We Have a Chance to End America's Great Employment Failure

America Used to Be an Employment Leader. For American Workers' Sake, it Must Lead Again.

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Thanks for reading. If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 5,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

Regular readers of Apricitas will know that I focus heavily on the labor market as both an indicator for the state of the US economy and a goal for policymakers to influence. I believe—with good reason—that wages, work, and employment are the most important parts of economic well-being. The labor market is the market of markets—businesses depend on labor for basic function, workers depend on labor income for their consumption, investments require labor to make them valuable, and governments require labor to ensure the functioning of the state. Nearly every firm and household must, at some point, engage with the labor market. So much of prosperity at an individual and household level comes down to your employment, job security, and wages. Indeed, the most powerful countries in the modern world are not the ones with the largest natural resource reserves or the biggest armies but those with the best and most productive workforces.

That is why the last 25 years have been modern history’s biggest tragedy. A series of poor macroeconomic policy choices have resulted in decades of shrinking employment and lost wages across many high income countries—but especially in America. During the late 1990s, America’s labor market was arguably the strongest in the world. The 2001 and 2008 recessions left it permanently scarred—and now America significantly lags many of its peer countries.

For the sake of America’s workers, it must lead again.

Yesterday’s jobs report showed the unemployment rate holding steady at 3.6%, approaching the lowest rate in 50 years. This represents an exceptionally fast recovery from the high of nearly 15% set in April 2020, especially considering that America did not employ the kind of job retention schemes that protected employment in other high-income nations. We truly have returned to the strong labor market of late 2019, but we also have an incredible opportunity to finally push for something greater.

