US Supply Chains are Recovering

After a Years-long Supply-Chain Crisis, Relief is Finally Here—Especially in Key Sectors like Semiconductors and Motor Vehicles

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 29,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

The early pandemic was dominated by acute supply-chain issues—hitting supplies of masks and PPE, then food and household essentials, then electronics and household durables, and finally spreading to virtually all consumer products. Americans were buying more goods than ever before while weakened global manufacturing hubs and congested international trade networks struggled to keep up the pace. A shortage of semiconductors and other electronic components wrecked complex manufacturing, especially the global car industry, while broad production constraints reached a fever pitch coinciding with the energy shortages of early 2022.

That supply-chain crisis put massive upward pressure on goods inflation—the price of manufactured goods in the US has risen 16% since the start of COVID, more than during the entire period from 1990 to 2020, with key durable goods like motor vehicles rising in price even more. Industrial output, GDP, and labor productivity were all hurt as producers struggled to source key inputs and keep their factories running.

Now, however, the worst of the supply-chain crisis is definitely behind us. Manufacturing output in key industries has recovered to pre-pandemic levels, materials shortages are abating, and international trade networks are normalizing. More than that, real goods consumption in the US has been stagnant for two years now, allowing time for manufacturing output to catch up—and actually driving a broad-based domestic industrial slowdown.

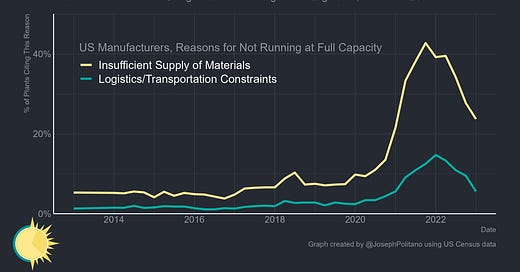

Cooling Capacity Constraints

The share of firms citing materials shortages or logistics constraints as a reason for running below full capacity has declined significantly according to recently-released data from the US Census Bureau. The share with a critically insufficient supply of materials has declined from a peak of 43% in Q4 2021 to 24% in Q1 of this year, while the share with logistics and transportation bottlenecks fell from 12.5% to 6% over the same time period. While both of these metrics would represent crises by pre-pandemic standards, they are nonetheless massive improvements compared to the state of supply chains just one year ago.

In addition, lead times for production materials—the time between order and delivery and a key shortage indicator—have shrunk significantly from early 2022 highs. On average, input lead times are hovering near 85 days compared to a peak of 100 days and a pre-pandemic average of roughly 70 days. Prices for a wide range of early-stage production inputs have likewise declined over the last year, the first such deflationary impulse since early 2021, and a further sign that input shortages are alleviating.

