What Does a Labor Shortage Mean?

It's About Workers' Wins Just as Much as Businesses' Woes

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 20,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

If you’ve read the economic news or talked to any small business owners, you’ve likely already heard how difficult it is to hire—companies have been complaining about recruiting struggles and ongoing labor shortages for more than two years now, with little reprieve. Those hurt most by the pandemic—front-facing service-sector companies in industries like food service and entertainment—were the first to cite worker shortages as a major problem, but the situation then rapidly became widespread. Hospitals, manufacturers, schools, airlines, and even tech companies have been increasingly held back by a persistent inability to hire adequate staff. This summer, 50% of American small business owners reported at least one unfilled position—and 35% cited labor quality or labor cost as the single most important problem facing their business.

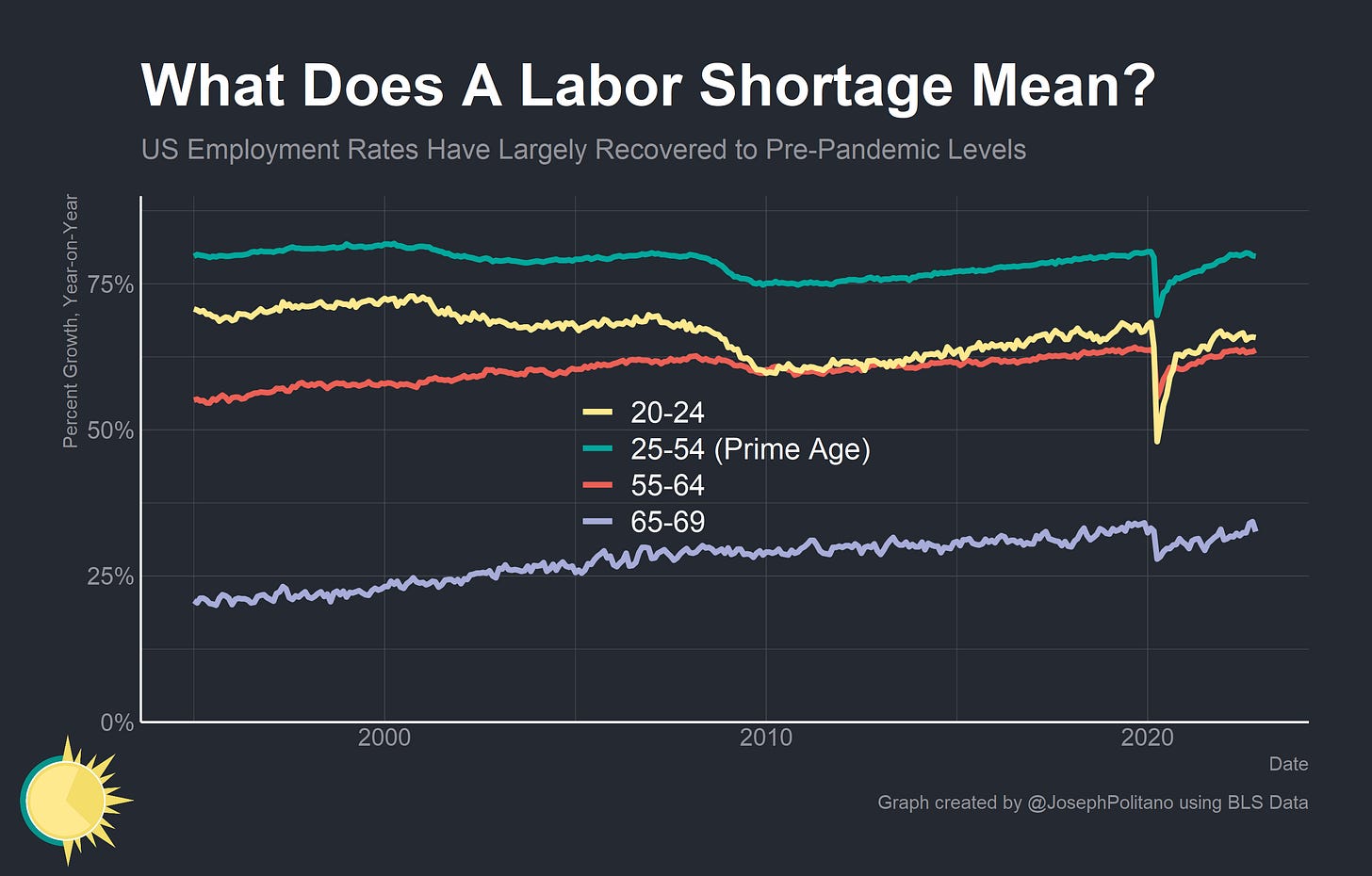

But of course, employment dynamics are a two-way street—a labor shortage is just a worker’s job market, and today’s historically strong labor markets come just after decades of stagnant wage growth and excess unemployment. The last two years have seen record-high wage growth, especially for the lowest-income workers, and the fastest pace of job gains in modern history. Employment rates have now essentially fully recovered to pre-pandemic levels and massive numbers of workers have been able to start new, higher-paying, more productive jobs.

Today, those economic gains are at significant risk. Wage growth, employment growth, and aggregate labor income growth have been so strong that they are pushing inflation above the Federal Reserve’s 2% target—and with inflation so high, Fed Chair Jerome Powell has repeatedly signaled that he believes significant labor market deterioration will be necessary to get inflation back under control. With the job market at a critical turning point, it’s more important than ever to understand the unprecedented dynamics that drove America’s labor shortage.

The Great Reshuffling

“The Great Resignation” was another term bandied about to describe the unprecedented labor market dynamics of late 2020 to early 2022—the rate of Americans leaving their jobs surged past pre-pandemic levels, especially in low-pay industries like food service and retail trade. The vast majority of these quits, however, involved job-to-job transitions—not workers exiting the labor force, but workers exiting their current job for better-paying opportunities at other firms or industries.

