Understanding Inflation Expectations

Inflation Expectations are Rising—Does That Mean Inflation is Here to Stay?

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 12,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

Note: Last week I wrote about the Trillion-dollar gap between GDP and GDI. Matt Klein over at The Overshoot has figured out another part of the solution—overestimation of wages is likely driving up GDI. I encourage you to read his research if you can.

In Argentina, annual inflation is running above 60%. The central bank and central government are trying a litany of policies, conventional and unconventional, to get inflation under control—but Argentinians aren’t buying it. After decades of high inflation, people do not trust the authorities and expect inflation to persist at its extremely-high levels. Workers must renegotiate wages frequently, consumers rush to make major purchases, businesses are forced to constantly revise prices upwards, investors forecast significant devaluation of their peso holdings, contracts build in high expected inflation, and saving is often done in dollars or other currencies. People expect inflation to be high, they take individually-rational actions to protect against inflation, and the cumulative effects of those actions keep inflation high. Getting inflation down in Argentina requires reducing inflation expectations—a difficult task in a country without credible institutions.

Today, inflation is high in countries across the world. In the United States, reducing annual inflation from its current level of 8.5% is the Federal Reserve’s top priority. Their biggest worry is that rising prices will raise inflation expectations and reduce Fed credibility—making the job of getting inflation down even harder.

As former Chairman Paul Volcker put it at the height of the Great Inflation in 1979, "Inflation feeds in part on itself, so part of the job of returning to a more stable and more productive economy must be to break the grip of inflationary expectations.”

Jerome Powell, Speech at Jackson Hole Symposium

The reference to Chair Paul Volcker is intentional—the 1970s are the quintessential example of inflation expectations unanchoring. As prices continually accelerated throughout the decade consumers, businesses, households, and workers began to expect that inflation would permanently remain high. Volcker re-anchored inflation expectations by raising interest rates so high that he essentially orchestrated a recession—and the ensuing Great Moderation of inflation is largely attributed to lower inflation expectations. Fears of a 1970s reenactment make recent rises in household inflation expectations especially concerning to Chair Powell.

However, inflation expectations are much more complicated than they initially appear. Households’ inflation expectations were not that well-anchored even during the Great Moderation, people are not as rational as much of the theory suggests, and the causal mechanisms that transmit higher household inflation expectations to higher inflation can be messy. Even businesses did not have well-anchored expectations—and though the causal mechanisms by which higher business inflation expectations cause higher inflation are clearer they are no less complex. Measurements of inflation expectations derived from financial markets and professional forecasters tend to carry more certainty and information, but also lack much of a causal explanation for inflation and need to be interpreted carefully. Inflation expectations remain critical for forecasting and controlling inflation, but they require rigorous analysis to be properly understood.

What Were You Expecting?

The general outline of conventional macroeconomic theory on inflation dynamics is something like this:

In the short run, inflation dynamics are determined by policy and business cycle fluctuations

In the long run, inflation dynamics are determined by inflation expectations

The role of a central bank is to manage short-run fluctuations to ensure that long-run inflation expectations remain anchored. If short-run inflation varies but central banks can credibly manage inflation expectations then long-run inflation will remain on target. If inflation expectations drift upward then the central bank has lost credibility and may have to inflict significant pain on the economy to regain that credibility

There’s some value in this story—nobody would say that the double-digit inflation Argentina has experienced for many years comes purely from supply-chain disruptions and people generally agree that the Federal Reserve carries more credibility than the central bank of Argentina.

