, and chip supply chains are the most complex to ever exist. That level of coordination is a tall task—the EU has been hesitant to take a strong stance in the US-China trade war that has been ongoing since 2016, and countries like Japan and South Korea have recently leveraged the semiconductor industry in fights amongst themselves. The situation is not helped by the fact that US industrial policy, while primarily about competition with China, is also unsubtly trying to wrest control of chip supply chains from America’s Asian and European allies, and is predictably drawing pushback from those nations. The task of coordinating the chip sanctions is especially daunting given the global semiconductor market has entered a short-term downturn as the shortages of the last three years turn into gluts. Given that most of the world’s chip exporters currently sit on shakier macroeconomic ground than the US, it will be harder to convince them to endure short-term economic pain in order to slow China’s semiconductor industry.

Now is still, perhaps, the best opportunity for the US to strike. China’s manufacturing industry is slowing down from the boisterous pace seen during most of the pandemic, the US still maintains a significant lead in AI development, American companies still dominate global semiconductor sales, and the CHIPS Act has mobilized significant government resources toward building up domestic semiconductor supply chains. That money can hopefully smooth over some of the short-term costs that the trade war will have on America’s allies while building a domestic production base to compete directly with China—giving the US the strategic option to ban foreign equipment exports to China and scoop up the equipment for itself. That does not mean the trade war will be easy, however—semiconductor smuggling is a serious problem, as we’ve seen in enforcing sanctions against Russia, Chinese entities will likely attempt to circumvent sanctions by renting usage of restricted chips through cloud providers, and the Chinese government is likely to respond with an escalation of counter-sanctions and subsidies in order to build up its domestic semiconductor manufacturing capacity. Indeed, China has already banned imports from major US chipmaker Micron from being used in key infrastructure projects and is looking to hurt foreign semiconductor producers by restricting exports of certain chip input minerals and materials. The semiconductor trade war is now in full swing—and it will forever reshape the future of the global economy.

The Trade War

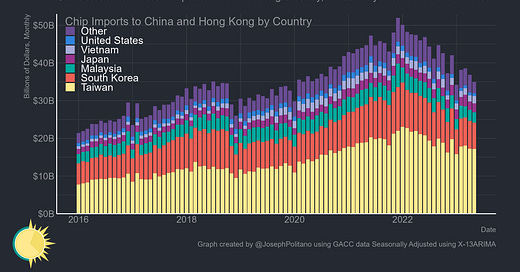

Right now, Chinese semiconductor imports have fallen roughly 30% from their early-2022 highs and are notching levels not seen since before the pandemic thanks to a combination of sanctions and waning electronics demand. The decline has been led by a fall in imports from major East-Asian chip producers Taiwan and South Korea—the PRC’s largest suppliers. Perhaps most importantly, it’s worth noting that the US makes up an extremely small share of total Chinese chip imports. America does punch above its weight—its exports are disproportionately high-cost high-end logic chips, but its fabricators still play a small picture in the overall Chinese supply chain, underscoring the need for cooperation from foreign fabricators of American firms and other foreign non-Chinese companies.

Taiwan, home of TSMC and the site of the vast majority of the world’s cutting-edge chip production, has seen a roughly 20% fall in the value of its semiconductor exports to China since the start of 2022. The country was reportedly on board with Washington’s sanctions from the get-go, eager to reinforce its “silicon shield” and maintain China’s dependence on its chip foundries. Yet the US is having a harder time getting countries like South Korea on board, given the country is a major supplier of Chinese chip imports and is also building out fabricator capacity within China. Still, top chipmakers from both South Korea and Taiwan have been recently granted waivers by the US to expand production in China.

Semiconductor manufacturing equipment imports—arguably more important for China’s efforts at building a domestic manufacturing base than the chips themselves—have likewise fallen significantly from their early-2022 highs. Here is where the US also has significantly more leverage—America was the second-largest source of Chinese chip equipment imports in 2021, and its exports have shrunk dramatically over the last year. It is Japan, however, that remains the predominant supplier of Chinese semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

Japanese semiconductor equipment exports to China have declined from their 2021 highs over the last year, but remain about on par with pre-pandemic levels. However, the Japanese government has recently announced export restrictions on 23 types of semiconductor equipment, widely recognized as a move to curb China’s access. Those sanctions take effect this month, meaning Japanese equipment exports to China could shrink further going forward. The Netherlands, home of ASML, the world’s leading producer of photolithography equipment for chip production, has likewise announced a series of export restrictions aimed at China that are set to take effect this September.

