What Killed Signature Bank?

Signature Bank's Overlooked Failure Was Still the Third-Largest in US History. What Killed New York's Premiere Crypto Bank?

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 24,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

On Sunday, March 12th, US regulators stepped in to prevent a nascent crisis in America’s banking system. They decided to make depositors at then-defunct Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) whole and, at the same time, announced they’d be closing down New York-based Signature Bank and making its depositors whole. The simultaneous initiation and resolution of the crisis for Signature’s depositors, alongside Signature’s much smaller size compared to Silicon Valley Bank and its relatively quick sale to Flagstar Bank, meant the institution’s failure didn’t garner as much press. But Signature’s collapse is worth analyzing in its own right—were it not for SVB, it would have been the second-largest bank failure in American history, even larger than the 1984 collapse of Continental Illinois.

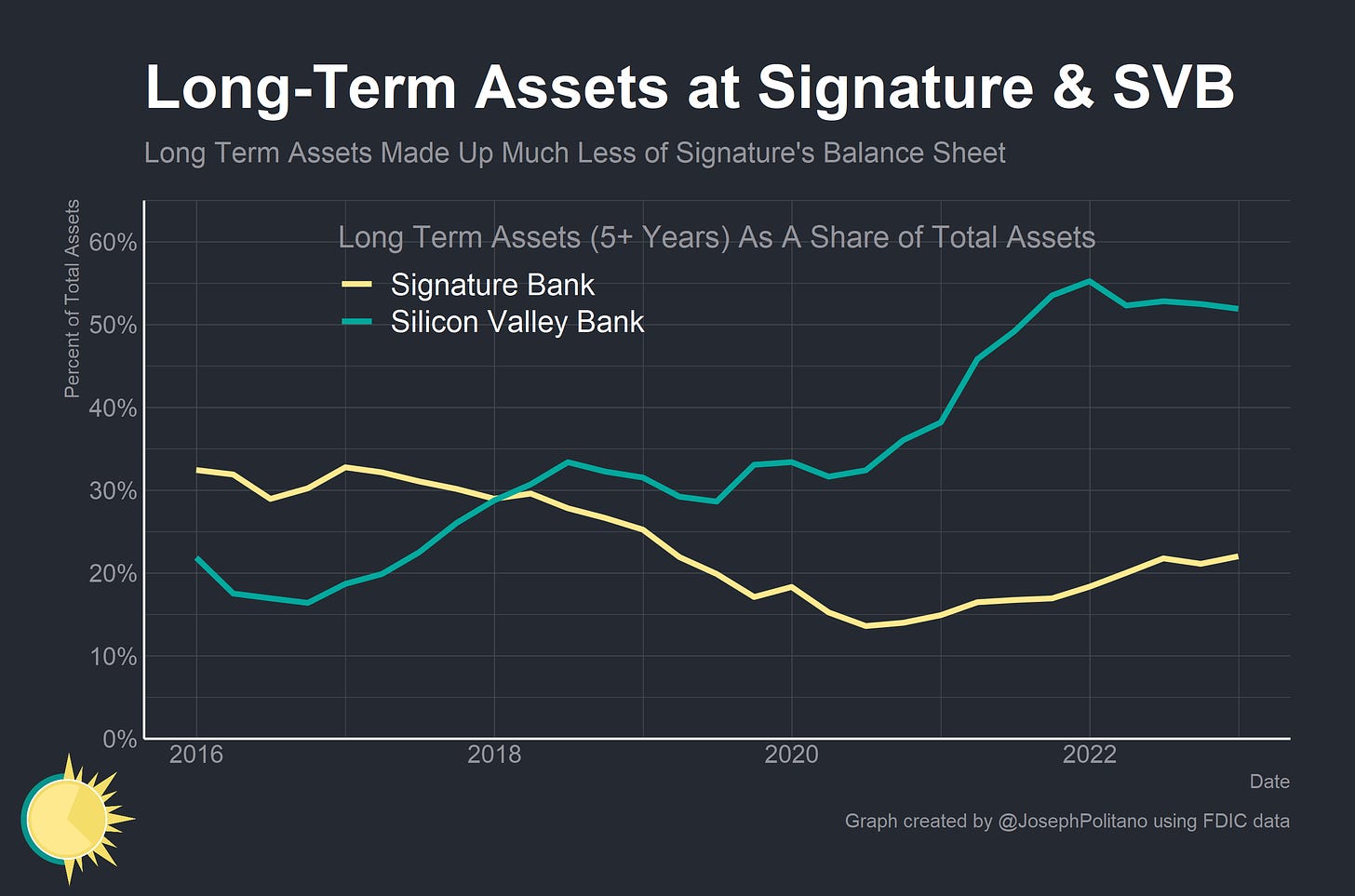

Plus, Signature did not have precisely the same underlying problems as SVB—although both banks had concentrated depositor bases, a large share of uninsured deposits, and had sustained significant losses and deposit outflows in recent quarters, Signature did not make the same kind of large unhedged bets on long-term assets that crushed SVB when interest rates rose. Instead, it had a more concentrated exposure to New York commercial real estate and private equity lending markets and was a key player in the crypto industry, all of which made it weaker than most but stronger than SVB in the current market environment. That meant Signature entered the crisis on better footing than SVB—but that still wasn’t enough to save it. Both institutions met their demise in largely the same way—rapid withdrawals from uninsured depositors that eventually simply became too much for the banks to survive.