America’s Great Employment Failure

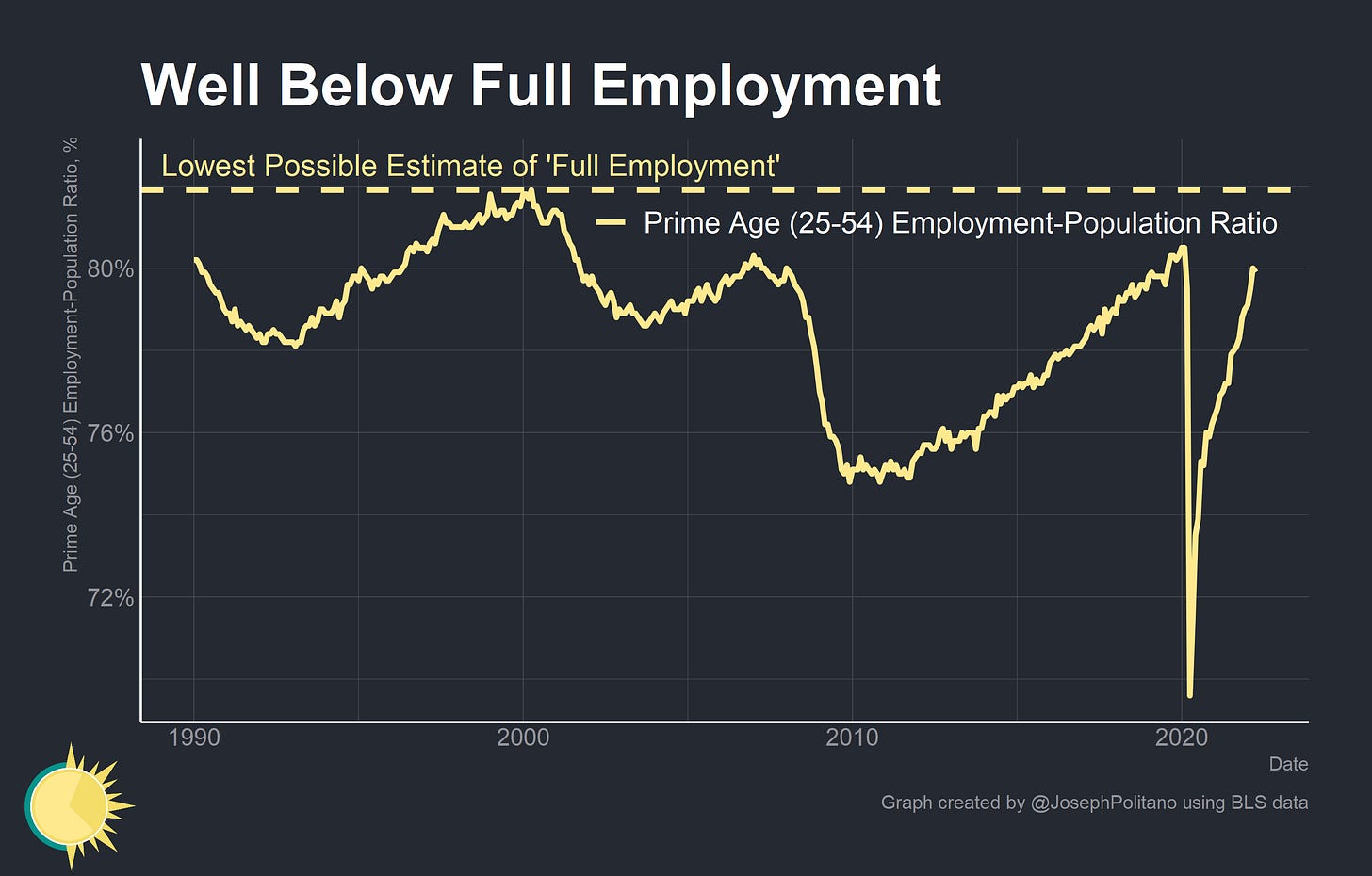

Unemployment rates are the headline-grabbing parts of jobs day, but it is employment rates that are actually the better indicator of labor market health. Workers outside the labor force are not counted as unemployed, but many of these people want a job but have given up searching (especially in recessions). The prime-age (25-54) employment-population ratio measures the percent of working age people who have a job, so it accounts for both age and labor force composition biases. That number has hovered near 80% for the last two months, close to the pre-pandemic level but well below the 82% achieved at the turn of the millennium. America is still lagging its past achievements.

Not only that, but America is increasingly falling behind its peer nations. In the 1990s, America was a leader in employment levels thanks to its strong economy and relative accessibility to working women. The 2001 recession and the “jobless recovery” that followed knocked America back down to a level more in line with its peer nations—and then the 2008 recession knocked America far behind. Today, Italy—a nation notorious for its perennially broken labor market—is the only member of the G7 with lower prime age employment levels. Countries like Portugal and Japan—which have by no means experienced surges of dynamism or explosive economic growth over the last two decades—have managed to beat out the US and achieve 85% prime age employment rates.

Focusing on the nations most similar in legal and economic policies shows how badly the 2001 and 2008 recessions scarred America. America lead all of its closest peer nations throughout the 1990s, but fell to the middle of the pack by the mid-2000s. The 2008 recession wrecked the American labor market, sending it to the bottom of the pack—where it remains stuck today.

