The US Labor Market Was Stronger Than We Thought

Updated Data Shows Strong Employment and Payroll Gains—Alongside Decelerations in Wage Growth

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 22,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

Can inflation come down without a recessionary increase in the unemployment rate? That’s the critical question facing today’s US economy.

On balance, the large batch of updated labor market data published in the last week makes that “soft landing” outcome—where inflation dissipates without a recession—more likely.

Jobs data remained extremely strong, with significant upward revisions to both employment and payrolls. Those revisions also erased perceived job losses in select key sectors that serve as leading indicators for economic activity. The unemployment rate also sank to its lowest level since 1969 and prime-age employment rates remain just 0.4% below pre-pandemic peaks.

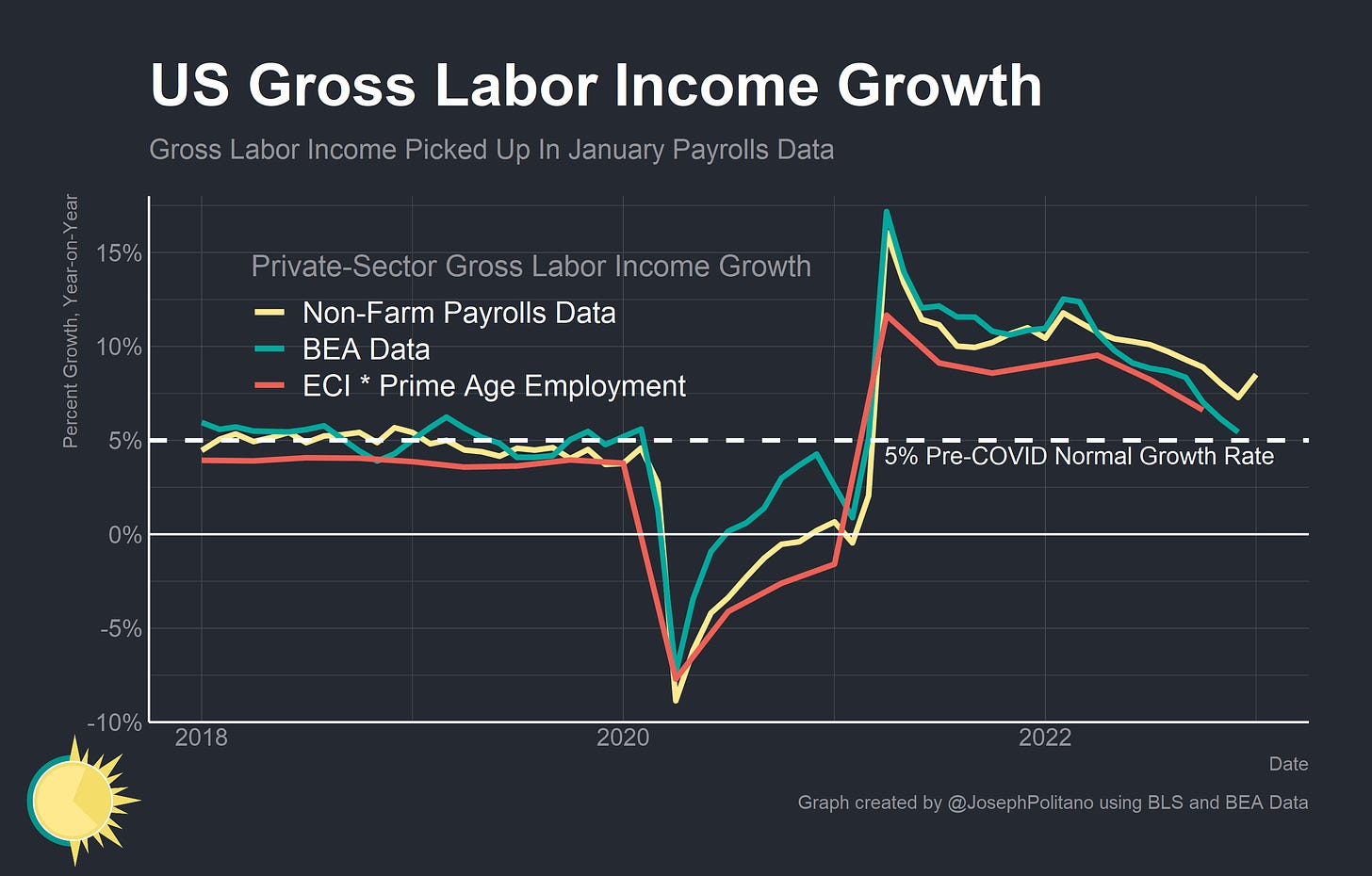

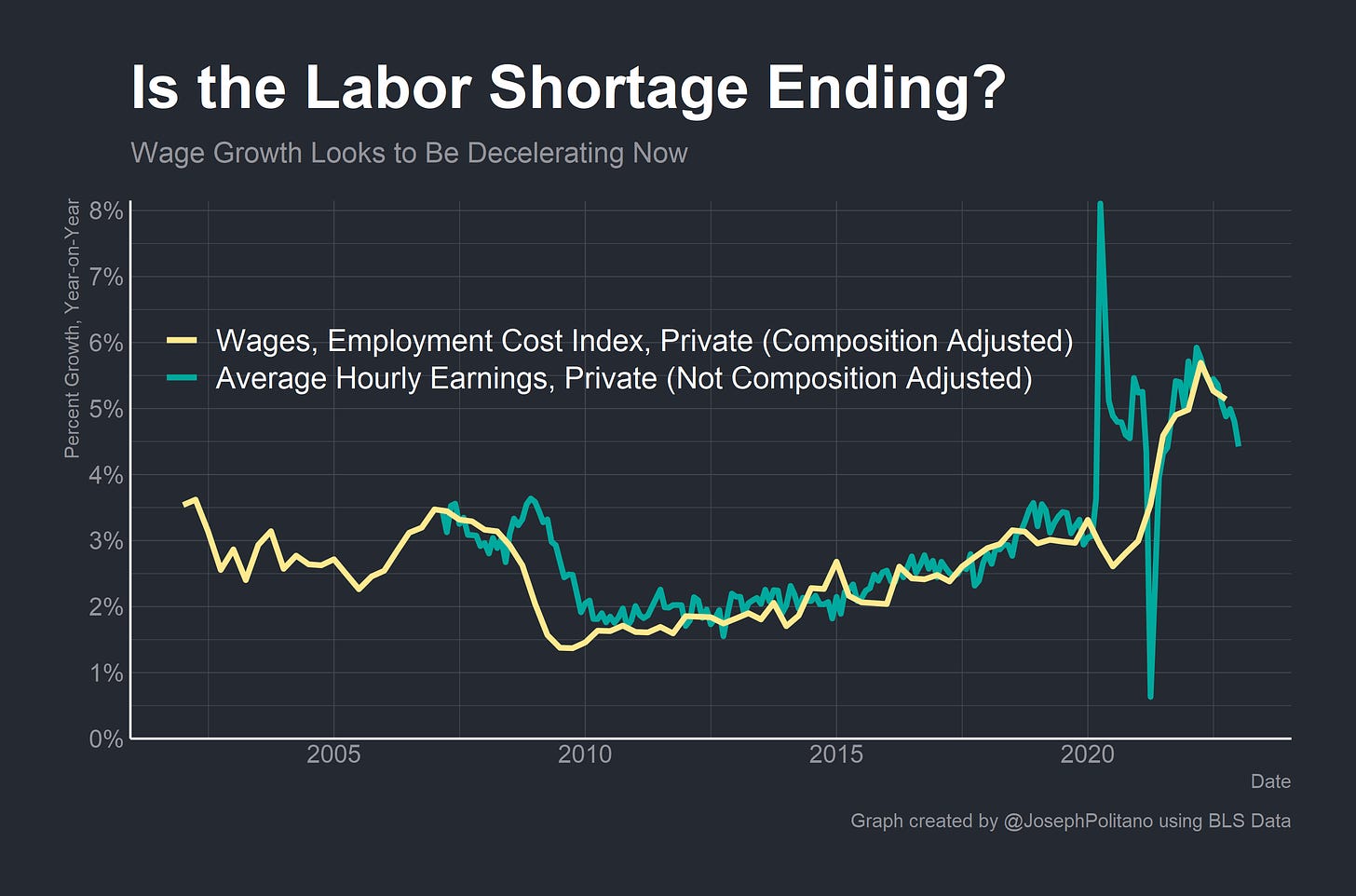

Meanwhile, wage growth continued to decelerate—with private industry wages growing 5.1% over the year ending in Q4 according to the more comprehensive Employment Cost Index, and average hourly earnings for private-sector workers growing 4.4% over the year ending in January 2023 according to payrolls data. This deceleration remains particularly stark in low-paying sectors like retail trade and leisure & hospitality.

That’s caused growth in gross labor income, the aggregate sum of workers’ wages and salaries, to substantially decelerate over the last quarter—though growth remains above pre-pandemic rates and the nonfarm payrolls number surged thanks to an unusually good January. Still, the data released this week shifts our perspective of the labor market in a way that makes a soft landing more likely—more of the growth in gross labor income is coming from net job gains, and less of it is now coming from nominal wage growth, and unemployment did not have to rise to achieve the rebalancing we’ve seen so far in the labor market. However, that also means the Fed’s job in fighting inflation is not yet over—and on the margins, they are likely to perceive the resilience in job growth as indicating the US economy can handle higher interest rates than previously believed.

The Stronger Labor Market

Yesterday’s jobs report showed the US adding more than half a million jobs in January, rapidly exceeding consensus forecasts and notching the largest monthly increase in nonfarm payrolls since July. The underlying month-to-month strength probably isn’t quite as dramatic as headline numbers suggest—employment growth was relatively weak and a lot of the payrolls strength seemed to stem from how shifts in seasonal patterns are interacting with seasonal adjustment calculations derived from older data—but it was revisions to growth over the last year that represented the largest sign of strength in the labor market.