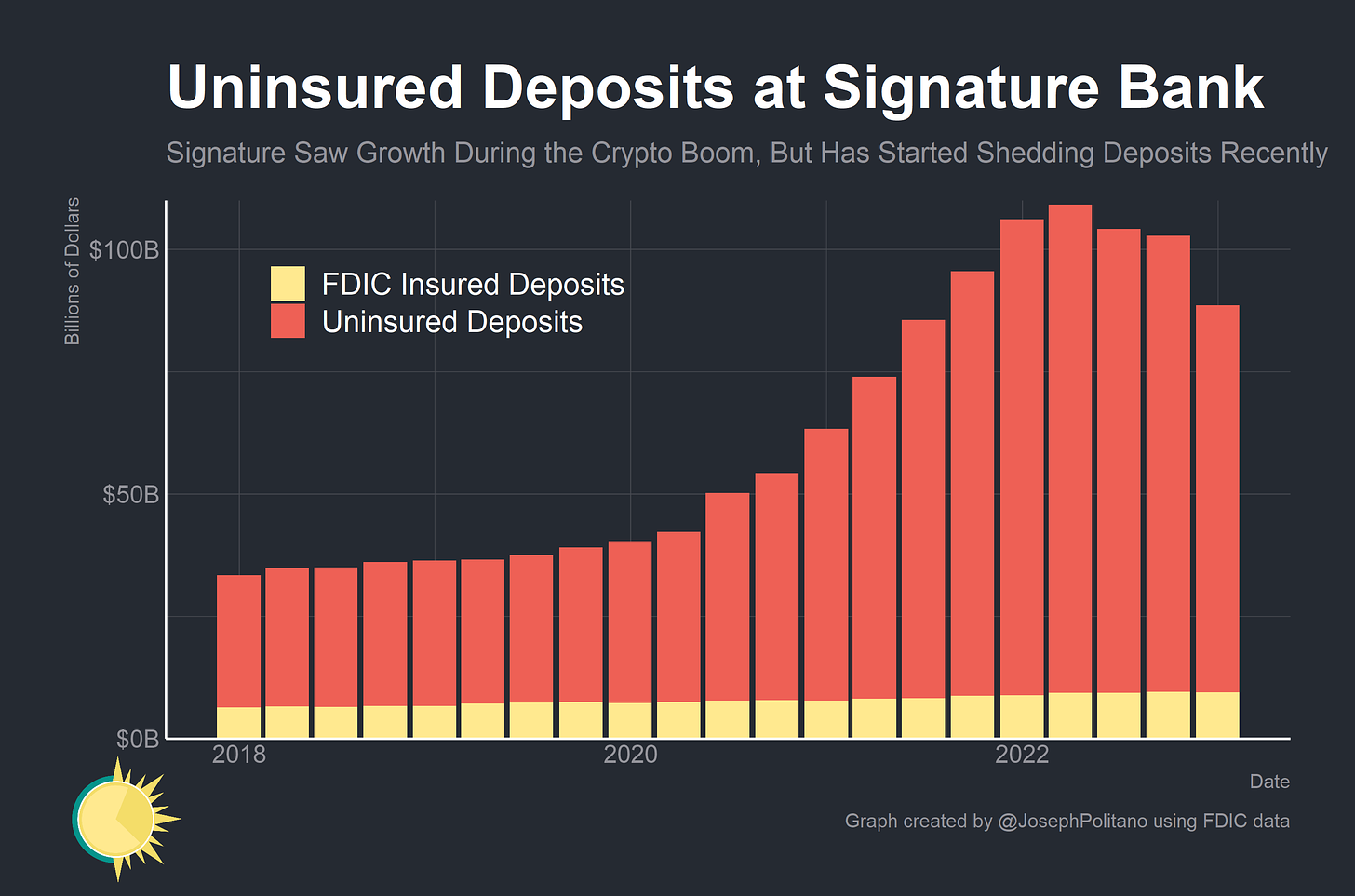

Something More Than A Crypto Bank

Like SVB, Signature Bank saw extremely large deposit growth during the start of the pandemic, with total deposits reaching triple 2018 levels by early 2022. Plus, like SVB, the vast majority of Signature’s depositors exceeded the $250,000 limit on FDIC insurance for US bank accounts. That’s because the bank’s primary customers were commercial real estate companies, high-end white-collar businesses, and private equity firms that all boomed during the early pandemic. Perhaps Signature’s most notable relationships, however, were with cryptocurrency companies—the firm’s digital asset banking team worked with major players in the crypto ecosystem early in the industry’s boom years and developed Signet—an proprietary 24/7 365 blockchain payments network for its institutional crypto partners. Signet’s users included industry giants Binance, Genesis, and now-defunct FTX & Alameda Research.