In the 1990s America was a relative leader in terms of female employment. The 2001 recession forced many women out of the workforce and allowed the US to slide behind some of the other leaders. Then the 2008 recession devastated female employment, sending it below 1990 levels until the late 2010s. Japan—a country that used to be infamous for its low female employment rates and hostility towards working women—surpassed America in female employment rates around 2012 and has since vastly exceeded even America’s 2001 highs.

Male employment has been declining across advanced economies as men spend more time raising children and employment transitions away from traditionally male-dominated industries like manufacturing. Still, in few countries has the decline been as stark and as dramatic as in the US. Male prime-age employment rates in the US were nearly 10% off all-time-highs in 2009, and still remain 5% below their high-water mark.

Fundamentally, America lacks the institutionalized employment protections that many high-income nations have. When the pandemic struck, countries across Europe used the government’s tab to institute furlough and job retention schemes to keep workers in place despite the economic slowdown. The US has no such capabilities (hence the scramble to implement enhanced unemployment benefits at the start of the pandemic). The end result is that recessions in the US manifest as massive declines in the workforce. Couple that with the relatively weak policy responses to the 2001 and 2008 recessions and you have a situation where labor demand and employment remain artificially low for more than two decades. The good news is that the COVID recession saw by far the strongest and swiftest policy response in American history, allowing employment to recover to pre-pandemic levels in two short years. Still, there are millions of people who could be brought into employment in the next stage of the economic expansion. It will be to America’s great benefit if these people are brought into the workforce.