In fact, there has been a nearly-full employment recovery across prime-age and non-prime-age populations—all at the fastest pace on record. The only age group with significantly worse employment levels are those at the very edges of the age distribution—those 70+ who were most at-risk for COVID and most likely to retire alongside those 16-24 who were most likely to have disruptions or delays placed on their academic lives. That is a remarkable achievement, especially placed against the massive labor supply disruptions from illness, childcare obligations, family obligations, and death caused by the pandemic.

But if these quitting workers aren’t actually leaving the workforce, where are they going? For the first time since the start of the pandemic, we can actually answer that question quantitatively. The Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Employer Dynamics (LEHD) program combines comprehensive administrative data with censuses and surveys to determine precisely where workers are moving to and from throughout the economy, broken down by city, age, gender, industry, and more. We don’t have complete data—with some states not yet reporting1 and the updates only going through Q3 2021—but we can finally get a clear picture of what labor market dynamics looked like at the very height of the labor shortage.

So where were quitting workers going? Increasingly, they were going to higher-paying, more professionalized jobs. The share of workers in low-pay service sector industries moving into higher-paying, white-collar industries surged to a recent high at the tail end of 2021. These kinds of job-ladder transitions are important for long-term economic growth, though they by no means make up a majority of job-to-job moves. At all times, most movements occur within-industry, though the motivations are mostly the same—workers searching out higher paying jobs that are more productive.

Employees were also increasingly moving from America’s small businesses to its big businesses. Large companies tend to be more productive and professionalized thanks to the economies of scale in the industries they operate in, and they also tend to have better pay packages and more upwardly-mobile positions to offer new employees. At the height of the labor shortage, job-to-job transitions from small businesses to big businesses hit a new high—and actually exceeded job-to-job shifts between small businesses. That’s a major change that makes it partially clear why small businesses have voiced such strong frustration with the labor shortage—they have been getting out-competed on labor costs and productivity.

