The US-China Chip War is Escalating

China is Buying Record Amounts of Semiconductor Manufacturing Equipment to Fortify its Chip Industry—While DC Tries to Clamp Down Harder With Sanctions

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 39,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Semiconductor chips are a ubiquitous facet of modern life—the trillion-plus of them produced each year are essential to the basic functioning of everything from consumer electronics to medical devices to motor vehicles. The global economy is just now exiting a period of acute semiconductor shortage—one that crippled manufacturing output across industries and contributed to the worldwide pandemic-era inflation spike—underscoring just how critical they have become to international supply chains. To those who worry about the possible opportunities or long-term risks of Artificial Intelligence, controlling chips is also the key to ensuring digital minds remain in responsible hands. Plus, chips are China’s single-largest import item and one where Beijing remains dependent on its Taiwanese rivals, making the international semiconductor trade a massive crux of global geopolitical tensions. That’s why the US has engaged in its single-largest industrial policy effort in postwar history designed to build out domestic semiconductor manufacturing capacity—culminating last year with hundreds of billions of dollars in private spending on semiconductor fabricator construction in the wake of significant incentives passed under the CHIPS Act.

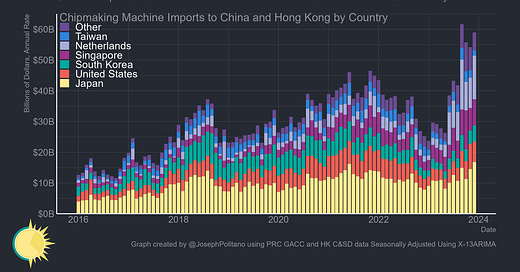

