Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 29,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

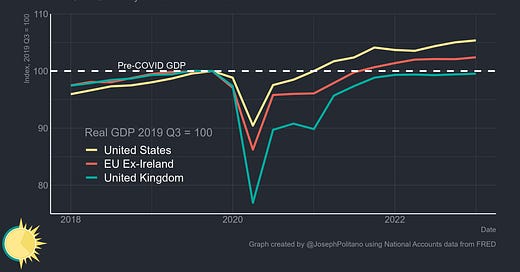

Since the start of the pandemic, the US economy has grown by 5.4%, the European Union’s economy, excluding volatile Irish data, has grown by 2.4%, and the UK’s economy has shrunk by 0.5%. Great Britain is one of only two major economies whose output has never recovered to pre-pandemic levels—ahead of only the world’s other prominent island of economic stagnation, Japan. The country’s economy has flatlined over the last year—notching essentially zero growth from the start of 2022 to today.

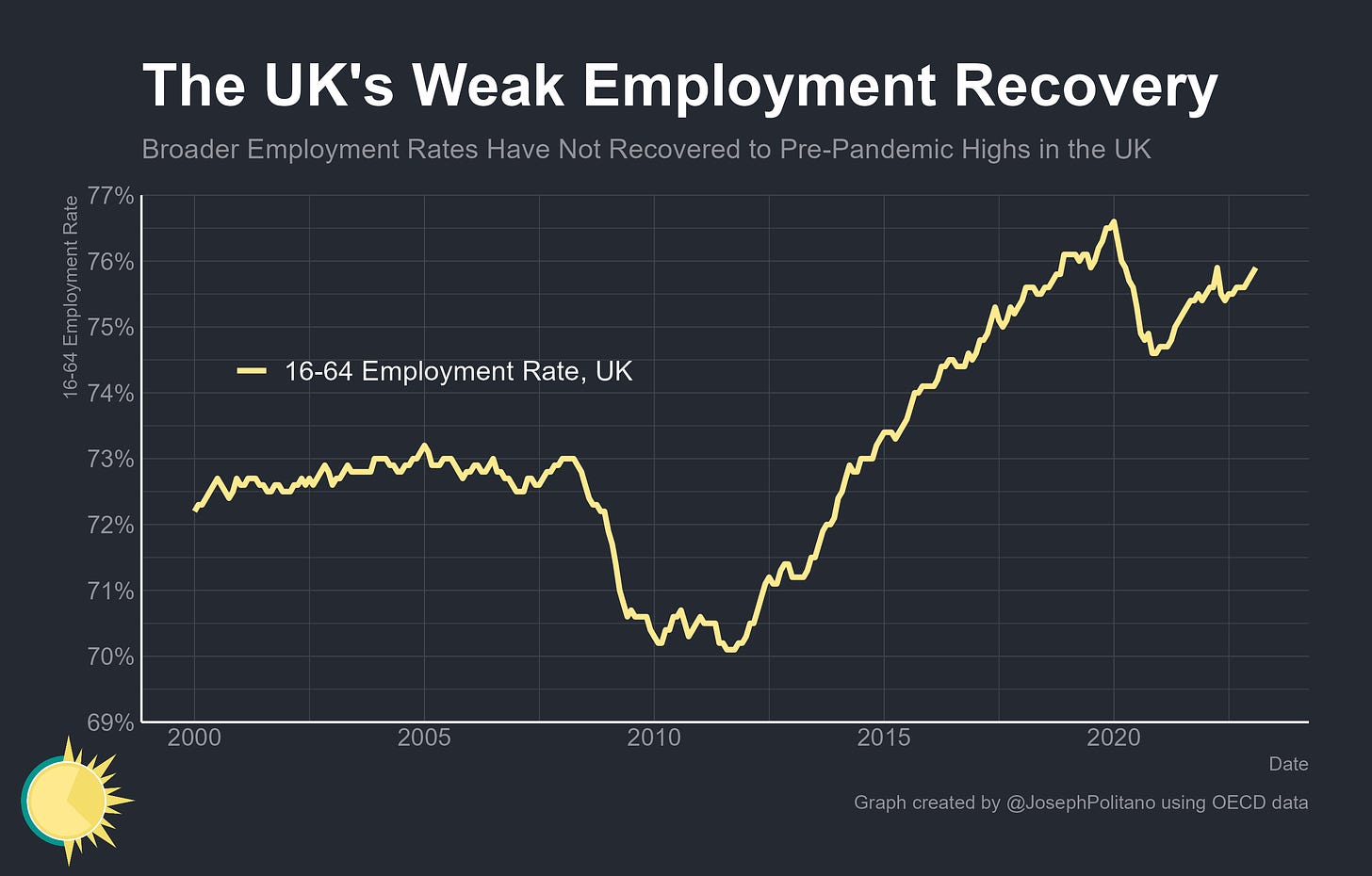

Not only that, but the UK arguably has the worst labor market recovery in the G7—they became the only major high-income economy where a smaller share of the working-age population was employed than in 2019 after American employment rates crossed pre-pandemic averages in Q1. Nations like Canada and Germany, which previously had smaller shares of their prime-age population at work than the UK, have since surpassed British employment rates.

Plus, the British inflation crisis remains among the worst in the world—amidst extremely weak real growth, headline CPI clocked in at 8.7% over the last year, only a smidge below the 9% it registered this time last year. Rapid increases in food and energy prices in the wake of the war in Ukraine have caused headline inflation to soar, but even core inflation is currently at a red-hot 6.8%.

Despite some improvements in the outlook, those in power still expect the dismal state of affairs to get worse before it gets better—the most recent projections from the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee show a modal GDP growth rate of under 1% for the next two years, with unemployment expected to rise to 4.3%. In other words, Threadneedle Street believes that the British economy will be a meager 1% bigger than pre-pandemic levels by 2025 and that there may well be fewer jobs than in 2019— making the first half of this decade a possible period of declining living standards in the UK.

Much of the weakness stems from idiosyncratic shocks—the UK officially exited the EU just as the pandemic was starting, missed out on the €750 billion in common EU debt as part of COVID recovery efforts, and was dependent on imported natural gas, the price of which shot up after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Yet the bigger picture is one of deep structural issues—for the better part of the last 10 years, the UK has suffered from anemic productivity growth and persistent underinvestment, and that’s bearing fruit in the form of today’s stagnating economy.