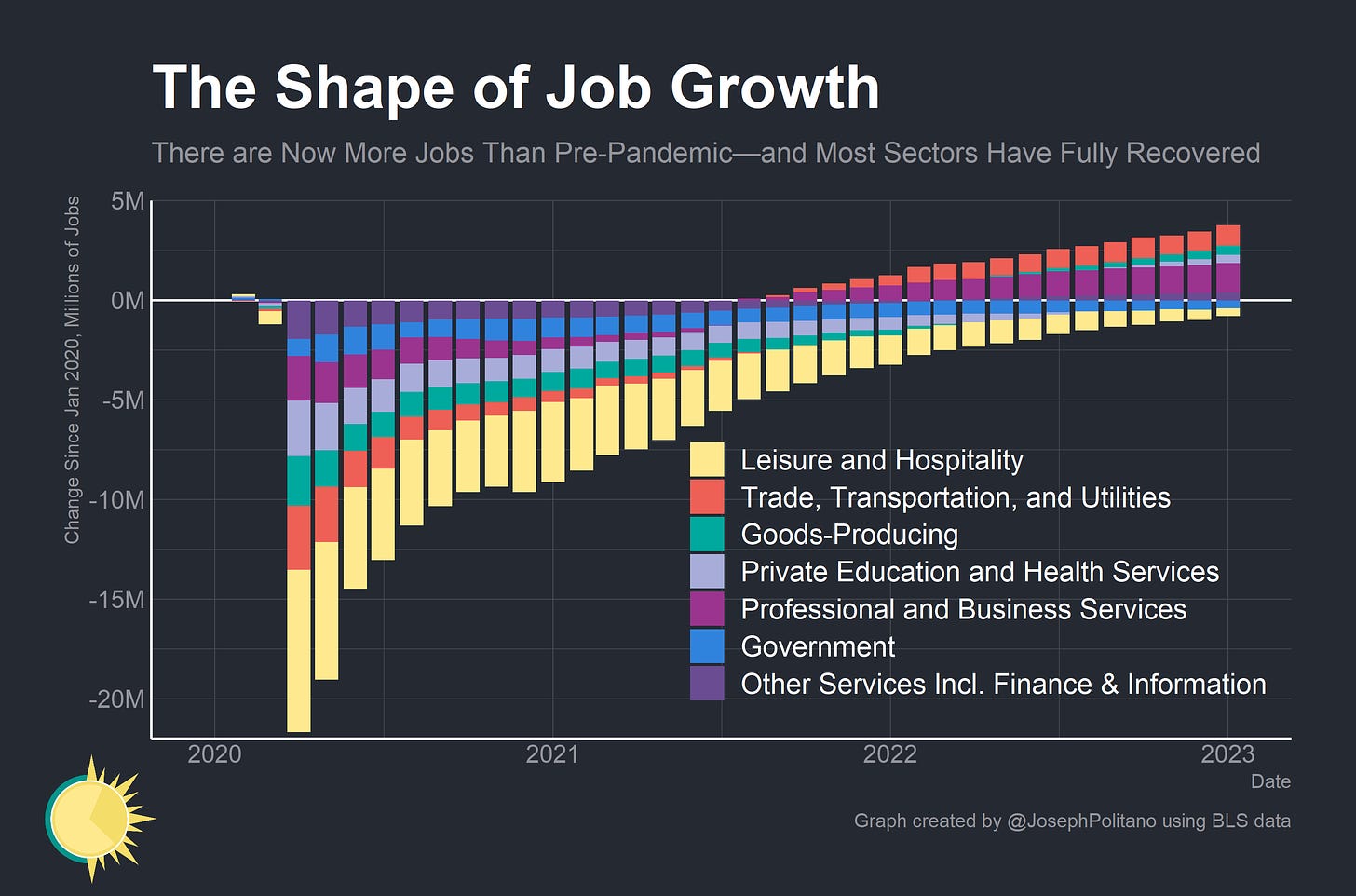

December payrolls were revised up by 813k thanks to the incorporation of comprehensive annual benchmark revisions to BLS data—meaning the US has added nearly 5 million jobs over the last 12 months. Essentially all major industry groups have seen a full employment recovery since the start of the pandemic except Leisure & Hospitality and Government (which includes public schools)—and those industries have mostly seen jobs decline as a result of higher-paying industries poaching their workers. Even healthcare services employment, one of the industries most impacted by COVID-19, has now more than fully recovered.

