Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 8,300 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

Americans are increasingly worried about a recession. Consumer confidence is shaky, business executives are antsy, and political leaders are stressed. Technical indicators like employment and real income growth remain positive if weaker, but the American public has soured on the economy amidst increasing anxiety about inflation. We are in the midst of an undeniable vibecession—people are mad about the state of the economy and are pessimistic about its future regardless of what professional economists or payroll employment numbers have to say.

And amidst this background the risks of a recession truly have been increasing over the last few months. Aggressive monetary tightening from the Federal Reserve is worsening financial conditions, a global energy crisis has worsened supply side pressures on the economy, and slowdowns in Europe and East Asia are causing negative spillovers in America. A recession is by no means guaranteed—my personal reading of the tea leaves is that financial markets are pricing in a slowdown that would be worse than 2018 but not quite as bad as 2016, neither of which were recessions—but it remains a critical risk to monitor.

With that, how can we track recession risk as it evolves? What are good datapoints to track—and pitfalls to avoid. And how can we measure the severity of a recession, if or when one happens?

Know Thyself

“How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked.

“Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually and then suddenly.”Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises

Recessions are notoriously hard to predict—and economists are notoriously bad at predicting them. For one, a predictable recession is usually an avoidable recession, and an avoidable recession is usually one that never happens. For two, even with the rapid advances in real-time economic data analysis over the past decade it still remains hard to get a live, accurate, complete pulse on the state of the economy. Data like payrolls, Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and retail sales are all revised after publication and can therefore lag the “live” state of the economy by several months. All data has flaws, and a lot of data’s flaws have been exacerbated by the pandemic and the unprecedented economic situation we find ourselves in. Finally, most recessions usually start out as minor slowdowns that subsequently rapidly worsen. Separating the slowdowns that will get better—like 2016—with the slowdowns that will rapidly get worse—like 2001—beforehand is extremely difficult.

Let’s start by looking at corporate bond spreads, which have now surpassed their 2019 highs as financial conditions continue tightening. Worsening financial conditions are both a goal of the Federal Reserve’s efforts to contain inflation and an approximation of the recession risk facing firms. If tighter monetary policy is constricting demand and elevating recession risks, firms will be less likely to successfully repay loans in the future and will therefore find it more difficult to borrow today. Here’s where it is worth keeping financial conditions in perspective—right now high yield spreads remain below the levels achieved at the height of the Euro crisis in 2012 and the economic slowdown of 2016. Neither of those events caused a full blown recession in the US, and current pricing likely reflects a better financial outlook than during those recent slowdowns.

The other financial indicator to watch out for is yield curve inversions, when yields on longer-maturity securities go below yields on shorter-maturity securities. Investors have to price in significant rate cuts for the yield curve to invert, and that generally indicates a worsening economic outlook among market participants. Yield curve inversions aren’t perfect indicators—though they have preceded every recession in the US (the red bars in the chart above) their track record abroad is more mixed. The curve can also un-invert before a recession as it did in 2008 or 2018 (and the 2018 inversion obviously did not forecast COVID). Today’s high inflation environment could also mean that priced-in rate cuts simply represent real rates staying grounded while inflation falls instead of a recession call by market participants. Still, the shape of the yield curve remains another important indicator to watch in judging market participants’ fears of a recession.