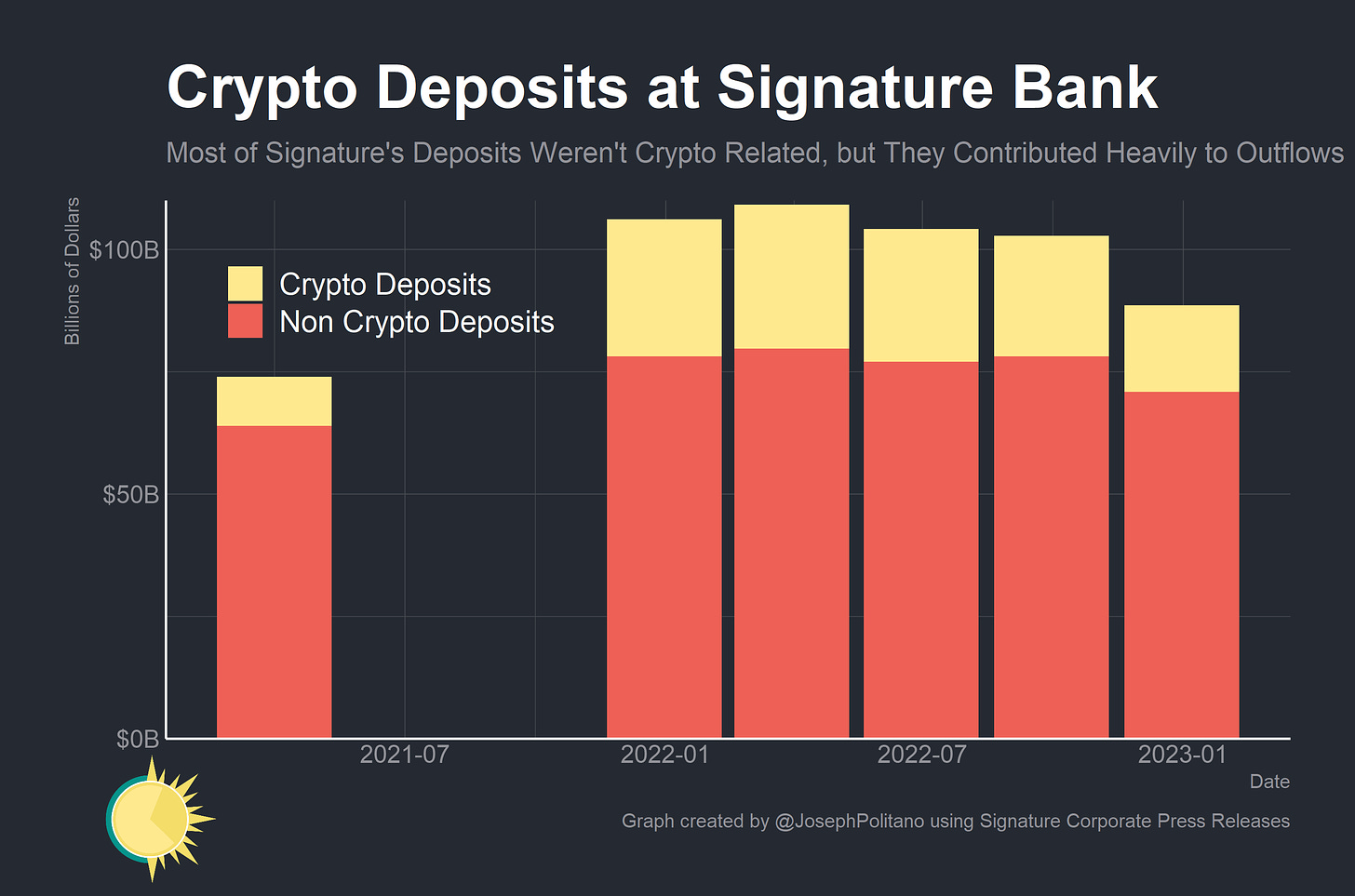

Those crypto deposits had started to leave just as quickly as they came, however. In early 2021, when Signature first began reporting the deposits of its digital assets banking group separately, the company had $10B in crypto-related liabilities. By early 2022 that ballooned to $29B—more than a quarter of total deposits—before starting to gradually sink throughout the crypto winter of 2022. The fall of FTX hurt the digital asset group the most, with crypto deposits falling $7B in Q4 2022 alone. At that point, total crypto-related deposits stood at $17B, about 1/5 of the bank’s total, and the outflow likely only accelerated from there. We can’t come up with an exact timeline, but as of the successful sale of Signature Bank to Flagstar Bank on March 19th, only about $4B in total digital asset deposits remained. The vast majority of these deposits were likely uninsured and fled as soon as trouble began brewing at SVB.

That rapid flight is somewhat counterintuitive because Signature did not have the same broad risk profile as SVB, aside from the high share of uninsured deposits. Where Silicon Valley Bank was piling into long-term fixed-income assets in 2020 and 2021 only to be caught off-guard by rising interest rates, Signature was reducing its concentration in long-term loans and securities throughout most of 2018/2019 and kept overall duration exposure low throughout the pandemic.