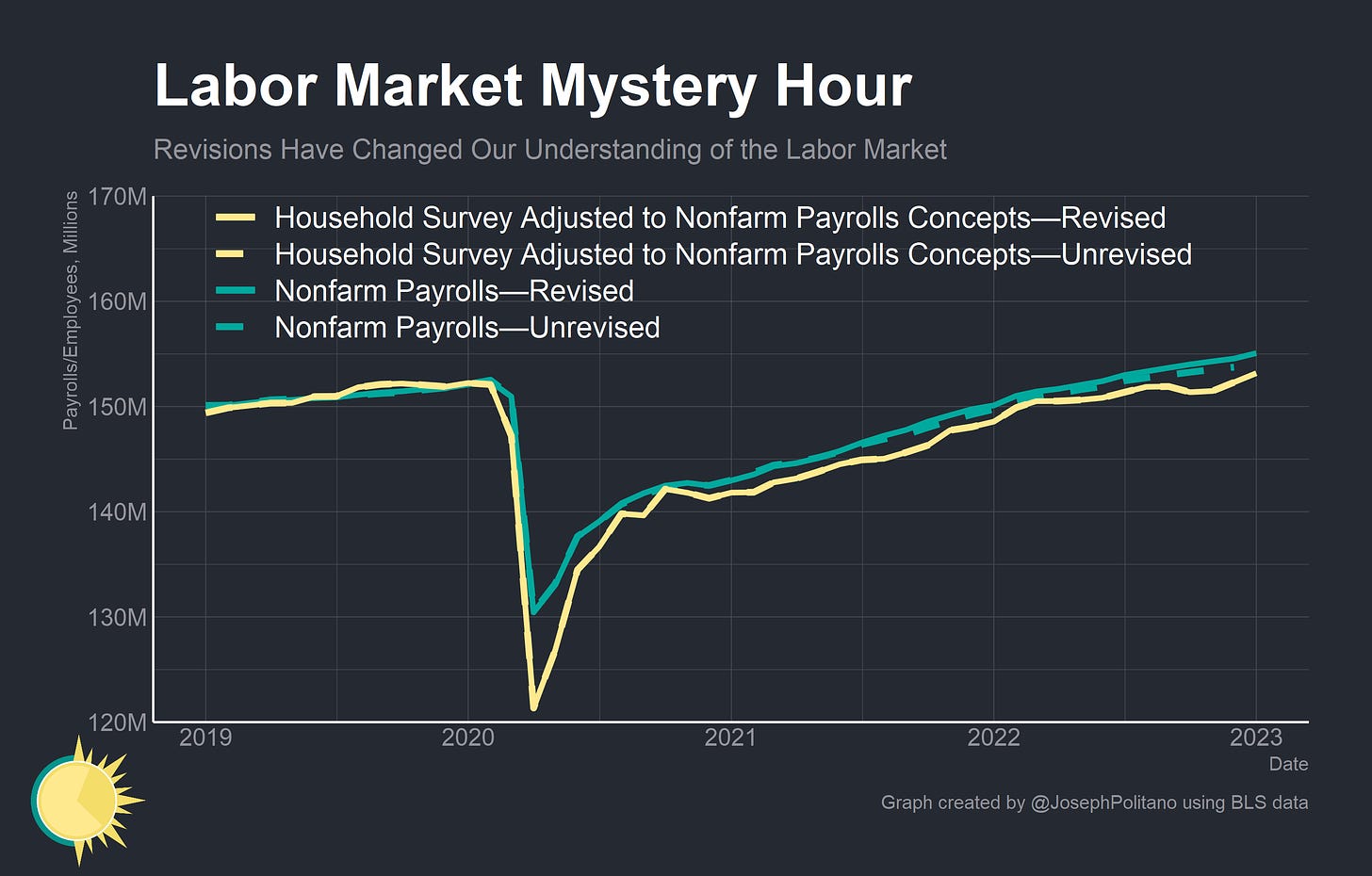

We also received updates to the population estimates that are used to weigh results from the household survey to determine levels and rates of employment and unemployment. The number of employed Americans increased by 810k thanks to these population controls (BLS doesn’t revise old household survey data with new population benchmarks, hence the large jump in January)—meaning we can now officially confirm that both nonfarm payrolls and overall employment exceed pre-pandemic levels.

Unfortunately, this jobs report did not provide easy answers to the lingering discrepancy between employment data from the household survey and nonfarm payrolls data from the establishment survey. Since March 2022, the payrolls data has been running hotter than the employment data, and since both series were revised upwards by about 800k the gap still largely persists. It’s possible this discrepancy will only be corrected at the next benchmark revision—the Business Employment Dynamics report, which is based on the same comprehensive underlying data that goes into the payrolls benchmarks, showed a net job loss of 300k in Q2 2022 that stands in stark contrast with the 1.2M job gains reported in payrolls data over the same period. Still, the discrepancy feels less pressing because both surveys now agree that employment is rising broadly.

