Universal Tariffs are Universally Bad

Trump's Plan for Aggressively High Universal Tariffs Would be Horrible for the US Economy

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 45,000 people who read Apricitas!

In his first term, Trump used his executive power to kick off a massive trade war with China while tearing up or renegotiating existing trade deals to significantly increase US protectionism. The Biden administration has maintained much of that trade-skeptical attitude, carrying over many of the trade restrictions first implemented by Trump while passing their own tariffs on EVs, batteries, steel, and more.

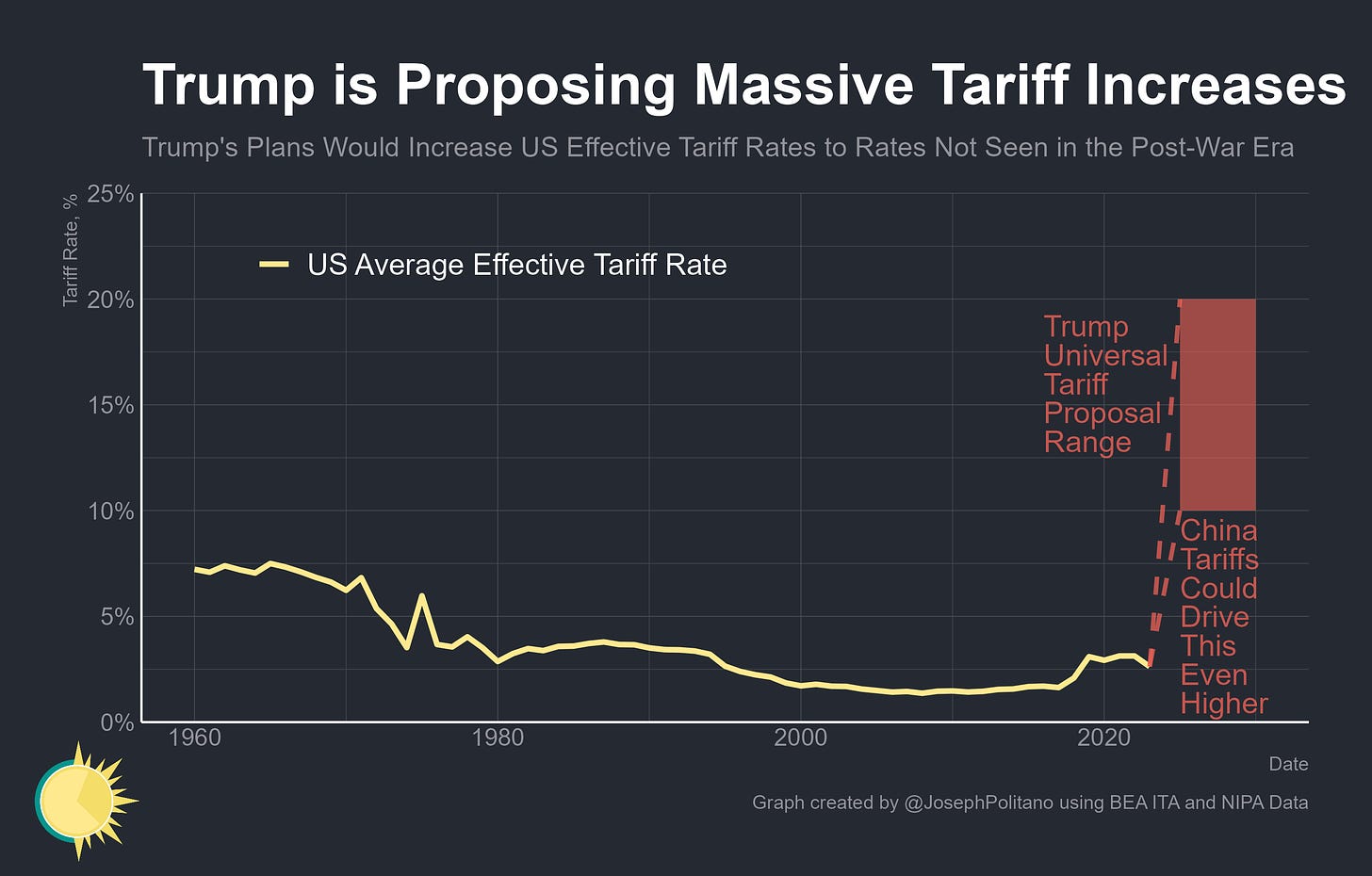

Yet for his second term, Trump is proposing further trade restrictions that make the near decade-long trade war look like a tempest in a teapot by comparison. His explicit plan calls for a universal tariff on all US imports (of between 10% and 20%) plus larger tariffs on Chinese imports (60% or more), and reciprocal tariffs on nations that tax US exports. Beyond these initial policies, continuous escalation of tariff rates is frequently an implicit or explicit policy goal and Trump often personally threatens other large tariffs on specific countries, industries, and companies. The entirety of the last eight years of trade wars have driven average effective US tariff rates—the amount of customs duties paid as a share of total imports—up from 1.6% in 2017 to 2.6% in 2023. Trump’s plans promise to at least quadruple that tax rate, and possibly increase it by 7 times its current levels or more. There is simply no modern precedent for US tariff rates anywhere close to that high.