Nothing To Excess

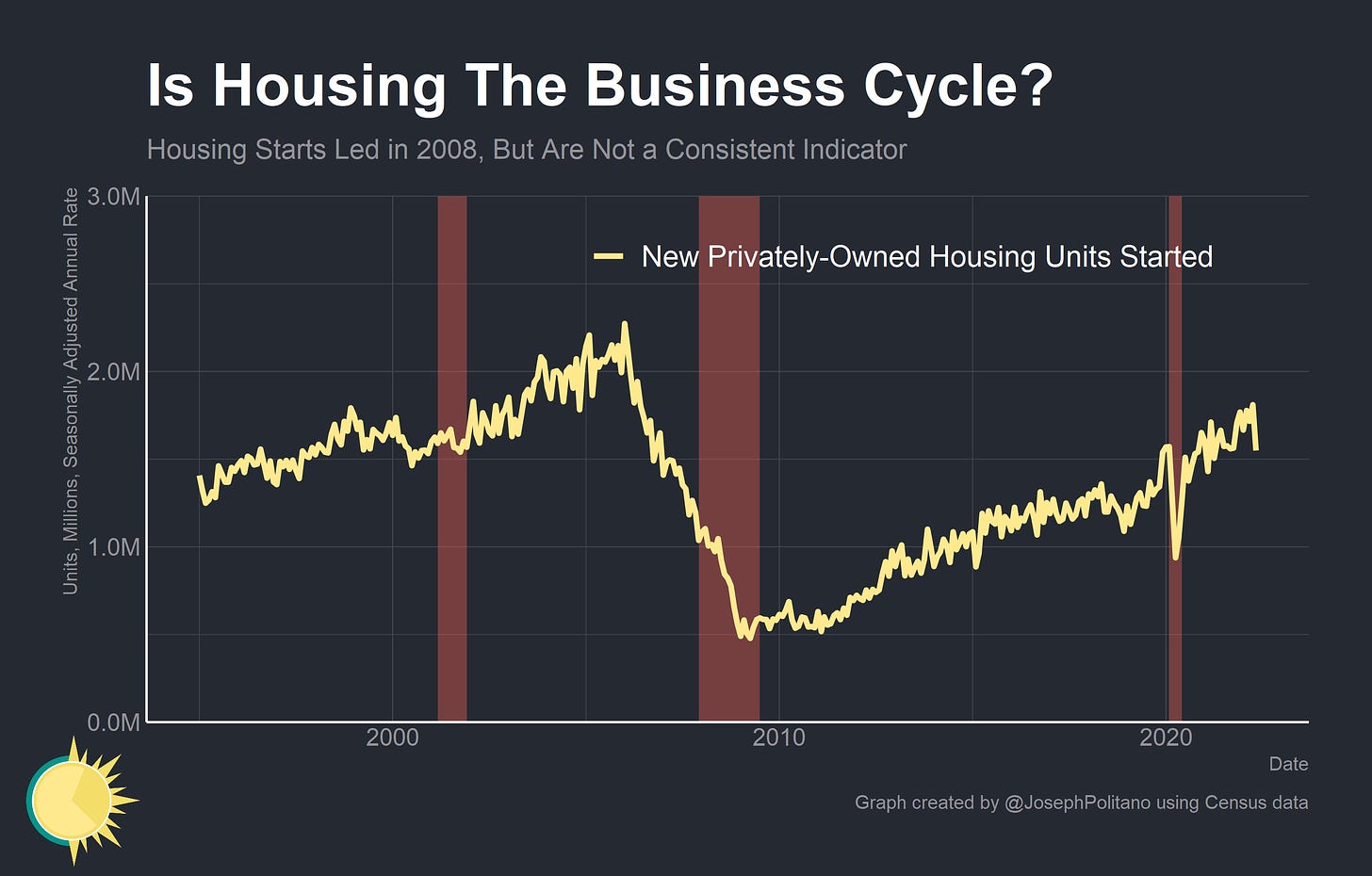

“Housing is the business cycle” is a common truism that, while slightly overstated, underscores the importance of residential investment as a driver of underlying economic growth, a direct channel through which monetary policy affects output, and a representative indicator of the state of households’ economic health. In fact, housing has possibly gotten more attached to business cycle fluctuations recently—construction is more concentrated in locations with permissive zoning and construction laws, meaning that labor markets and household balance sheets have to be strong enough to justify large amounts of internal migration in order to engender further increases in housing output.

We’ve already started to see the effects of higher mortgage rates on residential construction—housing starts declined 14% and permits declined 7% in May while employment in nondepository credit intermediation (which includes mortgage lending) and residential construction dropped in June. Further drops could indicate a situation where households are less confident about their finances and where a weaker labor market causes residential investment to decline.

Heavy weight truck sales are another possible “leading indicator” due to their relationship to domestic goods transportation demand. Since trucks are among the most common methods of transportation for domestic goods, perceived deterioration in goods demand will cause businesses to forestall truck purchases. This indicator, though might be muddled by the unique consumption patterns of the pandemic. Consumers have been spending a larger share of their income on goods instead of services since the start of the pandemic—a rebalancing towards further services spending would likely be an integral part of getting inflation down. Ongoing issues in the production of motor vehicles have left heavy truck output well below 2019 levels, so constricted supply could mix with pent-up demand in ways that obfuscate trucks’ signal as a recession indicator. Similar issues pertain to a lot of data on goods production—elevated pandemic goods consumption coming down to “normal” levels would be a positive for inflation, and alleviation of supply constraints in select critical sectors could lead to a boost of sales unrelated to macroeconomic conditions—both of which would obfuscate how the data relates to a possible recession.

Aggregate GDP data has been a flawed indicator of macroeconomic conditions so far this year as well. Rapid fluctuation in trade patterns and business inventories have affected previous headline GDP releases, and there is a widening gap in official statistics that is hard to explain. Gross Domestic Income (GDI) is supposed to be equivalent to GDP—the sum of all incomes in the economy should be equal to the sum of all spending since one person’s spending is another’s income—but the discrepancy between the two is rising significantly. We’ve seen this before on a smaller scale in 2007—GDI caught a weakening economy while GDP still suggested reasonable growth until 2008. Except now we have the reverse—GDP is suggesting a significant slowdown even as GDI growth is robust. Time will tell which had the better forecasting power, but for the time being keeping them both in view will be critical.