Britannia's Blues

Broadly, the UK had a much more defined initial shutdown than most countries did in 2020, and they recovered later than most economies— spending the bulk of 2020 and 2021 lagging behind their continental and overseas peers. There was a mini manufacturing boom as demand for goods propelled production industries to new heights in late 2020, but that began waning just as services production began ramping up in 2021. Yet services output never really moved from its late-2021 highs, with the decline in production being offset by growth in construction output to keep net economic growth near zero.

The slowdown in services output and fall in production are both somewhat due to the worldwide shock to food and energy prices in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—perhaps the most flattering analog to the UK’s economy is Germany’s, which also remains smaller than pre-pandemic levels thanks to two recent large successive GDP declines. The UK is a large importer of food and energy—two items that surged in price over the last year, leading to record trade deficits totaling more than £90B over the last 12m, and a massive supply shock that pushed back the British economic recovery.

The energy shortage, for example, bookended what was a very short UK industrial rebound—aggregate manufacturing output rallied quickly from the initial pandemic shock but began sliding in 2021 and 2022. Rising natural gas disproportionately stymied energy-intensive manufacturing like metal, paper, and most importantly chemicals, leading to a noticeable overall crunch in British industrial output.

More importantly for the UK’s consumer-based services-driven economy, however, has been the weakness in real spending amidst elevated broad-based inflation. Compared with early 2019, the country is spending 20% more on retail goods yet consuming essentially the same amount in real terms—in fact, real retail sales spending has steadily declined more than 10% from its 2021 highs even as households spend more and more cash on goods. Real consumption of services has also stagnated while prices rise at multi-decade-high rates.