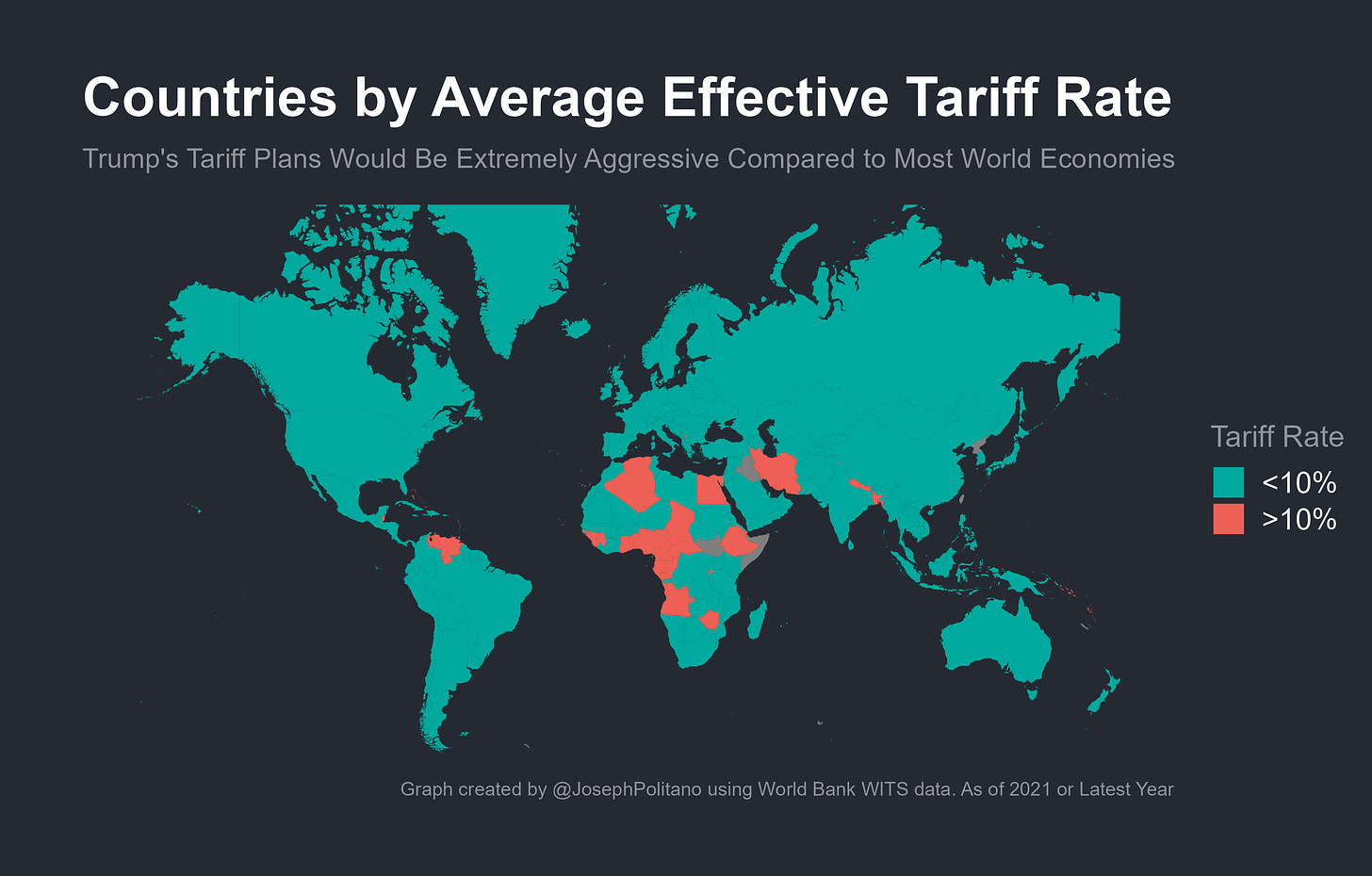

Moreover, Trump’s tariff plans would also be out of step with policy in all of the world’s prosperous high-income nations—most countries with effective tariff rates near the levels he is proposing are pariah oil producers or struggling low-income agricultural economies. No strong major global economy functions with tariffs that high because the consequences would simply be so overwhelmingly negative—the closest analog to the size and scope of Trump’s proposals are the infamous Smoot-Hawley tariffs that contributed to the Great Depression.

Universal tariffs as high as Trump is proposing will substantially increase prices—US consumers will bear the brunt of inefficient taxes on a wide variety of basic foods and essential goods that physically cannot be produced stateside, with the poorest households being hit the hardest. American industry will struggle amidst higher costs for key intermediate supplies, machinery, and equipment, dwarfing any marginal benefits from reduced foreign competition. Universal tariffs will primarily hit products bought from America’s closest allies, worsening the country’s geopolitical standing compared to China and completely isolating it from the international community. The inevitable retaliatory tariffs would crush large American exporters and begin an escalatory spiral with no clear off-ramp. As President, Trump would have broad unilateral authority to increase tariffs in a variety of ways, and there would be massive negative economic consequences if he implemented even a fraction of his stated trade plans.