The geography of American jobs also changed radically since the start of the pandemic. In the major housing-constrained market of states like California and New York, a stronger nationwide labor market tends to accelerate outmigration as lower-income workers are priced out of major cities by rising housing prices and enticed by stronger job prospects in more housing-abundant metros. Net job-to-job flows into states with lower-cost housing markets (such as Texas, Florida, North Carolina, and Georgia) essentially doubled after the start of the pandemic while flows from California to Texas in particular rose to a new record high.

Who was leaving the high-cost states also changed in an important way—Historically, college-educated professional workers were moving into the superstar cities of San Francisco, New York, and Los Angeles while lower-paid and non-college-educated workers were decamping for cheaper, growing cities. But the pandemic and remote work caused many highly-paid professionals to look for new jobs outside of big cities, hence the significant surge in outmigration from college-educated and white-collar workers.

The end result of a lot of this job-hopping among American workers was rapid pay increases, with median wage growth for job-switchers closing in on 8%, the highest level in more than twenty years. Rates for job-stayers also accelerated to 5.5% amidst the increased competition for labor—worried about the increasingly-credible threat of employees leaving the company, employers were willing to raise nominal wages at extremely fast rates.

Wage gains were also highly progressive, with lower-income workers receiving rates of pay growth significantly faster than their higher-income counterparts. Given how significantly low-income workers’ pay is tied to cyclical economic factors, it’s not surprising that they saw the most gains in the labor shortage—but the degree to which they’ve benefitted is astonishing. Arguably, the only group to see real wage gains since the pandemic has been low-income workers, with workers in the bottom 10% seeing very strong real gains. The labor shortage has also enabled rapid wage gains for young, non-white, non-college-educated, and part-time workers to a degree that is nearly historically unprecedented, and was helping break America out of the cycle of labor market underperformance it suffered throughout the 2010s.

A Shortage, If You Can Keep It

Of course, this extreme labor market strength has pushed up cyclical inflation (especially in housing) to a degree that was causing problems for the Fed’s inflation-fighting efforts. There is an upper limit on the amount of nominal growth possible before significant inflation kicks in—and last year certainly exceeded that limit. Since 2021, the labor market has untightened significantly with wage growth declining in low-pay sectors and quit rates falling back down closer to the upper end of normal than new record highs. Growth in gross labor income—GLI, the sum of all wages and salaries in the economy—vastly exceeded the pre-pandemic growth trends in 2021 but looks to be quickly declining back to normal levels this year.