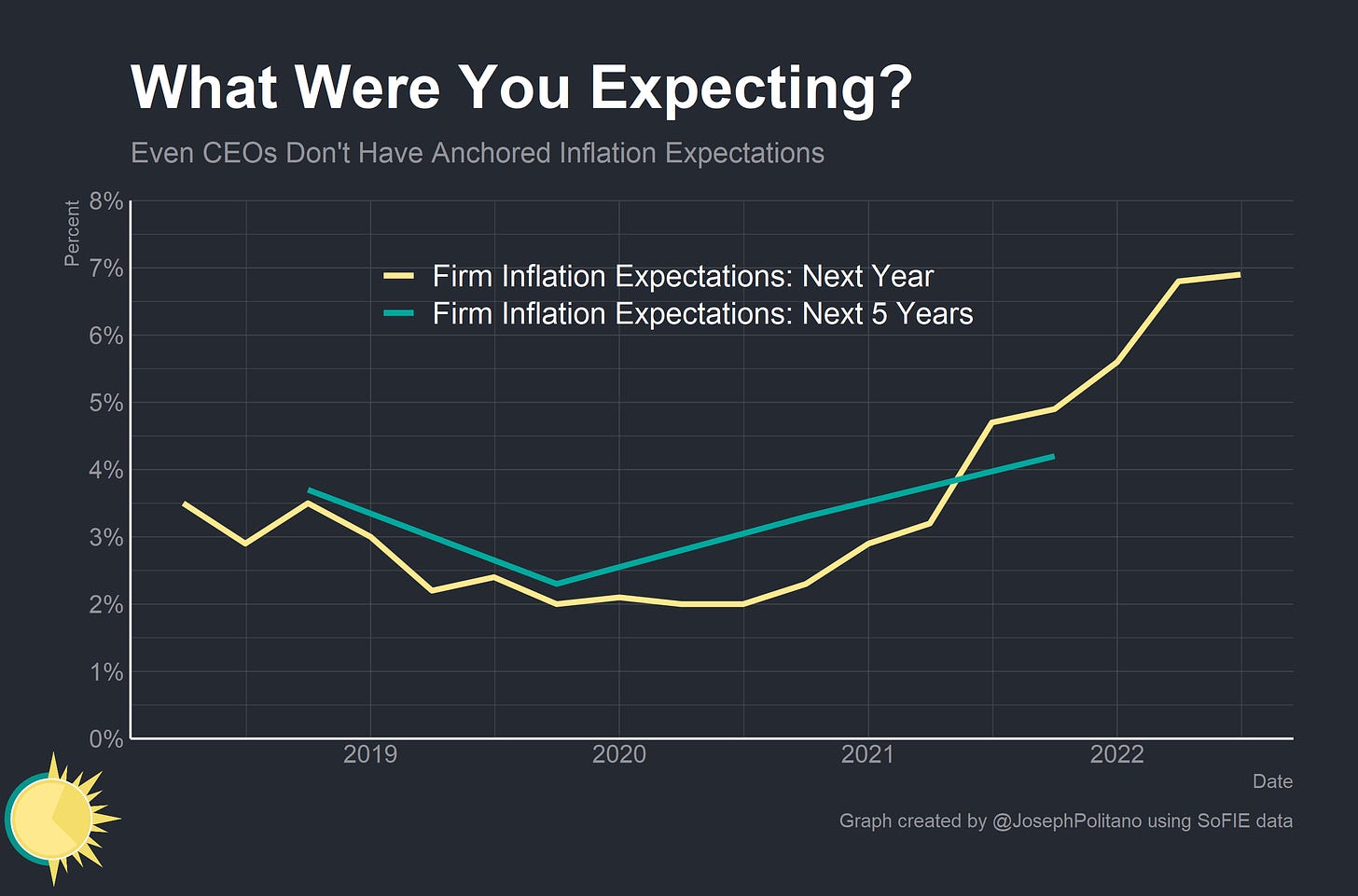

At the same time, though, household inflation expectations are not as well-anchored as they initially appear. Even during the Great Moderation, between 20-30% of respondents to the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers exhibited high uncertainty in their inflation forecasts according to Binder (2017)—and that number is rising now. Dispersion in household inflation forecasts is also high within the New York Fed’s Survey of Consumer Expectations—and in both cases forecasts were consistently biased upwards during the 2010s. Consumers also revise their inflation forecasts extremely frequently, as often as 3-4 times in 6-month periods (Binder 2017) (although there is evidence this partially reflects learning-through-survey effects (Kim 2022)). In other words, households tended to forecast higher-than-target inflation in aggregate, exhibited significant uncertainty in their forecasts, and revised their forecasts often, all of which are inconsistent with strongly anchored inflation expectations.

Households also have different ways of forming inflation expectations than rational expectations models suggest and have different beliefs about what causes or solves inflation. For example, personal life experiences tend to have an extremely strong impact on shaping people’s inflation expectations—Malmendier and Nagel (2016) show that younger people update their inflation expectations more strongly in response to recent shocks due to relative lack of experience, and D’Acunto et al (2021) use grocery spending microdata to show that consumers’ inflation expectations are sensitive to large price changes in goods they purchase at high-frequency. Andre et al (2022) show that consumers on average believe an unexpected increase in interest rates—which the Federal Reserve uses to lower inflation—would increase inflation. Households also tend to report lower inflation expectations when a political party they agree with is in power (Gillitzer, Prasad, and Robinson 2017)—and some of the biggest shocks to reported consumer inflation expectations in modern history come from political events like the impeachment of President Trump or the election of President Biden (Binder, Campbell, and Ryngaert, working paper).

You can square a lot of this by saying that households are rationally inattentive toward inflation, have a supply-driven view of the world, rely on good-bad heuristics, and tend to overestimate inflation due to negativity bias. Rational inattentiveness simply means that, with limited attention to devote to any one topic, many households do not focus on inflation when it is relatively low—forming rough estimates based on personal experiences instead of carefully-crafted forecasts driven by painstaking research. The good-bad heuristic simply means that many households tend to presume that positive/negative developments will lead to improvement/deterioration across a variety of economic indicators—hence why the election of preferred candidates will have good effects (lowering both inflation and unemployment) and raising interest rates will have bad effects (raising both inflation and unemployment). The supply-driven view means households perceive shocks as being caused by supply issues and driving further supply issues; for example, rising gas prices are usually perceived by consumers as a negative sign even though strong demand or weak supply could be driving the price change. Finally, negativity bias leads people to be systemically pessimistic in their expectations and forecast higher inflation than professionals—hence why consumers, in aggregate, have never forecasted real income increases in the history of the University of Michigan survey despite decades of real wage growth.