Laundering Bad Ideas

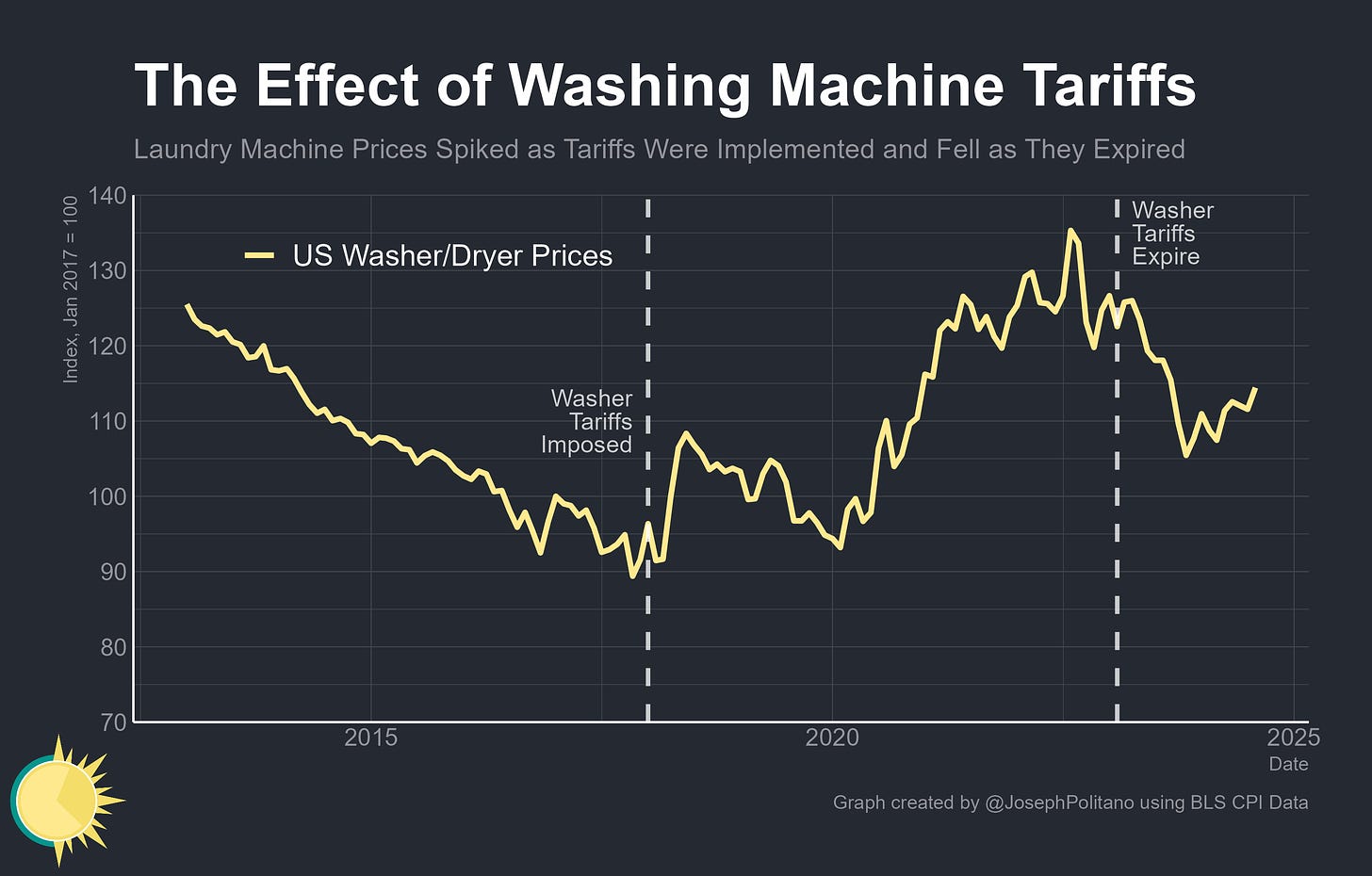

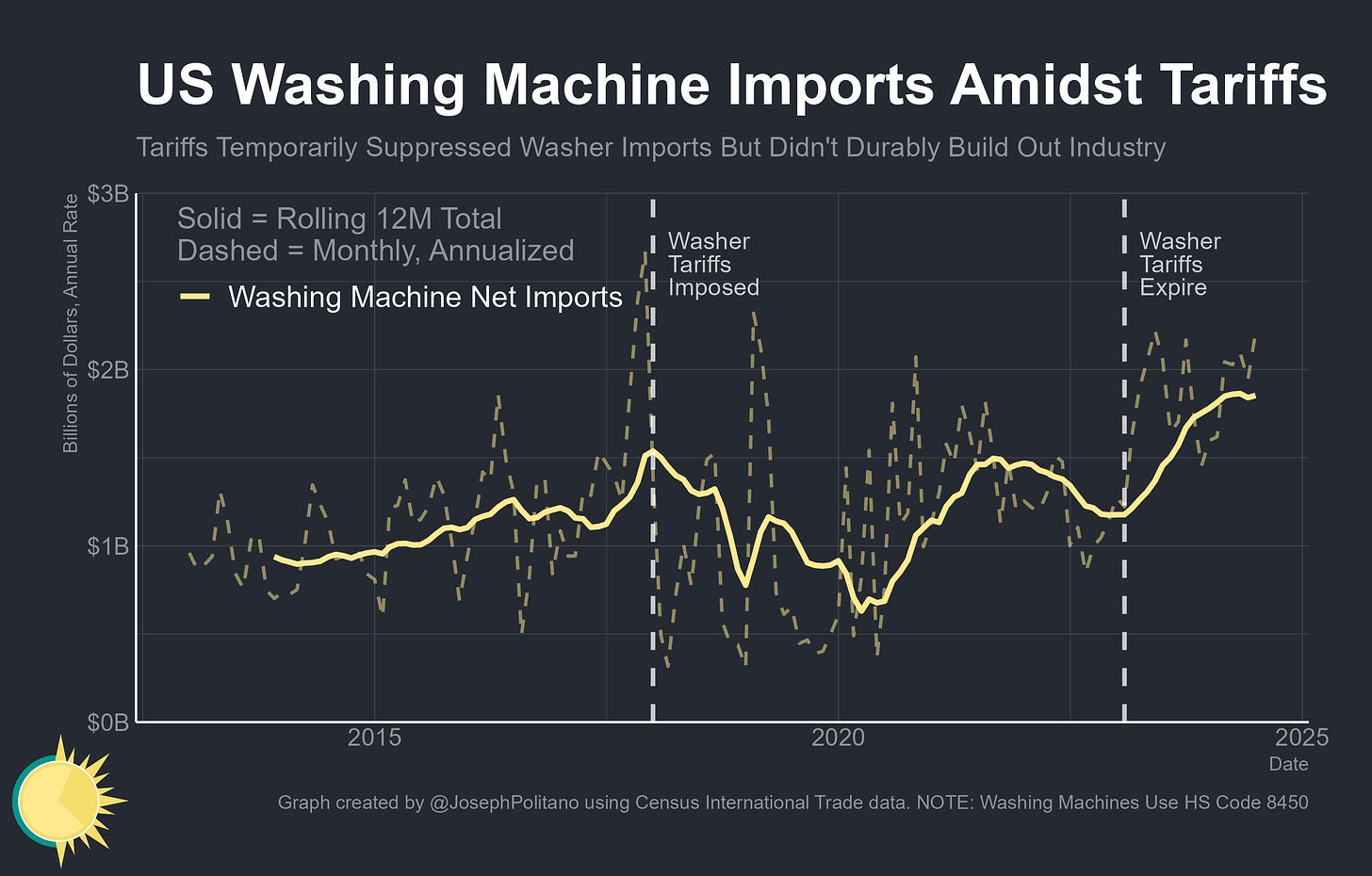

When asked to defend these aggressive tariff policies, Trump’s vice-presidential candidate JD Vance and other policy allies will point to the tariffs placed on washing machines back in 2018 as a successful example they’re attempting to replicate. The US washing machine market was already not operating under pure free trade, but the system implemented in 2018 was extremely aggressive even relative to the protectionist status quo—tariffs started at 20% and could reach nearly 50% depending on timing and market conditions. The explicit, written, intentional purpose of those tariffs was to increase the cost to consumers and stop the steady doldrum of price declines caused by foreign competitors—in official documents to Congress announcing the tariff, Trump said “this duty will provide an impetus for importers to increase their prices, thereby relieving the downward pressure on prices that has led to a decline in domestic washer producers' financial performance.”

By that metric, tariffs definitely achieved their goal—US laundry machine prices spiked significantly in the immediate aftermath of the tariff and remained high for years. However, in proponents’ retelling of the situation, that spike was only temporary and prices soon came back down as investments in American washer manufacturing successfully built out domestic capacity. By early 2020, they say, prices had fallen back to pre-tariff levels before the unforeseeable effects of the COVID pandemic shot them back up again.

Yet in actuality, prices remained high even years after the tariffs were implemented, especially when you consider that in their absence prices would have likely dropped another 5-10% as they had throughout the early part of the 2010s. Second, purchases of household appliances stagnated after years of growth, meaning the tariffs were strong enough to durably reduce the number of washers and dryers Americans bought relative to the counterfactual. Third, the tariffs were still binding even many years after their initial implementation—when the Biden administration let them expire in early 2023 laundry machine prices quickly declined, indicating that domestic industry wasn’t cost-competitive even after a full half-decade of protection from foreign competition.

Indeed, the vaunted domestic industry buildout was much weaker than tariff proponents would have you believe. US output and employment in household appliance manufacturing were stagnant for years after the tariff implementation, only really bouncing up after the COVID-era demand surge. As soon as the tariff was removed, imports surged and prices fell as competition increased and more efficient foreign firms were allowed to re-enter domestic markets.

