Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 10,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

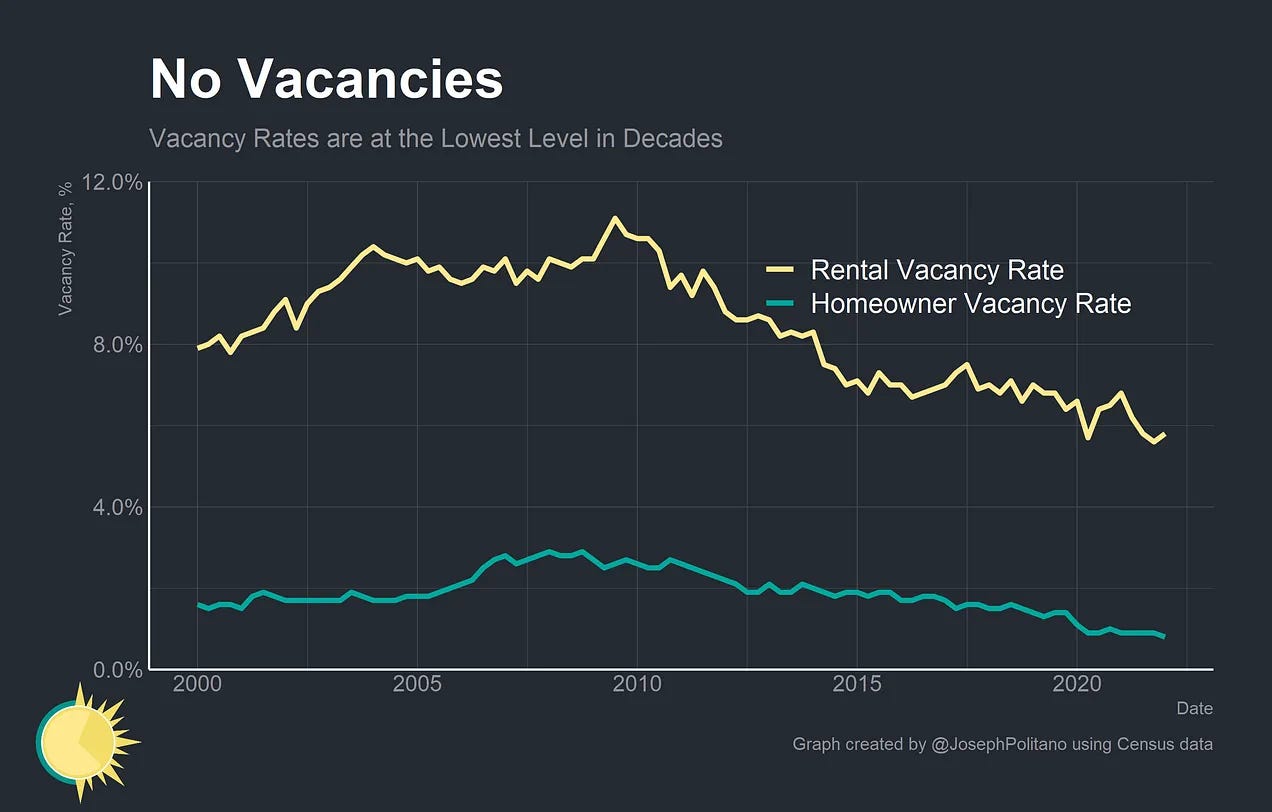

America has an acute shortage of housing. Its largest and most prosperous cities impede, restrict, or forbid large amounts of construction, and since the Great Recession output of suburban single-family homes has remained depressed. Real rents increased at the fastest pace in history during the late 2010s, housing vacancy rates remain near historic lows, and record numbers of young Americans live with their parents due to housing unaffordability.