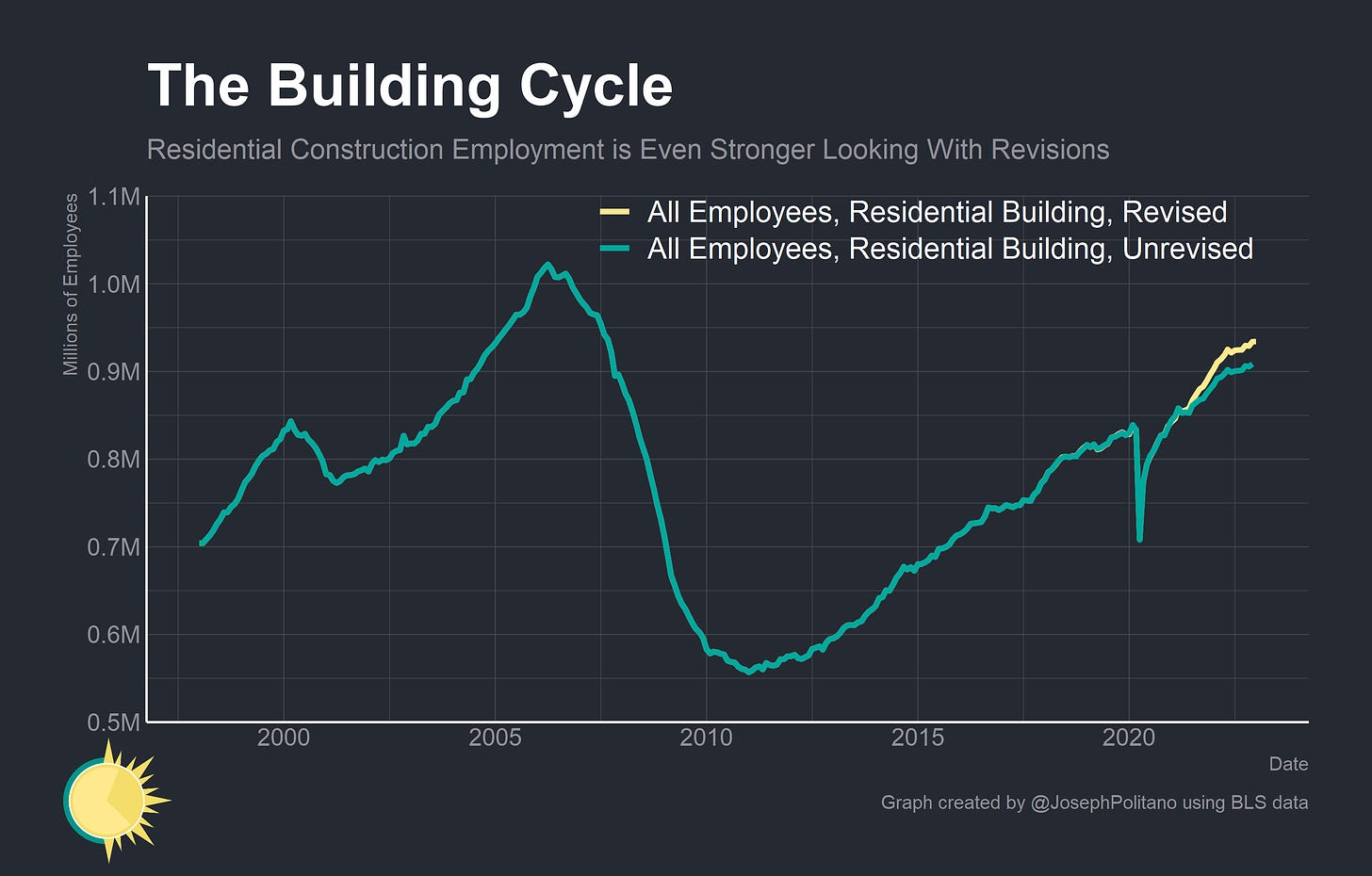

The benchmark revisions also reshaped our understanding of some of the key “leading indicators” for the labor market—sectors that tend to lead employment dynamics elsewhere in the economy or are otherwise more sensitive to overall economic conditions. Residential building employment, which before looked to be holding up moderately well despite higher mortgage rates, now looks even stronger.

Employment in warehousing and storage is also significantly larger and holding up better than previously reported. The number of jobs in the industry has practically doubled since 2017 as US e-commerce spending soared and was turbocharged by the pandemic, although the slowdown in 2022 has been palpable. Truck transportation, another key goods-related sector, has seen employment hit another record high this month.