The economics of this clearly did not shake out positively—consumers spent years paying higher prices for inferior products to support a domestic industry that remains no stronger or more efficient than it was a decade ago. Plus, washing machines are not a product like semiconductors where you can make a credible national security argument to justify overpaying to build out domestic industry. Nor was this a case of accepting an economic cost to decouple from geopolitical rivals like China or Russia—prior rounds of specific anti-dumping tariffs had already dramatically reduced US imports of Chinese washing machines, so the 2018 tariffs effectively hit imports from close US allies like South Korea alongside tariff-hopping manufacturers in places like Vietnam and Thailand. That universal tariff proponents see this outcome as a policy success is instructive and indicting.

Why Tariff Bananas?

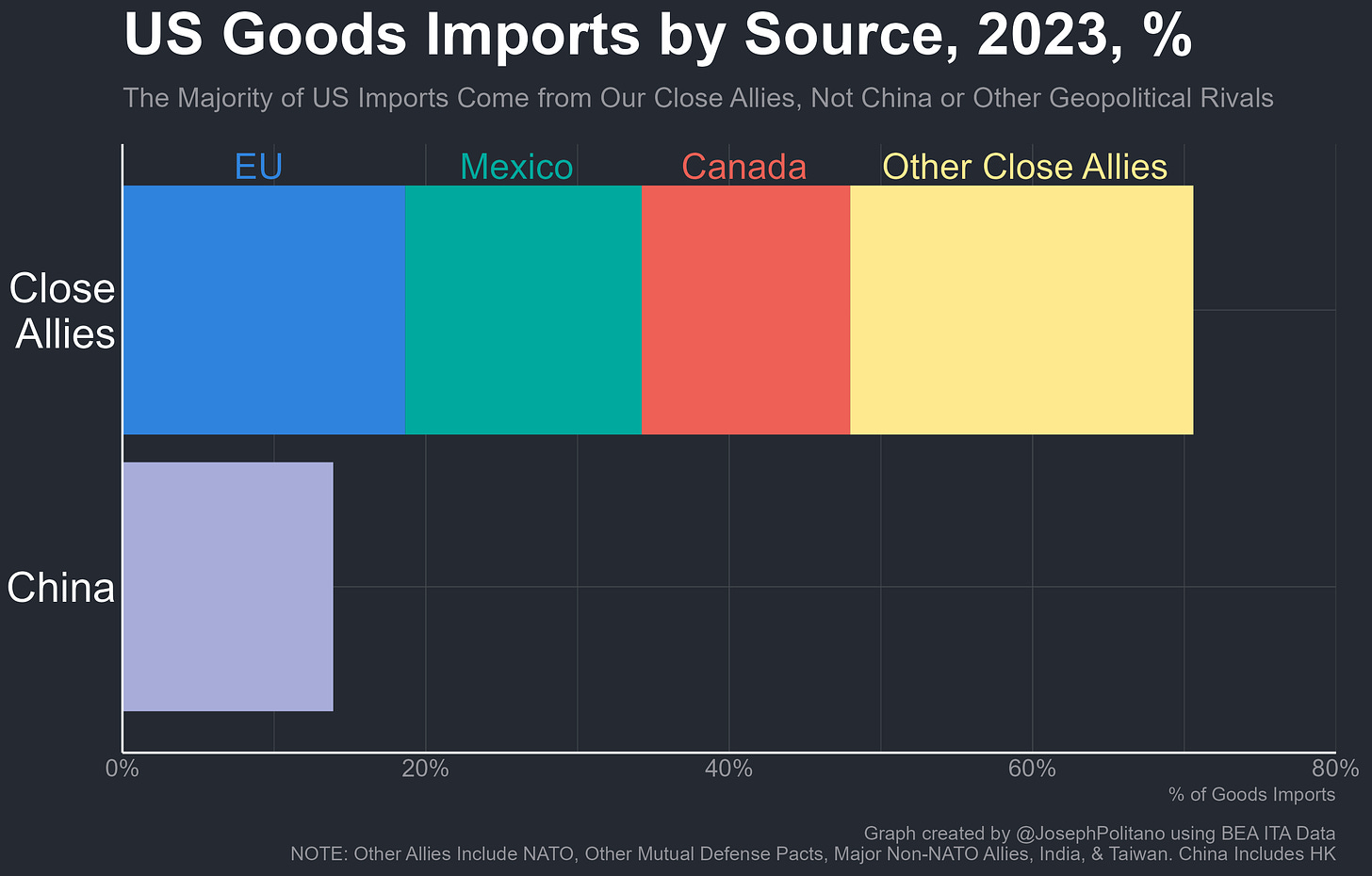

Even still, I regret beginning the discussion on their terms by even talking about washing machines—they want the argument to be about the relative cost-benefit of tariffs on the subset of consumer goods imported from China because you can sketch out stronger arguments for the industrial and geopolitical benefits of tariffs on those goods. The actual reality of a universal tariff is much, much, worse, instead primarily serving as a tax on many essential goods and obviously-beneficial trade relationships with our closest allies.