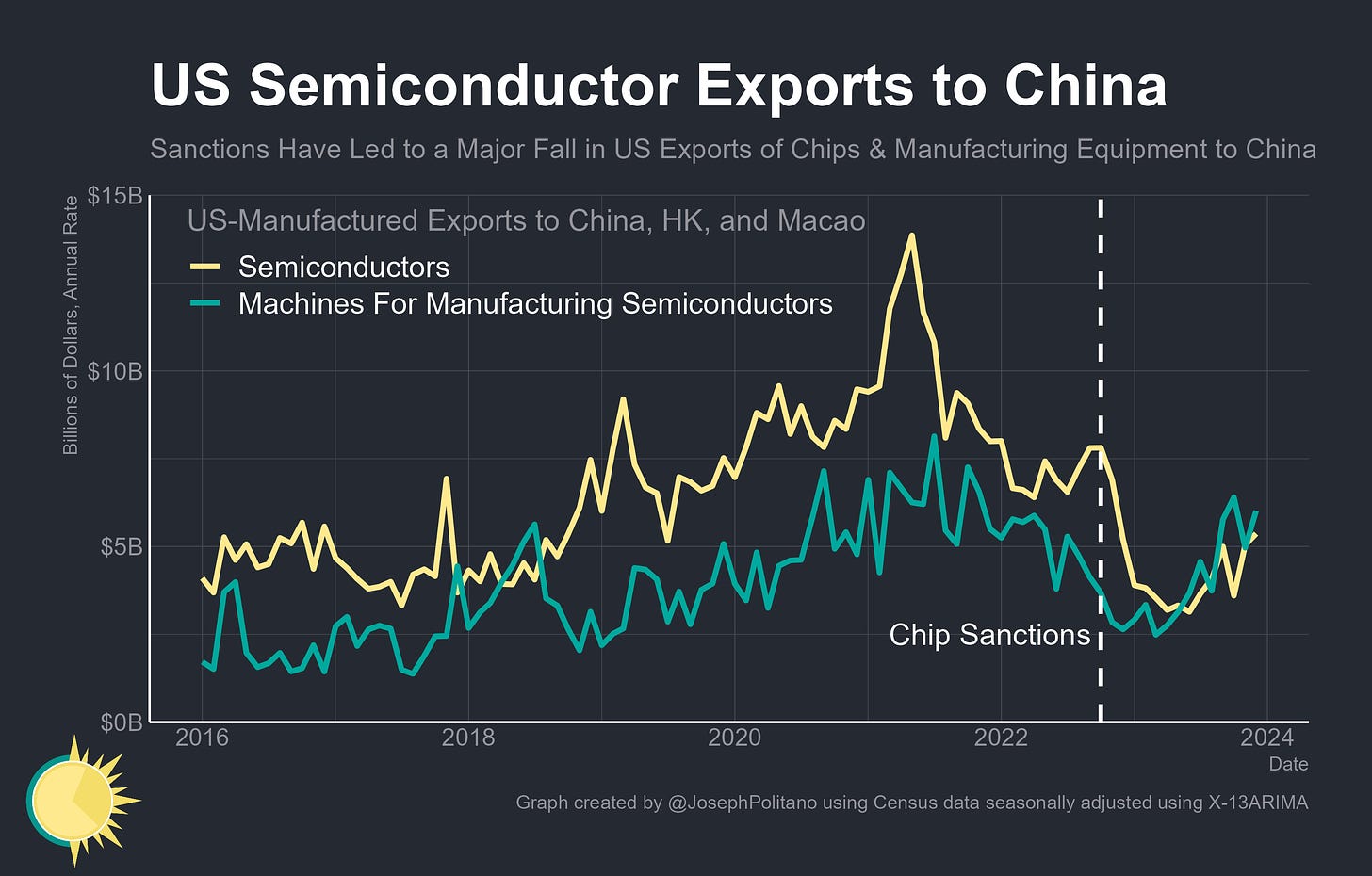

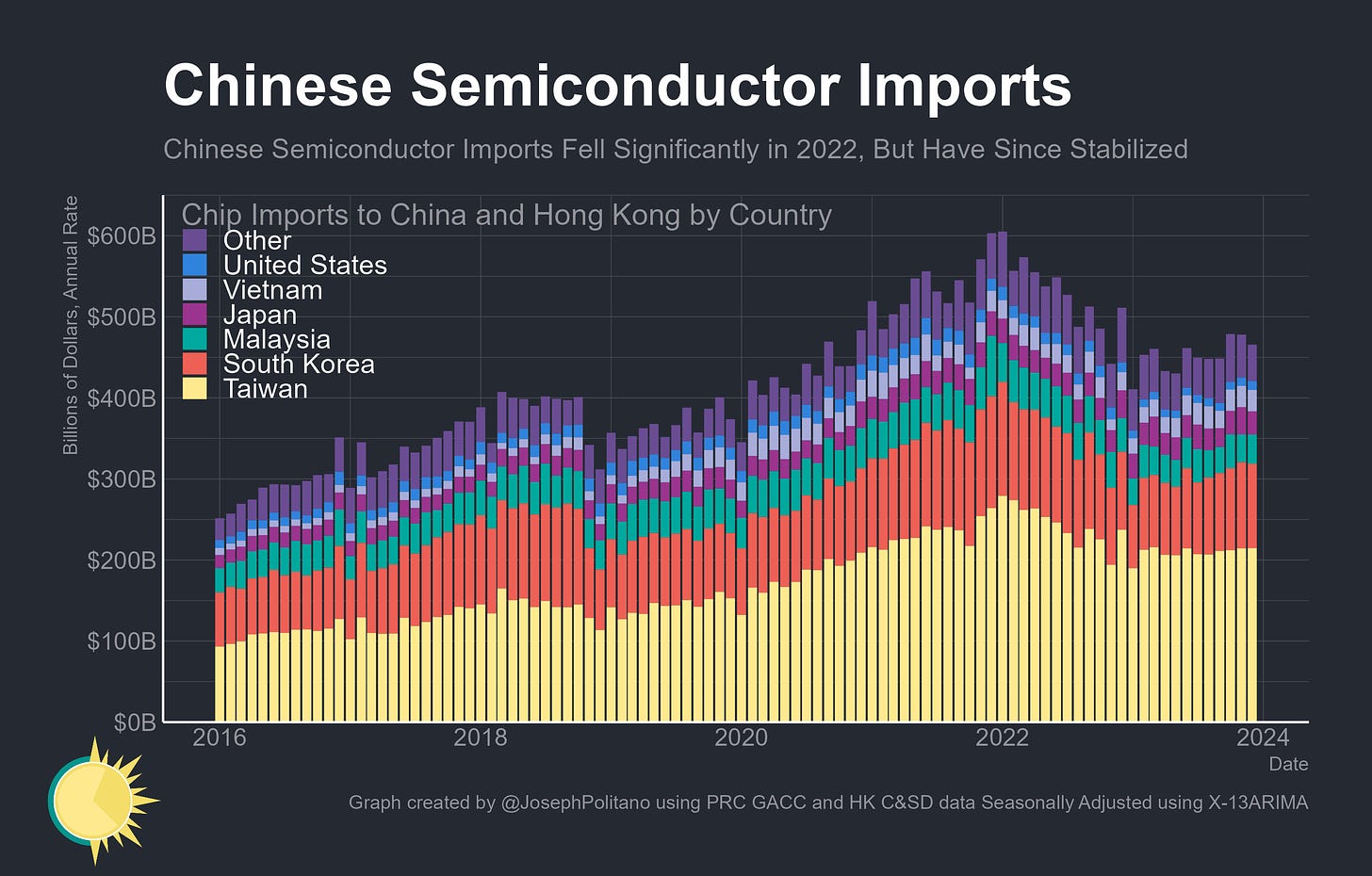

Yet there was an important second prong to the American chip strategy—in addition to the subsidies designed to restore US manufacturing capacity, Washington aimed to hamstring China’s domestic semiconductor and tech industries through sanctions that would cut Beijing off from key supplies. Those included restrictions on the kind of cutting-edge processing units currently highly coveted by AI and advanced tech firms, but it also included restrictions on the equipment that would enable China to accelerate its own domestic semiconductor production. At the onset of America’s comprehensive package of chip sanctions back in October 2022, there was an immediate dramatic fall in the amount of US-made semiconductors exported to China. There was also a similar drop in the exports of US-made semiconductor manufacturing equipment, but this did not last—Chinese imports of American chipmaking equipment have since fully recovered back to pre-sanctions levels.

In fact, China is in the midst of a massive semiconductor equipment buying spree that has sent the nation’s imports of chipmaking machinery to record highs. That includes a rebound in imports from the United States alongside a massive surge in imports from key chipmaking equipment centers like Japan, the Netherlands, and Singapore. In response to the semiconductor trade war, Chinese manufacturers are working to indigenize chip production and fortify their domestic electronics industry—racing to get ahead as Washington tries to tighten its grip with further sanctions.