Idle Hands

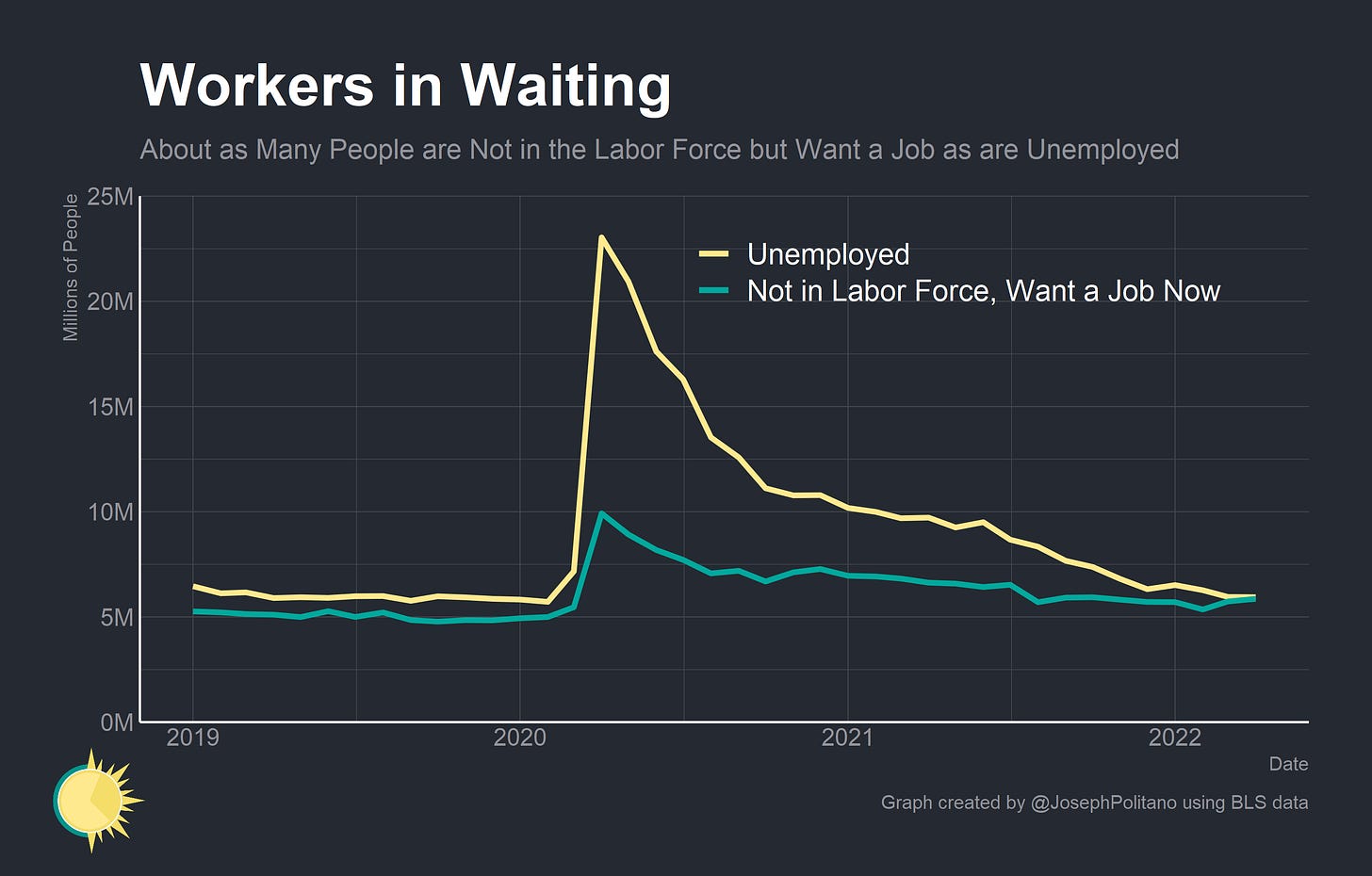

Early in the pandemic, a wave of temporary layoffs caused employment to surge as the entire country entered lockdown. Over the course of 2020, the vast majority of those temporarily laid off either returned to work or became permanent job losers. By late 2020 those permanent job losers made up the majority of the unemployed—and the number of permanent job losers exceeded the height of the 2001 recession. The good news is that the much stronger response from fiscal and monetary policymakers reduced unemployment to pre-pandemic levels. With unemployment so low, some believe that the labor market has achieved full employment. After all, where could additional workers come from if not the unemployed population?

The answer is workers outside the labor force. Unemployment, at least in the official statistical sense, is a lot less clear cut that most would initially suspect. In order to be counted as unemployed a person must

Not have a job

Have actively looked for work in the last four weeks

and be currently available for work

Unsurprisingly these qualifications mean that many people who want to work are not counted as unemployed. About five million people are not in the labor force but say they want a job today, and these people are not counted as officially unemployed even though by any colloquial definition they would be considered unemployed. That’s another massive pool of possible workers that could be drawn into employment if labor demand remains strong.