China’s Semiconductor Industry

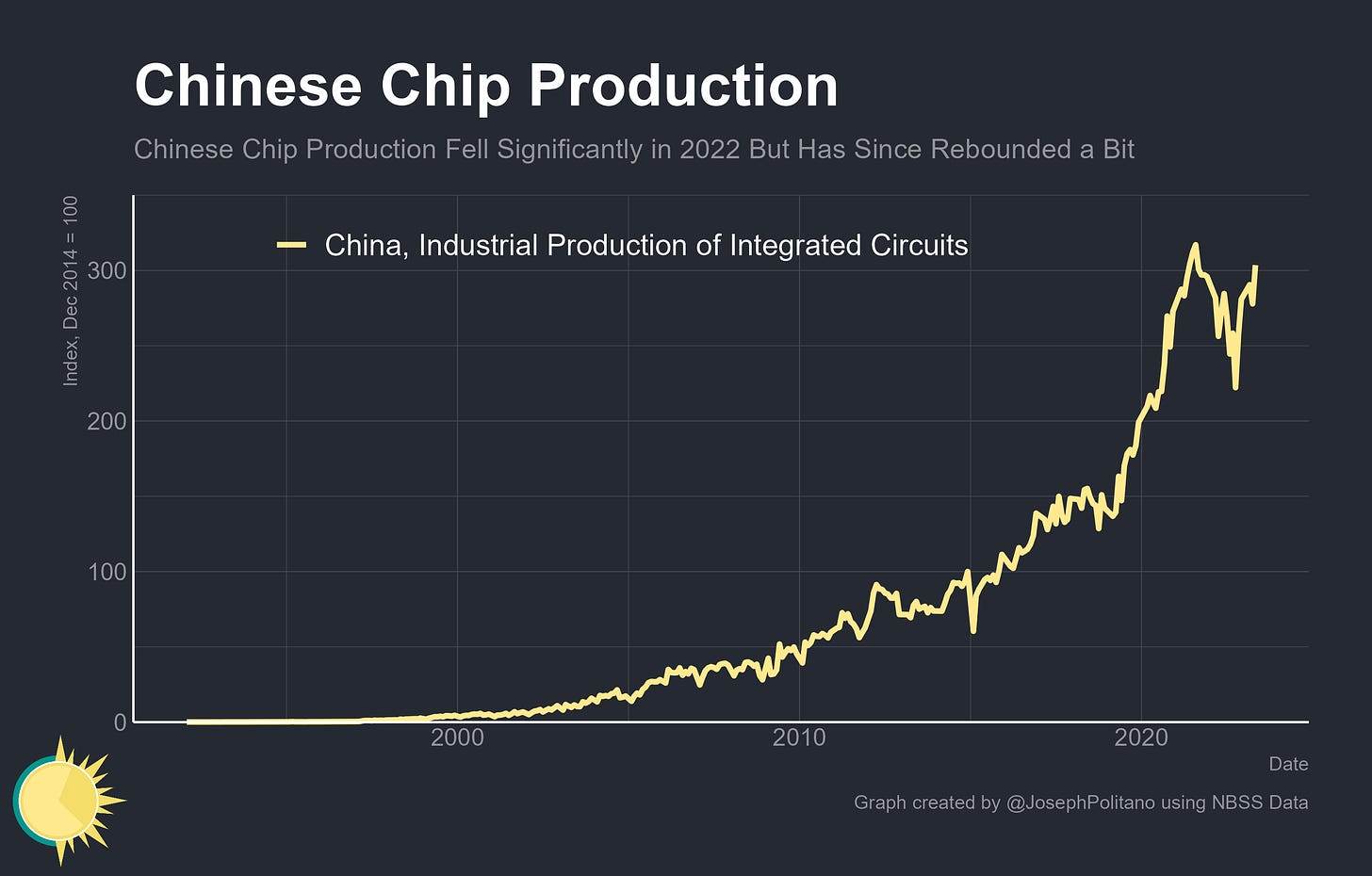

Still, domestic Chinese chip production is near all-time highs despite the sanctions—and has grown significantly during the pandemic. The PRC’s rapid export-oriented industrialization and high economic growth over the past three decades have led to sustained growth in semiconductor output, even if the country remains behind the technological frontier. Recent years have been a massive boon to the industry—Chinese integrated circuits production practically doubled during the pandemic before declining during the country’s 2022 slowdown, but has since recovered significantly.