The poor performance across all aspects of real domestic consumption, compounded by the relative weakness of the UK’s direct initial stimulative response to the recession, has resulted in an employment rate still below pre-pandemic levels. Much of this decline has manifested as a drop in male employment, which remains more than 1 full percent below pre-pandemic levels—representing 200,000 “missing” workers. Yet the short-run factors are only half the economic story—the UK’s economic fundamentals have been weak for years, leaving them susceptible to the kinds of shocks stronger economies could brush off.

Longer Term Issues

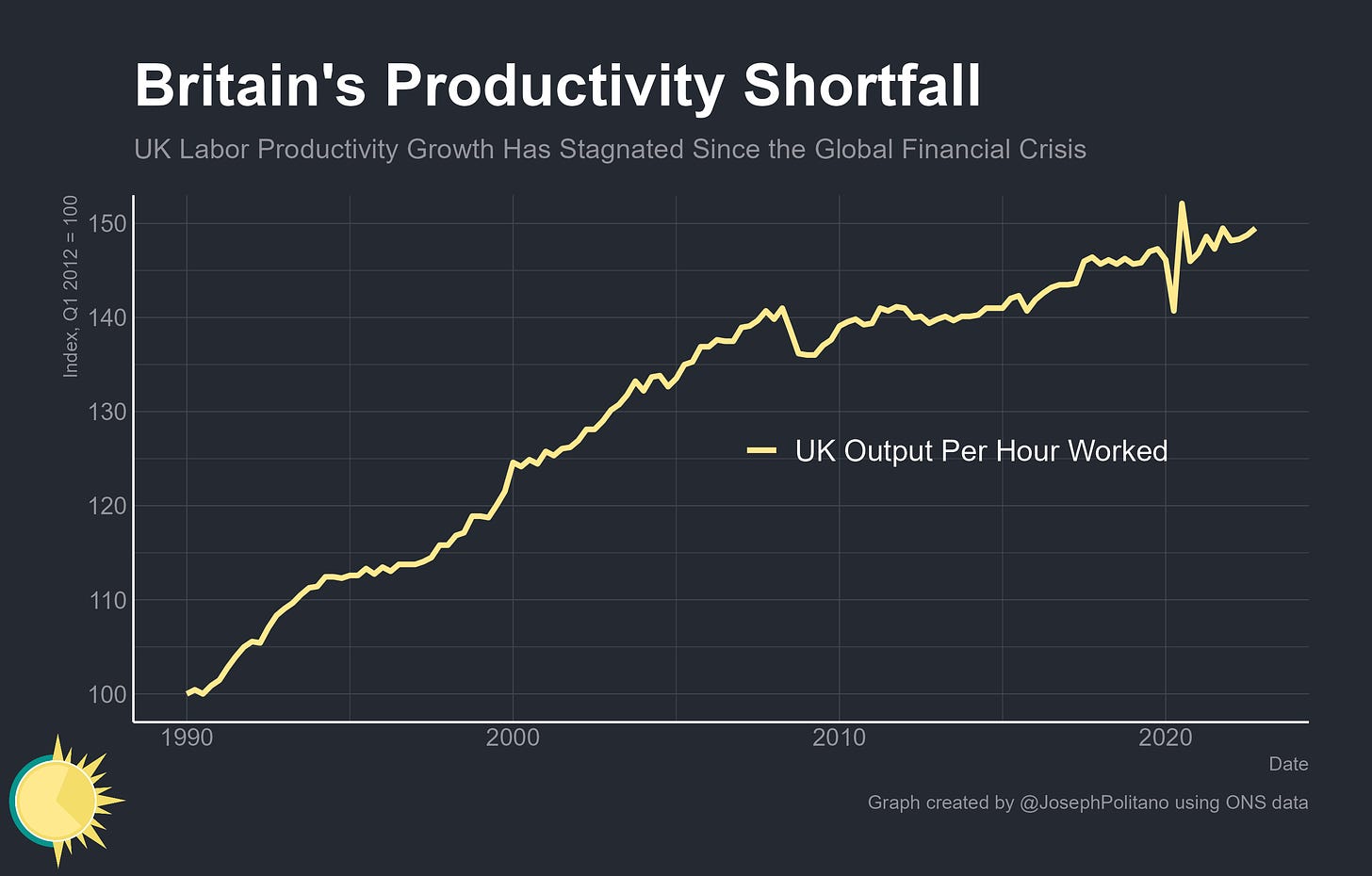

Arguably, the largest issue in the UK has been the persistent weakness in labor productivity growth since the Global Financial Crisis. Like most high-income nations, the UK saw sharp decreases in productivity growth—in fact, the UK got off easier than most of its European neighbors by virtue of having a separate monetary policy from the Euro, meaning their productivity growth declines were “only” in the ballpark of America’s. On the flip side, their labor market policies were able to protect many more jobs than those of the US—employment rates started out more than a half percent higher in the UK and recovered to pre-recession levels 5 years faster. Yet recent history has been particularly brutal—despite the smaller workforce, which tends to mechanically raise observed productivity for no other reason than because low-wage workers are usually among the first to lose jobs and cease dragging the average down, the UK’s productivity has barely increased. Though too much should not be made of short-term productivity moves, it’s still worth noting that US productivity is up 3.7% since 2019 despite a growing workforce that is bringing in marginal workers. Meanwhile, British labor productivity is only up 1.5% in an environment where many marginal workers remain out of a job.

