Tight Monetary Policy, Not Loose Monetary Policy, Has Exacerbated Inequality

Karen Petrou's NYT Article Has Monetary Policy Backwards: It Has Been Too Tight, Hurting Low-Income Americans the Most

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

I felt the need to respond to Karen Petrou's recent op-ed "Only the Rich Could Love This Economic Recovery" in the New York Times and correct the record on the relationship between expansionary monetary policy and wealth inequality. I encourage you to read the piece if you have the time so that you can properly get both sides of this argument. It is emblematic of a widespread trend among pundits on the edges of the political and economic spheres blaming monetary policy, and therefore the Federal Reserve, for the rising inequality in the United States. The story goes something like this: through ultra-low interest rates and Quantitative Easing (QE, a program where the central bank exchanges government bonds for a special type of inter-bank money called reserves) the Fed has buoyed the financial assets of the wealthy without actually improving the economy. The Fed should instead "normalize" by raising rates, taking away the proverbial punch bowl in order to lower the "inflated" value of financial assets and stop the rise in inequality.

There are two parts of this story that are critically important and that the author got exactly backwards. First, monetary policy has been too tight over the last 15 years, not too loose. This tight monetary policy was a critical cause of the great recession and contributed to the lackluster recovery in the wake of 2008. This tight policy meant that unemployment remained high and economic growth remained low, contributing to inequality. Second, there is no direct causal channel from looser monetary policy to increased stock and real estate returns. The primary chain is only that expansionary monetary policy can support economic growth and therefore indirectly increase the value of capital goods.

The Tight Monetary Policy of the Last 15 Years

The Federal Reserve's dual mandate directs it to focus on price stability, defined as 2% inflation in the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index, and full employment, a much less clearly defined term encompassing the general health of the labor market. Since 2006, policy has failed on both of these accounts: inflation has been below the 2% target and the labor market has been well below full employment. This has been because policy was too tight over that time period, not too loose.

This distinction confuses many people, as the Federal Reserve has kept interest rates at historical lows of 0% and has instituted unprecedented massive QE in order to drive down long-term interest rates. The important thing to understand is that the nominal interest rate does not tell you whether policy is "tight" or "loose." Only by looking at the interest rate in relation to inflation, unemployment, nominal GDP, and nominal labor income can you determine the stance of monetary policy.