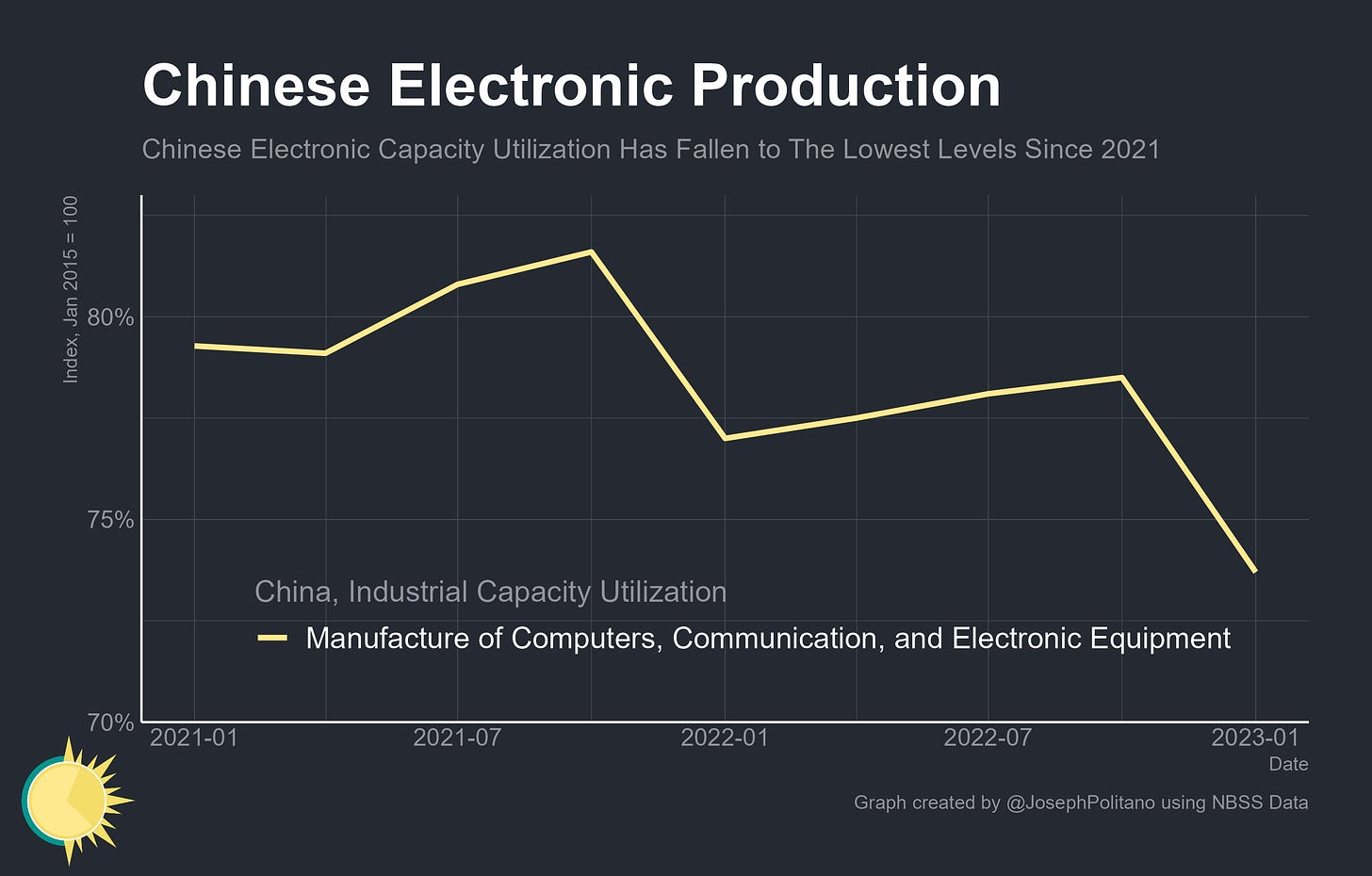

Sanctions, however, have likely already put some pressure on Chinese electronics output. The share of computers, communication, and electronics manufacturing capacity being utilized in active production dipped to the lowest level in the data’s two-year history at the start of 2023.