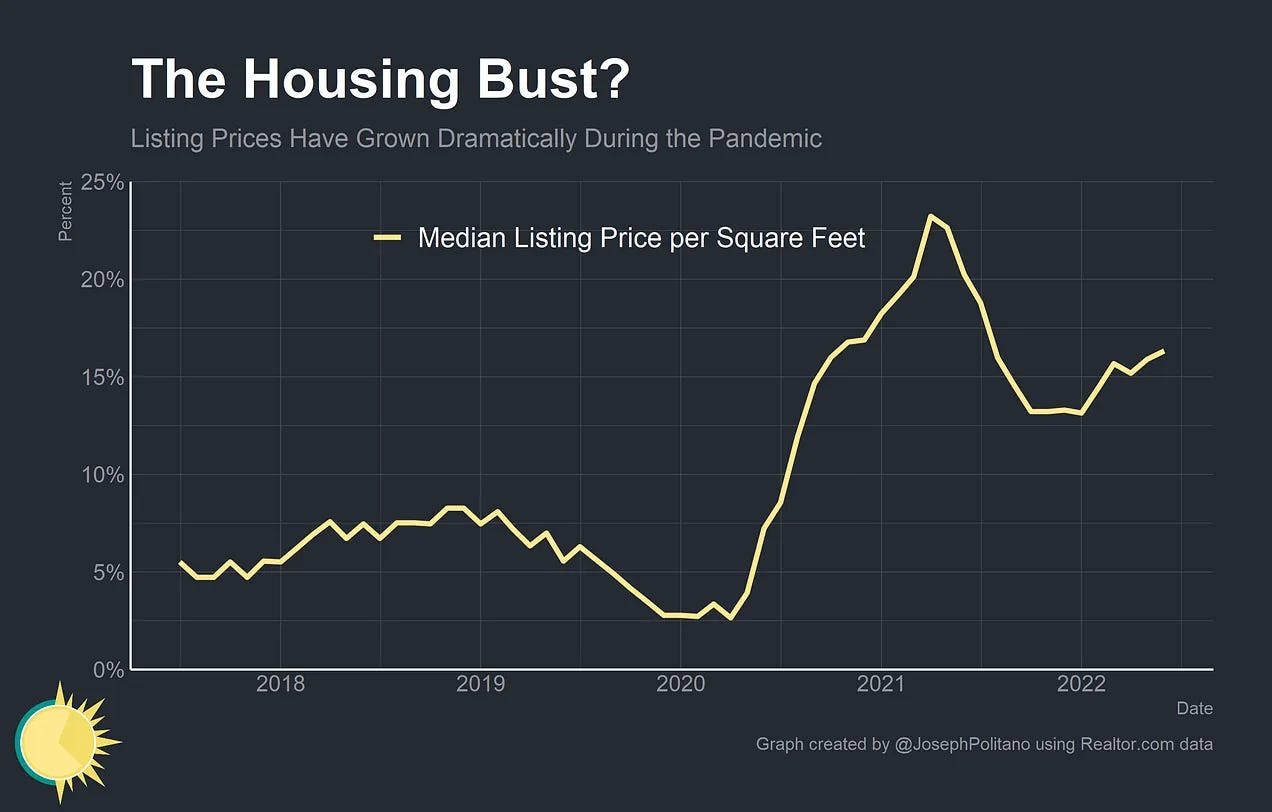

For the better part of the that last decade, home prices in America have been on a slow march upwards as higher wages and employment levels mixed with structural underconstruction. The pandemic sent the housing market into overdrive—work from home supercharged demand for residential living spaces, changing migration patterns upended local housing markets, lower mortgage rates pushed up prices, and supply-chain issues impeded construction projects.