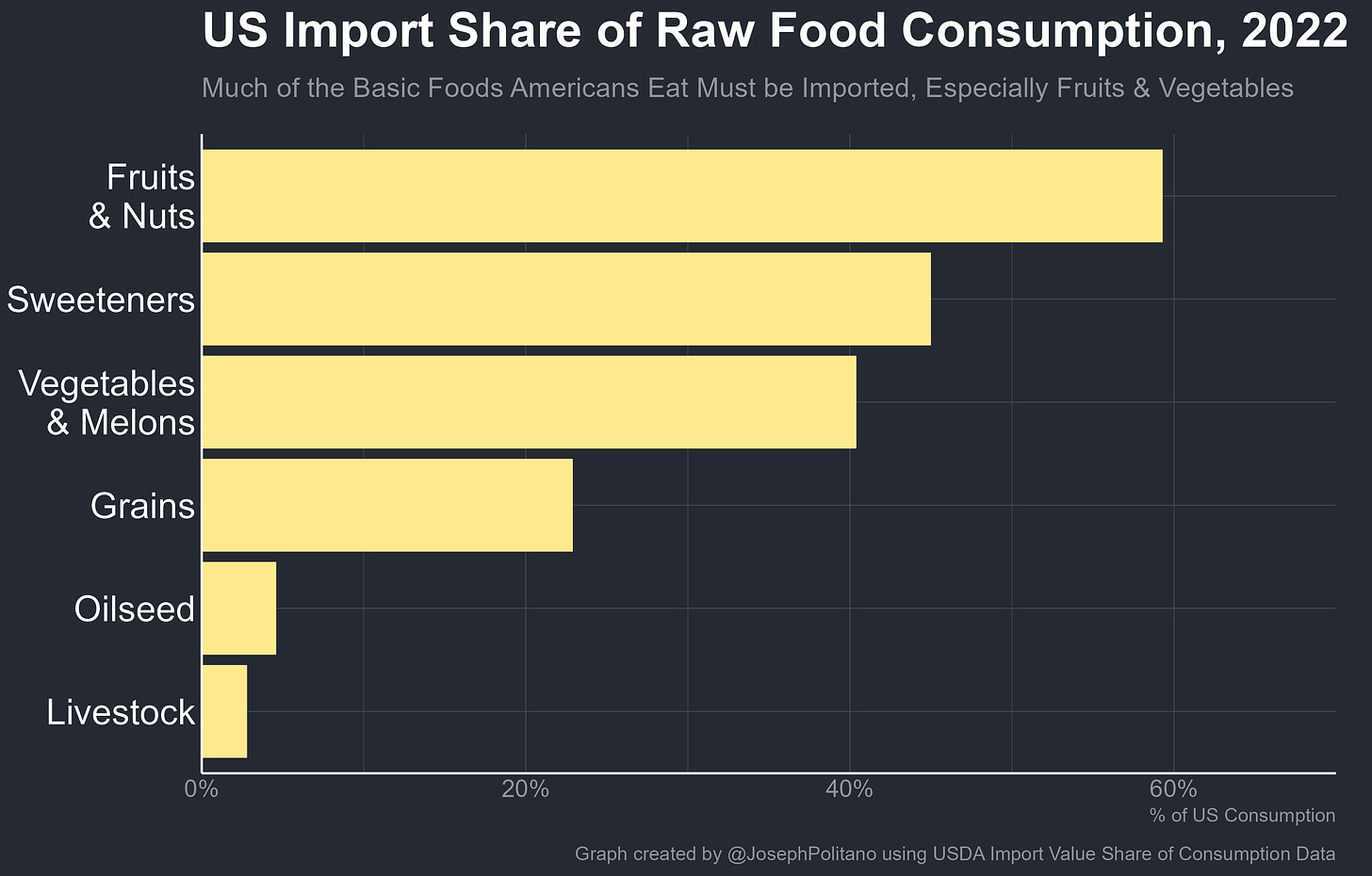

First, America imports a wide variety of items that simply cannot physically be produced in large enough quantities to satiate domestic demand. To use some illustrative examples, plenty of basic foodstuffs like coffee, bananas, avocados, cocoa, and much more do not grow in US climates, plus there are no domestic replacements for wild-caught Chilean Sea Bass or Yellowfish Tuna. These are not isolated edge cases—in 2022, imports made up nearly 60% of US fruit/nut consumption and 40% of US vegetable/melon consumption. In the coffee industry, all a 10%-20% universal tariff will achieve is reducing economic output by driving up the cost of coffee, enriching the owners of the few American plantations on the Hawaiian islands, raising revenue via obtuse regressive taxes, and enraging the couple-dozen US allies with major coffee industries.

The experts in Trump’s trade policy orbit know this, but instead of defending these policies, they deflect. Howard Lutnick, Trump’s transition chair, went on CNBC to defend the universal tariff plans and claimed Trump “understands ‘don’t tariff stuff we don’t make.’” “If we don’t make it”, he continued on, “and you want to buy it, I don’t want to put the price up. It’s pointless.” Of course, Trump’s universal tariff is explicitly premised on the idea of hitting every type of good no matter whether it can be made in the US or not. Oren Cass, the Chief Economist at American Compass and a contributor to Project 2025, wrote more than two thousand words in the Atlantic defending Trump’s universal tariffs by focusing almost entirely on manufactured consumer goods—he is tactically silent as to why imported Ghanaian cocoa and Mexican avocados must also be taxed. When pressed directly, Oren said “are there some things that we don’t really grow here—say, bananas—that you’re probably going to pay the tariff on? Yes” but he dismisses these as marginal, necessary casualties for the supposed benefits brought by tariffs on goods like washing machines.