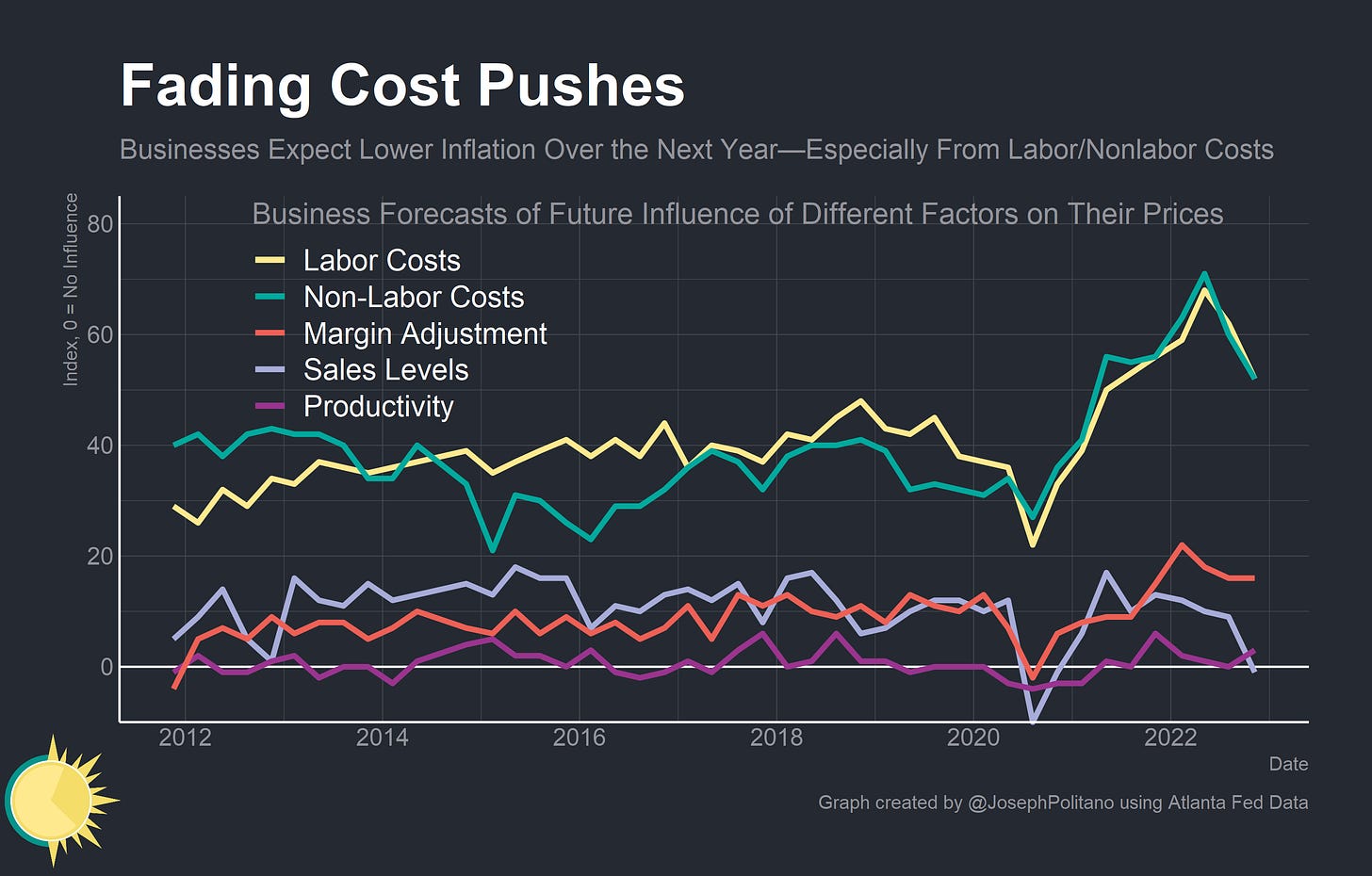

Businesses are seemingly feeling less stressed about the labor shortage too, with the share of small businesses with unfilled positions declining alongside a 5% drop in the share calling labor quality their most important problem. Companies in the Atlanta Fed’s business inflation expectations survey believe labor costs will contribute less to unit-cost inflation over the next year—tied with the contribution amount they expect from nonlabor costs and only marginally above the pre-pandemic high for labor’s cost contribution.

The task for Jerome Powell, and the big question surrounding monetary policy, is whether they will be able to restrain inflation and aggregate income growth without triggering a recessionary increase in the unemployment rate. Right now, they don’t see that as a likely possibility—though it remains the ideal outcome. That’s because the labor shortage has meant significant growth for American workers and the American economy—which is not something worth giving up lightly.

Specifically, Alaska, Arkansas, Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Nevada were excluded from all LEHD calculations for data availability reasons.

Terrific review of labor and its impact on inflation and workers. Thanks Joseph

Super insightful. I’ve been challenging those who still like to place sole blame of the labor shortage on the unemployment checks people got during the pandemic “they’re getting paid not to work.” Yet they couldn’t offer an explanation for non-service/low wage labor shortages. Fair to give them some grace in that this data is now just available to be digested.