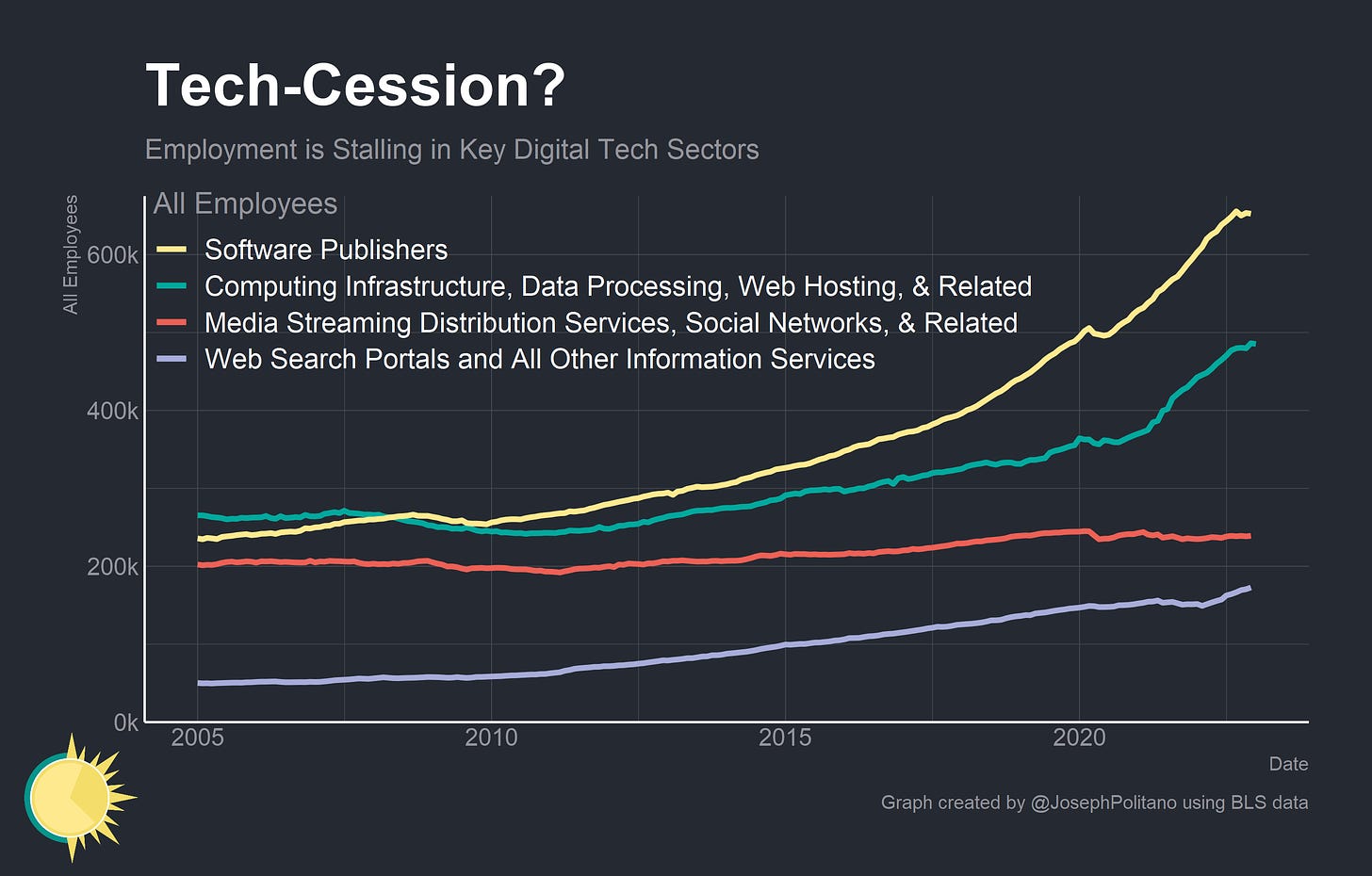

Yesterday's jobs report also saw the reclassification of many employment categories to reflect updated industry categories. About 10% of jobs were reclassified into different industries, with most of the shifts designed to better reflect the realities of employment in the retail trade and information sectors amidst the rise of e-commerce and digital services.

Critically, these updates allow us to take a closer look at the recent downturn in the US tech industry at a level of detail that was not possible before. So far, employment has stalled in many key tech sectors—especially the fastest-growing industries of software publishing and computing infrastructure—but so far overall job losses have been minimal. The bigger deal seems to be a stagnation or decline in compensation—including normal wages, stock options, and other bonuses.

Combined, it means that many of the sectors that had demand pulled forward during the early pandemic—tech, transportation, warehousing, homebuilding, manufacturing, and more—are holding up better than we previously thought. And outside these sectors, job growth and employment gains remain strong.