China’s Chipmaking Equipment Buying Spree

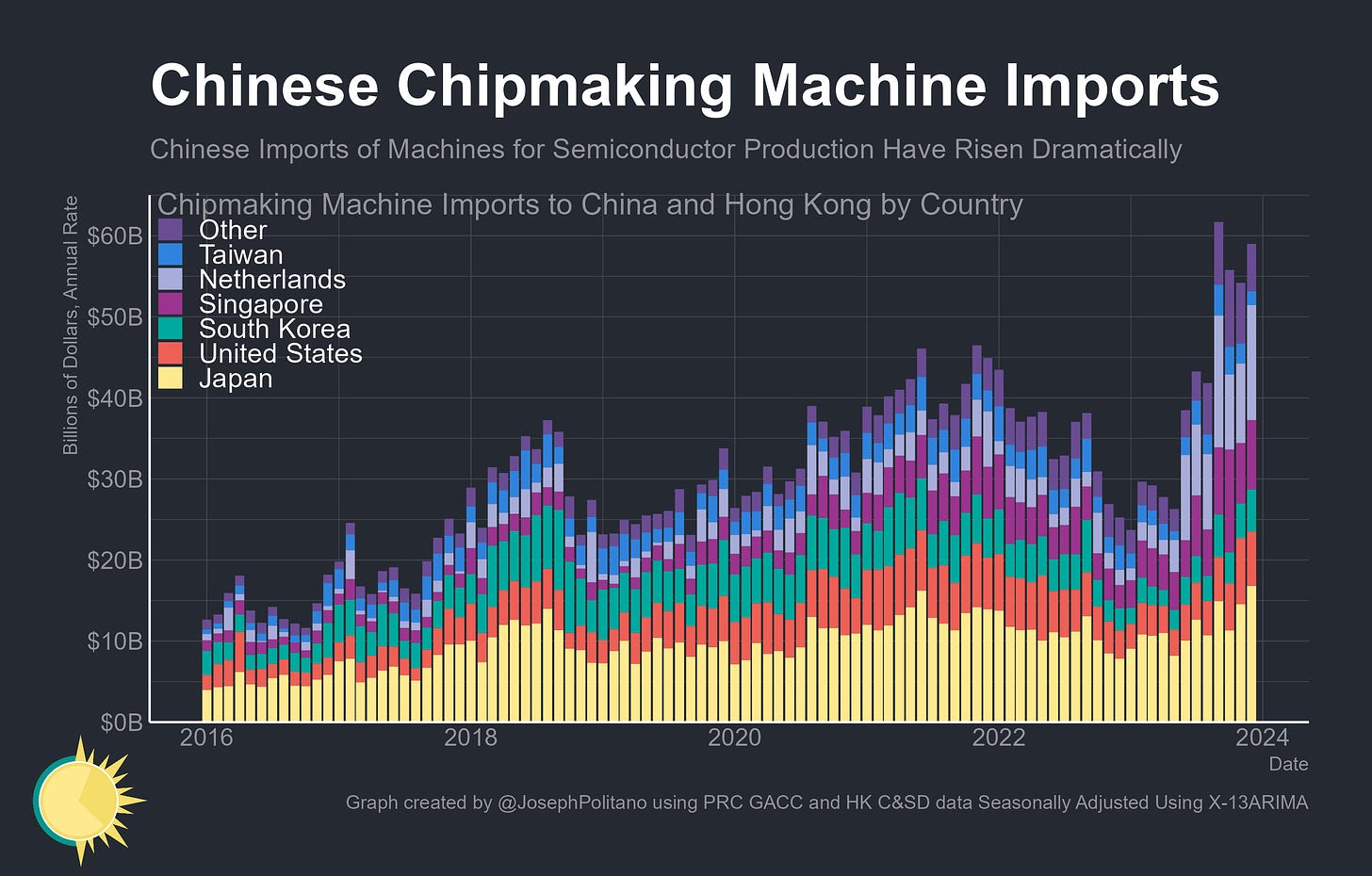

Last year, China imported record amounts of manufacturing equipment in categories throughout the semiconductor production process, but by far the largest increase came from “other apparatus used to project circuits”—a category primarily composed of the lithography equipment used to print circuitry patterns onto silicon wafers. Chinese imports of those lithography machines hit a record high of more than $7B in 2023, rising more than 270% from a year earlier. Imports of dry plasma etching machines used to carve out those printed circuitry patterns are also at record highs, as are imports of equipment used in Chemical and Physical Vapor Deposition processes that layer essential structures on carved-out patterns plus imports of the ion implanters used to then imbue those patterns with electrical properties. Chinese firms are also buying large amounts of the step and repeat aligners used as part of the lithography process, the heat treatment equipment used to control the properties of semiconductor materials, and even a variety of machinery used early in the production process to manufacture the silicon boules and wafers themselves.

The US makes up a significant portion of global manufacturing capacity for that semiconductor machinery, but it by no means has a stranglehold on the market—and in many areas, American firms still lag. That means DC is highly dependent on cooperation from its allies with key chipmaking equipment manufacturing centers for its sanctions policies to be successful—and the most important of those allies are the Netherlands and Japan.

The Netherlands is the headquarters and manufacturing home of ASML, the world’s leading semiconductor equipment giant and primary maker of key lithography equipment. In 2023, 29% of ASML’s total system sales were to China, up from only 14% in 2022, while the company’s net system sales rose more than 42%. That has shown up as a massive increase in chipmaking equipment exports from the Netherlands to China, which exceeded $5.8B in 2023. While none of those shipments represent the absolute-cutting-edge Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography (EUV) machines that ASML is famous for—the company has been effectively banned from shipping those to China for years—they do represent significant quantities of less-advanced lithography machinery that remain useful for a wide range of chip production. In 2023, the 176 machines bought from the Netherlands made up 85% of the dollar value of the PRC’s imports of “other apparatus used to project circuits.”

