The State of Russia's Wartime Economy

Russia's Economy is Recovering From Western Sanctions—But the Cost of the War Itself is Growing

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 33,000 people who read Apricitas weekly

It has now been nearly a year and a half since the Russian military invaded Ukraine, kicking off the largest European war in a generation and one of the largest refugee crises in human history, and since then the conflict has grown to impose a considerable cost on Russia’s economy. The initial impact of sanctions from the world’s major Democratic Allies threw the Russian economy into a recession, the subsequent loss of key material imports crushed Russian complex manufacturing, and the gradual decline in energy prices throughout late 2022 and early 2023 has begun depriving the Russian state of revenue. The situation on the battlefield and at home had degraded so much that mercenaries from the infamous Wagner group launched a failed rebellion just over a month and a half ago.

Yet, from a broad perspective, the Russian economy has proved more resilient than expected in the face of these shocks. To the extent you can trust Russian data, the GDP loss caused by sanctions—while still on the caliber of a major recession—looks to be fading as the economy recovers. A higher-frequency real output index points to stronger growth in this quarter and the last, outside of the weakness in the oil and gas sector. Russian manufacturing output also continues to recover from 2022 lows, and consumer spending has returned back to late-2021 levels despite the surge in inflation last year. Russia has become a lot more dependent on Chinese imports and financing to achieve this, and will still likely end the year with negative growth if a recovery in energy doesn’t materialize, but the forecasts of economic catastrophe have been avoided.

Thus, Russia’s wartime economy is entering a new phase—one where the country is trying to meet the rapidly growing costs of the war while its economic growth rate remains slow. Ever more resources are being directed away from the Russian civilian economy and toward the Russian military, the results of which are persistent government borrowing to fund the ongoing invasion and growing labor shortages as workers get pulled to the front or leave the country altogether. Russia is also becoming more geopolitically dependent on China, with the post-invasion economic resiliency and de-dollarization efforts mostly resulting in poor terms of trade with China and deepening financial bonds between the two countries. Right now, the costs of the war are growing faster than Russia’s economy, and without changes on the battlefield that will likely require mean squeezing of Russia’s civilian economy.

Russia’s Slow Industrial Recovery

The most important aim of the original sanctions against Russia was to cut them off from key manufactured imports in order to damage their war-making capabilities specifically and their economy more broadly. That would buy Ukrainians time to build up defenses, reduce the total potential damage Russia could inflict, and drive up the cost of continuing the war. On the first metric, the sanctions were somewhat successful—the economic slowdown Russia suffered in 2022 limited its ability to make and hold territorial gains. Yet Russian manufacturing is now recovering from the initial shock, with the share of factories idled by materials shortages falling back to just above prewar levels.

Still, despite the easing of some of the sanctions-caused supply constraints, real output in both manufacturing (which includes oil refining) and mining (which includes oil and gas extraction) remains below pre-invasion levels. In mining’s case, the downturn is particularly acute thanks to falling global oil prices over the last year, the cutting of Nordstream and other natural gas pipeline networks to Europe, and the marginal effects of price caps on Russian oil. Manufacturing, however, is more relevant to the war effort itself—the ability to produce more weapons, ammo, trucks, and planes while satiating consumer demand was always going to be the limiting factor for Russia’s military before energy commodities—and its overall output is slowly recovering from the effects of sanctions.

Yet despite the partial recovery in broad manufacturing, sanctions are still having effects on key subsectors of the Russian economy, especially high-complexity durable goods for the civilian sector. The manufacture of Russian motor vehicles fell by 60% in the immediate aftermath of the recovery and has only started recovering, and a similar but less extreme version of that story has also played out with household appliances like washers and stoves. Costs for many of these household durables have surged, with prices for imported new cars up 60%, and prices for domestic or used cars up 30% since January 2022. However, there has been some recovery in vehicle, appliance, and machinery manufacturing in early 2023, indicating that sanctions are even losing some of their bite here.

On the flip side, high-complexity manufacturing resources have been partially redirected away from the production of many consumer-grade items towards additional military manufacturing—alongside replacements for lost imports. Output for electronic and electrical products has risen significantly since the start of the invasion, as have the broader categories that include defense vehicles.