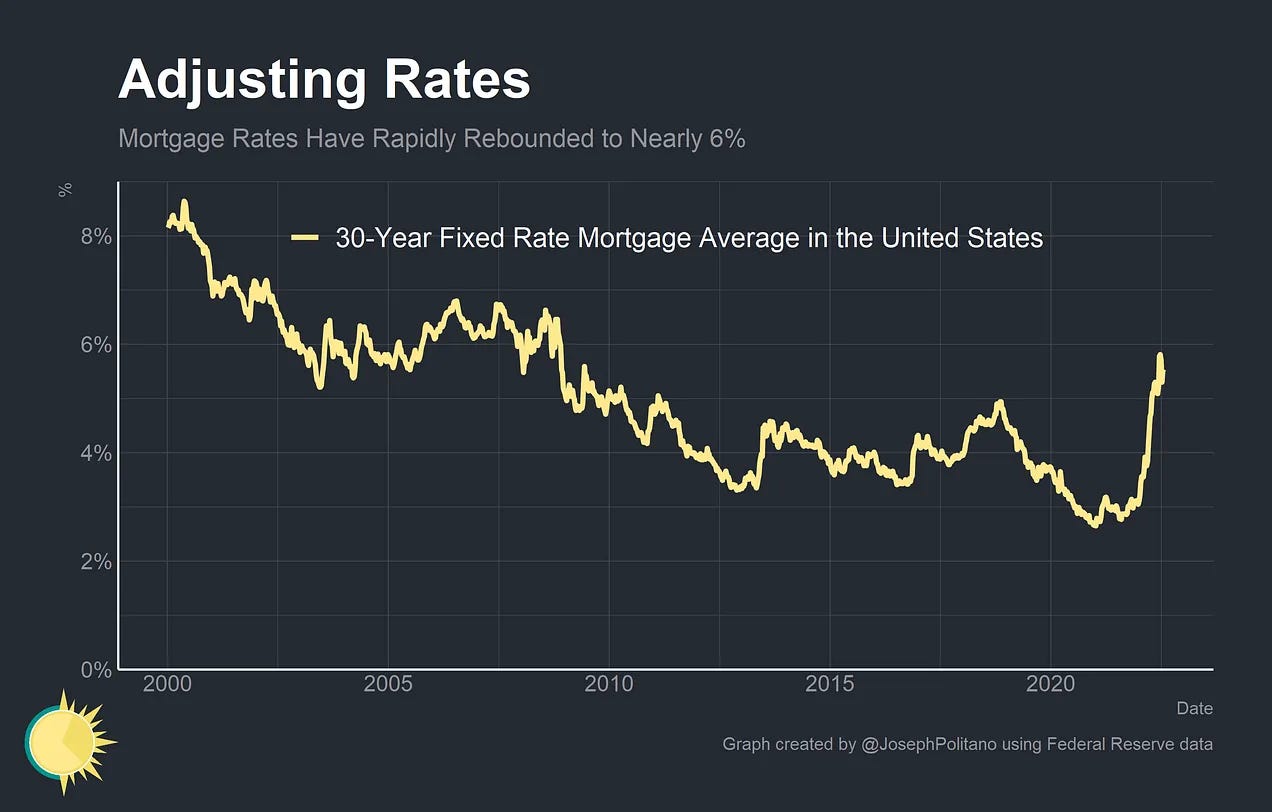

Now, the focus of the Federal Reserve is on constraining credit in order to combat inflation. That's manifested in higher interest rates across the curve, including higher mortgage rates. In fact, mortgage rates are now higher than at any point since 2010, though they have pulled back a bit from their recent jump to almost 6%. Those higher mortgage rates are turning the housing market upside down—dropping mortgage applications, pulling down homebuilder sentiment, weighing on prices, and crushing housing starts. This mixture of higher rates, strong employment and wage growth, and supply deficiencies is unprecedented in the American housing market.

Mortgage Market Mayhem

Critically, the movements in mortgage rates are unique in modern American history for both their size and speed. After hitting an all time low of 2.6% in early 2021, the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate surged to 5.8% by January 2022 before sliding back to their current levels. Still, the last time mortgage rates were this high was late 2008.

Higher long-term treasury rates explain a lot of the move, but they are by no means the full story; mortgage rates have risen faster than comparable treasury rates. The rising spread has a lot to do with an explosion in interest rate volatility and and inversion of the treasury yield curve, both of which tend to push up mortgage rates in excess of treasuries (keep in mind that mortgages can be refinanced, treasuries cannot).

The rather immediate effect of rising mortgage rates was to curb some of the price growth across the housing market. Growth in median listing prices is tapering off, and the share of listed units with a price cut jumped up to 40% in June. Housing is a long-duration asset, meaning it is sensitive to interest rate movements, and the scale of mortgage rate increases means that monthly payments on an equivalent-price home have spiked more than 50%. That's definitely taking some of the wind out of price growth, though the counteracting forces of heightened demand and reduced supply are definitely providing an opposing push.