(Un)Employment

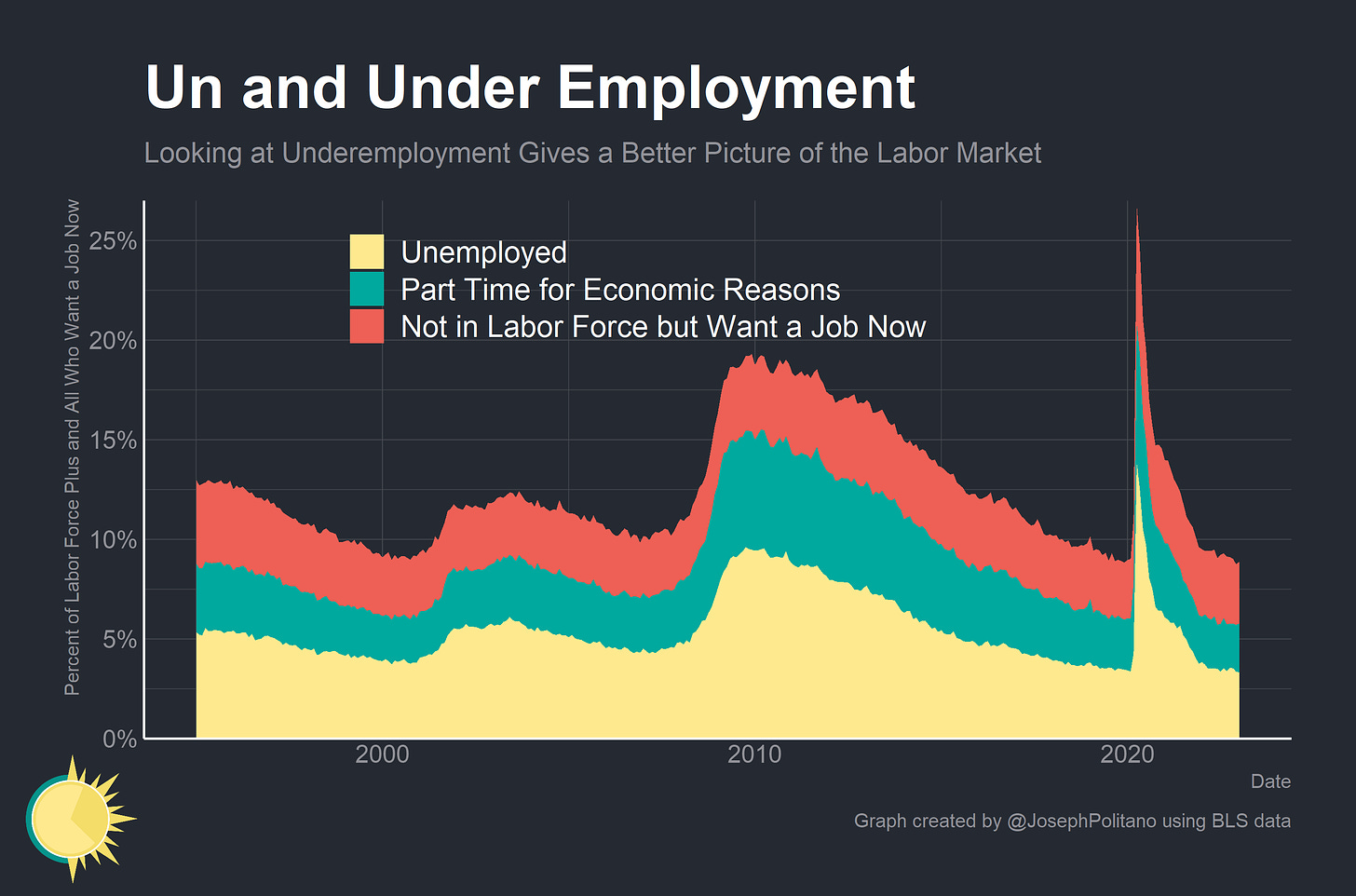

Labor market strength has now driven unemployment to the lowest level since 1969. Even if you take an expanded view, including those marginally attached to the labor force and those working part-time who want to work full-time, underemployment is at the lowest level for as long as microdata is available.

However, the broadest and most important measure of employment strength is still below pre-pandemic levels. The share of working-age adults with a job is still slightly below the 80.6% notched just before COVID, significantly below the 81.9% achieved in the late 1990s, and far below the 84%+ now achieved by America’s closest economic peers.

Still, employment gains have been extremely broad-based—the share of people with disabilities with a job is at a record high, the share of working-age women with a job is 0.2% below all-time highs, and the share of 55-64-year-olds with a job is near a record high, for example. There are still some issues impacting labor supply—an outsized number of workers are still getting sick and struggling with childcare—but the overall picture is that employment rates have stabilized at a level just below pre-pandemic peaks.