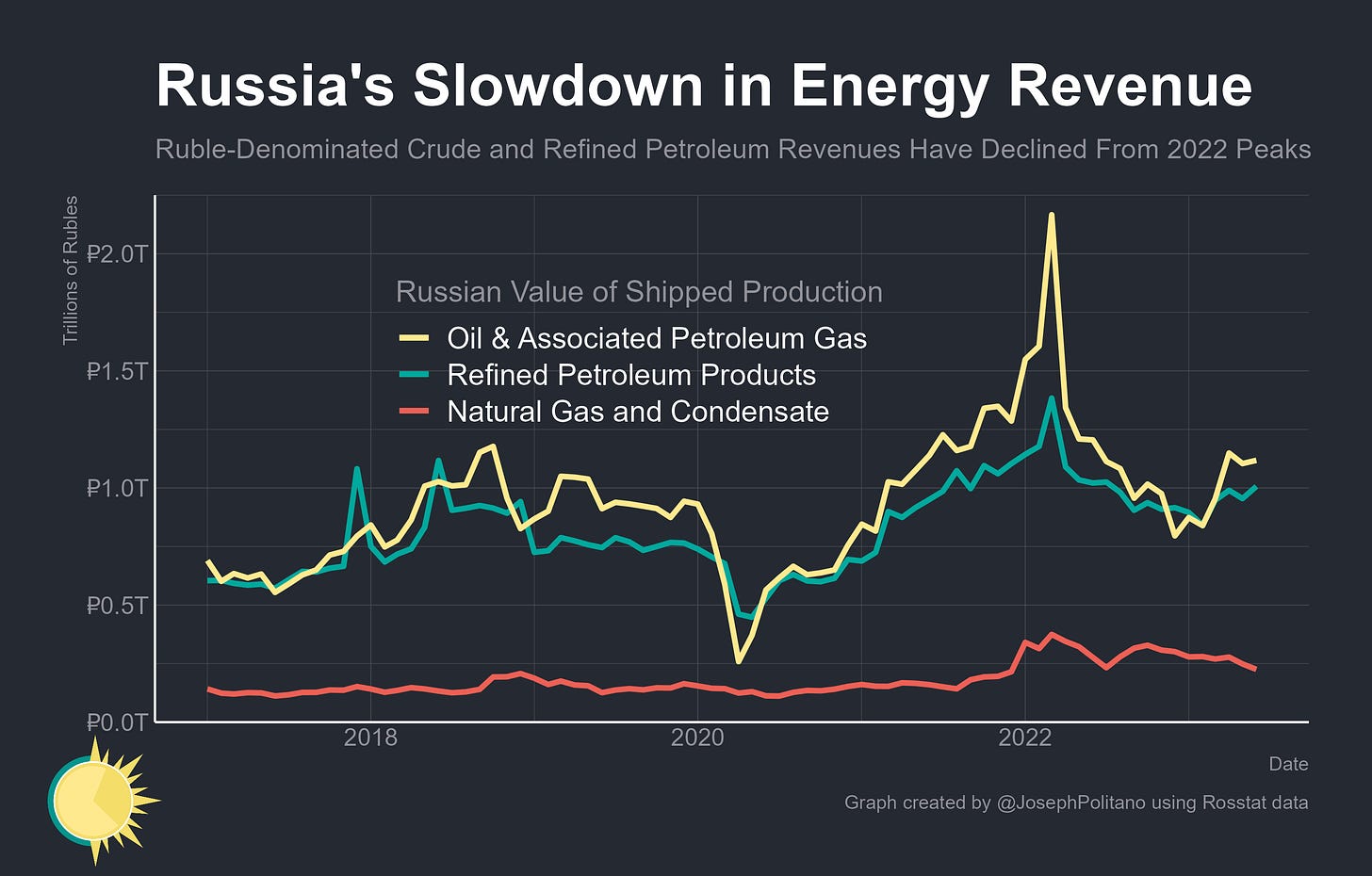

Raw materials output is a bit trickier to analyze, as Russia has recently stopped publishing many official oil and gas output statistics—something they have done before with trade and government spending data when those numbers looked unfavorable. However, we can still look at the nominal value of energy commodity shipments to get a feel for the state of the industry. Nominal ruble-denominated shipments of oil and refined petroleum products fell to pre-pandemic levels in early 2022 before rebounding, while the value of natural gas shipments are now at the lowest levels since late 2021.

The end result is that monthly government revenues from the oil and gas sector fell to the lowest levels since 2020 this June and were down 45% from 2022 throughout the first half of this year. That does not translate into increases and decreases in military capabilities as directly as reduced imports and manufacturing capacity do, but it represents another factor that makes the costs of Russia’s offensive operations harder to bear.