Meanwhile, Japan has also seen a significant rise in its chipmaking equipment exports to China, which have nearly doubled since the start of this year and for the first time outpace the country’s exports of semiconductors themselves. China made up 47% of key Japanese chipmaking equipment manufacturer Tokyo Electron’s net sales last quarter, up from roughly 20% in 2022, amidst a surge in demand for the company’s lower-end semiconductor machinery. Imports from Singapore are also up significantly, with American companies like Applied Materials, Lam Research, and KLA having major production facilities in the region—those three companies got 45%, 40%, and 41% of their revenue from China last quarter, up from 17%, 24%, and 23% this time last year, respectively. Chinese imports from an assortment of other nations with smaller semiconductor machinery industries have also risen, with that increase mostly being driven by Malaysia and non-Dutch members of the European Union.

America is keen to see those equipment import levels decline—which is why last year, the US came to agreements with both the Dutch and Japanese governments to restrict the exports of key semiconductor equipment to China. The Japanese export controls came into effect in late July, and the Dutch restrictions took effect in September—although they permitted the export of previously approved material to China so long as deliveries occurred before the start of January 2024. In other words, a large driver of China’s recent buying activity has been a push to acquire equipment before exports are restricted by intensifying sanctions, and imports could drop as trade curbs actually come into force. ASML, for example, expects exports of certain midrange equipment to China to drop 10-15% this year as restrictions bite down harder.

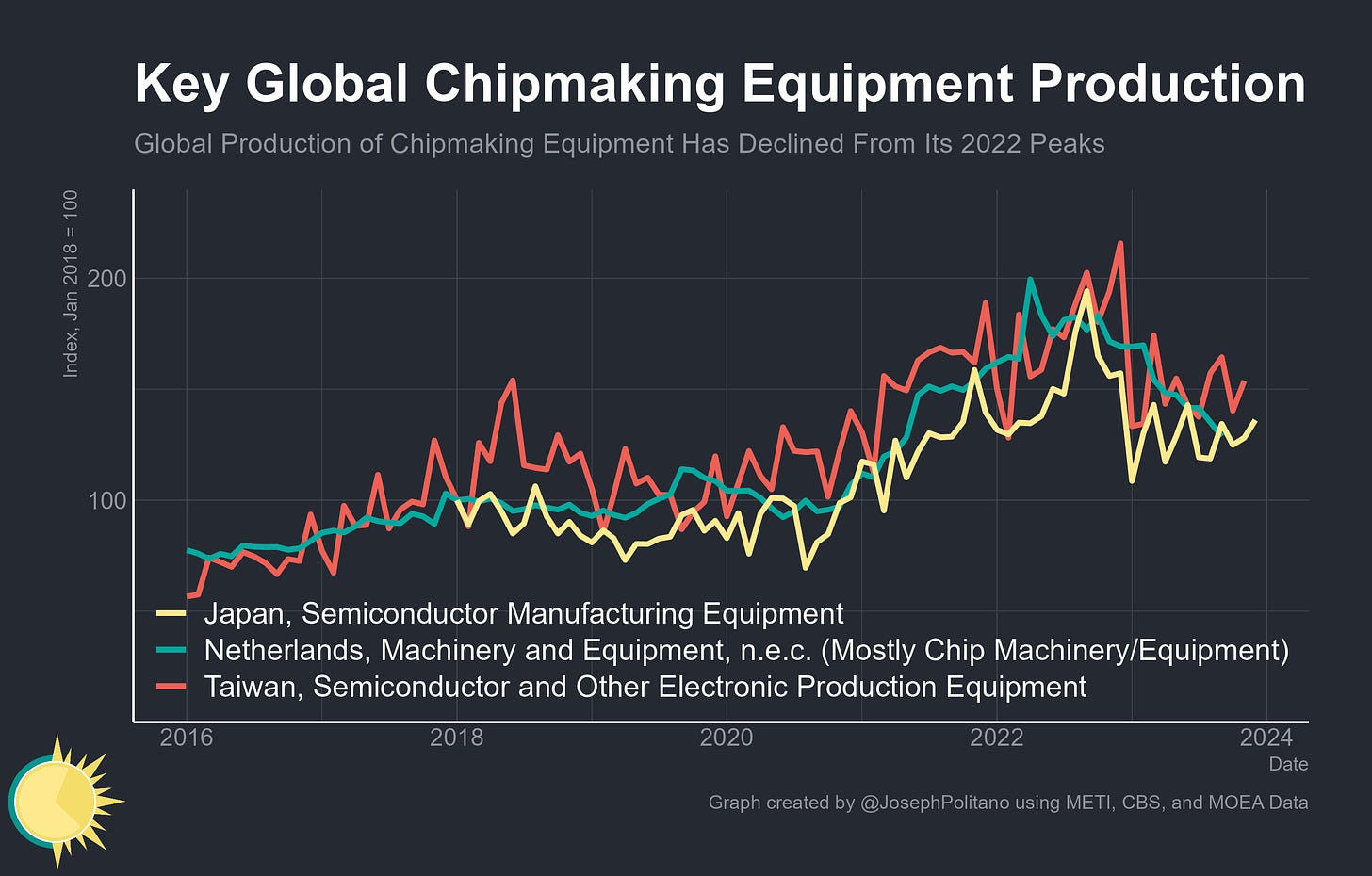

Yet despite these record Chinese import numbers, production of chipmaking equipment across key manufacturing centers has dropped significantly in 2023—cooling off after basically doubling amidst the record electronics demand and chip shortages seen through the first three years of the pandemic. The long lead times between order and shipment for semiconductor machinery means that most of today’s imports represent orders from last year and production that occurred months ago, ergo cooling chip demand and the specter of upcoming sanctions forced companies to cut back on production as they steadily cleared through their backlog of orders.