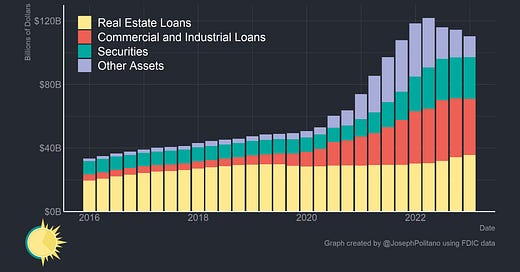

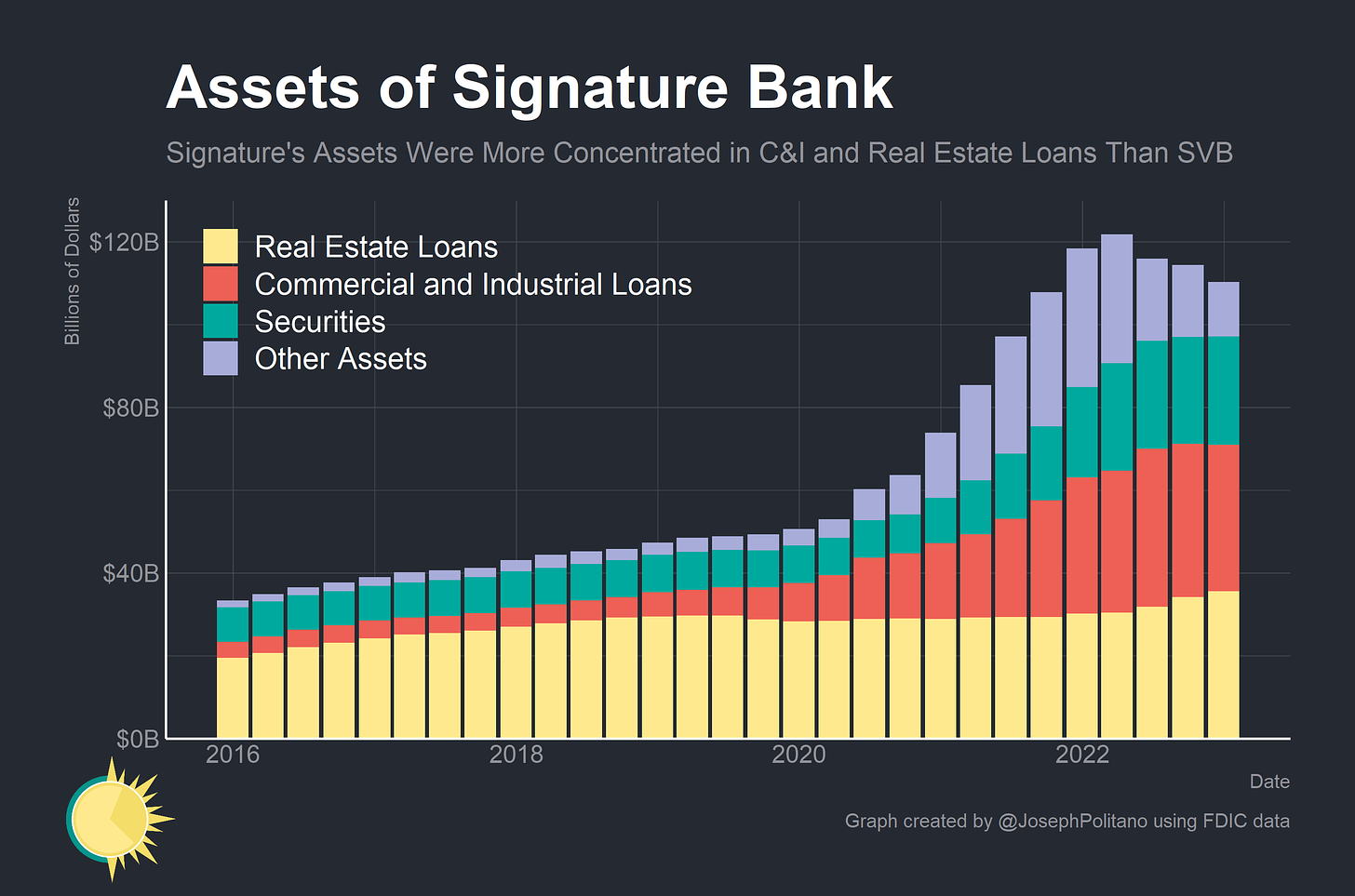

Indeed, most of the pandemic-era growth on the asset side of Signature’s balance sheet came from large growth in commercial loans, with some assistance from securities and other assets (mostly cash). That preexisting real estate exposure mostly represented loans to multifamily and commercial properties in the New York area, and the explosive growth in commercial and industrial loans mostly represented the expansion of the firm’s private equity lending division.