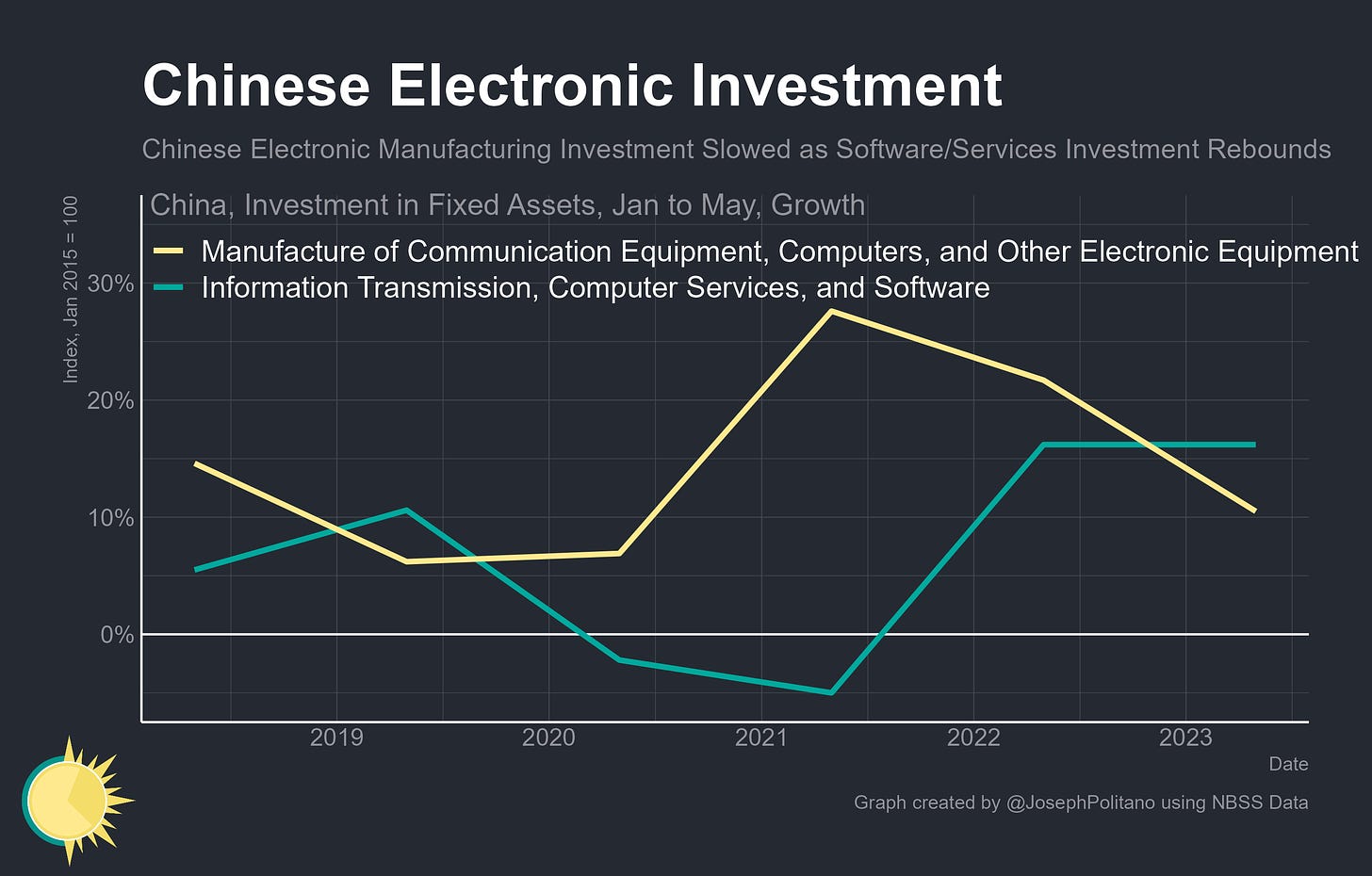

Growth in Chinese fixed investment for computer and electronics manufacturing has likewise slowed significantly from the pandemic-era boom, though it remains rapid by international standards. On the flip side, growth in computer services and software investment, hampered by the CCP’s crackdown on tech companies throughout the last few years, has now rebounded significantly as the country tries to catch up on artificial intelligence and other digital industries. However, part of what makes analyzing the direct impact of the sanctions hard—besides the general unreliability of Chinese government data—is that large parts of the global semiconductor market have contracted recently as chip shortages get resolved and demand for certain end-use technology goods shrinks.