However, when inflation is high (as today) consumers clearly respond—paying more attention to inflation, revising their inflation expectations upward, and updating their economic outlook. The main next question should be how, if at all, do rising household inflation expectations causally increase inflation?

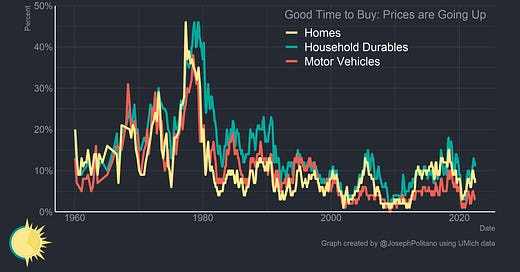

There are many ways this could happen theoretically—households with higher inflation expectations might demand higher wages or (in countries/eras with stronger collective bargaining) push for robust cost-of-living adjustments. They might make financial decisions like investing in physical assets, saving in another currency, or purchasing inflation hedges. While these, and others, are plausible causal mechanisms for inflation expectations to increase inflation, most of the literature focuses on intertemporal substitution—especially of durables. For example, if consumers have higher inflation expectations they could plausibly rush to buy cars, fridges, or homes before prices or real interest rates go up—thereby increasing demand and contributing to the very inflation they feared. This was a core part of the dynamic in the 1970s—consumers expected prices to increase and so were more willing to bid up goods, especially durables.

There is some good empirical evidence backing this idea up, too. Binder and Brunet (2020) show that at the start of the Korean War—when interest rates were held constant by the Fed-Treasury Accords—present durable and total consumption increased with expected inflation. D’Acunto, Hoang, and Weber (2020) show that VAT increases in Germany increased inflation expectations and willingness to spend on durables. Both those papers surround non-traditional inflation expectations shocks, though—the possibility of wartime price controls and unexpected tax increases—not interest rate hikes.

In more recent times, Duca, Kenny, and Reuter (2018) show that higher inflation expectations are associated with a higher chance of making major purchases across the Euro area, especially when interest rates are at 0% or lower. Ichiue and Nishiguchi (2014) show higher inflation expectations pull forward total consumption in Japan and Crump et al (2015) show a similar effect in the US.

The literature, though, is not in perfect agreement. For one, consumers might have higher inflation expectations but may be unable to act on them. A broke college student may rightly believe that home prices will increase due to inflation—but no bank will issue her a mortgage to act on those expectations. For two, the good-bad heuristic strikes again—consumers who expect higher inflation tend to also expect higher unemployment and exhibit higher economic uncertainty, both of which tend to make them less likely to make large purchases and more likely to save out of precaution. Whether higher inflation expectations causally increase inflation seems to depend on whether worries about rising prices win out over worries about deteriorating economic conditions.

Bachmann, Bergs, and Sims (2014) show zero or negative effects of higher inflation expectations on willingness to spend on durables, partially driven by households’ beliefs that higher inflation portends worse economic times. Binder (2017) also finds that more uncertain consumers are less willing to spend on durables. That’s particularly relevant today because consumers rate their uncertainty very high—and rate buying conditions for all major purchases at or near all-time lows.