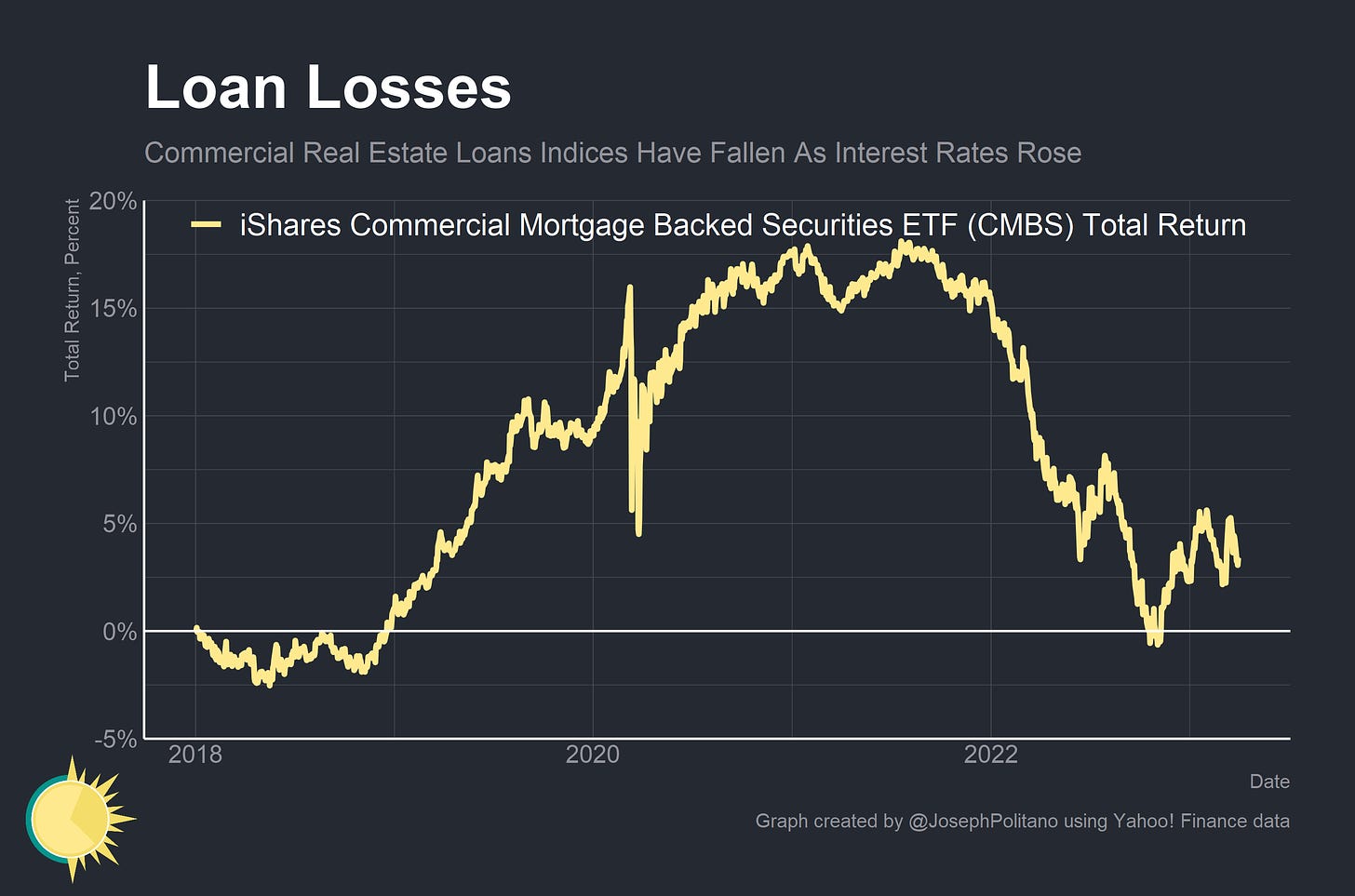

Both of those major industries—New York real estate and private equity lending—have not exactly had the best run recently, especially as interest rates began increasing in early 2022. Commercial Mortgage Backed Securities Indices fell significantly since early 2021 as rates increased and recession fears grew, and private equity valuations have likely fallen significantly based on what we know from public data.