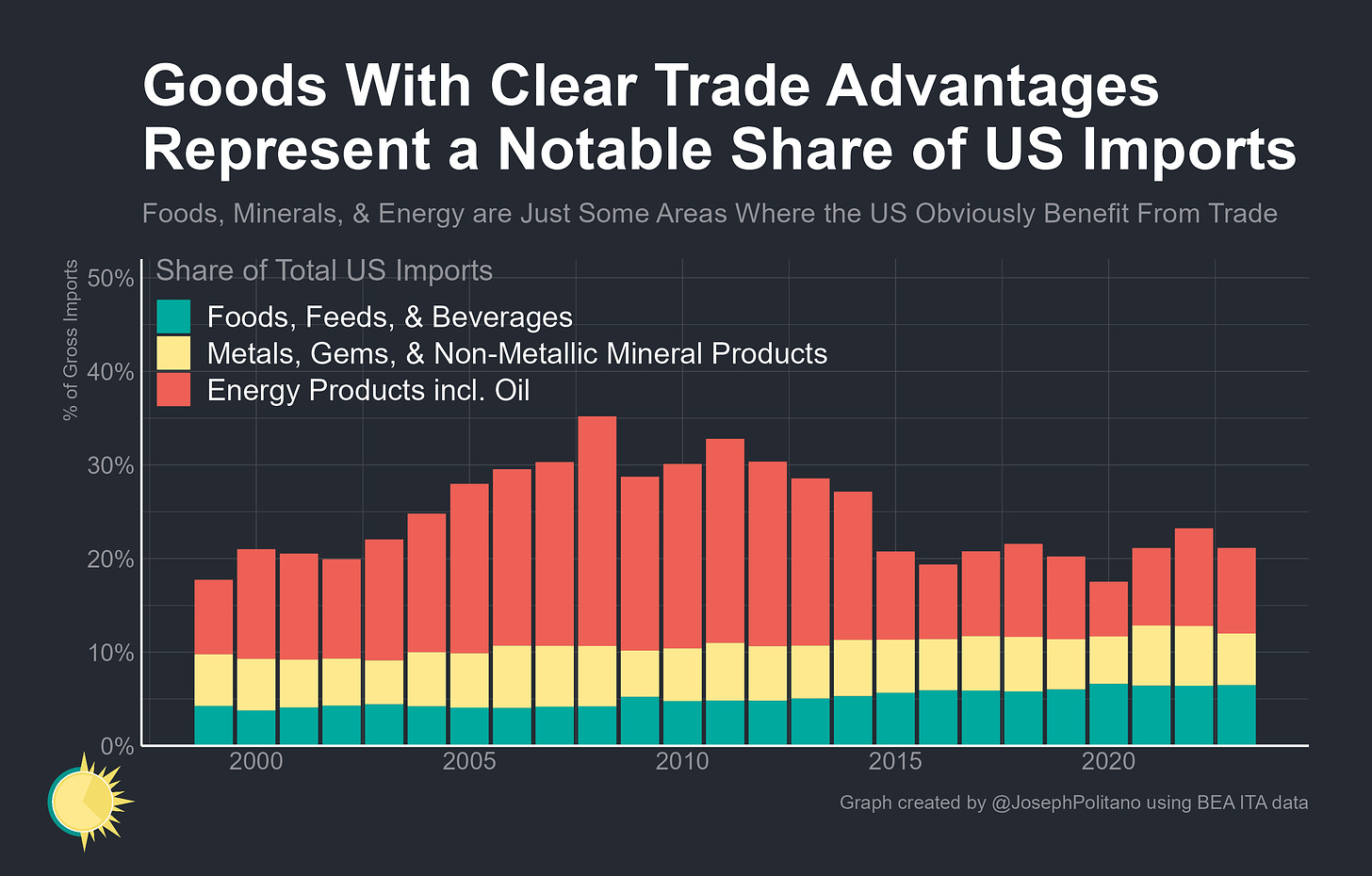

Yet these are not incidental trivialities in the grand scope of international trade—imports of fruits and vegetables were $50.7B last year, dwarfing total imports of all household and kitchen appliances by $12.8B. Including cocoa, coffee, and seafood that total jumps to $85B. Metal, stone, mineral, and gem imports were $171B in 2023, with many of those imports representing or deriving from key raw materials where insufficient deposits exist domestically. Universal tariffs would substantially raise the price of gasoline, especially in the Midwest, because America benefits significantly from easy access to Canadian crude oil and thus decades of infrastructure have already been built to transport and refine it. Purchases of oil and other foreign energy products were $252B last year, representing 8% of total US imports, of which half came from Canada. Universal tariffs would make it much pricier for Americans to get beloved Mexican tequila, French champagne, and Japanese sake—among thousands of other examples where the benefits of trade are patently obvious yet ignored.

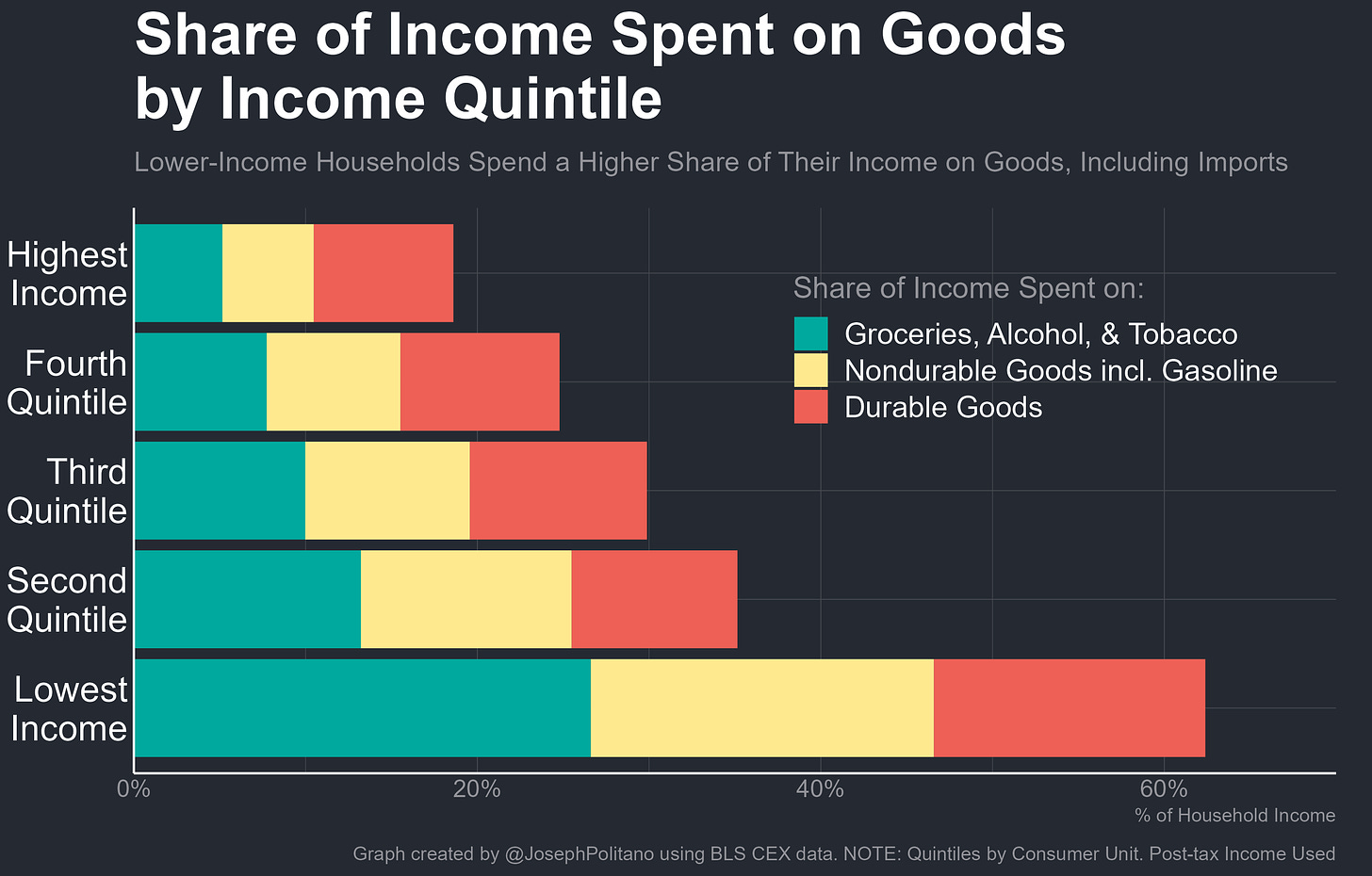

To consumers, a tariff on goods that can realistically only come from imports ends up as effectively a high and poorly structured sales tax. No state in the US imposes a sales tax rate of 10% even when you account for the average burden of local sales taxes, so the low end of Trump’s universal tariff proposals would be extremely high relative to current tax rates. It is also imposed on a random subset of items that happen to come from overseas, treating mangoes as if they are cancer-causing poisons like cigarettes where the government can justify high sales taxes to reduce social harms. Most importantly, the taxes only hit goods and exclude services—thus low-income Americans who spend a much higher share of their income on goods (including basic foodstuffs) would be hit the hardest by universal tariffs. These are not dismissable harms, yet universal tariff proponents handwave them away because they simply have no good justification for taxing bananas.