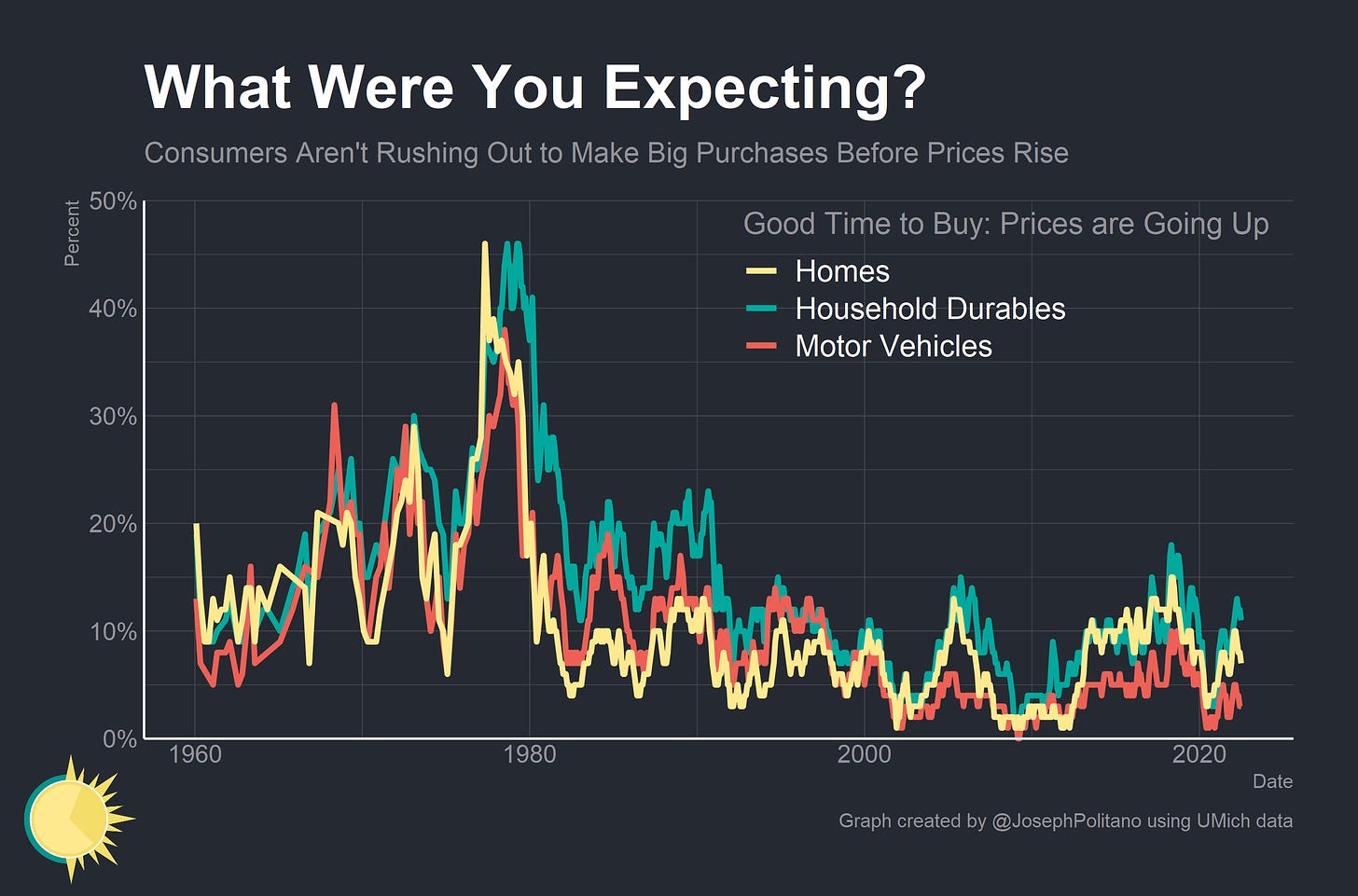

That’s the strange disconnect of today’s household inflation expectations data—consumers rate their year-ahead inflation expectations at a 40-year high and their long-run inflation expectations at a 10-year high, yet are unlikely to say it’s a good time to make major purchases in advance of price hikes. This is likely partially because prices for household durables, cars, and homes have already risen so dramatically—but it’s also partially because consumers fear that unemployment will rise and other economic conditions will deteriorate.