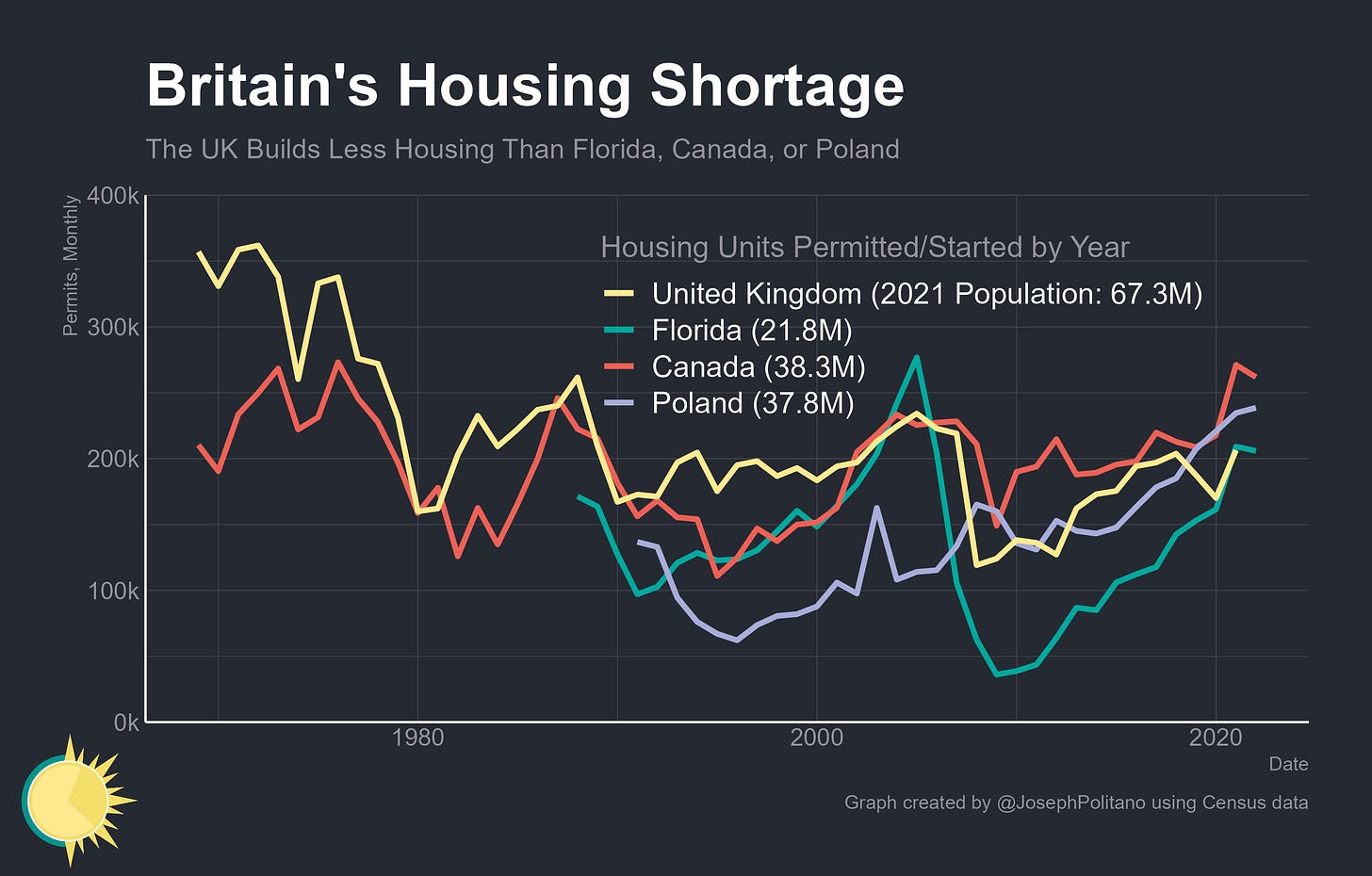

The UK’s acute and worsening housing shortage plays a large part in this productivity slump—despite having a smaller dwelling stock than France and a population roughly on par with the entire American midwest, Great Britain builds remarkably little housing. Florida, Canada, and Poland—all countries with significantly smaller populations than the UK—started more units last year than the entirety of the UK. The Texas Triangle of Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, and Austin alone permitted 218,000 housing units in 2022, compared to 178,000 in the entirety of England. That’s a large part of the reason why a median London renter could expect to spend 40% of their household income on rent in 2021—a number that has likely only increased in the years since.

That looks even worse considering the recovery, like much of the UK’s recent economic growth, has been uncomfortably concentrated in a select few regions—as of the most recent data for Q3 2022, London’s economy was 4.4% larger than pre-pandemic levels, the economy of North West England (the region containing Manchester) was 2.6% larger, and every other region of England and Wales had either just barely recovered or remained below 2019 output levels. Successive governments have tried to encourage growth to spread outside London via “leveling up” plans and other policy schemes to limited success—and unless the tight constrictions on housing growth within the London area are alleviated, a regionally concentrated recovery is definitionally not one the majority of Britons can fully participate in.