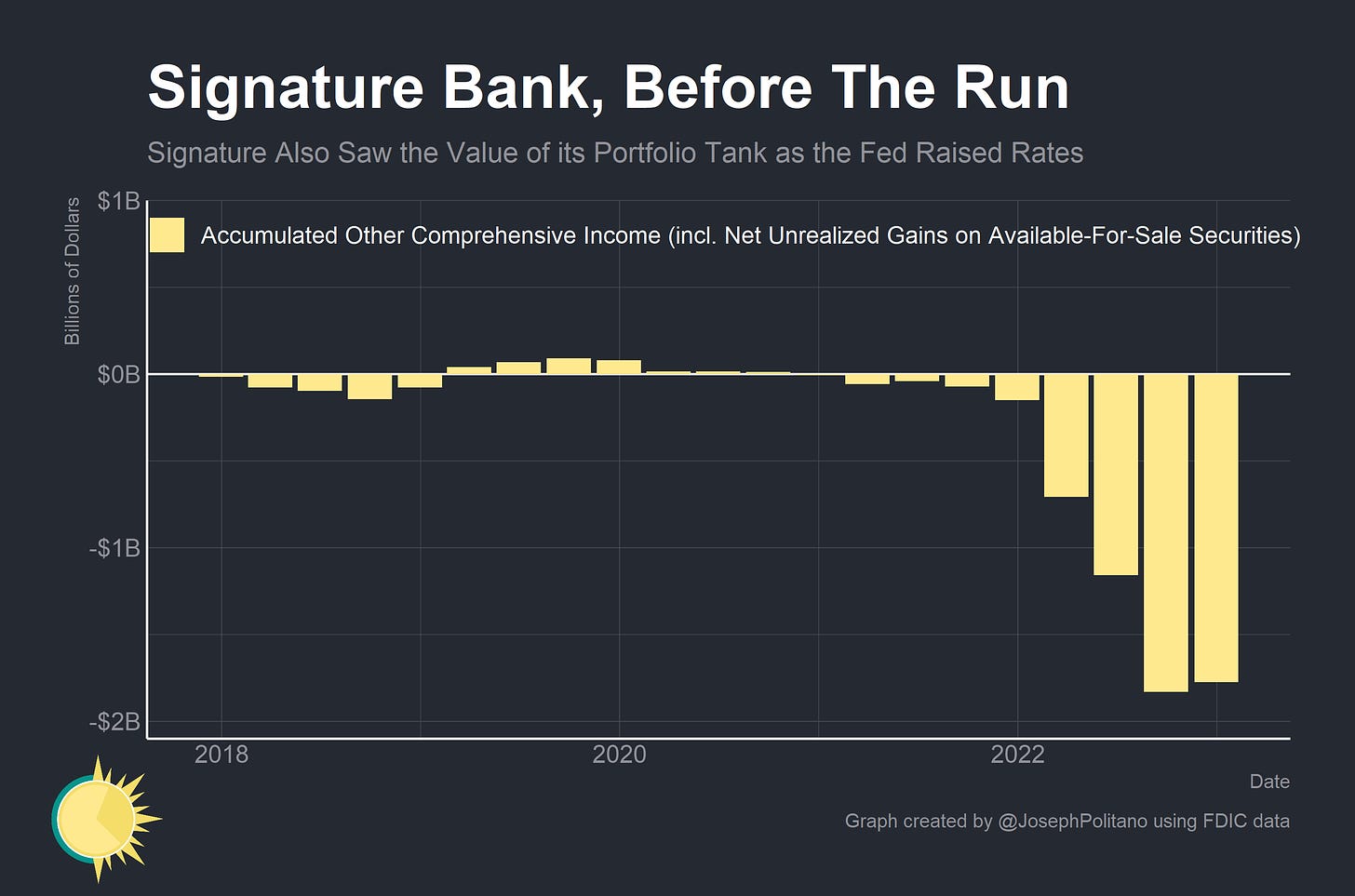

Plus, Signature did still have losses on its securities portfolio that were fairly significant compared to the size of the company. Signature’s Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income, which includes unrealized losses on banks’ available-for-sale securities, had fallen to negative $1.7B by late 2022, representing a large chunk of the bank’s equity capital.