That prior slowdown in the semiconductor industry and sanctions on China could present an opening for American chip fabricators to scoop up new machinery, but so far they have not yet been able to take full advantage of that opportunity. US imports of semiconductor equipment, while robust compared to pre-pandemic levels, are currently nowhere near the level or growth rate of Chinese imports. That’s in part thanks to significant delays among a wide range of CHIPS Act construction projects that now plan to open behind schedule.

Taking a Broader View of the Chip Wars

Of course, US sanctions have not just been designed to limit Chinese access to the machinery necessary to manufacture semiconductors—they have also been aimed at safeguarding access to the highest-end chips used in AI training and other advanced computing. Yet despite its significant lead in advanced semiconductor design, the US has even less leverage as a direct manufacturer in the chips market than it does in chipmaking equipment, as American-made semiconductor exports represent only a small fraction of Chinese imports. For its sanctions policies to be successful, DC required significant cooperation from its chipmaking allies, principally Taiwan and South Korea, where China currently gets the bulk of its chips. The last two years have seen a decline in Chinese semiconductor imports from their 2022 peaks in part due to trade restrictions, although much of it is just downstream of the cyclical slowdown in the chips and electronics industry after the pandemic-era boom.

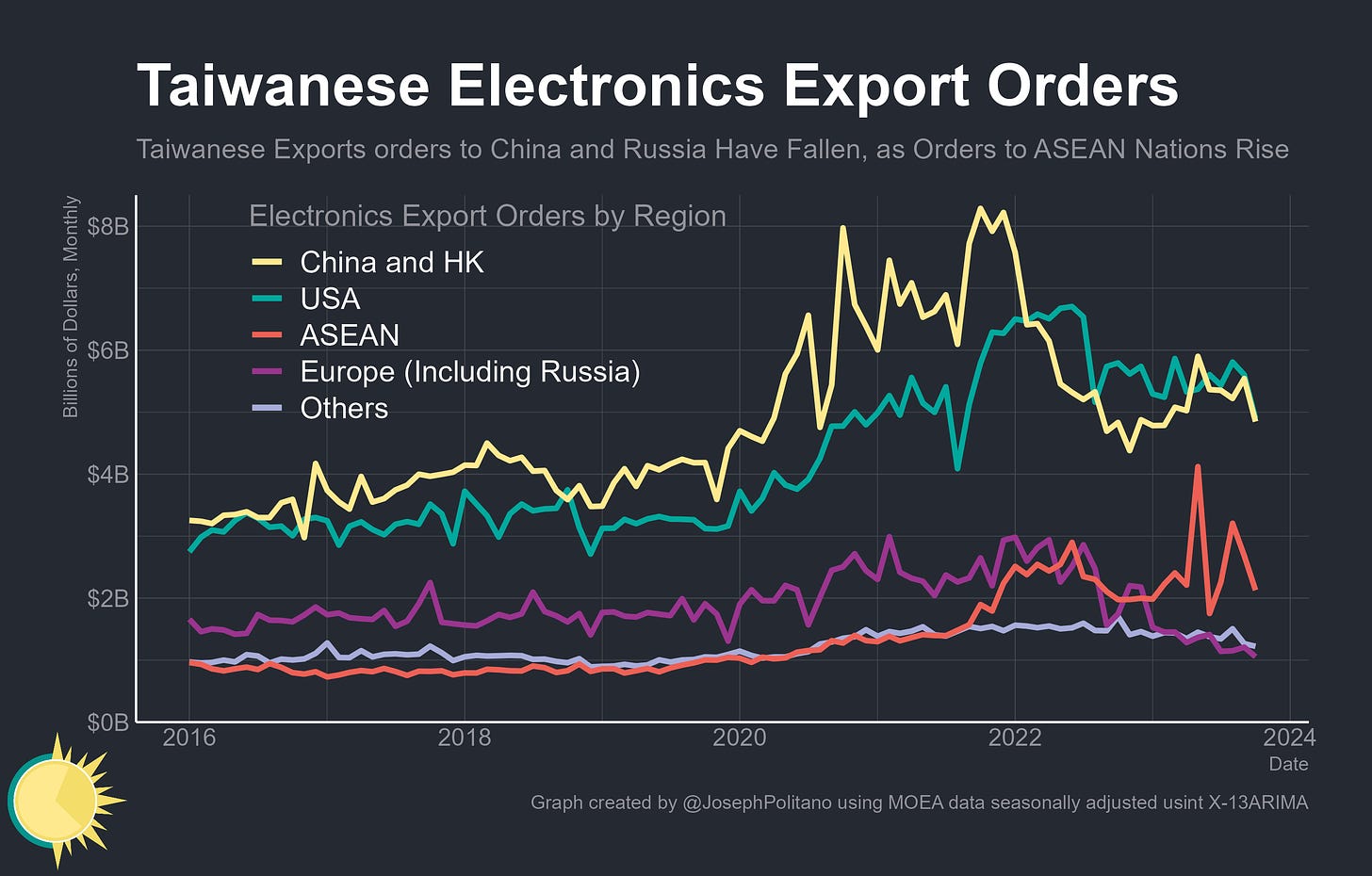

Yet Taiwanese manufacturers have seen a large drop in their orders destined for Hong Kong and China, plus a large fall in European-destined orders (mostly representing the declining trade with Russia). At the same time, exports to the United States and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) are booming, with America overtaking China as the number one destination for Taiwanese-made electronics for the first time in years. Sanctions, in other words, have significantly reshaped the Taiwanese semiconductor trade, directing chips away from China and Russia and nudging them toward consumers in the USA and electronics factories in ASEAN members.