Firm, Not Anchored, Expectations

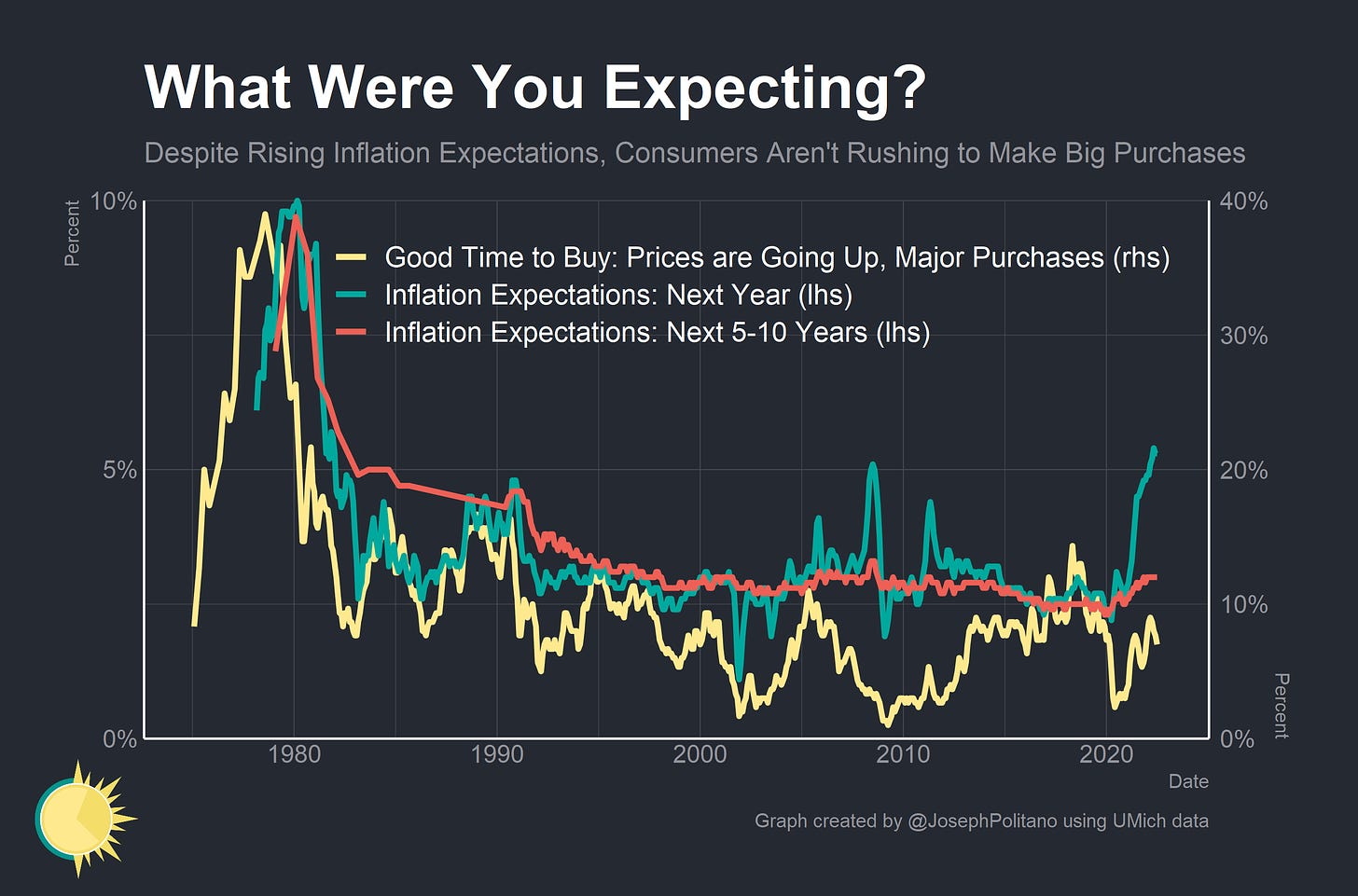

Okay, so household expectations may be messy—but are business expectations any clearer? After all, business leaders should theoretically be less prone to the kind of inattentiveness that plagues consumers and may have a better grip on pricing dynamics given their jobs.

The answer, unfortunately, is no. Firms exhibited the same kind of rational inattentiveness as consumers—back when inflation was low, most simply did not pay attention to it:

What lies behind this lack of anchoring in firms’ inflation expectations? One factor at work seems to be systematic inattention to monetary policy: we find that most CEOs are unaware of the Federal Reserve’s inflation target. The fraction of CEOs that correctly identifies 2 percent as the inflation target is less than 20 percent. Nearly two thirds of CEOs are unwilling to even guess what the target is. Of those who dare, less than 50 percent think it is between 1.5 and 2.5 percent. Another factor is the systematic inattention on the part of firms to recent inflation dynamics: managers disagree just as much about what inflation has been over the last twelve months as they do about what it will be in the future, even though the former is publicly and freely available.

Now that inflation is high, firms are paying more attention—and rapidly revising their expectations upward. So much for anchored expectations! Still, we’re fundamentally left with the same question we had for households: how, if at all, do rising firm inflation expectations causally increase inflation?

The causal chain here is obviously shorter; if CEOs expect higher inflation, they might bid up and stockpile intermediate inputs or raise prices for their own outputs. They might hire more workers or raise wages, increasing aggregate spending. Still, finding empirical evidence is important—but difficult

Coibon, Gorodnichenko, and Ropele (2019) find that Italian firms treated with information on inflation who subsequently develop higher inflation expectations raise their prices, borrow more, and reduce employment. When interest rates are 0%, firms raise their prices more and don’t lower employment. Somewhat similar results were found for firms in New Zealand (Coibon, Gorodnichenko, Kumar, 2018). There are obvious issues with these experiments (if firms change decisions when presented with information on inflation, why don’t they independently seek out freely-available inflation data? Can central banks achieve the same level of communication with firms as researchers, given central bank communications are mediated through media?) but they are a good place to start.