Russia’s Growing Recoupling with China

A large proximate cause for the resurgence in domestic Russian manufacturing output has been the surge in imports—over the last year, the tight grip that Allied countries had over goods inflow into Russia has weakened considerably, allowing the country to pull in essential equipment and intermediate goods to strengthen its industrial base. Those rising imports, combined with the decline in exports as the energy crisis eases, have meant that Russia’s goods trade surplus is once again below pre-pandemic levels, and by far the largest source of these new imports is Russia’s surging trade with China.

When Russian car manufacturing was crippled by sanctions it was China that stepped in to replace the lost production with imports—and that pattern has repeated across a variety of industries. China has rapidly risen to compose nearly 40% of total Russian imports, practically double peak pre-pandemic levels. The largest single category is passenger vehicles, but China is also exporting massive amounts of excavators, front-loaders, diesel trucks, and other industrial equipment alongside large amounts of electronics like laptops, smartphones, and televisions. China is making a pretty penny off those sales—especially important given their slowing economy—and is also getting access to energy goods slightly below global market rates while building up greater financial involvement within Russia’s economy.

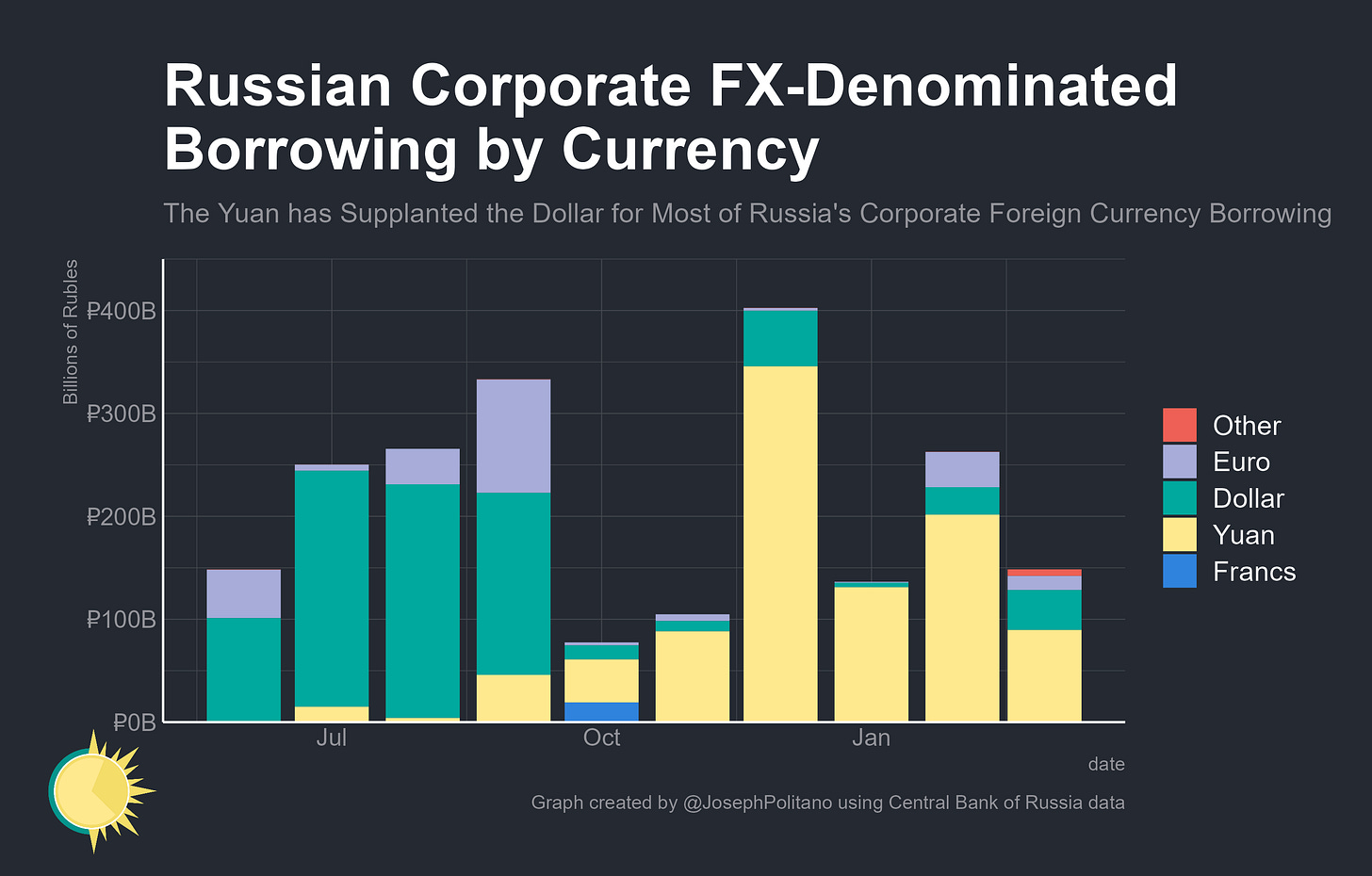

Indeed, Russia has also attempted to reduce the usage of what it calls “toxic” currencies—particularly the Euro and Dollar, but in practice that has mostly meant increasing its dependence on the Chinese Yuan. It has now firmly supplanted the Dollar as the source of most Russian firms’ foreign-currency financing needs—although the amount of aggregate foreign-currency borrowing is also decreasing.