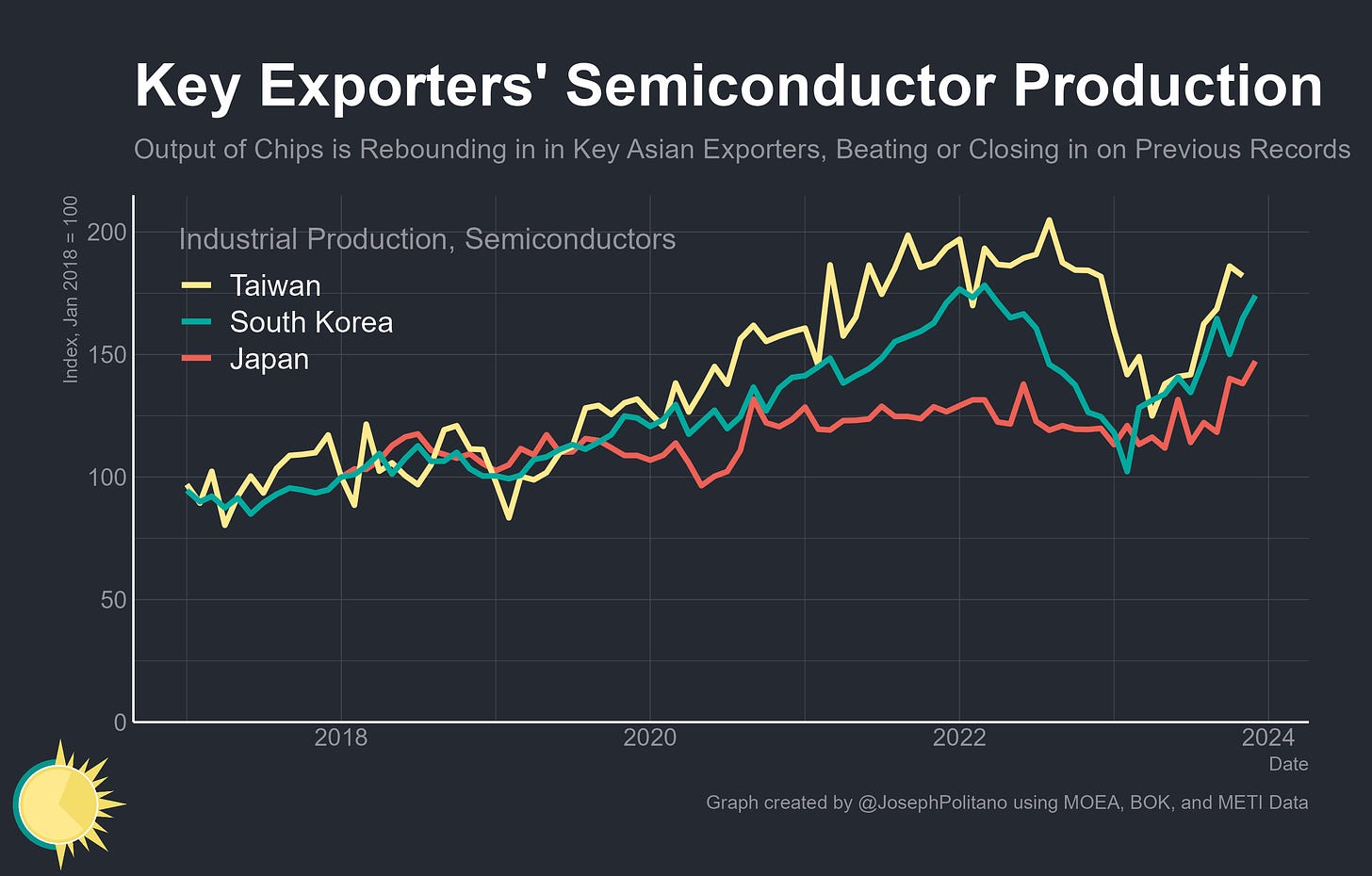

That has occurred as overall semiconductor production has rebounded among major Asian exporters after taking a steep dive in 2022—right now, Japanese production is at record highs, while Taiwanese and Korean production are closing in on their prior peaks. Given the relatively steady levels of Chinese imports from these countries, that means as headline production is rebounding a smaller share of output is headed to China.