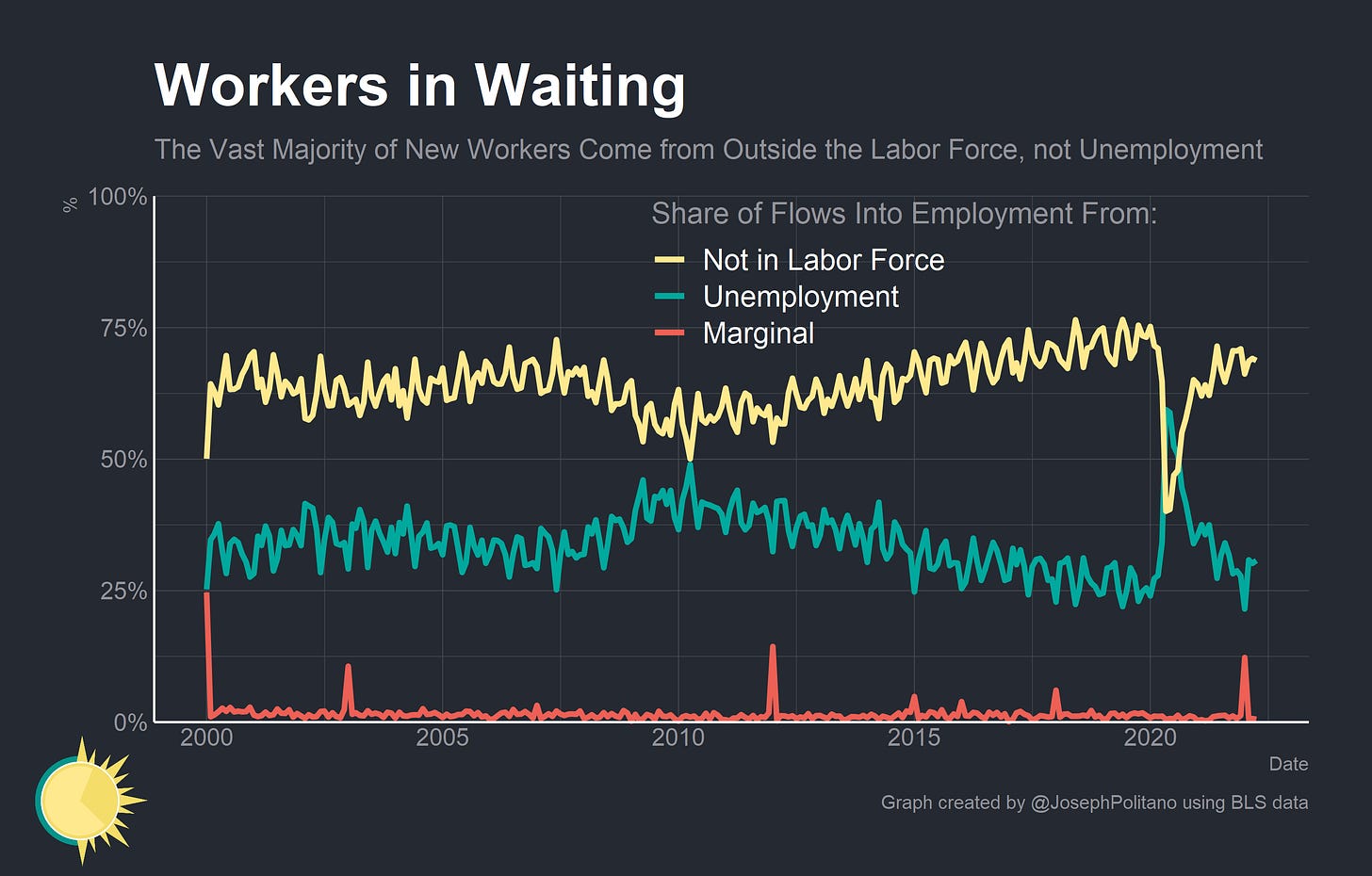

In fact, the majority of flows into employment every month do not come from unemployment but rather from outside the labor force. This is true during all but the very worst recessions (i.e., early 2020), but during boom times nearly 3/4 of all flows into employment come from outside the labor force. Granted, that’s partially because the number of Americans outside the labor force is just so large (about 100 million people compared to about five million people in unemployment), but it also reveals how rapid growth in employment numbers can occur despite low unemployment numbers.

American economic policymaking and punditry has a horrible history of presuming that workers outside the labor force are lost forever. In the 2010s drops in employment for non-college educated people were blamed on a “skills gap”. Drops in employment for young people were blamed on their laziness. Drops in employment for men were blamed on video games. By the late 2010s employment rates had basically recovered to pre-recession levels for all of these groups, proving that it was artificially weak labor demand keeping them out of the workforce. When companies increased their hiring intensity and wages began rising, many of these workers were drawn back into employment. During the pandemic we saw a microcosm of this regarding workers who were pushed into early retirement due to COVID. Policymakers and forecasters worried that these workers were out of the labor market for good, but as COVID abated and labor demand recovered many of these workers have since reentered the workforce. We shouldn’t discount the possibility of future employment gains just because those workers would come from outside the labor force instead of unemployment.

What Could You Do With An Extra $9,600 a Year?

In 2019 Americans earned, on average, about $9,600 less than they would have if growth had continued at the pre-Great Recession pace. Matt Klein puts it best: “Americans have been living below their means—producing, consuming, and investing less than they otherwise could have—for 15 years.” Much of that drop in earnings came from an inability or unwillingness from policymakers in Congress and the Federal Reserve to pursue the kind of aggressively stimulative monetary and fiscal policies that caused the post-COVID employment recovery to be so rapid. Think about all the buildings that went unbuilt, the skills that went undeveloped, and the inventions that went uninvented because America chose to idle tens of millions of workers—its most valuable resources—for decades.

Inflation has, understandably, taken center stage in today’s macroeconomic policy debate. As the Federal Reserve tightens monetary policy to reduce inflation, it is likely that the rate of employment growth will also slow. Truth be told, the rate of employment growth was always bound to slow at this point simply because the vast majority of previously-employed people have returned to work. The key remains to balance the need to combat inflation with the need to expand and strengthen America’s workforce. We have an opportunity to end America’s decades long employment failure, and it’s an opportunity we simply can’t afford to pass up.

It is hard to explain Japan being the #1 employer given it has been the worst performing economy (in terms of real growth) for the past 30 years!

Great article. To bear in mind after J Powell press conference where he insisted in labour market tightness. Happy to be a suscriber. Wonder how the US can go back to full capacity (those 9.160 usd…) without scaring inflation hawks in government & markets.