De-Industrial Policy

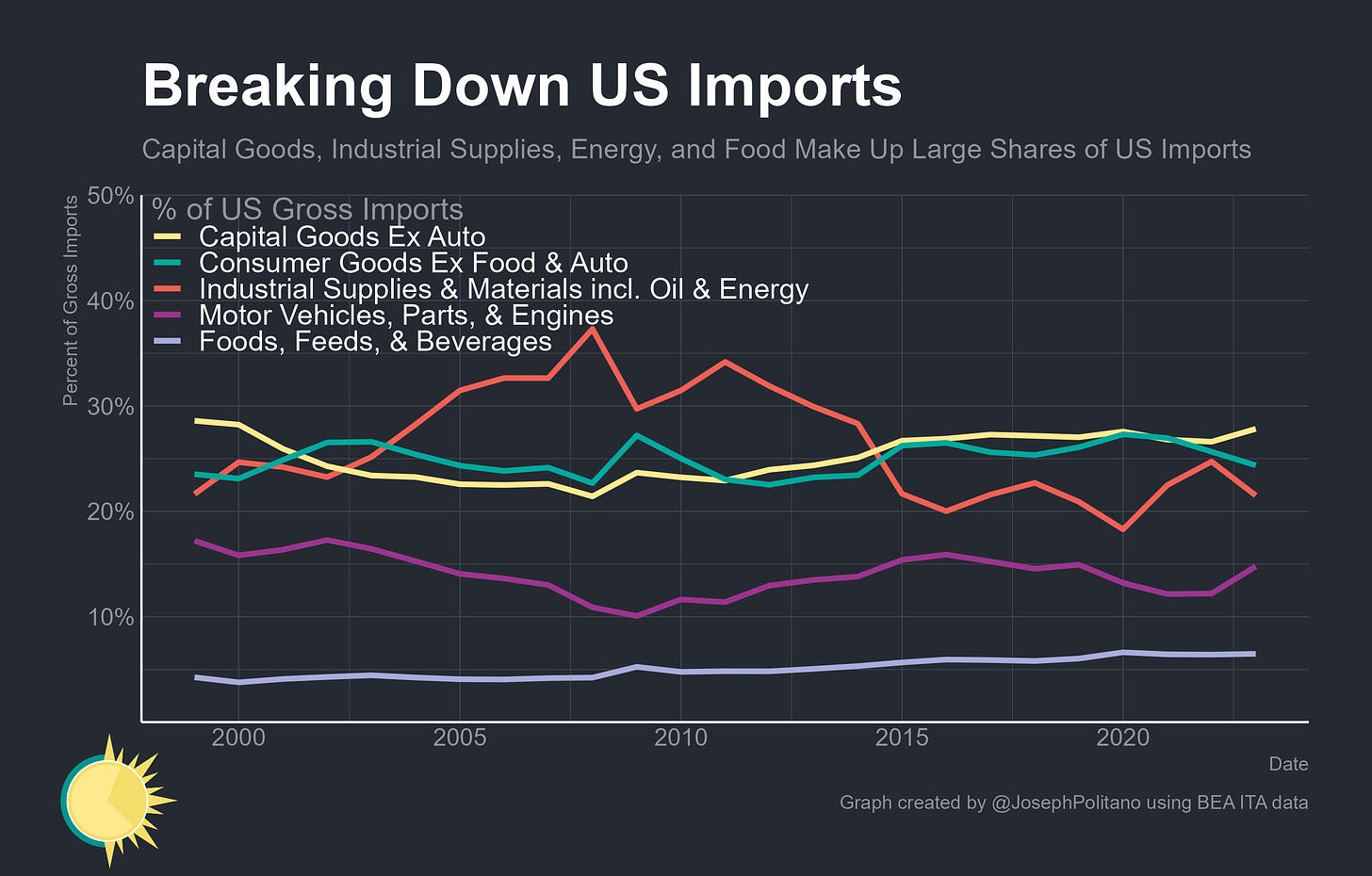

Universal tariffs raise prices by design, but more fundamentally they decrease economic output by acting as a tax on trade. Even for the industries that are supposed to benefit from protectionism, universal tariffs would end up having massive net negative impacts by driving up the costs of key imported raw materials and equipment. That represents an extremely large hit for American manufacturers, especially in today’s world of highly specialized global supply chains—equipment & capital goods represented 28% of US imports last year while industrial supplies & materials represented another 22%, and that’s before accounting for the massive trade in the motor vehicle supply chain.

Think about America’s ongoing semiconductor industry buildout as an example—in the wake of CHIPS Act subsidies, Intel has bought several high-end Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines from Dutch semiconductor equipment giant ASML and is importing them to the US to help boost American chip production. Each of these units has a cost that numbers in the hundreds of millions of dollars and there are currently no American alternatives available, so Intel would have to pay tens of millions more to reshore US chip production if universal tariffs were implemented. In reality, production would become more likely to move from Oregon to Ireland or other countries that did not place massive additional costs on necessary equipment. The cost of tariffs on imported washing machines may be borne primarily by consumers, but tariffs on imported lithography machines, construction equipment, steel, and much, much more would be borne primarily by American businesses and workers.

Moreover, the vast majority of American imports come from close economic and political partners rather than rivals like China. Last year, more than 70% of all goods imports came from the EU, Mexico, Canada, and other close American allies, with even more coming from countries with neutral-to-positive US relations. Trump and his trade circle claim that tariffs are primarily paid by foreigners to overwhelming contradictory evidence, but even if they were right their policies would primarily be hurting American allies. In reality, US manufacturers would suffer tremendously under universal tariffs—in many key areas like car manufacturing, decades of trade policy have molded North America into a unified market where one vehicle’s manufacturing process can cross the entire continent as it progresses from part manufacturing to final assembly. Rending those intricate links apart would have enormous costs, as imports of vehicle parts & accessories stood at $191B last year. Global value chains are increasingly complex, and attempting to decouple from them wholesale would impose increasingly large costs.