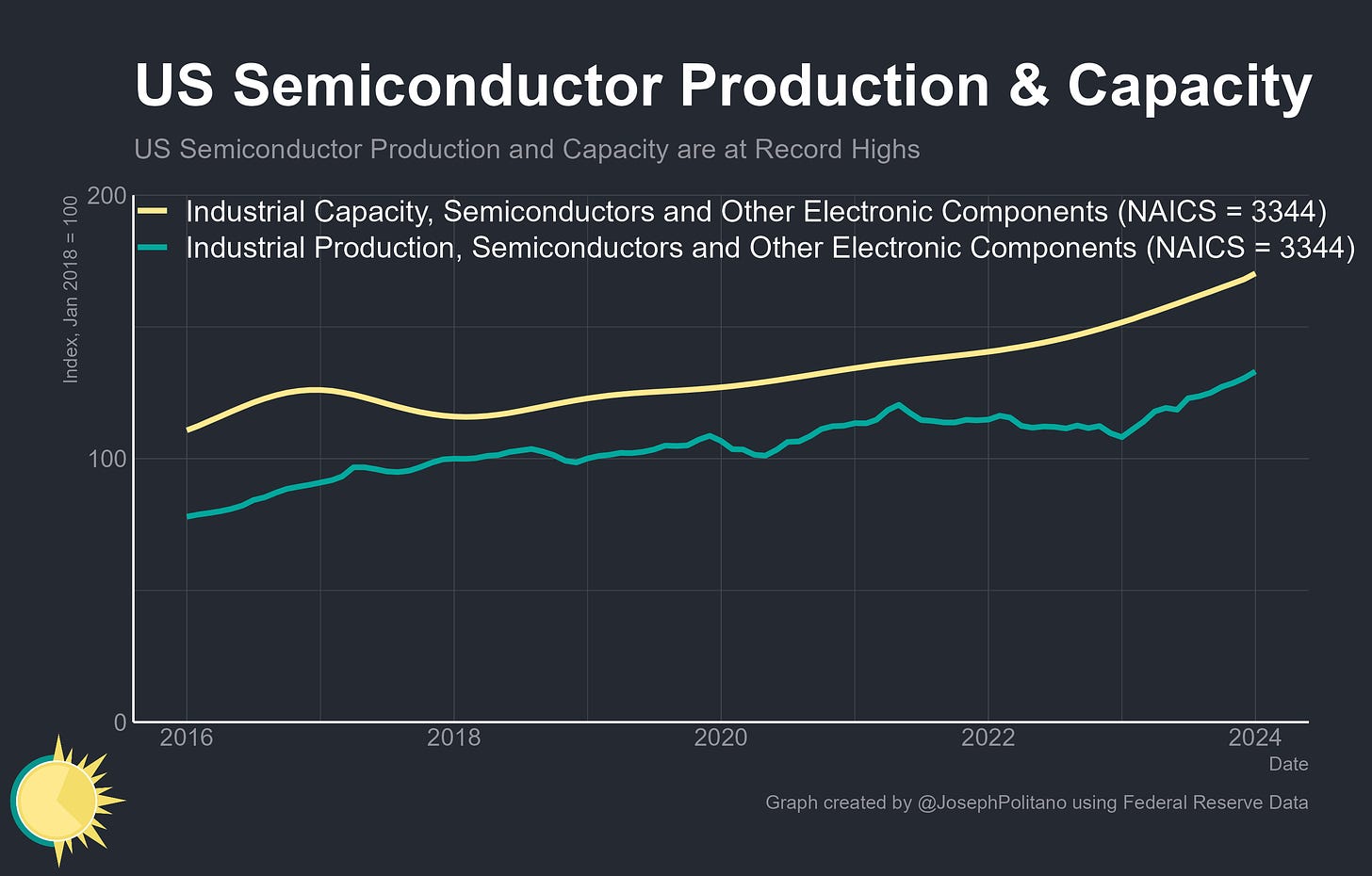

American production of semiconductors and other electronic components is also hitting new record highs, rising 23% over the last year alone while capacity has grown roughly 12%. The dollar value of US computer and electronics manufacturers’ shipments is now at the highest level since the Great Recession, although it remains well below the record highs set just after the turn of the millennium. Again, that growth is even though most CHIPS-Act-supported semiconductor fabricators still have yet to come online or enter mass production.