The Chip Wreck

The last three years have seen a nearly-unprecedented boom in global semiconductor production that was still not enough to keep up with the surge in demand—leading to persistent shortages of chips and other electronic components. Those shortages are not completely over, with many specialty chips still in short supply and some electronics makers still complaining about input backlogs, but in a wider sense, global supply has more than caught up with falling global demand. The price of South Korean semiconductor exports—which bias towards more commodified memory chips—has fallen more than 40% over the last year, though the recent focus on AI has led to a surge in demand for select high-end logic chips.

The weakness in the chip market, waning demand for consumer electronics, and the slowdown in China’s economy have led to a dramatic fall in semiconductor production across key East Asian producers. Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan have all seen production fall by between 15% and 25% since this time last year—enough to erase much of the output boom seen during the pandemic.

The recent market glut has crimped semiconductor output across the world, but especially in the markets that benefitted the most from the pandemic. Output in Taiwan has cratered to the lowest level since early 2020, Korean production had fallen to the lowest level since 2019 before a recent rebound, and production in Japan has shrunk back to 2021 levels. However, output in the EU and US—which admittedly do not have data to the same level of specificity as the major East Asian producers—have held up relatively better, likely thanks to the lower overall level of production, concentration in high-end chips, and increase in government support for the chip industry.

However, output in the semiconductor equipment market remains strong despite the dramatic fall in chip production. Aside from Japan, most countries don’t produce data on semiconductor manufacturing equipment production directly, but the broader data we do have from Taiwan and the Netherlands corroborates the Japanese data in showing a sustained boom with only a slight slowdown this year. Likewise, American data on semiconductor equipment prices shows record-setting price growth approaching 9.5% over the last year, in stark contrast to the falling prices for chips themselves.