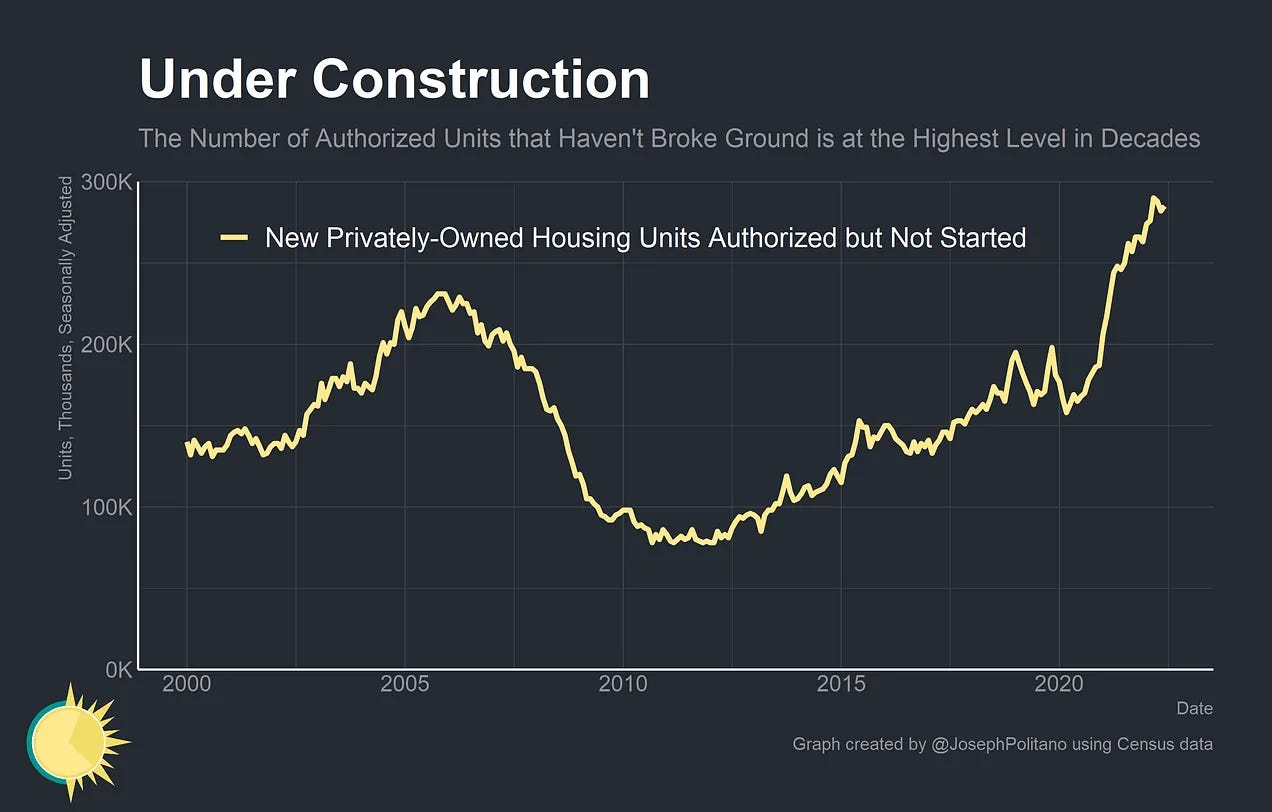

In the short-term, though, the rise in mortgage rates has primarily manifested as a shock to construction. Since the start of the pandemic, supply-chain issues have kept single-family starts ahead of completions as construction times increased and materials remained in short supply. Now, completions are finally outpacing starts—but only because single-family housing starts are down 20% from their pandemic highs thanks to higher mortgage rates.

Multi-family housing starts remain robust, which may partially reflect a re-shifting in locational preferences and migration patterns in the US. The post-2008 period was dominated by stronger housing markets in the cores of major urban areas like New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, DC, Boston, and others. Financing restrictions and tighter mortgage credit post-2008 also contributed to reallocating construction from single-family units to multi-family. It will be critical to watch whether multi-family housing starts can hold up despite the decline in single-family starts or if apartment construction is merely a lagging indicator thanks to the longer construction times of multi-family real estate.