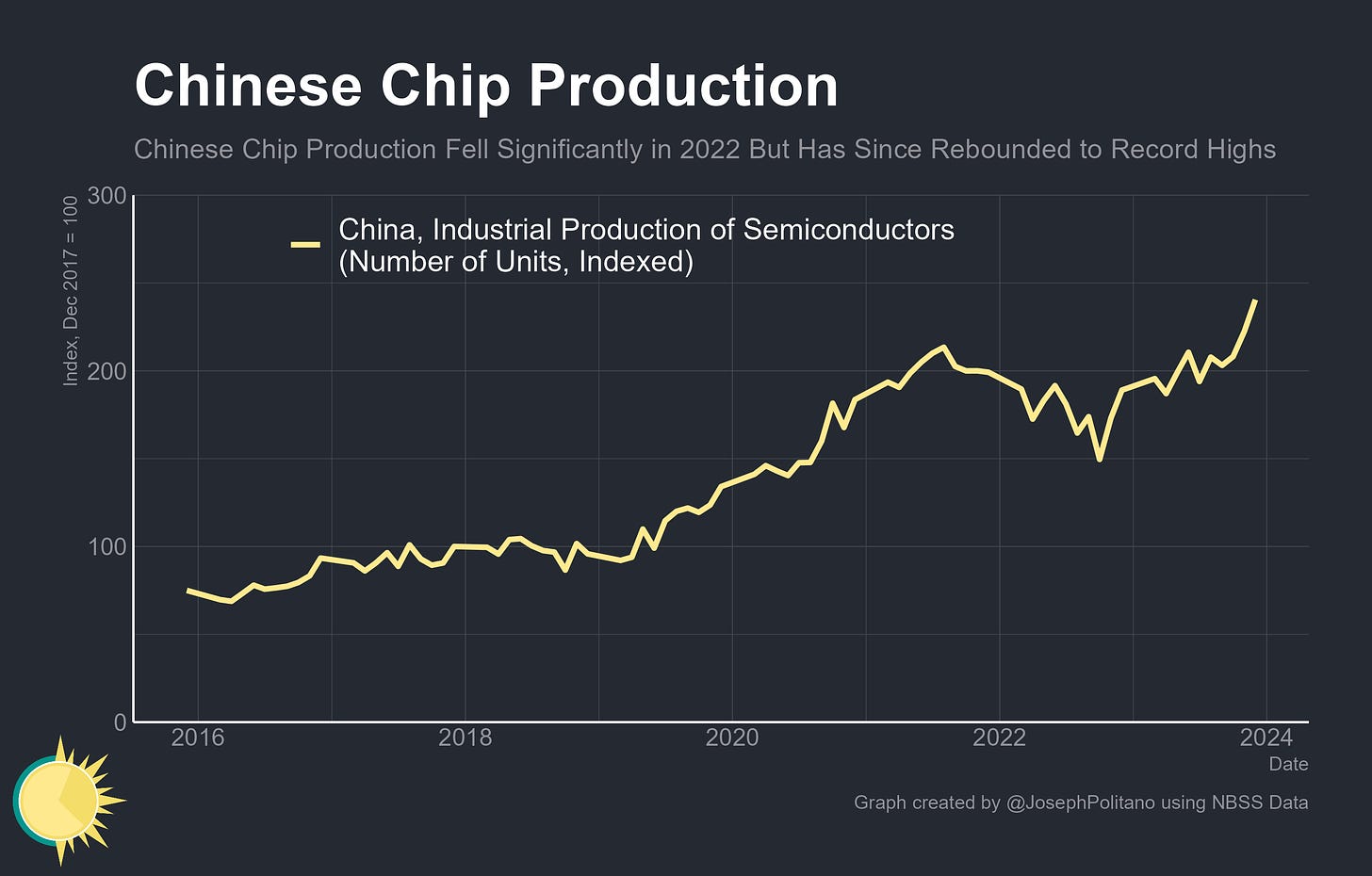

Meanwhile, Chinese production of semiconductors has also rebounded to new record highs after already more-than-doubling between 2018 and 2021 (note the change in the y-axis scale, but also that China measures its chip production purely as the raw number of units unadjusted for quality). Those production levels remain low relative to the nation's total industrial needs, both for domestic consumption and export-oriented demand, but they are helping to keep a lid on import growth. Chinese firms are even steadily working to gain high or dominant market share in categories of “foundational” older-generation chips which nevertheless remain necessary to the manufacturing of electric vehicles, consumer electronics, household appliances, and much much more. That would complement their existing industries and provide a springboard to move even further up electronics value chains—while giving them more leverage in possible future chip trade disputes. The country is also rapidly expanding into the design space, with the number of firms and their revenue multiplying in an area where China once lagged significantly, highlighting just how widespread growth is throughout the national semiconductor industry.

Conclusions

The Chinese government and military have already been able to acquire some of the highly-coveted NVIDIA A100 and H100 chips American sanctions were designed to keep them from buying, and NVIDIA is rumored to be making more chips explicitly for the Chinese market with capabilities designed to come just under new US export restrictions. The US is continually playing whack-a-mole to wrangle the trading firms that enabled those acquisitions, as well as other possible methods of circumventing sanctions like via cloud computing services. America has also struggled to fully reign in foreign chip investment to China, with Korean chipmakers Samsung and SK Hynix alongside Taiwan’s TSMC negotiating essentially indefinite permission to import chipmaking equipment to their China-based factories. China’s leading domestic semiconductor manufacturer SMIC has already made an attention-grabbing breakthrough with the manufacture of 7nm chips used in new Huawei cell phones, and even though this was cobbled together using old foreign equipment and may not be ready for the limelight of long-term production it still represents a significant breakthrough that came much faster than observers expected. Plus, China is steadily reducing its reliance on imported chipmaking equipment, with domestic suppliers now eating into the market share once held by foreign firms.

In response, the US is amping up the pressure—intensifying its export restrictions, policing outbound investment in key tech sectors, and successfully pressuring the Dutch government to further limit ASML’s exports to China. Those will continue to cause real pain to the Chinese chip sector, but will also likely strengthen the PRC’s resolve to advance their own independent domestic semiconductor capacity. All of this highlights the difficult nature of managing an effective sanctions regime—they require widespread effective cooperation, they encourage rivals to sever the very economic links you seek to exploit, they’re costly to implement, and they can still end up porous. If the US continually tries to impair China’s semiconductor industry without catching up domestically it just won’t work long term—which is why so much hinges on whether CHIPS Act investments will end up being successful.

Yet the ongoing war over semiconductors again highlights the escalating cycle of expensive great power economic conflict that has come to dominate so much of economic policymaking—building out redundant capacity to fortify supply chains has significant costs, as does cutting off or redirecting bilateral trade between the world’s two largest economies. The US-China trade war has only continually ratcheted upward over time, and the level of industrial policy spending and intensity of trade restrictions in place now would have been unthinkable even 10 years ago. Both countries are currently paying those costs, and it remains to be seen if either will be able to reap rewards from victory.

You hit the nail on the head. Thanks for sharing it!

Semiconductor equipment manufacturer are amping up the production to supply to Samsung & TSMC’s facilities in China as they have 1 year permission/extension. China is building buffer/spare equipment. to run these fabs for foreseeable future (hence the inflated buying in the last 2 years)

However, equipment guys predict a sales dip once the extension gets over.

Let’s hope TSMC and Intel’s new fabs in US will be commissioned as per their plans. It’s interesting turn of events indeed!!