Wage Deceleration

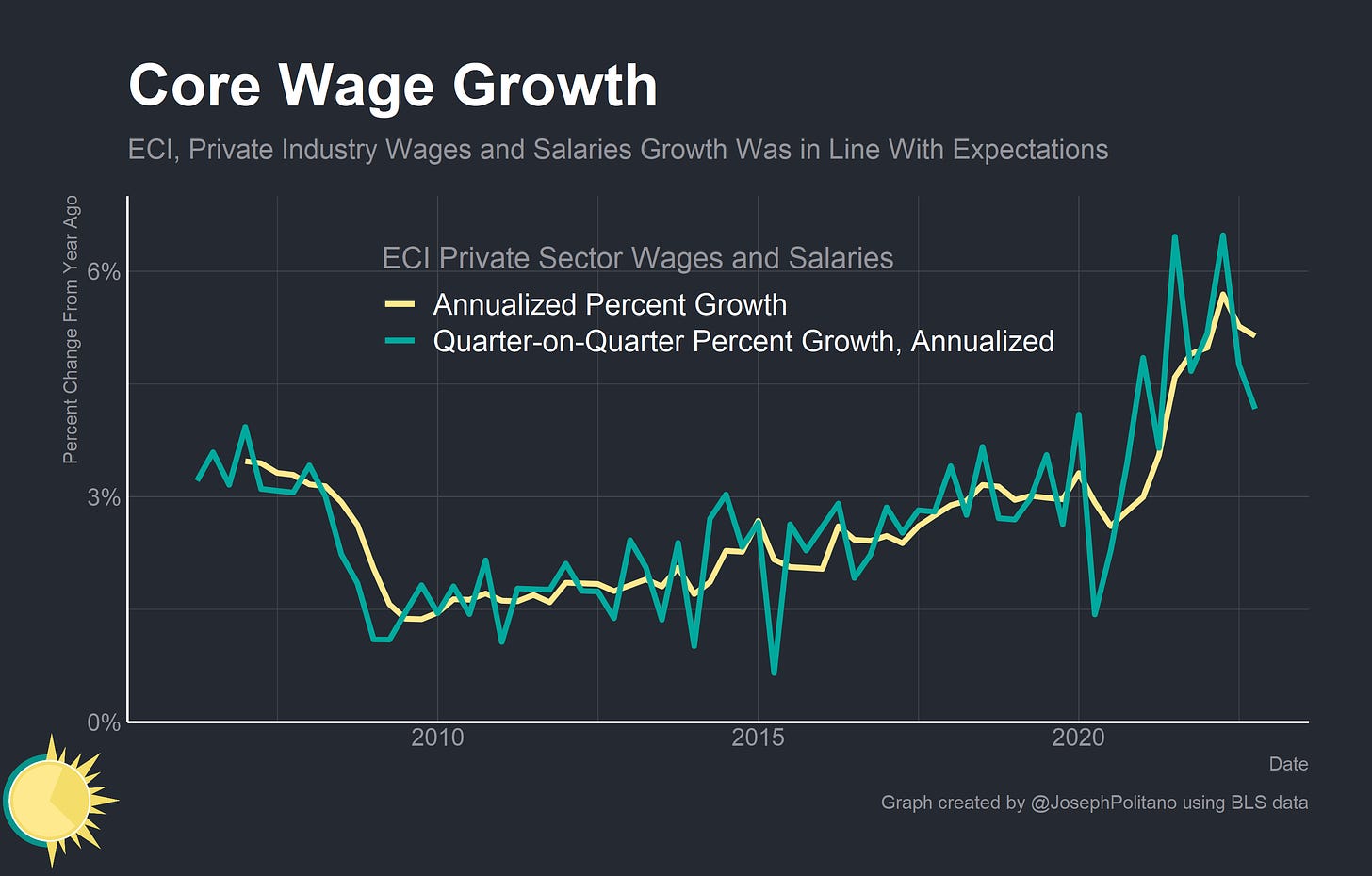

Meanwhile, comprehensive data on wages and benefits from the Employment Cost Index shows wage growth decelerating significantly over the last two quarters. Year-on-year growth in private-sector wages fell to 5.1% in Q4, coming in below consensus expectations while quarterly wage growth, on an annualized basis, grew only 4.1%. That quarterly growth rate is about consistent with the high-end of normal wage growth levels the US recorded during the strong labor markets of the 1980s and late 1990s—though obviously conclusions can’t be drawn from one data print alone.

Recent movements in the more-frequent average hourly earnings prints also suggest more wage disinflation could be on the way—although these numbers are much more volatile and have been subject to extremely large revisions recently. However, the pace of nominal wage growth likely remains slightly too high to be consistent with target inflation—the quit rate remains elevated and wage growth in posted job openings on indeed was 6.2% over the last year.

Conclusions

Tighter monetary policy changes financial conditions and economic planning almost immediately—but the effects of these changes can take a while to show up in broader economic activity and data. So far, the labor market has withstood a tremendous amount of rate hikes without the amount of contraction expected by policymakers, markets, or most economists ex-ante—and in many ways the disinflation we’ve experienced amidst labor market strength has been a relatively ideal outcome.

Chair Powell and the FOMC acknowledged the start of that disinflationary process at their meeting this week—stressing simultaneously that they know lags in the transmission of monetary policy mean much of their prior tightening hasn’t yet shown up in economic data and that they don’t believe they have done enough to contain inflation yet. As talk shifts from the pace of rate hikes to the level of terminal rates, labor market data should nudge the Fed to believe that they are making progress on their disinflationary goals, that underlying economic growth is stronger than previously thought, and that a soft landing is now marginally more likely.

Thanks Paulo!

I find it still confuses me to figure out the difference between the unemployed and those not in the labor force but want a job!! What am I missing here? This is a very confusing subject to say the least given the spectacular payrolls numbers and yet, somehow, some degree of disinflation. Thanks for a first stab and trying to sort this all out Joseph.