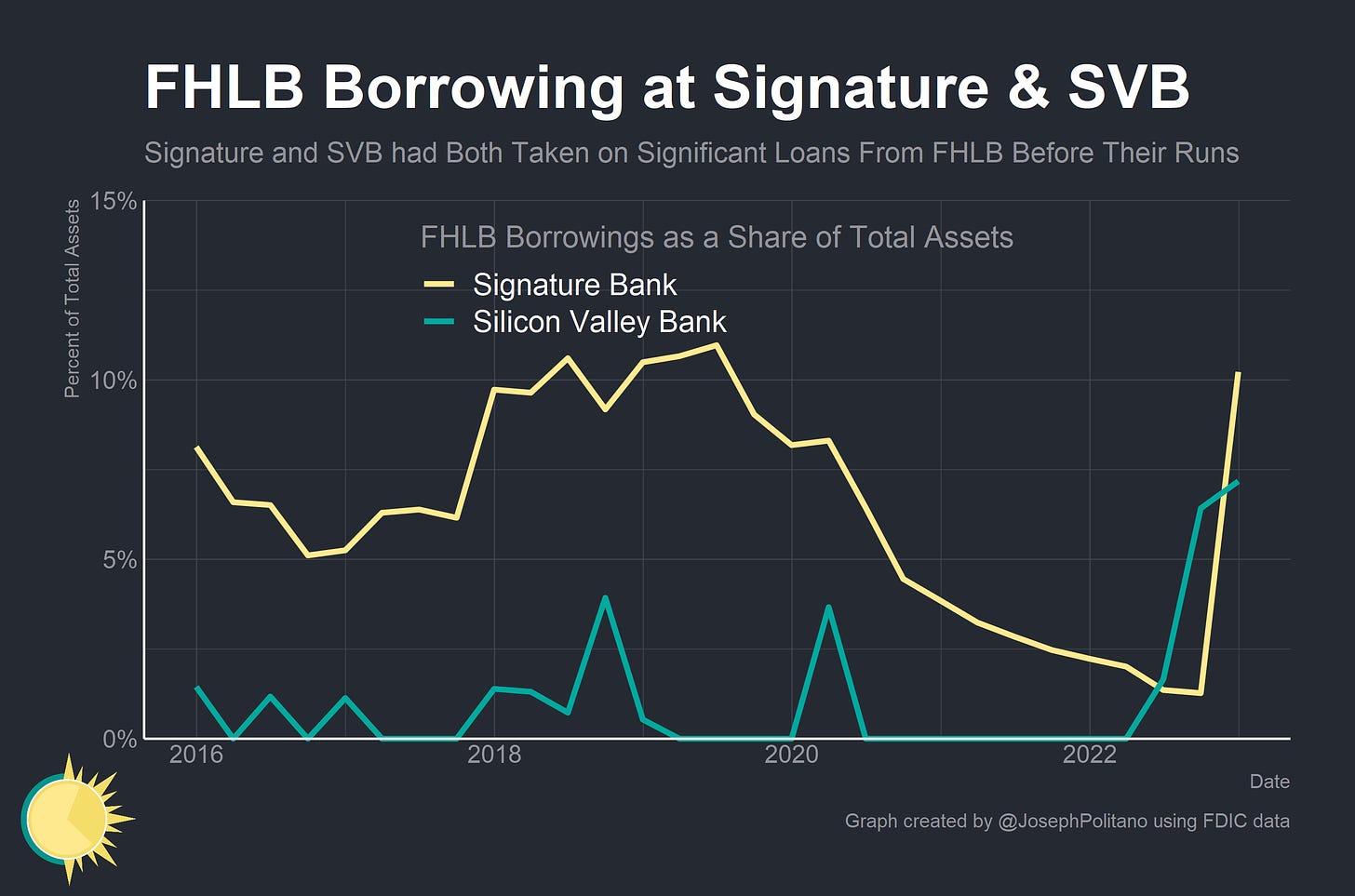

Signature Bank was also already borrowing from the Federal Home Loan Banks, institutions that serve as lender-of-next-to-last-resort for banks with liquidity needs that aren’t quite dire enough to justify borrowing directly from the Federal Reserve. In fact, at the start of this year, Signature was borrowing proportionally more from the FHLBs than SVB, although its involvement in the real estate industry made it a more frequent baseline user.