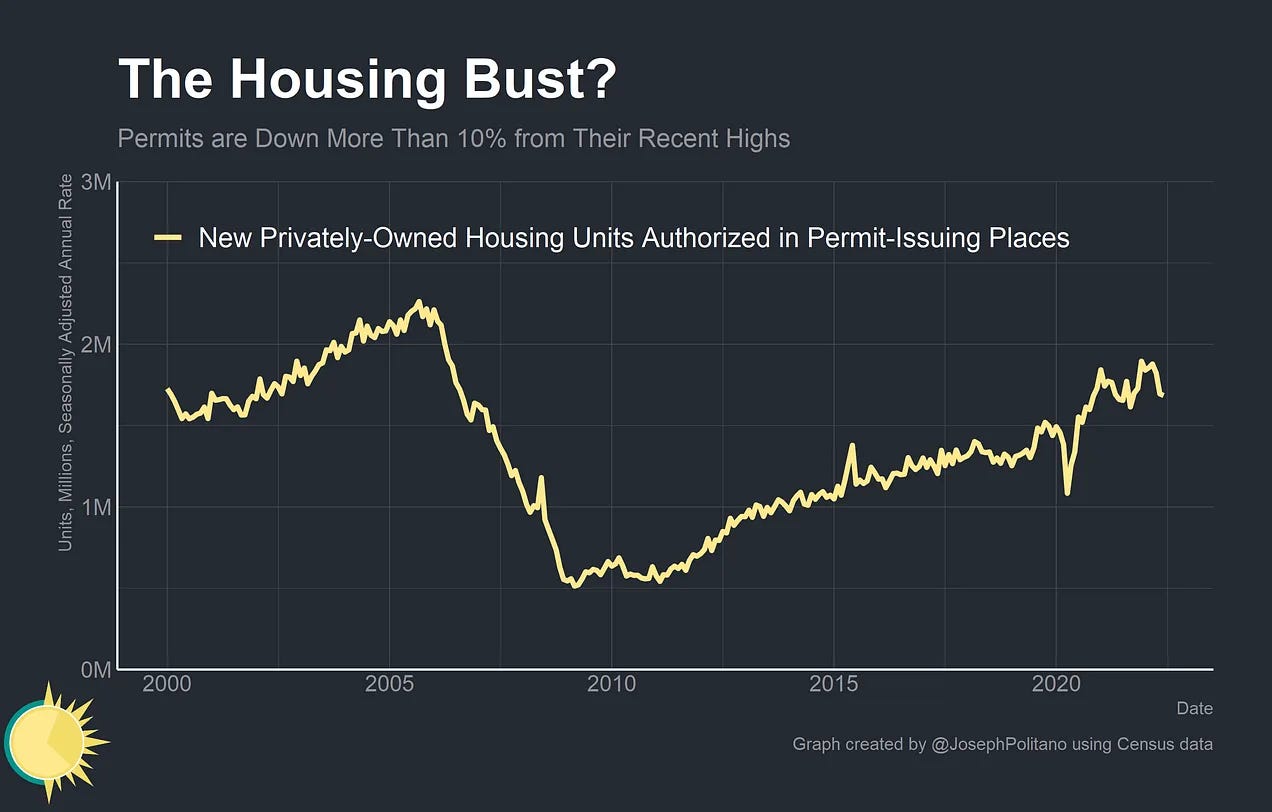

Permit issuance is also down 10% from its pandemic highs as the effects of higher interest rates weigh on homebuilder sentiment and demand. The National Association of Home Builders' homebuilder sentiment index plummeted to the lowest level since 2015 last month, and the pace of sentiment deterioration is only matched by the start of the pandemic and Great Recession.

In whole, the number of projects in various stages of construction remains high, so it is possible for significant new housing supply to come online in the next year even if initiation of new projects remains depressed. That could further weigh negatively on prices, but would also contribute to constraining rent growth and thereby inflation. The number of units that are already permitted but not started is just off a modern record high, and the number of units under construction remains at an all-time high.

But rapidly rising mortgage rates will also have downstream impacts on the people and businesses who rely on housing construction for work. In June employment for residential building and nondepository credit intermediation (read: mortgage lending) shrunk by 0.5% and 0.4%, respectively.

Conclusions

America is still going to have to deal with an acute shortage of housing even if rising rates cause average home prices to shrink. Fundamentally, there is not enough construction to keep up with population growth, income growth, and household formation. Estimates for the shortfall of housing units range in the millions, and housing vacancy rates (a decent non-price proxy for demand) remain at historic lows.

Even as real-time home prices appear to cool a bit, private sector measures of rent growth are decreasing but remain elevated. That's going to feed through to inflation in the near future, and further improvements on the supply front are needed to mediate price growth. Rising mortgage rates may have turned the housing market upside-down, but the housing shortage remains.

Good post. Hard to tell whether short term rate moves will overcome longer term shortages.

Minor typo: “though the counteracting forced of heightened demand” Forced should be forces.

Great post, sir. Very informative and the “to the point” explanations are much appreciated.