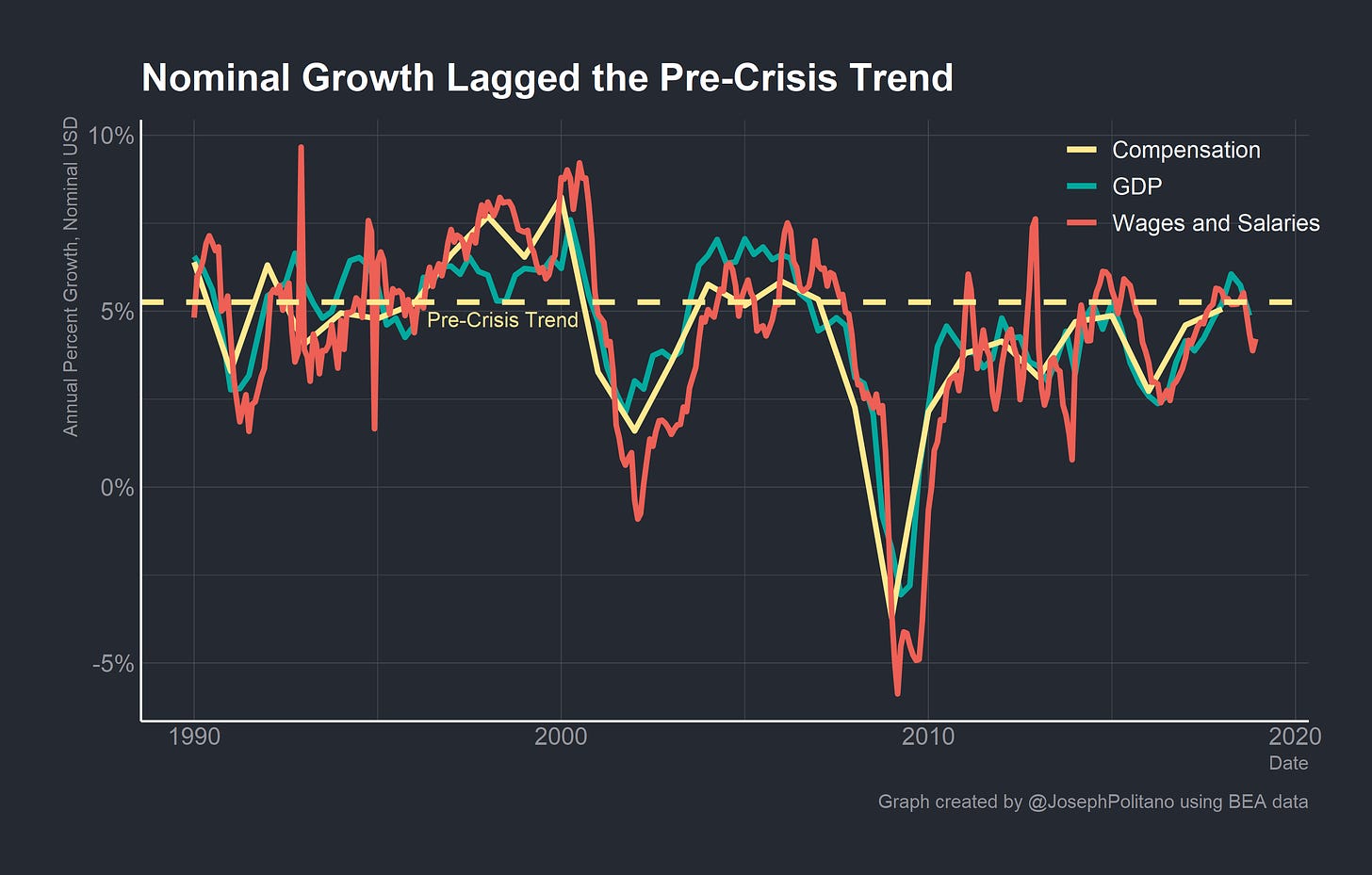

When looking at nominal GDP and labor income growth, it becomes clear that monetary policy was tight and held back growth through much of the last decade. The graph above shows the growth rates for nominal GDP, wages & salaries, and labor compensation compared with the 1990-2007 trendline for nominal compensation growth. Labor income growth lagged the pre-crisis trend significantly, only reaching the trend during brief moments before sinking back down. The weak growth in labor income dragged down GDP growth. One critical thing to note is that nominal growth tanked in 2006-2007, before the official recession started in 2008. This massive drop in income growth indicated that monetary policy was too tight before the crisis, and this tight monetary policy contributed to the rise in mortgage defaults and drop in home prices that ignited the financial crisis. In the immediate aftermath of the crisis, despite the start of QE and near-zero interest rates, monetary policy remained too tight and fiscal policy too contractionary to reach prior growth rates.

This tight policy caused what Matthew Klein dubs “the undershoot”: America broke with more than a half-century of 2.2% annual GDP growth. The country did not reach the prior growth path nor prior growth rate, and as a direct result the average American is 20% poorer than they otherwise would be. That aggregate reduction in income was primarily borne by low-income Americans, who were more likely to lose their incomes and their homes in the crisis.

Aggregate labor income remained low partly due to significant unemployment and labor force non-participation throughout the economy. This graph shows the Prime-Age Employment-Population Ratio, essentially the percent of working-age people who have jobs. This is one of the single best measures of labor market health, as unlike headline unemployment measures it accounts for "discouraged" workers who were unemployed but gave up on their job search. The Prime-Age Employment-Population Ratio has yet to reach its peak from the late 1990s, and took until the start of the pandemic to reach the pre-2008 level. Besides, as Employ America illustrated, there is no reason to believe that the late 1990s level is "maximum employment" as several of America's peer nations have even higher levels.

Finally, inflation remained below target throughout the entire 2010s. It is important to note that the Fed undershooting inflation targets can be just as bad as overshooting targets from a price stability perspective. When consumers, employees, businesses, and banks sign contracts with an expectation of 2% inflation that does not materialize it can ruin the plans and decisions of economic actors. Besides that, inflation is the speed limit of aggregate nominal demand. When nominal demand growth manifests only as above-target price increases it means that the economy may have reached its fastest possible growth trend. Conversely, when nominal aggregate demand growth cannot sustain target inflation it means that policy remains too tight and expansionary policy could increase economic growth. Raising rates or tightening monetary policy when above-target inflation is not a risk is austerity, plain and simple.