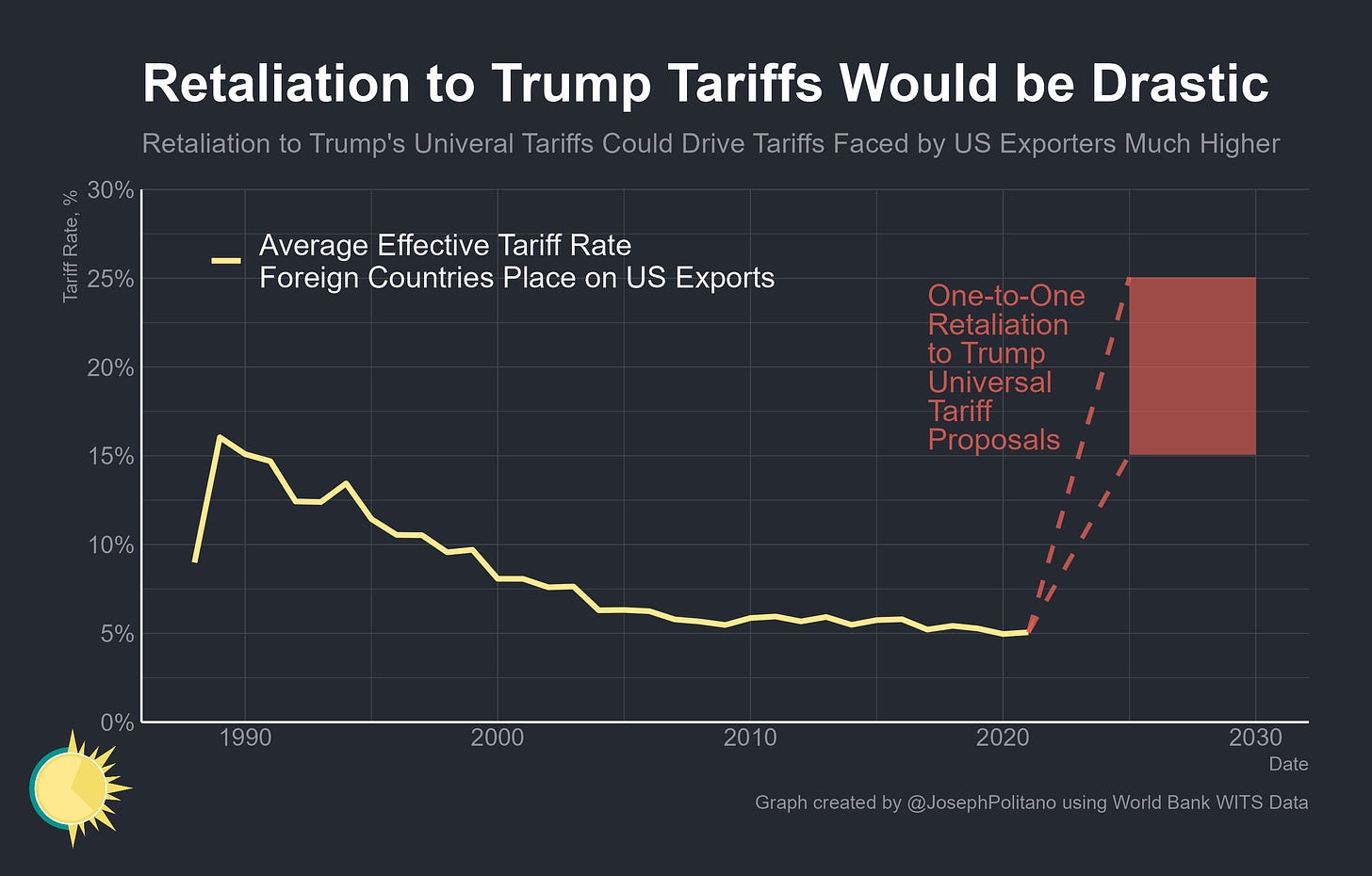

Finally, even if you think the costs of universal tariffs are borne by foreigners (specifically close US allies) and would benefit US industry (instead of harming it), the inevitably swift retaliatory tariffs and negative-sum global trade war would definitely harm America. Having the planet’s largest economy institute tariffs on every other country at the same exact time has the great disadvantage of unifying the world against the US, and even one-to-one retaliation would bring the effective tariff rate on US exports to the highest levels in decades. Plus, unlike retaliatory tariffs from the first China trade war, there would be nowhere for US exports to be rerouted to—in effect, the losses from reduced trade would be concentrated in the US on one side and split between the entire rest of the world on the other. In their marginally more sophisticated arguments, universal tariff proponents talk about the policy as giving the US a strong bargaining position to force other countries to reduce tariffs on American exports—in reality, it would do the exact opposite, sharply curtailing foreign market access for US businesses and undoing decades of work in negotiating free-trade deals.

To the extent it is possible, successful administration of basic industrial policy interventions requires policymakers to answer difficult questions. Is this specific sector worth bringing back to America? What combination of tariffs, subsidies, and loans are necessary to kick-start investment in the US? Will we accept inefficient domestic redundancies for national security purposes or are we aiming for an internationally competitive industry that will become a driver of growth? What parts of the necessary equipment and materials supply chains do we want to onshore and what are we okay importing?

This current administration at least has some answers—heavy subsidies coupled with targeted, aggressive tariffs on key industries like semiconductors, EVs, solar panels, steel, and critical minerals as part of efforts to build out those sectors domestically in the US. These types of policies have not proven historically successful in the US, they evidently failed in the individual case of washing machines, and I remain extremely worried they will fail again in the other industries they’re currently being applied to, but there’s at least a theoretical underlying economic logic—some low and middle-income countries have successfully used targeted tariffs in conjunction with other developmental industrial policies to kick-start key domestic manufacturing industries, maybe we can too.

Trump’s manufacturing plans don’t have any answers—there is no strategy beyond the tariff, and the tariff itself is treated as a strategy. This is an actively counterproductive way to even attempt to run industrial policy.

Conclusions

The most unintentionally revealing statements from people in Trump’s policy orbit are when they talk metaphorically about the supposed “negative externalities” of trade itself. Proponents of these universal tariffs do not see trade as an engine of economic prosperity that can be harnessed for good. Rather, they see it as an ugly byproduct of necessary production processes—factory sludge, dumped into a pristine river, that governments ought to strictly curtail.

That kind of sharp antipathy to trade is one of Trump’s most consistent policy positions, and nearly all of the administrative officials who constrained the worst impulses of his 1st-term trade policy will not be returning if he is reelected. As president, Trump would have broad unilateral authority to raise taxes on a wide variety of importeds, and even if he chose to pursue a smaller version of the universal tariffs he is currently proposing the costs to everyday Americans would be immense.

Agree with you Joseph. I don't know who needs to hear this, but if there is one consistent thread with the so called MAGA movement, it's boils down to this:

“Domestic”=Good

“Foreign”=Bad

There is no policy prescription other than to blame everything “bad” on outsiders (even if those outsiders are, in fact, domestic.) Pure ideologically driven nonsense that seeks to turn the US against the very cosmopolitan world that it helped build.

I find is incredibly worrying that many, otherwise intelligent individuals are buying into this simple, but false, narrative.

You are 100% correct. I think his tariff proposal is Trump’s worst policy stand. If he wins, I hope that it all quietly disappears (like most other Presidential campaign promises).