Still, Signature’s overall position was not nearly as bad as SVB’s going into the year—on the asset side Signature was much closer to a normal bank than SVB, and even on the liabilities side it was much more diversified. Signature’s losses, while large, still left the bank in a comparatively well-capitalized state, and the bank was already undertaking active steps to diversify away from crypto deposits in the wake of FTX’s collapse. So Signature was definitely at risk, but markets at the time believed it was in a much stronger position than SVB and even still-surviving banks like Pacific Western. That, unfortunately, wasn’t enough to save the institution from a textbook bank run that began on Friday and continued until the bank’s closure on Sunday.

The Textbook Bank Run

No bank can survive a critical mass of depositors leaving in an extremely short amount of time—a bank’s fundamental business model requires balancing liquid short-term liabilities with more illiquid longer-term assets, and if everyone demands their money back at once the best institutions can hope for is an orderly wind-down where creditors are made whole. In Silicon Valley Bank’s case, testimony from Federal Reserve Vice Chair of Supervision Michael Barr revealed that depositors tried to withdraw $100B on the day of the bank’s failure, which combined with the $42B withdrawn the day before represented 85% of the bank’s total deposits. For all but the most narrow, conservative banks that level of illiquidity means insolvency, which is why systems like deposit insurance are designed to prevent these kinds of massive bank runs in the first place.

Signature Bank wasn’t quite in the dire straights of SVB, but put yourself in the shoes of regulators that weekend—you have a bank that has an extremely flighty depositor base, reportedly lost 1/5 of its deposits in a manner of hours on Friday, continued receiving further withdrawal requests throughout the weekend, and had already exhausted most of its ability to borrow from the Federal Home Loan Banks and Federal Reserve. The bank could not give you accurate information on the current state of its finances, had been implicated in the FTX collapse, and was under investigation by the Justice Department and the Securities and Exchange Commission. Public trust was gone. Opening Monday meant certain death. Closing it over the weekend reduced the risk of further contagion, so it was decided that the bank would not open.

Conclusions

Flagstar Bank has assumed what remains of Signature Bank at a significant discount—although it left $60B of Signature’s loans in FDIC receivership. Flagstar likely left those loans on the table for a combination of reasons—wanting to limit their commercial real estate exposure, viewing the assets as worth less than their paper value, and just not wanting to grow super rapidly—plus the FDIC, unfortunately, tends to get poor prices by virtue of having to move entire banks through fire sales—but the outcome still suggests Signature had significant losses on its loan portfolio.

What’s most interesting is what Flagstar didn’t take—the remaining $4B in crypto-related deposits. That’s likely in part for legal reasons, but mostly for financial stability reasons—after witnessing three banks die in a manner of weeks thanks in part to their reliance on crypto deposits, would you be foolhardy enough to take on crypto depositors? Plus, between the start of January and the end of February US regulators put out two joint statements warning of the liquidity, volatility, legal, and contagion risks of crypto deposits to banks—there was likely some encouragement from regulators for banks to not take on the risks inherent in crypto overexposure.

This was, broadly, a correct assessment of the problem—the arrangement of having stablecoins and other crypto institutions be uninsured, unsecured, and concentrated counterparties of a tiny number of financial institutions did not work, and is partially to blame for recent financial turmoil. But at the same time, those cash pools aren’t going away—if they are just kicked out of the official US banking system, they will create demand in the shadow banking system to the benefit of less transparent, more systemically risky players in the crypto industry. The pools have to either be concentrated somewhere safe outside the banking system—say, in designated money market vehicles for stablecoins—or become balanced amongst traditional institutions in a way that disperses risks.

Still, the broader point is that crypto deposits themselves were not the sole source of the problem at Signature, which in many ways represented more of a generic bank run than Silicon Valley Bank. Depositors were concentrated at Signature but not as hyper-concentrated as at SVB, and losses were large at Signature but nowhere near as large as at SVB (the FDIC estimates that Signature’s failure will cost the deposit insurance fund $2.5B, significantly less than the $20B cost of SVB’s failure, despite SVB’s deposit base being only twice as large). Depositors just lost confidence in the institution in sufficient numbers to kill the bank, all within just a few days. Going forward, ensuring financial stability in the modern age is going to require managing the risks of lightning-fast bank runs, especially among uninsured depositors.

Very sobering article but informative.

Excellent post-mortem of the Signature Bank situation which indeed has been overlooked. Well done.