The CHIPS Act and Opportunity

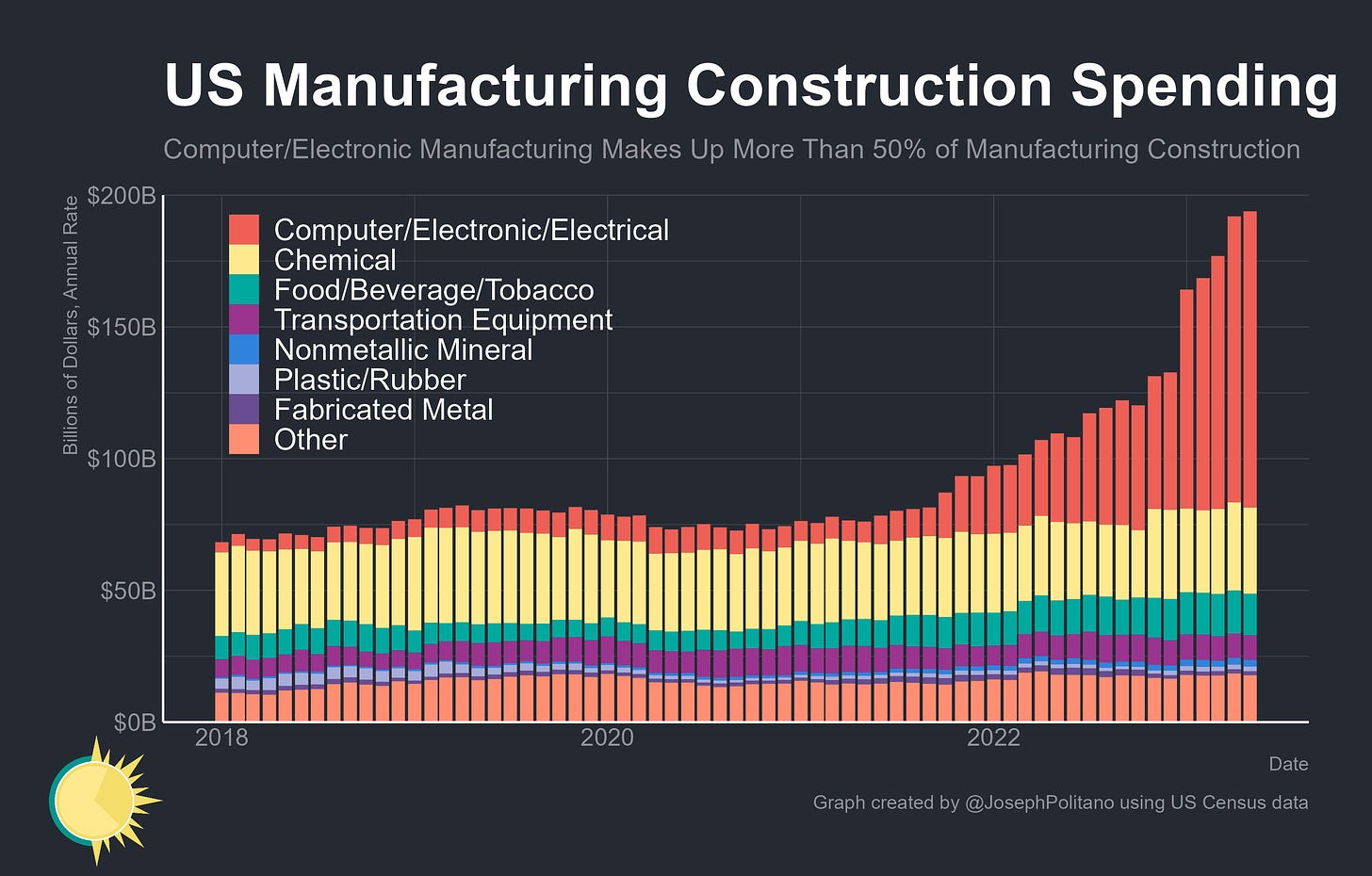

Meanwhile, the pace of US domestic semiconductor manufacturing construction continues to accelerate, thanks in large part to the CHIPS Act and Inflation Reduction Act passed last year. Nominal spending on manufacturing structures notched another new record high in May, with nearly 60% of that coming from the construction of computer and electronics manufacturing facilities in the American southwest.

That boom in domestic US chipmaking construction has been coupled with rising demand for semiconductor equipment that can’t be met domestically. The pace of US semiconductor equipment imports over the last few months has been near an all-time high, with Japan, the EU, and Singapore being the major sources. This is part of the reason why the market for semiconductor equipment hasn’t contracted alongside the market for chips themselves—propelled by the desire to build resilience in chip supply chains post-pandemic, countries like the US have been investing billions to supplement the already-large investment budgets of private chipmakers.

Indeed, domestic US business investment in “special industry machinery, n.e.c.”—a category that mostly reflects semiconductor machinery and equipment—had doubled in nominal terms since mid-2020. Even on an inflation-adjusted basis, annual investment is 50% higher than at the prior peak in 2019. That supercharged domestic investment is perhaps the US’ greatest asset in the current trade war—buying up scarce chipmaking equipment will leave less available for China, and the spending downstream of the CHIPS Act gives America leverage to encourage compliance among its would-be customers and trade partners.

A New Era of Industrial Trade Policy

The story of the US-China trade war from 2016 to 2023 has been one of almost-continuous escalation—the at-the-time unprecedented Trump administration sanctions on Huawei now look minor in comparison to the current package of sanctions being leveled against China. Indeed, the Chinese trade war is a rare source of agreement between Democrats and Republicans and the single largest policy continuity between the Biden and Trump presidencies. Further escalation looks extremely likely, especially if the current bout of sanctions proves ineffective or China continues attempting to retaliate back.

Gaining a relative advantage in semiconductor fabrication will be difficult for the US—rebuilding the domestic industry nearly-whole-cloth will require an industrial policy success that America has not been able to replicate in decades—but trying to hamper Chinese production without catching up domestically won’t work long-term. Likewise, the US has no hope of winning this trade war alone, especially considering how much global capacity and expertise is included outside the country. Given that America’s European and Asian allies are also looking to spend billions to boost their own semiconductor industries, it would be better for all if more of this money was spent on interconnected friend-shoring instead of squandered on trying to one-up democratic trade partners. Here is where the US has a novel opportunity as the strongest of the democratic economies to manage the demand-side policy—the government can indirectly return to its Cold War role as the marginal buyer of select chips and equipment to guide international markets and push along domestic production.

Yet the attempted untangling of global trade networks and the increasingly closed economic stance of major economic powers all have costs—nations are accepting a reduction in efficiency and economies of scale to achieve more security and are plowing money into fixed investments to build out redundant capacity to build out resiliency. All of that contributes further to short-term inflationary pressures, and, to the extent that great power economic conflict continues escalating, additional hits to prices and productivity can be expected. Whether America wins the chip war after paying those costs—and regains the economic security it desires—remains to be seen.

Thanks for the fantastic writeup Joey!

Great piece!