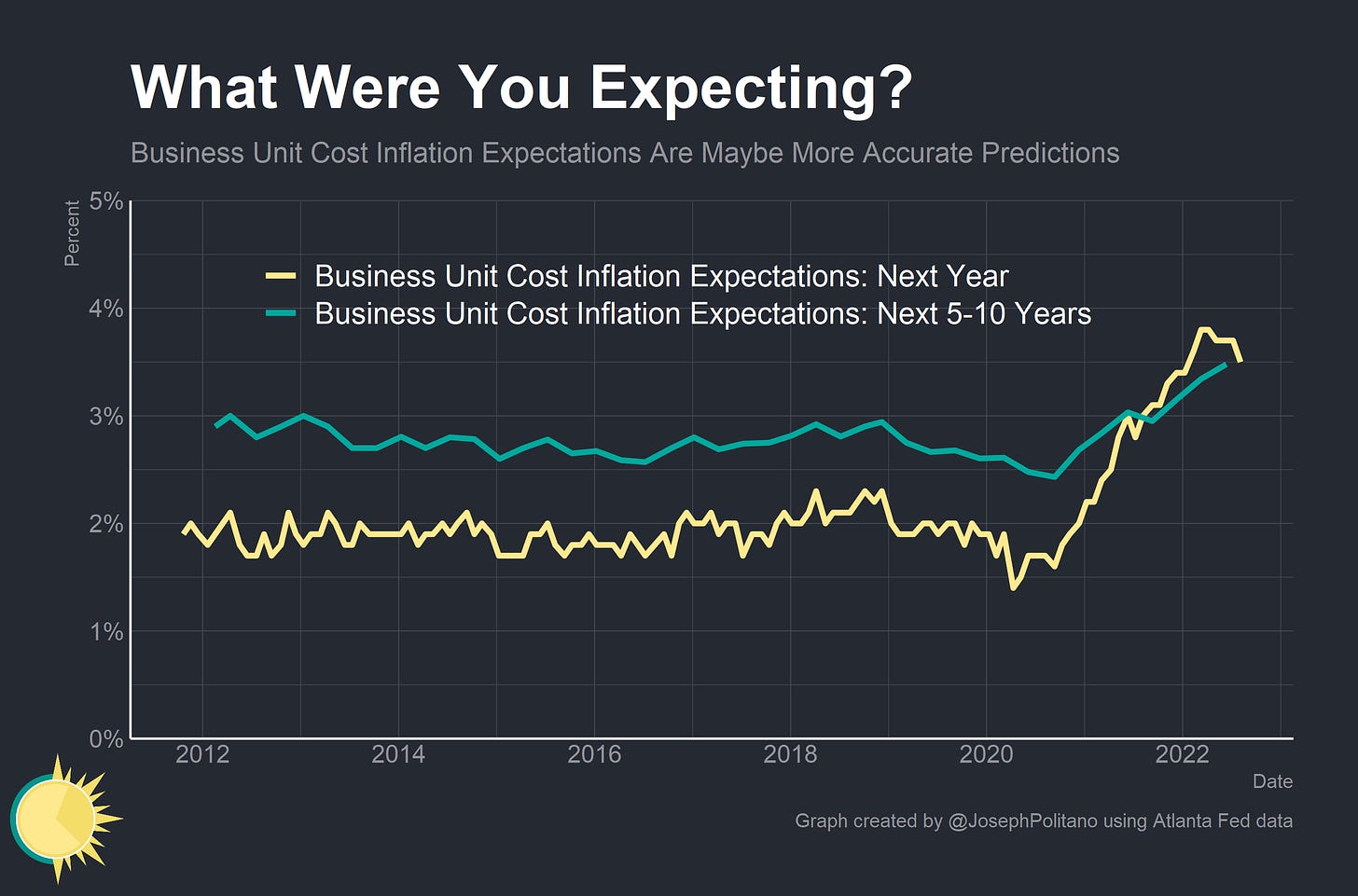

One interesting way to sidestep the rational inattentiveness problem is to ask firms about their own unit cost inflation rather than aggregate inflation. After all, is the price of an apartment in San Francisco relevant to the business decisions of a trucking company in Toledo? No—so the trucking company rationally ignores it, even though it is counted for aggregate inflation. Therefore, the Atlanta Fed’s Business Inflation Expectation (BIE) survey asks companies about their forecasted own-firm unit cost inflation rather than their forecasts about aggregate inflation, and the results are much clearer.

Meyer, Parker, and Simon Sheng (2021) show that aggregate unit-cost inflation expectations perform well in out-of-sample forecasting, do not change much when firms are treated with aggregate inflation data, and are important inputs in firms’ price-setting decisions. That might be why BIE data caught the rise in inflation before many other surveys—and why its expectations are lower than households. Worryingly, though, these inflation expectations are still elevated over short and long time horizons.

Going Pro

The last kind of relevant expectations are professional and market-based inflation expectations. The causal implications here are much smaller—while investors’ allocation decisions might drive up inflation, these metrics primarily represent forecasts of the economy rather than exogenous consumption or production decisions. In other words, professional forecasts and market-based measures of inflation expectations are primarily bets about the game rather than actions by the players. As a result, though, they should account for both the expectations and actions of players, providing a way to evaluate whether unanchored household or firm expectations may be about to increase realized inflation.

If there is a common criticism of professional forecasters it’s that their expectations are too anchored—instead of coming up with their own estimates of future inflation they simply draw a line from the current inflation rate to the Federal Reserve’s target of 2%. While it appears that way in aggregate—and professionals are clearly less uncertain and more informed about inflation than households or firms—under the surface even professional forecasters’ expectations aren’t well anchored. As recently as 2017, only about half of forecasters’ 5 or 10 year inflation expectations were within 0.5% of the Federal Reserve’s target. That number rose to 80% between 2018 and 2020—but now very few 5-year forecasts and only about 30% of 10-year forecasts are within 0.5% of the target (Binder, Janson, and Verbrugge 2022). In other words, the apparent stability of aggregate expectations again betrays substantial variation among agents.