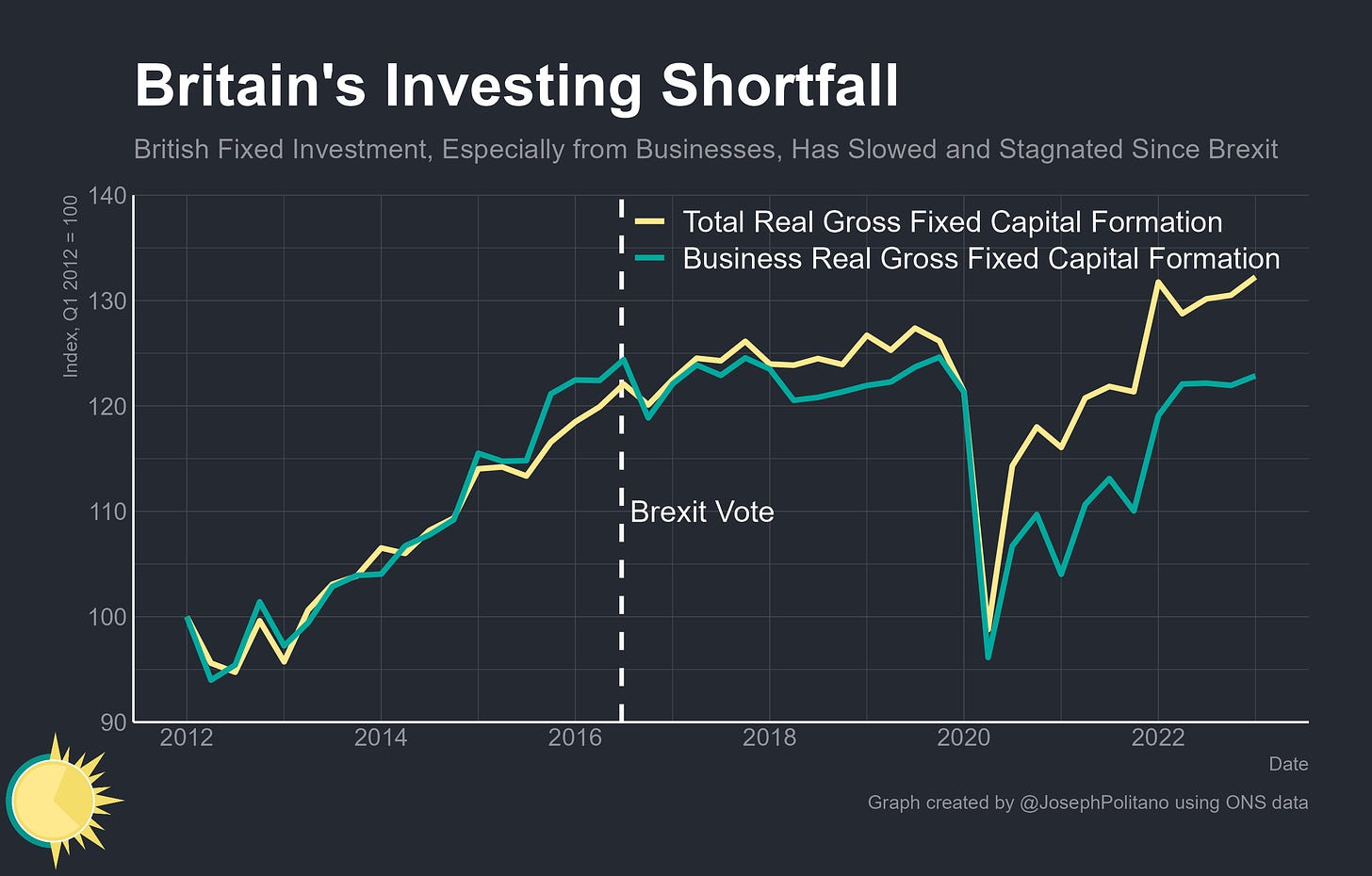

More broadly, the UK has still not seen real business investment recover to the highs seen just before the Brexit vote in late 2016 rattled the country’s standing in global markets. Government investment has helped make up some of the difference in the pandemic-era economy, but it’s still not been enough to propel real investment to sufficient levels. With interest rates rising, residential fixed investment suffering, and the economic climate remaining sour, business investment outlook remains weak—and those foregone investments will continue to impair British economic capacity for years to come.

No Way Out But Through

Though many reform efforts have fizzled out, like the mini-budget fiasco of late last year, there have been some genuine efforts at prodding the economy forward. After Brexit cut the UK off from free migration with most European nations, the country developed a fairly good points-based immigration system that has made it much simpler for qualified non-EU workers to move to Britain. The total number of working foreign nationals now sits at 5M, a record high, helping buoy the economy through its recent tribulations. To regain some presence in global markets, the UK is looking to sign the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) with 11 countries and is attempting to sign free-trade agreements with bigger partners like India and the US.

Plus, there has been some consistently good news from policymakers and professional forecasters regarding Britain’s short-term economic outlook. The IMF, which previously expected the UK’s economy to contract in 2023, has upgraded its growth forecast to a positive 0.4%. Meanwhile, the Bank of England’s forecasts, though still exceedingly dismal, are much better than the apocalyptic expectations from earlier this year—unemployment is projected to rise to “only” 4.3% instead of 5.1%, and GDP growth is no longer expected to be negative throughout much of 2023 and 2024.

Weathering the storm in the short term is good—but will just leave the UK muddling through in much the same way it has for the last few years. Without fundamental changes to address the underlying issues holding back the British economy, the UK could still be on the brink of a lost decade of economic growth.

One other factor is the appalling state of the UKs health service. Long waiting lists have prevented many people who could return to work from doing so.

It would also be worth mentioning the huge problems Britain's non-London cities have with transport, and how that destroys a lot of the potential benefits of agglomeration, see https://www.tomforth.co.uk/birminghamisasmallcity/