Certainty Brings Insanity

Still, recessions are fundamentally about unemployment—the “stag” in “stagflation” came from the stubbornly high unemployment rate paired with high inflation and the official arbiters of US recessions put the most weight on payroll and real income growth. The problem is that unemployment remains a bit of a lagging indicator—by the time workers are losing their jobs in significant numbers the recession has already begun. Payroll numbers are also a lagging data point that gets revised—the first payroll decline in 2007 was originally reported as a gain and only revised down to a loss later. Still, the labor market remains a critical guide—in particular, both of the last two recessions in the US were preceded by slow declines in prime age employment rates before the recession sent employment levels tumbling. That’s what makes the fact that prime age employment levels have functionally not moved in 4 months a bit worrying.

Unemployment insurance claims are our best live view of the labor market even if they are rougher datapoints. Since the start of this year we have seen a rebound in initial unemployment claims and a bottoming of continued unemployment claims, although both remain near historical lows.

We are seeing the first signs of deteriorating hiring plans among firms in the manufacturing sector. Local manufacturing indices from the Federal Reserve show future employment levels still growing for manufacturing firms across the board—but at the lowest pace since the start of the pandemic. More worryingly, all three surveys from the above chart are showing current activity declines—so employment could just be a lagging indicator again as business conditions deteriorate.

Service sector employment expectations seem to be holding up better—which is good news since a much larger chunk of American employment is in the service sector. This is likely in part due to a more optimistic outlook for demand as consumers possibly rebalance from goods to services throughout the summer. Still, current business activity for services firms also remains weak or decreasing, so employment again may only be a lagging indicator—though the ISM services PMI already has already shown a dip in employment.

Keep in mind that FOMC members are forecasting a half-percent increase in the unemployment rate is necessary in order to get inflation under control—an amount that would represent a small-recession-scaled downturn.

Conclusions

Forecasting recessions is, again, extremely hard—and it is difficult to come across both appropriately worried and appropriately uncertain given the large number of factors influencing the economy. Outcome variance is extremely high right now, and that should be acknowledged in any assessment of the nation’s economic health.

Still, it is worth thinking through the different possible severities of a hypothetical slowdown or recession. History is just as often a chain as a guide—if we do have a recession, and again that is a big if, it will likely not resemble the recessions of the past simply due to the unique economic situation America currently finds itself in. But just for communication’s sake, let’s compare to prior recent slowdowns and downturns.

The 2018 scenario is one in which the Fed reacts early to deteriorating financial and economic conditions and swiftly reverses course on its policy outlook. Unless you are an avid watcher of economics or financial markets, it was likely possible to avoid knowing about this downturn altogether—employment growth remained relatively stable, wage growth was still high, and output growth only wavered slightly.

The 2016 scenario is one in which economic conditions continue deteriorating to a significant slowdown but avoid an outright recession. Output declines are substantial but concentrated among manufacturing sectors and outside of America’s wealthiest cities. Job growth slowed but never stalled and wage growth takes a bit of a dip but recovers relatively swiftly. A slowdown in nonresidential investment negatively affects growth and financial markets remain jittery, but further output declines are avoided.

The 2001 scenario—which I do not think is likely at this point—is one in which efforts to combat inflation cause a significant and broad-based recession. Employment levels shrink and unemployment rises several percent, wage growth drops dramatically, a large number of firms go under, industrial capacity permanently shrinks, and it takes several years before economic growth approaches “normal” levels again.

The “soft-ish landing” scenario where inflation comes down without rough economic pain or an extended downturn appears to still be the most likely option. No matter what happens, though, it will remain critical to watch economic data in order to continually evaluate the possibility of a recession.

Thank you for your posts. I find your reasoning clear and insightful, and I appreciate you citing the data sources, which helps me follow up. (And thank you for explaining nuances in various data series!)

Toward the end of this post you write, "The 2018 scenario is one in which the Fed reacts early to deteriorating financial and economic conditions and swiftly reverses course on its policy outlook." Do the Fed and US government have less room to adjust policy today compared to in 2018? In particular, do current high inflation and low real interest rates force the Fed's hand to continue monetary tightening, more or less regardless of how the real economy responds, until inflation comes down to "reasonable" rates? Is there justified concern that historically high levels of national debt, globally, will interact with inflation, especially as central banks raise interest rates?

I think this is the best post in a while about the current state of the economy, just because we are comparing the data now with the data during / right before past recessions. Even though every recession is different, how useful an indicator is seems to be determined by how well it actually indicates for past, similar recessions.