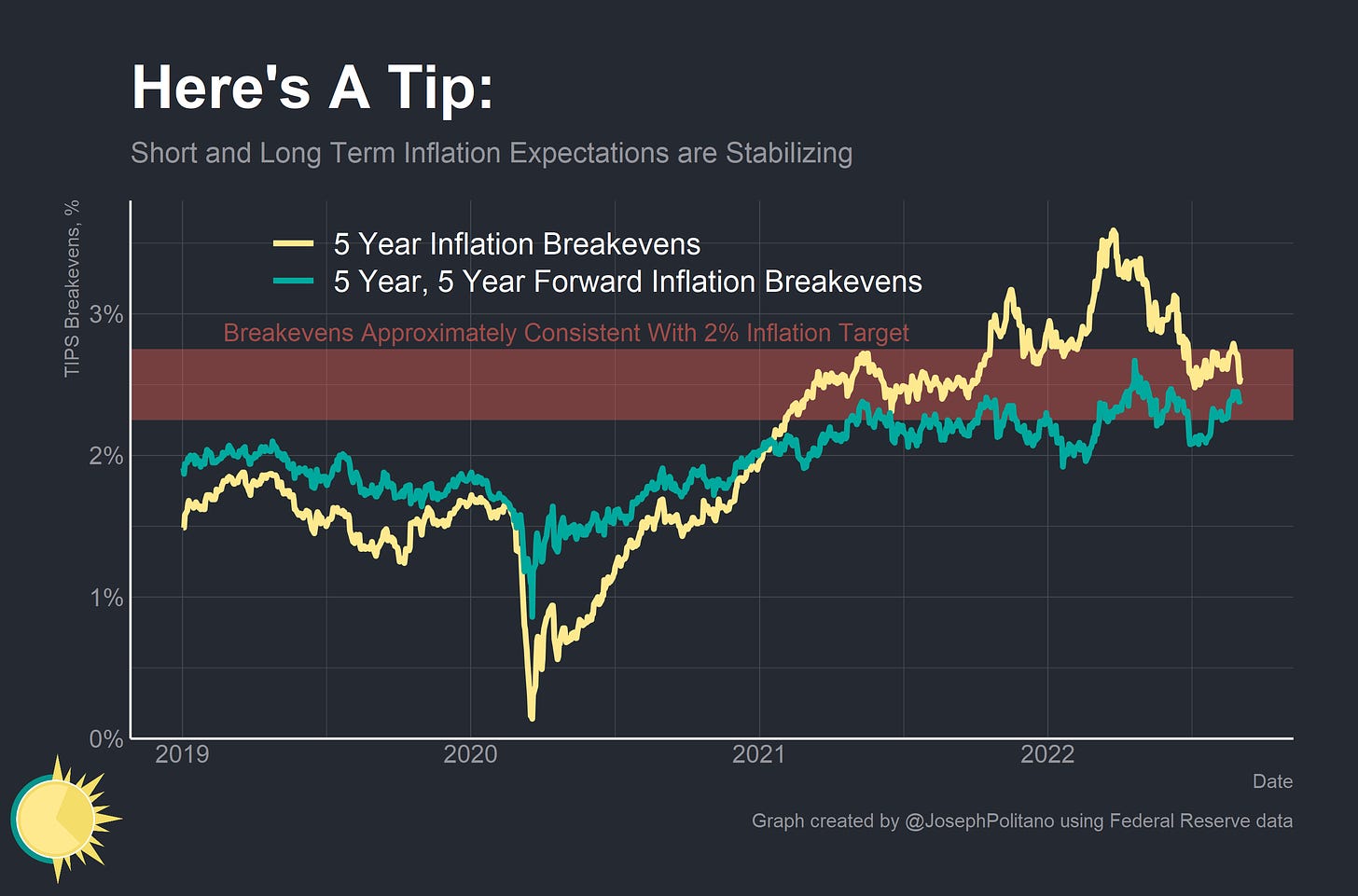

Market-based measures of inflation expectations, on the other hand, are partially problematic because they give one unified measure of aggregate forecasts that can conceal disagreement. TIPS breakevens are inflation expectations calculated from the difference in yields between inflation-indexed and normal, non-inflation-indexed treasury bonds. However, calling them inflation expectations is even a bit of a misnomer—they are inflation compensation, the price for accepting the risk associated with holding non-inflation-indexed bonds. This includes both inflation expectations, inflation uncertainty, and a volatile liquidity premium (especially early on, inflation-indexed bonds were relatively illiquid and therefore had higher yields).

TIPS breakevens are a relatively good inflation forecast though—after all, better forecasters can plausibly make lots of money through price discovery in TIPS markets—but the fact that they have to be adjusted so much to “reveal” true inflation expectations makes them an unreliable indicator. The best simple practice is usually to evaluate them based on a rough band approximately consistent with the Federal Reserve’s 2% inflation target—which would put breakevens between 2.25-2.75% once you account for illiquidity, inflation uncertainty, and the tendency for CPI (to which TIPS are indexed) to overshoot PCEPI (the inflation index that the Fed targets).