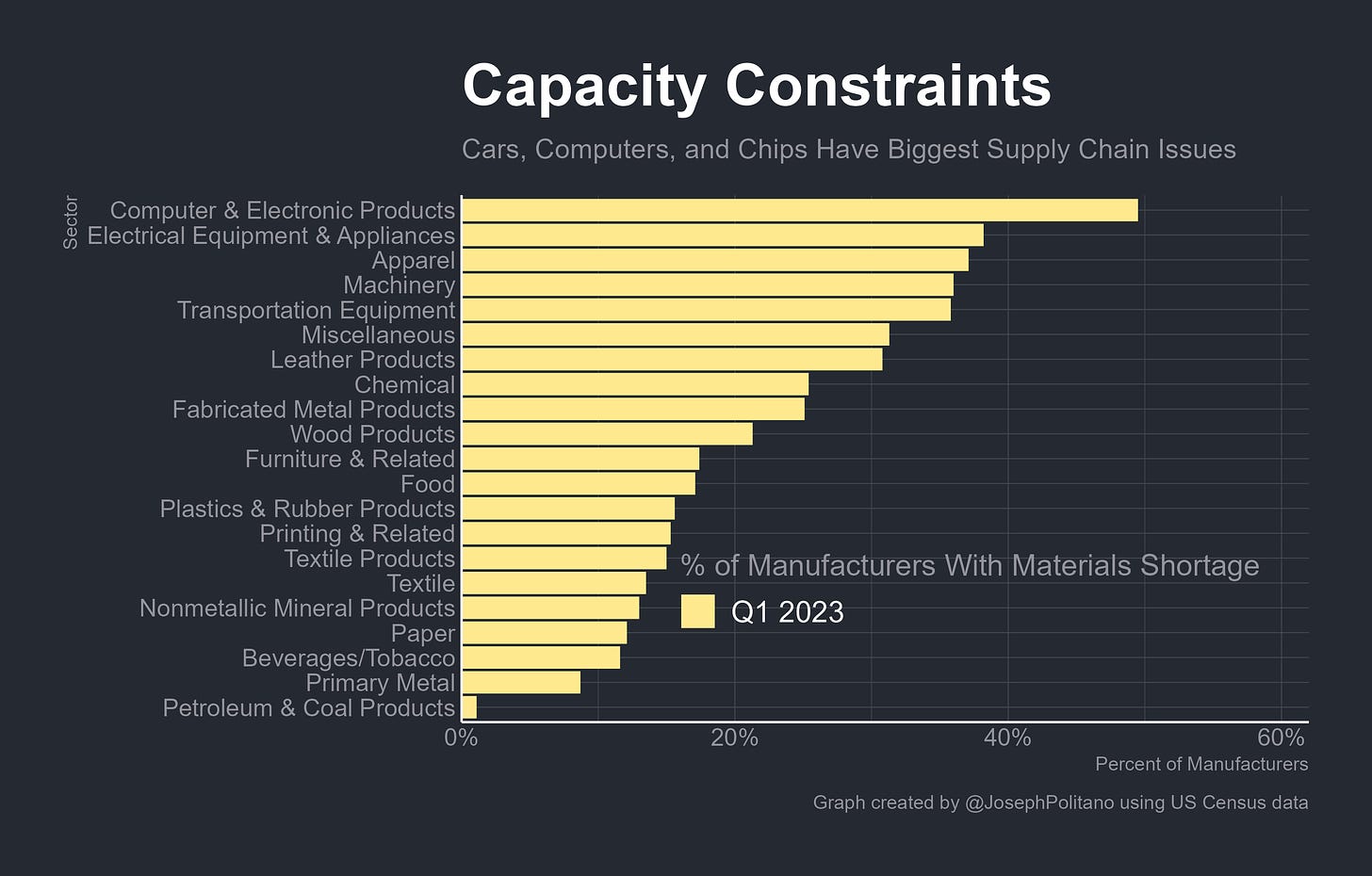

However, supply constraints remain disproportionately concentrated among high-complexity electronics and durable goods manufacturing industries even as they ease. The share of computer/electronics manufacturers citing materials shortages as a constraint on output remains near 50%, while equivalent numbers for electrical equipment, machinery, and transportation equipment (mostly car) manufacturers remain above 35%—among the highest for major industries.

Indeed, there are only four input commodities that remain in short supply according to US manufacturers—down from more than 35 at the peak in mid-2021. Plus, three of the four inputs—semiconductors, electronic components, and electrical components—have been continuously in short supply for two and a half years at this point, indicating just how long acute supply shortages can persist.

However, it is now clear that the worst of the semiconductor shortage is over, with the share of US computer and electronics manufacturers citing materials shortages falling to the lowest levels since mid-2021. Likewise, the share of transportation equipment manufacturers citing materials shortages as a production constraint has fallen to the lowest level in two years.

More frequent and up-to-date data on US car production shows a near-complete recovery—total motor vehicle assemblies reached the highest levels since mid-2020 last month, with light truck assemblies notching a new all-time record high. That corroborates data on the easing of the chip shortage we’re seeing across the globe—European car output hit the highest level since 2020 in February, Japanese car output is at the highest level since 2021, and Mexican car output is at a record high. Those supply improvements should hopefully continue passing through as lower prices, especially in the used car market where wholesale data suggests prices have fallen 3.2% in the first half of June.

The End of the Goods Demand Boom?

The initial US supply chain crisis has to partially be understood as a crisis of abundance—it was not simply that COVID impaired production abilities and logistics networks, but also that Americans were consuming significantly more goods than could reasonably have been expected by producers before the pandemic. By early 2021, US real durable goods consumption had jumped 20% above pre-pandemic levels, condensing roughly 4 years of normal growth into just 12 months. Globally, this was highly unusual, with the increase in US goods consumption making up the vast, vast majority of the total rise across the OECD, and holding well above pre-pandemic levels even years throughout 2021 and 2022 thanks to America’s heavily stimulative positive mix and rising spending power among lower-income households that put more of their consumption towards goods. Yet we are now in 2023, and the boom in goods spending has slowed down considerably, with real consumption being mostly flat for two years straight and essentially back in line with the pre-pandemic trend.

The waning of consumer spending amidst the easing of supply constraints has left domestic manufacturers increasingly more demand-constrained than supply-constrained. The share of plants citing insufficient orders—usually the dominant reason for running below full capacity—as a constraint on production has risen for three straight quarters and now sits at the highest level since early 2021. It’s also worth noting that labor constraints have remained more binding than materials constraints even as they ease, indicating how relatively tight the job market remains.