As part of this policy, Russia has also tried to push for the use of the Ruble and other nontoxic currencies for more of its international trade settlement. Newly released data—the publication of which was suspended by Russia throughout much of the early invasion, likely for looking unfavorable—shows that so far they have had extremely limited success in using the Ruble to purchase goods and services abroad. Few countries want to or can take it, with the growth in Yuan usage for Chinese imports primarily responsible for supplanting Dollar and Euro usage.

Russia has had more success in getting countries to pay for Russian exports using the Ruble, invoices for which have essentially doubled in aggregate from this time last year. The Yuan, however, is again the major story here, going from a minuscule share of Russian export payments to the second-largest currency used within the span of a year. Indeed, Russia’s de-dollarization should arguably be understood as growing dependence on China—of which the use of the Yuan is a secondary part. The principal dynamic of the relationship is that China gets a place to sell extremely large numbers of goods to externally at a time when the country’s domestic demand is still extremely depressed, and Russia gets somewhere that is not as sanction-hit where it can outsource production of much-needed physical goods. In that way, decoupling from the West has served to concentrate Russia’s geopolitical risks, not diversify them, and has made Russia’s position more fragile—another major cost of the conflict.

The Growing Costs of Russia’s War

The item within the Russian Consumer Price Index with the single-largest increase since the start of 2022 is, perhaps surprisingly, vacation trips to Turkey. That reflects a lot of factors—higher fuels costs, a weakening Ruble, and more restricted travel, but it also reflects a core truth: Russians are leaving the country in large numbers post-invasion, as evidenced by exit transportation demand and the movements of large amounts of financial assets out of the country. That exodus, combined with the growing demand for military personnel as the war intensifies, is sparking persistent labor shortages in Russia.

Talk of labor shortages in countries like the US usually simply means that the economy is running at a fast pace, higher-wage jobs are poaching workers from lower-wage jobs, and institutions are greatly incentivized to make labor-saving investments. But that wage-led growth process relies, in large part, on gains from investment and growth in high-productivity sectors. In other words, if manufacturing labor is in short supply because workers are easily able to get higher-paying white-collar opportunities, that’s likely a good sign for workers and the long-term trajectory of the economy. Yet if manufacturing labor is in short supply because the would-be workers are off fighting expensive wars abroad, that’s a massive economic productivity downgrade that is borne mostly as losses from the civilian sector. Likewise, net emigration is usually good for countries as most emigres will return intermittently and reinvest their wages, knowledge, and assets back into their country of birth—but the long-term exodus of many high-income workers seeking to more permanently leave, as we have seen in Russia, presents a serious problem.

In aggregate, the Russian economy is recovering and has survived the initial wave of sanctions, but as the war continues to escalate it is becoming a larger draw on Russia’s limited pool of economic resources. Defense spending in the first half of this year is rumored to approach $60B—a figure 12% above its full-year 2023 targets—and aggregate official government spending as a share of GDP is surging to new highs. In documents seen by Reuters, Russia now expects to spend more than $100B on the war throughout this year—for context, that would be roughly 5% of GDP spent on the military. Meanwhile, Allied countries have been able to mobilize roughly $90B in direct military equipment assistance alone—at a time when Russia’s government budget deficit is at some of the highest levels since the turn of the century.

Yet even these figures radically understate the cost. Every tank turned to wreckage in eastern Ukraine is factory time and material that cannot go towards consumer essentials, every bit of concrete that goes to repaving destroyed roads cannot go to making new ones, every wheatfield smashed by artillery is food that will go uneaten, and every soldier or civilian lost in the conflict means a family left broken. And of course, the pain so far inflicted on Ukrainian civilians is orders of magnitude larger than those inflicted on Russians. It’s impossible to quantify those costs, but they are tragically growing.

Thanks for this amazing article Joseph !

I am very impressed with the facts and analysis contained in this report. This what I don't see in the L.A. Times.