Had the US tightened policy or ended QE too rapidly, the economy would have suffered dramatically given the fragile recovery and weak aggregate demand. Indeed, the Fed aborting the 2018 rate hikes and reinstating QE in 2019 is a tacit admission that the policy tightening was unnecessary and counterproductive. In this recovery, the Fed's actions have been critical in preventing the collapse of large chunks of the American economy and have supported the rapid rate of recovery in the labor market. There is still so much progress to be made, and tightening monetary policy now would exacerbate inequality, not ameliorate it. Especially when the connection between QE and inequality is extremely tenuous.

Asset Price Inflation (Mostly) Isn't a Thing

In this section, I cannot attempt to prove a negative. That is, I do not believe I can decisively reject the hypothesis that QE and expansionary monetary policy contribute somewhat to inequality. Indeed, given that expansionary monetary policy tends to boost economic growth and economic growth tends to increase inequality (if the return on capital is greater than economic growth) I would expect expansionary monetary policy to increase inequality. Especially considering that lower interest rates, given a fixed cash flow, increases the value of assets. Instead, what I want to argue is that the posited direct causal link from QE/low rates to "asset price inflation" to increasing economic inequality that Karen Petrou and others propose is weak because there are so many confounding factors. In addition, even if there was a direct causal link from QE to inequality the best way to combat inequality is to increase taxes on the rich, not to tighten broad monetary policy.

The graph above shows the total dollar returns for stock indexes of US, European, and Japanese companies, indexed to 2006. While American companies have enjoyed exceptional returns over the last 15 years, Japanese and European companies barely returned anything at all. This is despite, as indicated on the graph, all three countries undertaking significant quantitative easing policies. The ECB conducted initial asset purchases in 2008 (although they did not qualify them as QE) and officially engaged in a large QE program when Mario Draghi became Chair. The US first started QE during the financial crisis, tapered purchases in 2014, and resumed them in 2019. Bank of Japan has been undertaking QE for decades with limited effects on their stock markets, which have hardly recovered from the 1989 crash. In fact, the Bank of Japan has been buying large amounts of ETFs - baskets of Japanese stocks - since 2012. Even these direct purchases have barely increased the prices of Japanese stocks!

In reality, stock market returns are defined by a combination of interest rates, cash flows, and risk. Lowering interest rates and expansionary monetary policy increase valuations through the interest rate channel and, by increasing economic growth, through the cash flow channel. Risks are much more heterogenous but should be thought of akin to the famous Fama-French 5-factor model: market risk alongside the risk of future profits, the risk of conservative investment, the risk of small firms, and the risk of ‘value’ firms. While European and Japanese companies have endured in a QE and low-interest environment for long periods of time, they have not enjoyed the outsized returns of the US because of confounding risk factors. Tight monetary policy (growth and inflation in the EU and Japan have been lower than in the US) has decreased corporate cashflows and the profitability risk factor for these companies, dampening valuations despite low interest rates. QE alone is insufficient to induce a rise in stock market prices without the economic growth and associated rising profits of appropriately expansionary monetary policy. It is also worth pointing out that, due in part to the unique business and economic environment, the tech titans Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, and Facebook all started in the US.

Stanford economist Hanno Lustig pointed out that high net worth households have more duration in their portfolios, meaning that they tend to have longer-dated financial assets that benefit more from increased valuations when long-term rates decrease. This is true, but paints a rather incomplete picture of the situation. For one, fixed income has cash flows that are, well, fixed. If an investor buys a 30 year bond at 2% interest and rates decrease to 1%, the value of the bond on the secondary market increases while the actual coupon paid by the government remains the same. If the investor holds to maturity the change in interest rates does not affect them - they can only profit by selling the bond early. However, buying a long-term bond, the riskiest kind of government bond, and attempting to rapidly sell it is a form of high-risk trading and the possibility of outsized returns reflects this fact. Most long-term bond investors instead buy and hold the bonds for their stable returns, and many are frustrated by QE precisely because it lowers the returns on those bonds. In essence, the returns to capital (including bonds and stocks) tends to decrease with QE even as valuations increase.

Though Karen herself does not use this phraseology, her arguments mirror that of people who accuse the Fed of creating “Asset Price Inflation.” The line of reasoning goes that while QE and low rates have not increased consumer inflation, they have inflated the value of financial and capital assets like stocks, bonds, and housing. I hope I have demonstrated why the idea that QE artificially boosts stock and bond prices is misguided, and I hope that my prior blog posts have shown that the majority of the increased price of housing is due to decreased housing supply. Nevertheless, here is Matthew Yglesias explaining why the whole concept of “Asset Price Inflation” is not coherent.