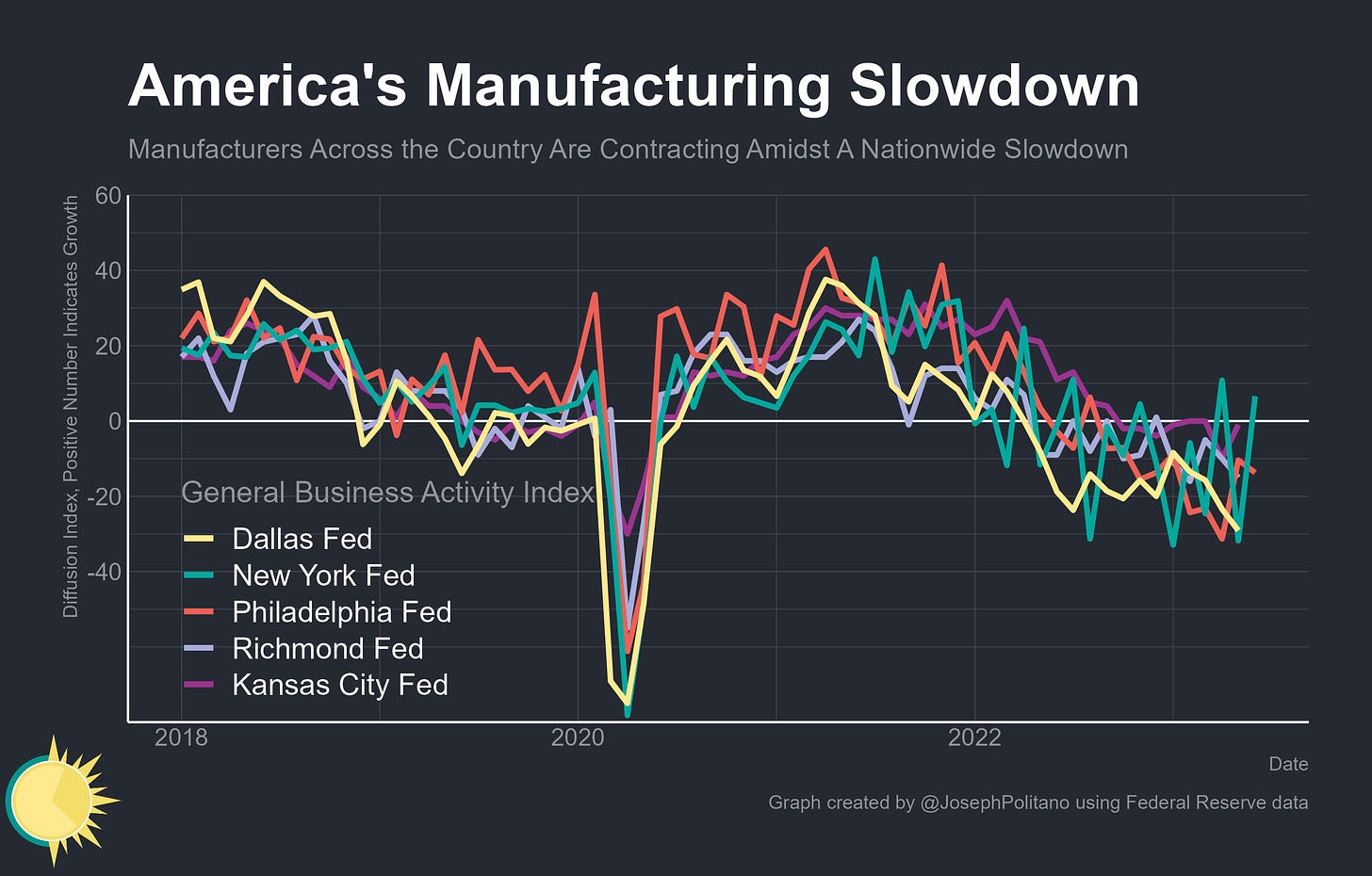

Plus, that weaker demand has also led to an ongoing slowdown in US manufacturing output—essentially all of the regional Fed manufacturing activity diffusion indices have remained decidedly negative for the bulk of the last twelve months, indicating an ongoing contraction in output. Headline manufacturing production is still down 0.3% over the last year despite a 10% jump in the output of motor vehicles and parts. There are some signs that manufacturers are getting more optimistic about a future rebound, and the recent recovery in volatile New York Fed data is a good sign, but the dominant recent industrial dynamic has been one of slow contraction.

Conclusions

The buildup of US manufacturing capacity in the wake of the CHIPS Act and Inflation Reduction Act is also continuing at a record pace—domestic construction spending reached an annualized rate of nearly $190B last month, more than 50% of which is going to computer and electronic manufacturing facilities like semiconductor fabricators. There has also been a notable boom in transportation equipment manufacturing construction as carmakers start building out US electric vehicle supply chains and responding to incentives from the IRA. In other words, large capacity increases are in the pipeline for the industries that were most affected by recent supply-chain issues.

The underlying motive for subsidizing those domestic manufacturing investments was to counter inflation by building out aggregate supply to meet elevated demand. At the moment, it looks like much of that capacity will arrive too late to make a significant difference for current supply chain troubles—in upstream inputs like semiconductors, demand has already cooled to such a degree that output has contracted in many foreign production centers. Yet the US has pursued a similar path as many countries in the wake of the pandemic-era supply chain crisis—investing large sums in capacity, hoping to build resilience and strength in supply chains as a buffer against possible future crises.

It's quite unbelievable that supply chains still haven't recovered and are not even that close to full recovery. The size of the COVID shock has simply been significantly underappreciated. And these supply chain issues are in real terms (not just higher prices and can't be quickly fixed) - like delivery delays or lead times. I thought supply chain issues would have dissipated by now.

As long as the real costs remain higher than pre-pandemic levels, the inflation rate will remain elevated, as the inflation rate depends on the level of real marginal costs. That's what the Economic models of central banks tell us:

https://www.nominalnews.com/p/unintuitive-inflation-supply-wages