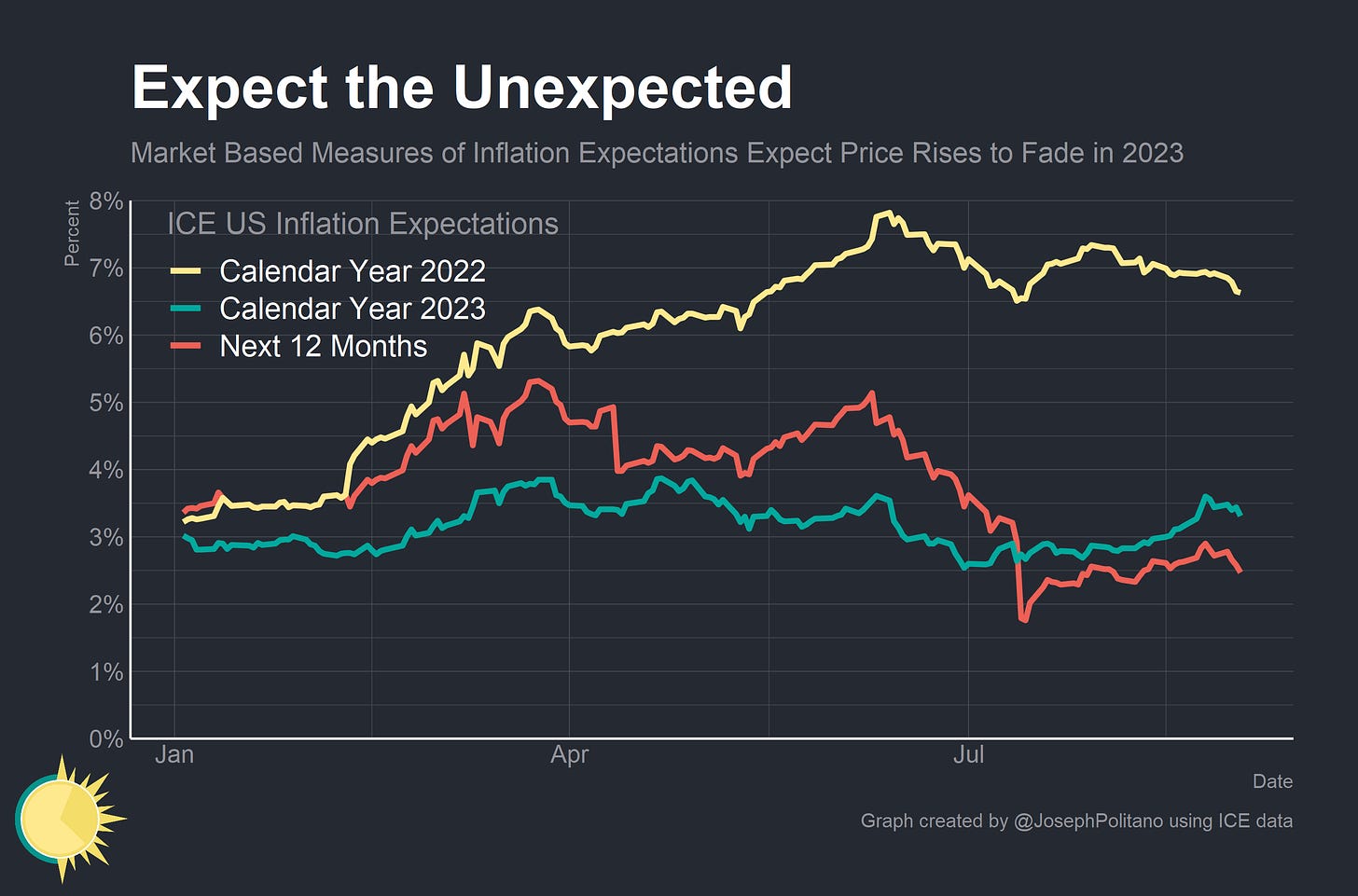

Over shorter time horizons inflation swaps, not TIPS, are the primary basis for measuring inflation compensation. However, these also have to be adjusted for inflation uncertainty, illiquidity, hedging behavior, and other risk factors to “reveal” true market-based inflation expectations. ICE has developed one such adjusted index, incorporating information from CPI swaps and TIPS breakevens to come up with measures for inflation expectations over various time intervals. Their measures’ forecasts have annual inflation holding near 7% by year-end before dropping down to 2.5-3% about a year from now. However, their forecasts from last year also expected inflation today to be 2.73%—so it’s worth taking even market-based forecasts with a grain of salt, though there may not be better alternatives.

Conclusions

What can we make of all this? For one, households’ and firms’ inflation expectations are not as well-anchored as most believed. Faced with rising prices, they have started paying much more attention to inflation and revising their expectations up quickly. But just as low inflation expectations did not prevent today’s bout of inflation, high inflation expectations need not prevent the disinflation needed to get inflation back on target.

However, there remain important causal mechanisms by which consumer and firm inflation expectations can manifest higher inflation. Well-formulated measures of firms’ unit cost expectations and consumers’ buying intentions can reveal information that is hidden in direct questions about inflation expectations. The fact that firm unit-cost inflation expectations remain highly elevated should be worrying, as is the idea that consumers are increasingly looking to make large purchases ahead of price hikes despite terrible buying sentiment. Following the actions, not just the intentions, of economic actors will be critical to monitoring inflation.

If there is any saving grace of rising inflation expectations it’s that more people are now paying attention to the actions of the Federal Reserve. Clear communication from them will therefore likely have a bigger impact than ever before. The public will likely need to be re-convinced though—talk is cheap, and faith without works is dead. Solving inflation expectations will, unfortunately, likely require solving inflation.

Very nice work. Three gold stars!

This is a superbly-written piece; crystal clear!