But while the price of a Tesla is in a consumer index and the price of Tesla’s machines is in the Producer Price Index, the price of Tesla stock is not in any inflation index. Why not? Well, because it’s not the price of anything in particular. It’s just a financial claim. It’s not like investing in oil futures where there’s a physical barrel of oil underwriting the asset. Of course, Tesla has physical assets. But the prices of those assets are already in the GDP Deflator.

And if you think about other financial assets, you’ll see it doesn’t work. When interest rates fall, the price of old bonds with the old interest rates goes up. Except this actually happens so mechanically that the way we talk about bonds is in terms of their “yield” — which is to say their interest rate relative to their face value. So when interest rates go down, yields fall. That way you can compare different bonds to each other in a meaningful way. But then you’re just in tautology territory — low interest rates are identical to high bond prices; they’re not “causing bond price inflation.”

If you believe there is a bubble in financial markets, it is best to just say so rather than claim “asset price inflation.” Bubbles are primarily social phenomenon though, driven by herding behavior and unsustainably accelerating returns rather than monetary policy. The dot-com bubble and housing bubble both occurred during times of higher rates and tighter monetary policy, and the only thing that tight monetary policy accomplished in 2008 was ensuring that the bubble left most of America in shambles rather than remaining in the financial system.

Conclusions

The stock market is a great signal of economic growth, but not a great engine of economic growth. That is to say, because the valuation of companies hinges largely on the health of the economy and because the stock market is one of few market-driven forward-looking indicators it is an invaluable tool in evaluating the economy. However, since so few Americans have significant wealth invested in the stock market the returns from any increase in share prices accrue mostly to the wealthy. Fundamentally, we should be cheering on the recent bull run in the US stock market as representative of successful investments by companies and individuals and successful policy by the government in combating the recession while acknowledging that most Americans do not meaningfully benefit from the stock market.

The answer, however, is not to tighten monetary policy in the immediate aftermath of an economic crisis. Tightening right now would mean boosting unemployment, cutting income growth, and putting more Americans in fragile financial positions. As Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari would say, most Americans’ single most valuable asset is their job. Taking that away from them is no path to greater equality.

Instead of attempting to control income and wealth inequality through the Federal Reserve, we should give that job to the Federal government. Through progressive consumption, income, and even possibly wealth taxes we can fund income support and social programs that redistribute the wealth from a rapidly growing economy. High-income countries other than the United States tend to have less inequality precisely because they engage in more progressive tax and social programs, not because they intentionally pursue bad monetary policy in an effort to lower the wealth of the top 1%.

Like most bright spots who write about “policy” you do it from a point of view of pure central planning, not understanding how markets work. You look only at how lower rates affect consumer demand and financial asset prices, completely ignoring the supply side and the fact that persistently declining rates over decades creates DEFLATION in manufactured goods.

That may seem desirable while it’s happening but leads to disaster.

Every time rates tick down a business is incentivized to finance another round of production. If they don’t their competition will, gaining market share. When supply is added as the result of suppression of rates and not natural demand, it drives down prices and compresses profit margins over time.

Yes, prices have risen (2% inflation “mandate” of the Fed) due to government compliance measures, taxes and other fees and regulations. So-called “useless ingredients” adding costs to production. The cost of production of milk has decreased 90% in 40 years, but prices are up because of these useless ingredients.

So when cost inputs finally rise above profit margin because of higher rates or more useless ingredients, marginal businesses can’t finance more production and begin liquidating. Less supply, higher prices. The public begins to question the future availability of products and they replace the bank balance with the pantry balance because there’s zero incentive to keep money in a bank with rates so low anyway.

Rates remaining below the time preference of the saver/consumer and profit margin of the marginal producer leads to more demand and less supply. The bigger players in the commodity markets have clearly already recognized a tipping point given the persistent backwardation in major commodities like

-corn

-coal

-natural gas

-soybeans

-lean hogs

-oil

-copper

-cotton

Persistent backwardation in these commodities at the same time means it is not a supply chain issue. Market actors are preferring to take physical delivery now instead of booking a guaranteed profit taking delivery in the future. They are essentially rejecting the US dollar, just like the saver/consumer who replaces the bank balance with the pantry balance.

Sociopath central planners can manipulate for a while but the market always has the final say. Always.

This is basic economics from a guy named Carl Menger. But I’m sure you’ve never heard of him.